9. We learn to sing together, rather than letting recorded and amplified music take over our lives and worship.

9. We learn to sing together, rather than letting recorded and amplified music take over our lives and worship.

9

Why Singing Matters

9. We learn to sing together, rather than letting recorded and amplified music take over our lives and worship.

9. We learn to sing together, rather than letting recorded and amplified music take over our lives and worship.

Once upon a time, we knew how to sing.

It’s true in American life generally. When I was a boy, the national anthem was sung at baseball games and patriotic events by the entire assembled crowd. It wasn’t sung well, necessarily—that high note on “rocket’s red glare” was often pretty disheveled—but it was at least attempted.

Now, I can’t remember the last time I was in a public place where the whole crowd had the job of singing the national anthem. Instead, we’ve assigned that job to experts, professional or aspiring singers who sing on our behalf (sometimes badly, but still boldly). The rest of us simply do what we are going to do for the rest of the game: watch, listen, and enjoy as someone else demonstrates skill and courage.

This is also true in American Christianity. We once knew how to sing. Many great renewal movements within Christianity have been linked with a renewal of communal singing. (Even some of the not-so-great renewal movements, the ones that ended up in heretical dead ends like the Shakers, were still noted for their magnificent songs.) The founder of Methodism, John Wesley, began to question and deepen his own faith when he heard German Moravians singing during a terrible storm on board a ship bound for the United States.1

There are still places in American life where you can hear amazing singing welling up from an entire gathered community, not just from a professional chorus or choir. Almost all of them are in church. But even in church, those places and moments are fewer and fewer. In my travels around the United States, I’m in many different kinds of churches and worship environments. I’ve also studied singing and worked as a professional musician, not least in historically black churches that have kept gospel music and the tradition of Negro spirituals alive, and I know something of what human beings are capable of doing with their voices. In most places I go, the singing is a faint echo of what would be possible from the people assembled if they were asked, let alone trained, to sing.

Not that our churches are without music. Our worship bands are more technically proficient than ever, and louder than ever. The people holding microphones are singing, often expertly and almost always passionately. It’s just the rest of us who, like the crowd at a ballgame, are mostly swaying along, maybe echoing a few of the phrases or words.

At the root of the disappearance of shared singing in public life and our churches is one of the most profound changes in the history of human beings, who have made music, as far as we can tell, from the very beginning. Up until about one hundred years ago, there was only one meaning to the phrase “play music.” It meant that someone had to take up an instrument, having developed at least some skill, and make music, in person, in real time. They were not always expert musicians—the diaries and novels of the nineteenth century are full of rueful comments about how poorly some cousin played the piano in the family parlor. But there was only one way for music to be “played”—and that was for someone to play it.

Today, to “play music” can mean something totally different. The glorious technological magic of recorded music is now absolutely ubiquitous around the world. With a few taps or clicks I can call up a lifetime’s worth of music over the internet and play it through speakers or headphones—an astonishing abundance that is truly easy and everywhere. And in one sense, the quality of the music I can summon with my devices is far higher than anything ever heard in the days when playing music meant an actual embodied activity; indeed, many professional recordings, thanks to editing and engineering, are far better than the original performance ever was.

Like so much of technology, there is no way to deny that this easy-everywhere abundance of music is a gift. And it has also caused us to forget and neglect what every other generation of human beings, in every culture, remembered and cultivated: the ability to make music on our own. Sitting in the living room or on the porch singing together, or listening to one another play instruments, was once a normal part of many American families’ lives together. Today, I dare say, for the vast majority of American families it would seem impossibly corny and embarrassing. We can consume more music than they ever did; we create less music than they ever could have imagined.

If this just affected our leisure lives, it would be sad but perhaps not tragic. At least no one has to put up with artless cousins playing the piano in the evening anymore. But the reorientation of our musical lives around consumption is robbing us of something deeper; it is robbing us of a fundamental form of worship.

Worship, Wisdom, and Courage

I said at the beginning of the book that the real purpose of family is to develop wisdom and courage—to give us a deep understanding of the world and an ability to act faithfully in that world. But we cannot develop wisdom and courage only inside the walls of our home. Every family that cares about wisdom and courage needs to be part of a community larger than itself—a community that takes us deeper in our understanding of the world’s beauty and brokenness, and that calls us to greater character than we would ever muster on our own.

