Real estate is different than all other forms of investing in several ways: tax benefits, generation of income to pay for mortgages, and more than anything else, the fact that cash flow is more crucial than profits. While this point was made in the first edition of this book a decade ago, it is as true today as ever. In 2008 and 2009, it looked like real estate was done as a viable investment, but this has been predicted many times in the past. The predictions were always wrong.

Today, real estate looks better than ever for investors. Home ownership rates are way down, but rental rates are significantly higher than in the past. For investors, this means that investment property is today more popular than ever before, based on cash flow as well as profit potential. The true meaning of value in real estate begins with profitability, but ultimately it is determined by cash flow.

All investments are judged on the basis of their current and future market value. In the case of real estate, the historical rise in the market value of properties has been consistent and has served as the base for many long-term financial plans. Many people, whether they are investing only in their own homes or expanding into a portfolio of rental properties, have discovered the potential for profits through real estate.

All forms of investing should be based on study and analysis. Real estate properties vary greatly in cost as well as in quality, location, and income potential. A smart place to begin the search for real estate investments is to identify some of the common myths about this market. These myths include the following:

1.Real estate values always go up. Markets always move in cycles. Therefore, every market, including the real estate market, will exhibit periods of strong growth and periods of stagnation and even declines in market values. While these cyclical changes may be temporary, they are part of the investing process.

2.Profit over the long term is the most important criterion. While profits are important to all investors, most people who put their money in real estate cover the majority of the purchase price through financing. Because investors have to generate enough rental income to cover their mortgage payments (along with property taxes, insurance, utilities, and repairs), profits are only one of the measures by which the value of an investment is judged. Of far more immediate concern is the cash flow that you can gain from that investment. As long as rents are high enough to cover all of your expenses and payments, cash flow is positive. But if rents stop or aren’t high enough to provide that coverage, your investment plan could be in trouble. This is where careful planning and analysis of risks is so important.

3.Tax benefits are so good that it’s always smart to carry a mortgage. A common belief is that a mortgage, even one with a high interest rate, is beneficial as long as rental income is higher than the mortgage payments. The argument may be made that interest on the mortgage payment is deductible as an investment expense, so it does not make sense to pay down that mortgage or to get a lower balance initially. This is false. It is always better to reduce your payments and expenses; you will always end up with a stronger cash position with a smaller mortgage and lower payments.

4.You can’t lose with real estate. It would be more accurate to say that the chances of losses on any investment are drastically reduced when you study the market beforehand. It is possible to lose money on any investment, but that invariably occurs because the real risks were not properly evaluated ahead of time. Real estate investors benefit from the historically strong market value growth in real estate, unique tax advantages for investors, cash flow potential from well-selected properties and well-screened tenants, and intelligent analysis in the selection of investment properties. In spite of advertising to the contrary, success in any form of investing is rarely easy or simple. It can be made so with research, which gives you an advantage over most investors.

The two factors determining real estate value are location and timing. When you begin to study the market, you start out with a large field. Just as a stock market investor starts with a potential investment field consisting of thousands of stocks, real estate investors also face a large number of possibilities and need to narrow down their choices.

Location and timing are concepts that are broadly understood by investors. In the stock market, you have market sectors, size of companies, capital strength, and competitive factors; these are the “locational” aspects of picking stocks. In real estate, location means the specific property and its immediate neighborhood, and also the city or town and larger region where the property is located.

With all investments, timing is everything. If you invest money when prices have peaked, your timing is poor; but the tendency among investors is to have the most enthusiasm and confidence at exactly those moments. If you invest money when prices are depressed, your timing might be good (only time will tell). But the tendency among investors is to be cautious and uncertain when prices have fallen. So the old advice to buy low and sell high applies to all markets, including the real estate market.

You face some artificial indicators when you look at real estate valuation. In a generally strong market, there may be a tendency to believe that all real estate is going to appreciate and that it is impossible to go wrong. Of course, you may see the same false euphoria in the stock market; but in real estate, regional trends may support this belief. Because real estate does not trade on an open exchange like stocks, it is difficult to spot short-term trends or to quantify them, and it is even more difficult to narrow down the location of a sensible real estate purchase.

These artificial indicators can mislead you if, in the search for valid data about the local market, you do not distinguish between broad and narrow forms of analysis. Mistakes in this area are of three types:

1.Reviewing regional or national data on real estate trends. The information about real estate that is easiest to find comes from sources like the National Association of Realtors (www.nar.realtor.com) or the U.S. Census Bureau (www.census.gov). Also check Zillow (www.zillow.com), Realtor.com (www.realtor.com), and Multiple Listing Service (www.mls.com). All of these sources are extremely valuable for all real estate investors, but the statistical and demographic real estate trends reported on these sites are regional and national. Real estate investors need to get down to the market supply and demand factors right in town. Average pricing trends for a section of the country or the entire nation are not of any use in timing a decision to buy investment real estate. All trends are local.

