8. Spouses have one another’s passwords, and parents have total access to children’s devices.

8. Spouses have one another’s passwords, and parents have total access to children’s devices.

8

Naked and Unashamed

8. Spouses have one another’s passwords, and parents have total access to children’s devices.

8. Spouses have one another’s passwords, and parents have total access to children’s devices.

There is nothing in our society that has surrendered more completely, and more catastrophically, to technology’s basic promise, easy everywhere, than sex.

For countless generations, sex was hardly ever easy, and it certainly was not everywhere. It was not easy, above all, because it was intimately connected to the begetting of children, and the arrival of a child is one of the most gloriously complicated events that can befall a human being. As far as possible from being everywhere, sex was meant to be confined to a single lifelong marital relationship, where—as almost any married couple can tell you—sex can be fulfilling and rewarding, but it is by no means always easy.

The one-flesh union of traditional marriage, as it was understood for centuries, united two biologically differentiated creatures who, while both image bearers of God, were almost always invested with profoundly different sexual capacities, desires, and needs. And the lifelong nature of that ideal union meant that marital sex did not just encompass the breathless, hormone-fueled days of early attraction but also long years of middle age and old age—all subject to the vicissitudes of each partner’s health, each one’s waxing and waning desires, and the thousand ups and downs that come with any lifelong relationship. Furthermore, many human beings would spend long seasons of their lives outside such a union, whether because of lack of a suitable partner, a call to priestly or monastic celibacy, or their husband’s or wife’s early death.

The sexual drive is among the most powerful sources of human behavior, so it is no surprise that even in the most traditional environments, the norms of marital sexuality and nonmarital chastity were bent and broken in countless ways. But the powerful social incentives to conform to the underlying norms, along with the ever-present likelihood of conceiving a child from male-female intercourse, meant that while there was probably always plenty of extramarital sex, it would never, ever have been described as easy everywhere.

In the span of one lifetime—my own, which conveniently enough began in 1968, the year that marked the apex of the social and sexual revolutions of the twentieth century—all these norms have been swept away. For most American youth and young adults, thanks to the relentless messaging of popular and mass culture, sex is indeed everywhere. This is true not only in the imaginative world of media but also in their actual experience, in relationships unsupervised by adults or extended family. Especially among young adults, but even among many middle schoolers and high schoolers, the easy-everywhereness of sex is dramatically increased by easy-everywhere access to alcohol, cannabis, or other drugs. They cast a haze of lowered inhibition over the inescapable vulnerability of sex, even for the most jaded and “experienced.”

The norm, now, is for sex to be everywhere, available to everyone at every stage of life and in every configuration of desire, and to be easy—that is, unencumbered by consequences, hang-ups, or commitments. Marriage is now an entirely separate matter; it is not about the sexual union of two profoundly different expressions of human image bearing but fundamentally about a declaration of love by two people that is usually meant to include sexual exclusiveness but is by no means the exclusive domain for sex. Sex itself can and should happen, especially according to the dominant cultural messages, wherever there are willing and consenting participants—two, or more than two, or for that matter just one.

All this has been tremendously assisted by technology. Above all, technology has made contraception affordable, routine, nearly foolproof, and low maintenance. And medical treatments have rendered most sexually transmitted diseases (now simply and casually called “infections”) manageable for most residents of the affluent Western world.

With sex dissociated so completely from the family, it is perhaps not surprising that family itself, so totally the opposite of easy-everywhere life, is being reconfigured. One in three children in the United States live without their biological father in the home.1 And as family becomes less solid and stable, the parental oversight that used to guide and restrain youthful sexuality diminishes. Growing up without one’s biological father, specifically, is related to everything from early onset of puberty, to early initiation of sexual activity, to vulnerability to sexual advances from nonbiologically related household members like stepfathers and half siblings.2 Even those who grow up with both their mother and father are often plunged into the unsupervised environment of college at age eighteen, and on average they will not marry until their late twenties, if they marry at all.3 Adrift in this chaotic and complex environment, young people have to sort out for themselves a vision of what sex is and should be.

And right there to help them acquire and manage a technology-saturated, easy-everywhere view of sex is the ultimate easy-everywhere sexual technology: pornography.