The Christian conviction is that the best such community is the church: the true family of which all of our smaller families are merely partial signs. And the most distinctive thing the church does—the thing that most directly develops wisdom and courage in us, from childhood through old age—is call us to worship the God who made us in his image.

Worship is the path to true wisdom. “The fool says in his heart, ‘There is no God’” (Ps. 14:1 NIV). And since human beings cannot actually live without some sort of god—some sort of ultimate reality—the fool makes something else god, often himself. But this leads to a shallow and dangerous view of the world. Worship brings us to the real truth about the world, its original intention and its ultimate meaning, and our responsibility in it. And this is not just a matter of merely knowing that truth; we must respond with our whole being to that truth and the One who is the source of that truth.

If you want to be wise, then, the most important thing you can learn to do is worship.

Worship is also the path to real courage. This might not be true if it were a merely informational activity, like taking a weekly class on the Bible. Just because you know something is true doesn’t mean you have the courage to act on it. But worship is actually more like a form of training—practicing, week after week, ideally in the presence of others who are further along in faith than we are, the exertion of our heart, mind, soul, and strength in the direction of giving glory to God. And Christians believe that God actually responds and moves in the midst of our worship: when we gather ourselves to offer him praise, he in turn dwells with us. At its best, worship transforms us, making us people capable of things we could never work up the capacity or courage for on our own: the ability to sacrifice, to love, to repent, to forgive, and to hope.

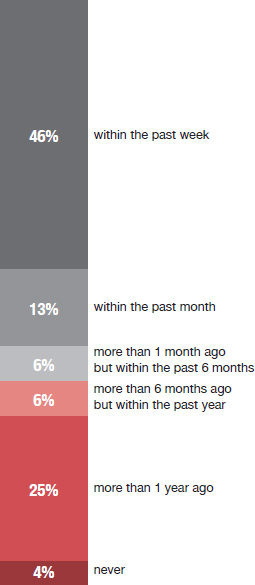

Churchgoing among American Families

When was the last time you attended a church service other than for a holiday, wedding, or funeral?

n = 1,021 US parents of children ages 4 to 17

Worship reminds us of the shape of true life. One of the biggest threats to wisdom and virtue in a technological age is that we can so easily settle for something less than the best. What kind of life do we want for our children? The easy, safe, protected life afforded by modern technology—the kind of happiness that leisure and affluence can buy? Worship calls us out of the small pleasures of an easy-everywhere world to the real joy and burden of bearing the image of God in a world where nothing is easy, everything is broken, and yet redemption is possible. Think about the most beloved hymn in the English-speaking world, “Amazing Grace,” and how deeply it embodies these themes—so much so that the rock star Bono and the American president Barack Obama have both led audiences in singing it. At the really crucial moments of greatest beauty and tragedy, only music that flows from the heart of the gospel is really enough.

And so worship is the most important thing a family can do. It is the most important thing to teach our children and the most important thing to rehearse throughout our lives. The Jewish people have known this ever since they were commissioned by God to be his chosen people. The central words of Israel’s worship life are directly connected to family life:

Hear, O Israel: The LORD is our God, the LORD alone. You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might. Keep these words that I am commanding you today in your heart. Recite them to your children and talk about them when you are at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you rise. Bind them as a sign on your hand, fix them as an emblem on your forehead, and write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates. (Deut. 6:4–9)

Even today, observant Jewish families place these very words, written by hand on a small scroll of parchment, in a small case on the doorposts of their homes. The home is the place where worship of the true God starts: the place where we remember and recite God’s Word, and where we learn to respond to God with our heart, soul, strength, and—as Jesus added when he called this the greatest commandment—with our mind as well.

And while it doesn’t say so in this text, I believe the very best way to learn to worship, at home or in our churches, is to sing.

Worship is more than singing, of course. But there is something about singing that is fundamental to Jewish and Christian worship—starting with the Psalms, continuing with the hymns that grew out of the early church and the renewal and revival movements of subsequent centuries, finding new expression in the chants of Christian slaves in the American South, and abounding even today in a profusion of “worship music.”

Simply, singing may be the one human activity that most perfectly combines heart, mind, soul, and strength. Almost everything else we do requires at least one of these fundamental human faculties: the heart, the seat of the emotion and the will; the mind, with which we explore and explain the world; the soul, the heart of human dignity and personhood; and strength, our bodies’ ability to bring about change in the world. But singing (and maybe only singing) combines them all. When we sing in worship, our minds are engaged with the text and what it says about us and God, our hearts are moved and express a range of emotions, our bodily strength is required, and—if we sing with “soul”—we reach down into the depths of our beings to do justice to the joy and heartbreak of human life.