2.Application of irrelevant data to the specific market. If you are interested in buying rental property, you should also make sure that you study the applicable data. For example, if you want to purchase a fourplex and rent out its units, the decision should be made on the basis of prices, rental rates, and demand trends for similar properties. Local demand trends for single-family houses, raw land, or commercial property are not useful. While local trends for different types of real estate do tend to move in the same direction, there are no guarantees. Local economic forces, such as growth in jobs or an active tourist industry, may affect commercial property values, and increased prices of raw land may reflect a growing retirement demographic. At the same time, rental property may be lagging for a variety of reasons.

3.Misreading one form of supply and demand when your concern should be for another. The natural tendency of investors is to look to real estate because market values are rising. Most begin with the purchase of a single-family home as a rental. Some people move into this market when they decide to buy a larger home; instead of selling, they convert their present home to a rental with the idea that the tenants will “pay the mortgage” through rents. However, a strong demand for owner-occupied housing might not support a strong demand for rentals. It is possible that owner-occupied trends may be very strong, while rental demand is soft. These two markets are entirely separate. Factors influencing rental demand, even when single-family housing demand is strong, would include overbuilt apartment units. In that situation, housing prices may be rising at far above the national rate of inflation, while vacancy rates are high and market demand for rentals is soft. The supply and demand cycles for home ownership and for rentals are distinct and separate.

The question of where and when to buy is a strictly local one. It is not enough to study regional trends; you need to look at the trends in your city and, more specifically, in a particular neighborhood. Even in cities with only a few thousand residents, markets may differ vastly based on specific location. Before committing to real estate investments, it is essential to research the attributes of a neighborhood and how prices are trending, the types of rental demand and market prices for properties on a neighborhood-to-neighborhood comparative basis, and what factors influence those values (access to transportation, shopping, jobs, and schools, for example).

Analyzing real estate values requires comparative analysis, and many useful calculations certainly help. But as a starting point, you need to know the market firsthand. This is why a majority of first-time real estate investors tend to buy properties close to where they live. There are practical reasons for this, of course, but it simply makes sense to invest on familiar ground, literally speaking. You are most likely to understand the real estate trends within a few blocks of your own home and far less likely to understand the forces at work somewhere else, even in a city or town only a few miles away.

It may be fair to observe that there are two separate real estate cycles. The first is the theoretical or academic version that is studied in economics graduate classes; the second is the real cycle that is witnessed (or suffered) by real estate investors, builders, and developers. The largest cycle hit bottom in 2008 and has been working its way back up ever since. As of 2017, the market looks strong and is heading back to its high cycle level. This is the best condition for getting into the market.

Why are these different? The mathematical models of cyclical forces are useful to students whose exposure to economic forces is limited or nonexistent. Most students in economics graduate classes have never owned real estate or put money at risk in any other meaningful way, so, appropriately, their comprehension of real estate cycles will be based on theory rather than on practical experience. But experience provides investors with a far more pragmatic understanding of how money is made or lost. You see this in the stock market. Thousands of American investors jumped on the dot-com fad and bought shares of Internet stocks, many of which had never reported a profit. When the fad ended and many of those companies went out of business, investors lost money. For many people, this was the first time they had invested money. Having never had a loss before, it came as a cruel shock—but this is the reality.

In real estate, the same disparity is going to be found in first-time investors. While the market and its attributes are quite different from the stock market’s tech-stock fad, the same caution applies. The theoretical real estate cycle is not going to dictate how the real-world cycle operates, in terms of how long a cycle lasts or how far the cycle swings. Real cycles are characterized by short-term changes: misleading indicators, stagnation, and random movement. It is a mistake to attempt to time purchases through observation of current cycles. These cycles—varying degrees of supply and demand—are constantly shifting back and forth, and it is difficult to anticipate cyclical movements accurately. Both supply and demand contain a vast number of market components that can be understood best in a broader view, using historical information to follow trends and looking at moving averages. It is rarely possible to gain an absolutely clear view of current market conditions. It makes more sense to make investment decisions based on the fundamental strengths or weaknesses of the market (price trends in the immediate neighborhood, comparable sales prices of property, strength of rental demand, and so on). You should remember Mr. Dumby’s observation in Oscar Wilde’s play Lady Windermere’s Fan, “Experience is the name everyone gives to their mistakes.”

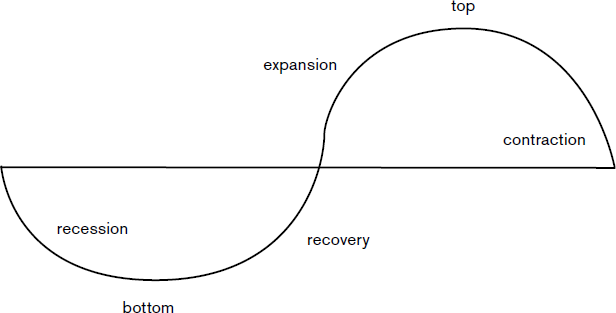

To demonstrate how the difference between theory and reality play out, review the illustration of the real estate cycle shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: The Supply and Demand Cycle

The well-known economic identification points are shown in a falling and then a rising trend: recession, bottom, recovery, then expansion, top, and contraction. This model uses a base value that begins and ends in the same place. However, if prices are trending up over a period of time, it is more likely that the base value will rise as well. In other words, while these cyclical phases will occur, the beginning and ending points will not be identical. This is illustrated in Figure 1.2.