The New Normal

Streaming into our homes and onto our phones—accounting, by the most widely cited estimate, for 30 percent of all internet traffic—pornography provides and portrays a world where sex is easy.4 Sex is widely available in porn. Almost everyone depicted is accessible and eager, and even the truly disturbing forms of porn that depict reluctance or resistance end with a dominating person getting exactly what he or she desires, sometimes through violence. Pornographic sex can be endlessly customized, so that it appeals perfectly to every possible set of desires and “needs.” It purports to have no consequences except pleasure and an appetite for more of the same. It comes with no entanglements and is completely under the user’s control (or so it seems—until porn users find themselves entangled in addiction to porn itself). And it certainly is everywhere—and not just in professionally produced or distributed forms but in a whole set of poses, postures, practices, and assumptions that are replicated in advertising, music videos, and ultimately in everyday behavior by teens and younger children who may not even know, at first, what they are imitating. The most prolific creators of pornography, in the sense of still and moving images designed to arouse, are not professional pornographers but ordinary people, starting in the teenage years. An astonishing 62 percent of teenagers say they have received a nude image on their phone, and 40 percent say they have sent one.5

The porn-saturated culture comes to see sex itself as a kind of technological enterprise—to be assisted with various devices and techniques that ensure satisfaction, remove vulnerability and uncertainty, and require neither wisdom nor courage, just knowledge and desire (and knowledge of one’s own desires). The next frontier in porn will be enhanced by virtual reality and robotics, so that devices substitute entirely for other people, allowing for a perfectly controllable experience of solitary ecstasy.

It is all, of course, a lie. Evidence is piling up that the earlier and the more you use porn, the less you are capable of real intimacy with real partners.6 There is no lasting sexual performance, let alone satisfaction, without the development of wisdom and courage—how could there be for something so core to human existence? There is no technological way to replace becoming the kind of people who know ourselves and know another well enough to truly, deeply give ourselves to them. But as with all addictions, by the time you discover the disappointing reality of pornified sex, you are very often unable to break free on your own. Technology’s promise of shortcuts around the long path of wisdom and courage turns out to be a lie.

The Ubiquity of Porn

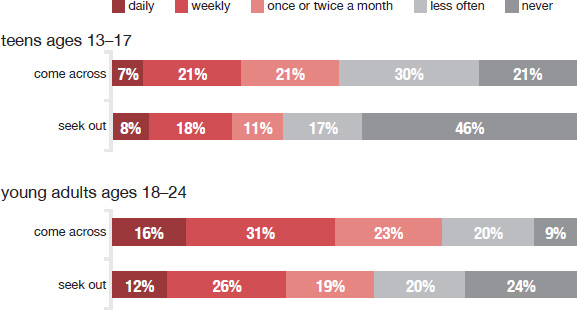

How frequently do you come across or seek out porn?

% among US teens and young adults

n = 813 US teens and young adults ages 13 to 24; July 2015; due to rounding, numbers may not add up to 100

All of us would want to spare our children, our spouses, and ourselves from this plague, but in one sense, none of us can. If you have teenage children, whether boys or girls, it is likely that they have already been exposed to pornography and that they have sought it out. It is not just individuals who become addicted to porn; our whole society has embraced the underlying easy-everywhere view of sex that feeds it. And yet there are both nudges and disciplines we can embrace that will give us a fighting chance of real faithfulness and intimacy—and ultimately, real family. And they begin, not with any direct assault on porn itself, but with everything that we have covered so far in this book.

All addictions feed on, and are strengthened by, emptiness. When our lives are empty of relationships, porn’s relationship-free vision of sex rushes in to fill the void. When our lives are empty of meaning, porn dangles before us a sense of purpose and possibility. When our lives have few deep satisfactions, porn at least promises pleasure and release. Nearly half of teenagers who use porn, according to Barna’s research, say they do so out of boredom—higher than for any other age group (see the chart “Reasons Teens Search for Porn”).

So the best defense against porn, for every member of our family, is a full life—the kind of life that technology cannot provide on its own. This is why the most important things we will do to prevent porn from taking over our own lives and our children’s lives have nothing to do with sex. A home where wisdom and courage come first; where our central spaces are full of satisfying, demanding opportunities for creativity; where we have regular breaks from technology and opportunities for deep rest and refreshment (where devices “sleep” somewhere other than our bedrooms and where both adults and children experience the satisfactions of learning in thick, embodied ways rather than thin, technological ways); where we’ve learned to manage boredom and where even our car trips are occasions for deep and meaningful conversation—this is the kind of home that can equip all of us with an immune system strong enough to resist pornography’s foolishness.