To sing well—not in the sense of singing in perfect tune or like a professional, but in this sense of bringing heart, mind, soul, and strength to our singing—is to touch the deepest truths about the world. It is to know wisdom. And it’s also to develop the courage and character to declare that God is this good, that we are this in need of him, that we are this thankful, that we are this committed to be part of his story.

In too many of our churches, however, we have settled for a technological substitute for worship: amplification, which allows a few experts to do the worshiping on our behalf while we offer far too little of our own heart, soul, mind, and strength. As a working musician I do appreciate what amplification makes possible. In many ways, amplification is to sound what a cathedral is to space, creating a sense of wonder and transcendence out of ordinary stuff. The best amplification actually undergirds and calls forth great singing from the whole assembly.

But too often, instead, amplified voices and instruments let the rest of us off the hook; overwhelm our voices, which could be so powerful but instead sound by comparison so feeble; and subtly teach us that those of us without microphones are just consumers of worship rather than active offerers of it.

Rehearsing for Glory

It is absolutely possible to learn to really sing. You may or may not be able to learn to sing on pitch, but you can learn to sing with heart, mind, soul, and strength. The best time to begin to learn is in childhood, when our brains are primed for learning, our neuromuscular system is most able to be trained to connect mind with strength, and we are fearlessly willing to try something new. And of all the components of well-led worship, singing is the one that is most immediately accessible and engaging to children (listening to sermons takes a while longer!).

So the tech-wise family will do everything in their power to involve their children from the earliest possible age in expressions of church that model this kind of worship—not just the pleasant ditties of Sunday school or “children’s church” but the full-throated praise that can come from people of every generation gathered in the presence of God. Maybe that isn’t the Sunday-to-Sunday reality where you worship (it’s only sometimes so in our own church), but it’s worth exposing our children to the communities and places that have kept alive the powerful tradition of Christian song.

And as much as possible, we’ll sing at home, when friends and family gather, as we clean up the kitchen and fold the laundry, as we celebrate holidays like Christmas and Easter, when we get up in the morning and when we lullaby ourselves to sleep. Our singing will be nothing like the auto-tuned, technologically massaged pop music that provides the bland sound track for the consumer life; it will be the sort of singing you only can do at home, where you are fully known and fully able to be yourself. And it will be a rehearsal for the end of the whole story, when all speech will be song and the whole cosmos will be filled with worship.

On January 12, 2010, a massive and devastating earthquake struck just outside Port-au-Prince, the capital city of Haiti. Countless buildings in the city collapsed and over a hundred thousand lives were lost. The already shaky electric power grid was effectively destroyed, along with every other form of infrastructure. That night, with aftershocks rolling through the ground, almost all the residents of the city and the surrounding countryside stayed outside, torn with grief and fear. The residents of the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere had little access to the easy-everywhere life of technology even before the earthquake, and now, with their world in ruins, they had none.

And they sang. When you don’t have technology, you still have song. When you’ve lost everything, in fact, you still have song.2

All over the hills of Haiti those first terrible nights, under the starlit sky, the voices of the people of Haiti rose up in grief and lament, in prayer and hope.

They had something we have almost lost—and they still have it, as anyone who has visited a Haitian church or family knows. We can have it in our homes, and in our churches too, if we choose not to let technology do the singing for us.

Crouch Family

Reality Check

There are many things we’ve done poorly, belatedly, or distractedly in our family, but one thing I am most grateful we have done intentionally is sing together. As with many of our best efforts at intentional life, we have done best at this one during certain seasons of the year—especially Advent and Christmas, when we take advantage of the almost inexhaustible supply of magnificently singable Christmas carols.

And we are grateful that our church keeps the amplification to a reasonable level. In recent years we’ve been attending a smaller service in a chapel that was the original church building, built one hundred years ago and designed for singing. The service is sparsely attended and formal in a way that young people are supposed to find boring. But in fact our teenagers love it, partly because everything depends on the congregation’s singing. Somehow, in that small service, where some members of the congregation are too old to sing with full voice, our kids can grasp more easily that they matter to the life of the church—that worship won’t happen unless all the generations show up with their heart, mind, soul, and strength.