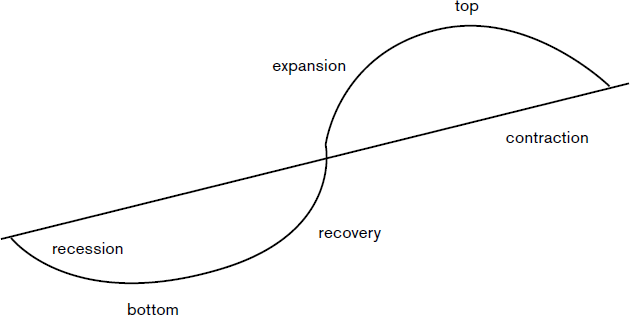

Figure 1.2: The Supply and Demand Cycle with Moving Base Values

Note that the overall value of real estate in this more realistic cyclical pattern rises over time, even while the forces of supply and demand interact and change. Stock market analysis may be realistically based on a set price level, and observers may experience times when prices are higher or lower than that level. Or price trends for stocks may also rise. In any market, the tendency for long-term price averages to evolve is a fair assumption, and the supply and demand cycle acts within that longer-term value trend.

Another important variation to note is the timing of a cycle. In the illustrations, the recessions and expansions are identical in length, indicating that these forces of change are somehow predictable. In practice, however, real estate cycles may be completed very rapidly (in a year or less as a form of minicyclical change), or they may evolve over many years. In addition, the recession and expansion phases are not necessarily equal in length. Recession may occur very gradually and expansion in a far shorter period, or vice versa. The aspect of cyclical analysis that is the most interesting, in fact, is the uncertainty. When you study cyclical patterns, you even out the timing and the false starts or stops along the way.

Cycles are best understood when they are analyzed broadly and with the use of averages. In practice, however, supply and demand changes do not act in average ways. The actual movement of the supply and demand cycle is more often far more chaotic and random.

The study of economic supply and demand cycles helps you to appreciate the interactions between buyers (demand) and sellers (supply). However, the analysis of real estate has to be based on local trends, not on regional or national cycles. When you hear statistics on housing starts, population ownership levels in real estate, or average prices of single-family homes, you need to put that information in perspective. National and regional trends are interesting, but they do not reveal what is happening in town.

Local values and trends are far more important to you as an individual investor. The starting point in any analysis should be identifying the market area where you expect to operate. The market area for real estate is not all real estate, nor is it a specific type of real estate, such as a single-family home. The applicable market area is a specific type of property located in a very specific locale with a price that is within a narrow range. An integral part of your market research is gaining an understanding of local rental demand levels and market rents.

On the individual property level, you start by looking at the land, the condition of the building, and the surrounding neighborhood. The age of the property and the condition of surrounding properties are revealing because they provide an idea of whether current owners have performed ongoing maintenance, both for the property for sale and for the entire area. Neighborhoods tend to go through transitions, so condition may be a key indicator in identifying the best time to buy in an area. For example, one area may have many homes owned by older retired people whose children have grown and moved; as these older residents pass away, the homes are purchased by a new generation of first-time home buyers. (Many first-time buyers purchase older properties because they are more affordable and later trade up to newer, more recently constructed homes; while this is a generalization, it is especially true when newer homes are significantly more expensive than older stock.) In this situation, older homes may be far out of date in terms of heating, electrical, and plumbing systems; roofs and paint; and the yard. So as new owners buy these homes, a positive transition of upgrades, renovations, and improvements begins to occur. This is a positive change because as older homes are brought up to date, they also tend to increase in value. Buying homes in neighborhoods that are in the early stages of positive transition is smart timing.

A negative transition occurs when owners begin moving away to other towns or neighborhoods, often because of undesirable changes. These include increasing crime, added noise resulting from new freeways nearby, or high-impact zoning changes close to the area. For example, when a state decides to run a new freeway through an existing town, it may cut an older neighborhood in half, so that one side becomes isolated from the other. This changes the character of both sides and may also lead to a decline in the market value of housing, a trend exacerbated by the noise resulting from a new freeway. When neighborhoods are going through a negative transition, you may find abandoned homes or empty lots because there is no financial incentive to build in the area, and it may be equally difficult to find suitable tenants. Crime may increase as well as people moving out to escape ever-growing problems. Property values decline in such areas, so you may find “bargain” prices as well as good financing. However, because of the trends that are under way, it is not sensible to buy properties in these areas. It is likely that property values will continue to decline, possibly over many years.

The transitional test is a good starting point in comparing valuation. To help identify the many specific areas that collectively define the direction a transition is taking, check Table 1.1.

While the apparent transition for a single property may not tell the whole story, comparing the trends in several neighborhoods and among a number of properties will help in making distinctions. The selection of a property should be based on a combination of factors adding up to good value for the money: market value potential, good price and financing, safe neighborhood, and more. If you will be using the property as a rental, it also makes sense to check local market rental rates. The condition of the neighborhood determines (1) the market rate for rents, (2) the occupancy level you can reasonably expect to see, and (3) the kind of tenants who will apply.