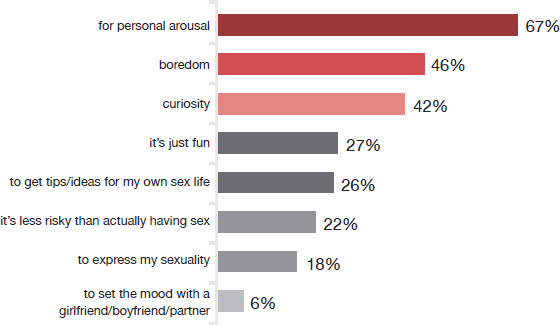

Reasons Teens Search for Porn

Why do you view porn?

Select all that apply.

% among teens ages 13 to 17 who actively seek out porn

n = 543 US teens ages 13 to 17 who actively seek out porn; July 2015

That is part of why this chapter comes toward the end of the book rather than at the beginning, even though almost every parent’s number one concern about technology is the risk of exposing children to pornography and other forms of accelerated sexuality. The truth is that if we build our family’s technological life around trying to keep porn out, we will fail. Pornography saturates our society even if you somehow manage to never click on an “NSFW” (not safe for work) website. When I was a child there was a popular television drama called The Boy in the Plastic Bubble, featuring an impossibly young John Travolta, about a boy suffering from an immune disorder, confined by his parents and doctors to a germ-free plastic enclosure. The drama, of course, centered on his constant quest to escape. The path to health is not encasing our children in some kind of germ-free sterile environment that they will inevitably try to flee; rather, it is having healthy immune systems that equip us to resist and reject things that do not lead to health. Everything up to this point in the book has been about creating that kind of healthy immune system for everyone in our homes—becoming the kind of people who see technology’s shallow pleasures for what they are and set their sights on pursuing something better and deeper, together.

The Naked Truth

That being said, even people who have healthy immune systems do well to put on rubber gloves, if not a hazmat suit, when they deal with especially toxic environments. And there are some things we can do to minimize our exposure to the toxicity of pornography.

The most basic internet equivalent of gloves and safety goggles, of course, is a good filter. Internet technology changes rapidly enough that a book like this isn’t the best guide, and no system will provide foolproof protection, but parents who do not implement powerful filters on the data streaming into their home are foolish about both their children’s vulnerability and their own. (Our home internet is filtered by the OpenDNS service, which constantly updates and blocks sources of sexually explicit content as well as other objectionable material.) We also waited until our children were nearly at the end of high school to provide them phones with independent data plans that could circumvent our home internet. It is astonishing how many parents blithely give young children smartphones that allow absolutely unfettered access to whatever the internet (and links from their friends) may serve up.

The truth, though, is that any automatic system for blocking unwanted content is a leaky sieve at best (and no match for a savvy and determined teenager). We need something more powerful: accountability, transparency, and visibility, all in the context of relationship.

So my friend Matt, who has four middle- and high-school-age sons, has told each one, “I’m your dad. Until you are grown, it’s my job to know more about what’s going on in your life—and therefore on your phone—than anyone else.” His sons know that he can, and will, look over their shoulder at any moment, and that he can, and will, and does, pick up their phone without needing to ask and browse through their messages and apps and history.

To many parents, and to nearly every American teenager, this will seem like an impossible invasion of “privacy.” But Matt’s sons have plenty of privacy. He doesn’t barge into their bedrooms, and he can’t, and wouldn’t want to, police their secret thoughts or their conversations with friends at school. He makes a great deal of room for his sons to come to their own conclusions about their convictions and to develop, or not, their inner spiritual and emotional lives. What Matt understands, though, is that if mature adults struggle to handle the pipeline of temptation, titillation, and distraction that comes with 24/7 access to the internet, there is no way still-developing teenagers can handle it. His oversight is strictest where the technology is most powerful and potentially out of control.

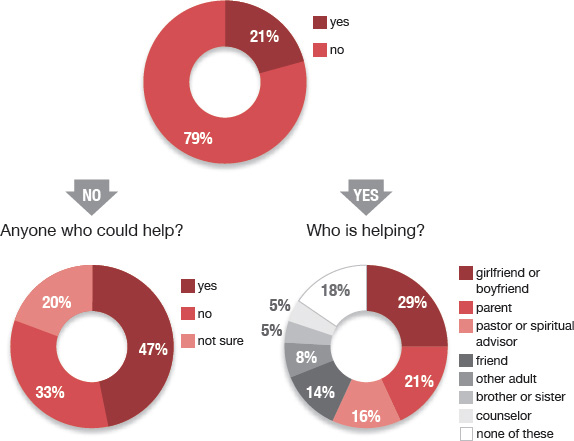

The Loneliness of Trying to Quit Porn

Do you have anyone in your life who is helping you avoid pornography?