Table 1.1: Neighborhood Transitions

POSITIVE TRANSITION |

NEGATIVE TRANSITION |

Crime |

Crime |

Local statistics are promising. |

Local statistics are negative or unavailable. |

The area is clean and well maintained. |

There are empty lots, graffiti, and boarded-up homes. |

Police reports show a decline in crime. |

Police report rising crime, notably in felony classifications. |

Employment |

Employment |

Job growth is strong. |

Jobs are being lost. |

Unemployment is steady or falling. |

Unemployment is rising. |

Hazards |

Hazards |

Hazardous conditions are fixed quickly. |

Hazards are left or take a long time to remove. |

Zoning rules are enforced. |

A lot of mixed zoning is evident. |

Health Care |

Health Care |

The area is noted for excellent facilities. |

There is a shortage of adequate care facilities. |

Hospitals and clinics are conveniently located. |

Residents travel elsewhere for health care services. |

Citizens have voted for hospitals and emergency medical services. |

Hospitals and emergency systems are overloaded. |

Home Maintenance Levels |

Home Maintenance Levels |

Good care is taken by area homeowners. |

Homes and gardens are poorly maintained. |

Many homes are upgraded and renovated. |

Properties are outdated and maintenance is deferred. |

Few “For sale” or “For rent” signs are seen. |

Many homes are for sale or for rent. |

Noise |

Noise |

No traffic or other noise is evident. |

Local noise levels are high and noticeable. |

The area is generally quiet. |

Facilities (such as airports) are nearby. |

Parking |

Parking |

There is plenty of street parking available. |

Streets are too narrow; people park on lawns or gravel. |

Most homes have driveways. |

Few driveways are available. |

Traffic |

|

Traffic levels are low. |

Traffic is constant. |

People follow the speed limit. |

People speed without regard for safety. |

Traffic control is adequate given volume. |

Traffic piles up at stop signs and lights. |

Planning |

Planning |

Neighborhoods are well planned. |

Street patterns are haphazard. |

Yard and lot areas are clean. |

Ordinances regarding unsightly yards are not enforced. |

Types of property are consistent within areas. |

Many trailers, campers, and empty lots are evident. |

Buffer zones between zoning are maintained. |

Dissimilar zones seem to merge into one another. |

Residential lots are uniformly sized. |

Lot sizes vary considerably. |

Recreation |

Recreation |

Many desirable parks and playgrounds are seen. |

Few recreational areas are found. |

Existing recreational areas are well kept. |

Existing recreational areas are poorly kept. |

Statistics on Sales |

Statistics on Sales |

Home sales levels are consistent. |

Many homes are for sale. |

New homes and subdivisions are being built. |

No new construction is under way. |

Homes remain on the market only briefly. |

Homes remain for sale for long periods. |

Public Amenities |

Public Amenities |

There are schools and shops nearby. |

Schools and shops are a distance away. |

Malls are well maintained. |

Malls are in disrepair and many shops are empty. |

The downtown area is clean and robust. |

Downtown is virtually abandoned. |

Public transportation is efficient. |

Public transportation is slow and expensive. |

Checking the property and the neighborhood is a smart test, but it is only the beginning. Once you find one or more properties that seem to be well priced, the next step is to evaluate the overall local market. What is the current state of supply and demand? Is the market currently a buyer’s market or a seller’s market? What trends are going on now, and what should you expect in the near future?

If you ask a real estate agent these questions, you may not get a completely accurate answer. As a general observation, agents (whose compensation is commission based) tend to tell buyers that this is the best time to buy, and to tell sellers that this is the best time to sell. They are motivated to generate sales, and that requires that both sides come to the table. It would be rare for a real estate agent to tell a seller not to put a property on the market, or to discourage a potential buyer from looking at properties in the current market conditions.

To perform your own research on local market conditions, you need to dig a bit deeper and to study the trends on your own. Good local sources for statistics, especially in the housing market, are the area’s Multiple Listing Service (www.mls.com), Movoto (www.movoto.com/market-trends), or the National Association of Realtors (www.nar.realtor/research-and-statistics). Local Multiple Listing Service offices publish periodic summaries of homes for sale, with pictures and details, and summaries of recent statistical trends. This is where you find information that reveals the supply and demand conditions in today’s local market.

The first step is to identify the inventory of homes on the market and then calculate the amount of supply that inventory represents. Inventory is simply the number of properties of each type that are for sale. For example, if you are interested in investing in single-family houses, you would not want to include commercial properties, apartment houses, or raw land; you would want to count only the inventory of houses currently for sale. Next, determine the average number of properties (in your category) that are sold each month. Divide the inventory (number of homes available) by the average number of closings that have occurred each month to find the number of months of housing inventory currently on the market.

•Formula: Months of Property Inventory on the Market

I ÷ S = M

where:

I |

= total inventory of properties currently available |

S |

= average sales per month |

M |

= months of inventory currently available |

•Excel Program: Months of Property Inventory on the Mark

A1: |

total inventory of properties |

B1: |

average sales per month |

C1: |

=SUM(A1/B1) |

Like most forms of statistical analysis, the current number of months’ inventory reveals only a part of the picture. Market conditions are clearly different in an area that has only two months’ inventory versus another area with twelve months’ inventory. However, you also want to track the trend in inventory. Is it growing or shrinking? Are there predictable seasonal considerations to keep in mind, and if so, what effect is predictable at each time of the year? Following the trend reveals the direction of the supply and demand cycle.

Two additional indicators found in Multiple Listing Service sales statistics are the spread between asked and sale prices and the amount of time between the original listing date and the closing date. By tracking the trends in these two important indicators, you can judge the strength or weakness of the market and assess both supply and demand conditions (as well as the direction and speed of the real estate cycle).

Spread is calculated by first determining the difference between asked and sale price, then dividing that difference by the original asked price. The result is expressed as a percentage. The sale price will most often be lower, so the spread is expressed as a negative percentage. For example, if a property was listed for $135,000 and sold for $129,500, the spread would be negative 4.1 percent (the difference of $5,500 divided by $135,000). In some markets (described as “hot” seller’s markets), however, the sale price could be higher than the asked price. For example, a property listed at $135,000 may sell for $142,000. In this case, the spread would be expressed as a positive number, 5.2 percent.

•Formula: Spread

(SP – AP) ÷ AP = S

where:

SP |

= sale price |

AP |

= asked price |

S |

= spread |

•Excel Program: Spread

A1: |

sale price |

B1: |

asked price |

C1: |

= SUM(A1/B1)/B1 |

The length of time a property is on the market is also a key indicator. The combination of spread and time on the market defines current supply and demand conditions and, of course, gains significance as an indicator when it is viewed as part of a trend. Remember, however, that this analysis is valid only when you restrict your study to the type of property you are analyzing. For example, if you are thinking of investing in single-family houses, you should exclude apartments and even duplexes or triplexes from your analysis of time on the market.

The analysis of time on the market is based on completed sales only. Thus, any listings that were withdrawn without being sold are not considered in this calculation. However, it may be useful and instructive to also track the number of withdrawn listings as a related indicator. To calculate time on the market, use the number of days. The alternatives (weeks or months) are more difficult to interpret. For example, 40 days versus 65 days is easier to comprehend than 6 weeks versus 9¼ weeks, or 11/3 months versus 21/6 months.

To figure out the number of days from a start date to a finish date, go to https://www.timeanddate.com/date/duration.html.

Most investors think of value in terms of profits. The difference between the purchase and sale price of a stock, bond, or property is, for many people, the single theme that defines whether a decision to invest has value.

While value defined as return on investment is crucial to the overall analysis of investing, other methods of quantifying value are equally important. The fundamental value of a property depends on timing within the real estate cycle, and timing may be defined by the inventory of properties, the spread between asked and sale prices, and the amount of time that property remains on the market. Beyond these measures, how can you test and compare value?

When an offer is made on a property, an appraisal is performed. This is normally a requirement of the lender, and it may not even occur until a serious buyer comes along. A smart seller may prepay for the appraisal and have it available to show to prospective buyers. This provides a means for demonstrating that the asked price is reasonable—especially if the appraisal value is higher.

For rental properties, another method of verifying values is to check property tax bills and the local assessed value. Property tax bills show the property’s assessed value, which is the value used to calculate the tax liability. This usually breaks down total value by land and improvements. Assessed value may lag well behind market value. In addition, assessed value is notoriously unreliable because of the time lag. If the local assessor’s office is understaffed, inefficient, or even unqualified, assessments may reflect those problems as well.

With this in mind, checking assessed value for several different properties provides you with a comparison between assessed value and asked price. This is valuable information, since it may reveal inconsistencies or demonstrate an important difference between the realistic market value of properties and the basis used for property taxes. If nothing else, the analysis of assessed values is useful in determining whether those values are reliable from one part of town to another.

•Formula: Assessment Ratio

A ÷ P = R

where:

A |

= assessed value |

P |

= asked price |

R |

= assessment ratio |

•Excel Program: Assessment Ratio

A1: |

assessed value |

B1: |

asked price |

C1: |

=SUM(A1/B1) |

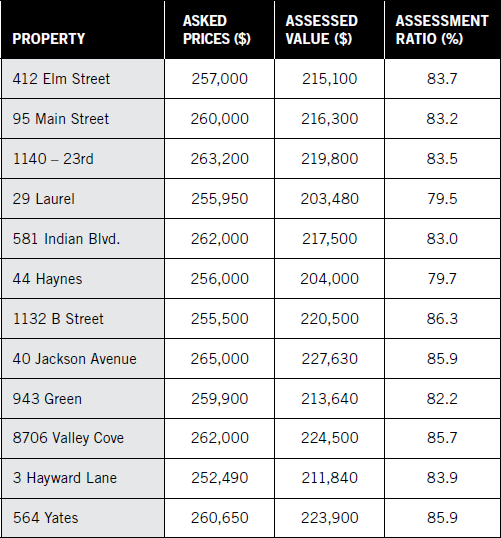

For example, suppose you check the assessed value for several properties on the market that you are thinking about purchasing. All are in the same city and are located in what you consider to be similar neighborhoods; the price ranges are similar as well. Comparing the assessed value to the asked price, you discover the relationships summarized in Table 1.2.