% among US teens and young adults who would like to stop using porn

n = 351 US teens and young adults who say they want to stop using porn; July 2015

And when you spend time with Matt, his wife, Kim, and their boys—and with his sons’ friends, who flock to him because of his infectious sense of humor, his relentless respect for kids, his willingness to ask and answer any question, his warmth as well as his strictness, and perhaps above all his endless humility and openness about his own struggles and failures from his high school years to the present—you realize he’s the kind of dad every child is dying to know.

So the tech-wise family will make a simple commitment to one another: no technological secrets, and no place to hide them. If your family has a shared computer, arrange it so the screen faces the rest of the room and others who may wander in. Until children reach adulthood, parents should have total access to their children’s devices. I’m well aware this won’t stop teenagers from deleting text messages the moment they arrive, relying on self-destructing apps like Snapchat, and engaging in countless other subterfuges—if they choose. But when they do so, they will know they are violating a family practice of openness to and with one another; they will be making choices, even poor ones, within a moral framework rather than simply blundering their way through adolescence without any guidance or boundaries.

Likewise, spouses should have one another’s passwords and should cultivate the complete freedom to ask one another anything at any time. Even more than parents and children, spouses are bound for life as “one flesh.” This level of access is not a matter of managing, let alone preventing, failure and sin. It has a simpler and deeper purpose: to keep us deeply connected to one another in ways that make failure and sin both less attractive and less damaging to our souls and our relationship. All sin begins with separation—hiding from our fellow human beings and our Creator, even if, at first, we simply hide in the “privacy” of our own thoughts, fears, and fantasies. Anything that short-circuits our separation, that reinforces our connection to one another and our need for one another, also cuts off the energy supply for cherishing and cultivating patterns of sin.

Will we avoid the technological maelstrom of easy-everywhere pseudosex (since that is all it is, nothing like the real, far more complex and beautiful, God-given thing) by keeping our filters up, sharing our passwords, and monitoring our children’s devices? Hardly, any more than residents of the most polluted cities in the world can purchase enough air filters to avoid ever breathing in noxious fumes and dangerously tiny particles. But we can limit the damage it does to ourselves, our marriages, and our children. To use an older and hilariously apt metaphor attributed to Martin Luther, we can’t stop the birds from flying over our head, but we can stop them from building a nest in our hair.

We rob the easy-everywhere world of its power to seduce us not so much by the rules we put in place as by the dependence on one another we cultivate—depending on one another to help us be our best selves, growing in wisdom and courage and serving one another, in a world that wants to make us into shallow slaves of the self. Among the most heartening findings in the largely horrifying research on pornography use and addiction is that even people who plunge into addiction can emerge from that shallow madness, retrain and rewire their brains, and rediscover real intimacy.7

It takes time and trust, but it can be done. Lifting one another out of the tombs of addiction, slowly unwrapping the grave clothes, and calling one another back to life—as well as nudging and urging one another toward the life that really is life—that is what family is for.

Crouch Family

Reality Check

It’s painful to admit that, beyond the basic filtering of our home internet service, we haven’t had the same level of courage and involvement that our friends Matt and Kim have in their children’s lives. We’ve talked many times with our kids about the distortions of our pseudosex-obsessed world—enough, we hope, to give them healthy immune systems for all they will encounter and have already encountered. But there is probably more we don’t know than is really healthy about our family’s exposure to porn.

And I have had to confess to Catherine my own failures. I will never forget coming home from a dinner party at one of the residence halls of Harvard, where we lived and worked at the time, knowing that I had to tell Catherine the truth about my enmeshment in pornography. Telling the searing truth about my foolishness was a brutal contrast to the urbane conversation earlier in the evening. But as painful as it was, it was one of the most enduringly fruitful moments of my life. Her dismay and her forgiveness were the two essential ingredients in freeing me from my enslavement to porn’s unreality—probably because it is only the combination of dismay and forgiveness that keeps any of us sane.