These estimates can be useful in comparing properties, especially if the assessment ratio is far off the average. However, you also have to remember that several other factors may distort the conclusion:

1.Adjusted assessed value is only an estimate. You cannot rely completely on what you discover from adjusting the assessed value. For example, in the previous comparison, one property was assessed last year, but the other had an assessment that was three years old. Using an average annual rate may distort actual assessed value.

2.Specific attributes of the property may be a factor. Even though two or more properties may be comparable in terms of both assessed and market value, attributes of those properties may affect both sides of the equation. These may include a den or office, an extra bathroom, the age and condition of the house itself, landscaping, the age of the roof, the heating and cooling system, or lot size, for example.

Table 1.2: Asked Prices and Assessed Value

3.Small changes between neighborhoods may affect assessed value. What assessors and appraisers call “comparable” neighborhoods may be vastly different in many ways. Even small changes will have an effect, such as proximity to transportation, schools, and shopping; high noise levels due to highways or airports; crime and safety levels; traffic flow; the mix of neighbors (by age, owner occupied versus rentals, or family size); and zoning (single-family residential versus mixed residential or higher-density zoning, for example).

4.Seller motivation may also be a factor in how the asked price is set. Finally, you also have to consider the variable of how motivated the seller is to close the deal. Some people are firm in their price and will not accept offers below that level. Others may be eager to sell and may have priced their homes below the appraised value to generate a fast sale.

Another source of information concerning value of a property is the seller’s tax return. This applies if the property in question has been used as a rental property; if the seller has used the house as a primary residence, there will not be any value in reviewing the tax return.

For rental properties, rents and expenses are reported on federal Schedule E. If you are thinking of purchasing a property that has been used as a rental, ask to see the seller’s Schedule E for the last two or three years. This enables you to judge the amounts of rent collected (net of vacancies, if applicable) and the level of recurring expenses involved: utilities, maintenance and repairs, property taxes, and landscaping.

Making a comparison between properties will be impossible if some properties were not used as rentals. In these situations, you need to estimate a comparable rental income and expense level based on mortgage payment levels and interest rates, property tax expenses, utilities, and market rents you expect to receive. Another potential problem is a seller’s refusal to show you any part of a tax return. However, this is also a matter of the seller’s motivation. If the property has been a profitable rental, then the Schedule E record will help complete the sale. If the seller is reluctant to disclose this information, it may be a sign that the property is not as attractive as an investment because of high maintenance or utilities expenses, vacancies, or other factors. If sellers are not willing to show you their property financial statements, that itself is a warning sign. After all, the request is reasonable. If you were thinking of buying a retail business from someone, you would expect to see the financial statements. The Schedule E is a financial statement for a rental property.

In addition to checking average annual rents, you will also be interested in checking the expense ratio between properties. Also called the operating ratio, this is a comparison between operating expenses and rental income. Operating expenses are the ongoing expenses of the property without including interest on the mortgage. Because interest varies based on rate, down payment, length of the mortgage term, and the beginning mortgage balance, it would not be accurate to use the owner’s average interest when comparing one property with another. So the operating ratio includes expenses other than interest on the debt; owner-paid utilities, property taxes, insurance, repairs and maintenance, and landscaping are typical. The ratio is expressed as a percentage, and it is most valuable when two or more properties are being compared.

•Formula: Expense Ratio

E ÷ I = R

where:

E |

= operating expenses |

I |

= gross income from rents |

R |

= expense ratio |

•Excel Program: Expense Ratio

A1: |

operating expenses |

B1: |

gross income from rents |

C1: |

=SUM(A1/B1)) |

A final version of value that is of special interest to real estate investors is the more traditional calculation of rate of return or return on investment. The various methods of calculating return may be used to judge results between properties, to set minimum standards, or to compare returns between real estate and other types of investments (savings accounts, mutual funds, or stocks, for example).

Two specific types of investment-return calculations are important to investors: return on investment and return on equity. Return on investment is the return based on the amount of cash invested; it provides you with comparative information on how well you have put your money to work in the selection of products (real estate, savings, stocks, and so on). Return on equity is different. This is the return based on the value of an investment. In the case of real estate, equity is likely to change over time, as a result of improved market value and periodic mortgage payments to principal. This is an important measurement for all investments because it provides you with a quantified comparative look at a particular investment’s success. To understand return on equity, consider what happens if a property’s market value is growing at a faster rate than the relatively slow pace of payments to principal on a loan. For example, suppose that a property’s market value is growing at 3 percent per year. Assuming a 20 percent down payment on a $150,000 purchase, the changes over 30 years will be quite different for investment and for equity. And in this comparison, return would be based on a sale price for the property or on an estimate of what that sale price would be.

To calculate return on investment, first estimate the total amount of cash that would be received upon sale of the property. This may be a complex number to estimate. You first need to assume the sale price, then deduct closing costs and the overall federal and state tax liabilities to arrive at the net cash you would receive upon sale. Of course, if you are calculating return on investment after the sale, you have the actual numbers available.

Once you determine the amount of cash received upon sale, deduct the cash-based investment in the property. This consists of your down payment plus the equity accumulated through payments on your mortgage loan. For example, on a $120,000 loan at 7 percent amortized over 30 years, your total principal payments after 10 years would be about $17,000. Added to a down payment of $30,000, your investment in the property would be $47,000.

The next step is to deduct the cash investment from the net cash received. This is the overall return on your investment. However, to make the calculation accurate, you also need to annualize the return, or reflect the return on average per year. This is necessary because it makes a difference when two properties produce the same return on investment, but one was held for five years and the other for ten.

•Formula: Return on Investment

(P – O) ÷ O = R

where:

P |

= proceeds upon sale |

O |

= original investment |

R |

= return on investment |

•Excel Program: Return on Investment

A1: |

proceeds upon sale |

B1: |

original investment |

C1: |

=SUM(A1-B1) |

Annualizing the return for any calculation involves restating the return for the entire holding period on an average annual basis—as if the investment were held for exactly one year. For investments held only a few months, use the number of months or days that the investment was owned. For longer periods, use years. In the following formula, the return (R) may represent a return on investment over a holding period (H) of 10 years. Thus, the average annual return (A) would involve dividing the return by 10.

•Formula: Annualized Return (Using Years)

R ÷ H = A

where:

R |

= return over entire holding period |

H |

= holding period (number of years) |

A |

= annualized return |

•Excel Program: Annualized Return (Using Years)

A1: |

return over entire holding period |

B1: |

holding period (number of years) |

C1: |

=SUM(A1/B1) |

When annualized return involves a calculation using months, you would divide the overall return by the number of months held and multiply the result by 12 (months).

•Formula: Annualized Return (Using Months)

(R ÷ H) * 12 = A

where:

R |

= return over entire holding period |

H |

= holding period (number of months) |

A |

= annualized return |

•Excel Program: Annualized Return (Using Months)

A1: |

return over entire holding period |

B1: |

holding period (number of months) |

C1: |

=SUM((A1/B1)*12) |

This formula works in situations where investments are held for periods shorter or longer than one year. For example, consider the following comparison: In one case, you held an investment for 8 months and received an overall return on investment of 7 percent. In another case, you held the property for 14 months and also received a 7 percent return:

(7 ÷ 8) * 12 |

= 10.5 percent |

(7 ÷ 14) * 12 |

= 6.0 percent |

The outcome in the two cases is far different when you annualize the returns. The shorter holding period yields an additional 4.5 percent, which is 75 percent more than the longer period, because of the annualization of the return.

Return on equity is far different from return on investment. The investment is defined as the amount of cash placed into the property, in the form of the original down payment plus periodic payments on the principal balance of the note. The investment basis has to be increased by the amount of any capital improvements, such as an addition, a new roof, or other major expenditures. For example, if you purchase a property for $150,000 and later add capital improvements that cost $25,000, your investment basis rises to $175,000. In comparison to basis in property, equity is the difference between the total value of the property and the amount owed on a mortgage loan.

•Formula: Equity

V – B = E

where:

V |

= current market value |

B |

= balance, mortgage debt |

E |

= equity |

A1: |

current market value |

B1: |

balance, mortgage debt |

C1: |

=SUM(A1-B1) |

Return on equity will also be calculated with different numbers. If you check back to the formula for return on investment, you will use a similar procedure, but instead of calculating your investment basis, you use current equity. For example, let’s assume that you bought a property for $150,000 and put $30,000 down. After 10 years, you have accumulated another $17,000 worth of payments, so your total investment would be $47,000. At that point, you would still owe about $103,000 on the original $120,000 loan. If you could sell the property today for $250,000, your equity—the difference between the current market value and the remaining debt—would be $147,000 ($250,000 less $103,000). This does not take into account the cost of selling. If you want to calculate the net return on equity, you would first deduct the cost of selling from the current market value. This number is called proceeds upon sale.

•Formula: Return on Equity

(P-B) ÷ (B÷Y) = R

where:

P |

= proceeds upon sale |

B |

= basis |

Y |

= years held |

R |

= return on equity |

•Excel Program: Return on Equity

A1: |

proceeds upon sale |

B1: |

basis |

C1: |

years held |

D1: |

=SUM(A1-B1)/(B1/C1) |

Return on investment and return on equity reveal valuable but different types of information. However, you are not limited to studying value only at the point of sale or when you are thinking about selling. You can also track returns over time.

Given the chaotic changes in the supply and demand cycle, viewing values or potential returns from one period to another without averaging out those returns is quite difficult. It is useful to investors tracking real estate values over time to use moving averages. This applies to following the market value of real estate, cash flow, and estimated return on equity.

With a moving average, you begin by selecting a field of values. For example, month-end or quarter-end average values of property in one city would provide you with an averaged view of movement in the real estate cycle. Then you add the values in the field and divide the total by the number of fields. For example, if you track real estate values at the end of each quarter over three years (12 quarters), you add the values together and then divide by 12. In a typical moving-average analysis, the field is shifted with each new period so that you always count the same number of fields. In the preceding example, you would always count the latest value, add it to the previous 11 values, and use the average to make the latest entry on a chart.

•Formula: Moving Average

(V1 + V2 + . . . Vf) ÷ N = A

where:

V |

= values in the selected field |

1, 2, . . . f |

= first, second, remaining, and final values |

N |

= number of values in the field |

A |

= moving average |

•Excel Program: Moving Average

Based on the example of 12 values in the field: |

A1 through A12: values of V1 . . . V12 |

B12: number of values in the field |

C12: =SUM(A1:A12)/B12 |

In some circumstances, it is necessary to use a weighted moving average. This is applicable when the outcome will be more accurate than the outcome if you use a simple moving average. The theory behind weighting is that the latest information is more important than earlier, outdated information and should be given greater weight. There are many ways to weight a moving average. For example, you may count each value except the most recent only once, but count the most recent value twice. That gives the most recent entry in the field twice the weight of the preceding values. If there are 12 values in the field and you double-weight the latest entry, you divide the total by 13 to arrive at a weighted moving average. Another method is to add ever-higher weight levels for each value, but this becomes far more complex when a lot of values are involved. For example, with 12 values, you would weight the latest entry by a factor of 12 and, as you move further back, use weights equal to 11, 10, 9, and so on. The total would then be divided by 78, the sum of the digits of the weighted values (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and so on). The formula used as an example weights the latest entry twice.

•Formula: Weighted Moving Average

(V1 + V2 + . . . (Vf x 2)) ÷ (N + 1) = A

where:

V |

= values in the selected field |

1, 2, . . . f |

= first, second, remaining, and final values |

N |

= number of values in the field |

A |

= weighted moving average |

•Excel Program: Weighted Moving Average

Based on the example of 12 values in the field: |

|

A1 through A12: values of V1 . . . V12 |

|

number of values in the field |

|

C12: |

=SUM((A1:A12)+A12)/(B12+1) |

In this formula, the final value (the latest entry) is increased by two in order to give it greater weight. The entire field is then multiplied by the number of fields plus 1 (to account for the weighting). If the final value were weighted by a factor of three, you would need to add cell A12 twice because the number of values would be greater. For example, in a field of 12 values, weighting the latest entry by three times would bring the total up to 14; thus, the divisor would make the weighted average accurate.

Another method that provides a weighted value is called an exponential moving average. This is a fairly complex calculation, but it can be programmed using an Excel spreadsheet. The five steps in the formula are summarized here, using the example of six fields in the moving average, with values of 34, 22, 44, 62, 16, and 11, and with the latest value to be added in of 17:

1.Compute the exponent by dividing 2 by the number of fields in the moving average.

2 ÷ 6 = 0.333

2.Compute the average for the six previous entries.

(34 + 22 + 44 + 62 + 16 + 11) ÷ 6 = 31.5

3.Subtract the latest value from the moving average to find the new value.

31.5 – 17 = 14.5

4.Multiply the new value by the exponent (from step 1).

14.5 * 0.333 = 4.833

5.Add the result of step 4 to the previous moving average.

4.833 + 31.5 = 36.333

•Formula: Exponential Moving Average

[(V1 + V2 . . . Vf) ÷N) – L] x (2 ÷N) + [(V1 + V2 . . . Vf) ÷N)] = NA

where:

V |

= values in the selected field |

1, 2, . . . f |

= first, second, remaining, and final values |

N |

= number of values in the field |

L |

= latest entry |

NA |

= new moving average |

Applying the formula to the previous example:

[(34 + 22 + 44 + 62 + 16 + 11) ÷ 6)] – 17 * (2 ÷ 6) +

[(34 + 22 + 44 + 62 + 16 + 11) ÷ 6)] = 36.333

On an Excel spreadsheet, the same calculations are summarized as this series of formulas:

•Excel Program: Exponential Moving Average based on example of six initial values plus a seventh value

A1: |

Number of fields |

A2: |

=SUM(2/A1) |

A3: |

Value 1 |

A4: |

Value 3 |

A5: |

Value 3 |

A6: |

Value 4 |

A7: |

Value 5 |

A8: |

Value 6 |

A9: |

=SUM(A3:A8)/A1 |

A10: |

=SUM(A10*A2) |

A11: |

=SUM(A11+A9) |

The exponential moving average may be excessively complex for most applications, but it is instructive to know how to perform the calculation. Using the Excel spreadsheet formula, the exponential moving average is reduced to a calculation involving only a single new entry for each period. This reduces the complexity. For exceptionally long periods of study, the exponential moving average formula makes the moving average easier to manage. As with all types of formulas, even simple or weighted moving averages, the use of formulas on spreadsheets makes calculation easy and fast. For most investors, valuation is a smart starting point. However, valuation itself is also a matter of detailed comparison among properties. Appraisers use a variety of methods to establish the market value of properties. These techniques are explained in Chapter 2.