Real estate has the most complex tax rules of all investment markets. Income tax rules generally do not allow investors to deduct losses on real estate programs, unless those losses offset similar gains or, when properties are sold, reduce the net gain that is reported. So those who place money in limited partnerships today—which were favored tax-shelter programs many years ago—cannot use those programs to produce losses.

When it comes to direct ownership of rental property, the rules are different. Real estate investors are allowed to deduct annual losses. This makes real estate the last remaining legal tax shelter, a feature that draws many people to this market. The difference that tax savings can make in the overall cash flow often justifies an investment that would otherwise not produce a positive or breakeven outcome. For many, the difference consists of the reduction in personal taxes.

The first rule to be aware of in getting a grasp of real estate tax rules is the limitation on deductions for passive losses. By definition, passive income is any income from activities that you do not manage directly. So a limited partnership, in which general partners make all of the decisions and limited partners have no say in management, is a form of passive activity.

In the tax-shelter days, limited partners could deduct losses without limitation. Because depreciation rules were liberal, it was possible for higher-income-bracket investors to claim deductions far above the amount they invested. For example, in some programs, it was possible for someone to invest $10,000 and claim a loss of $30,000. Because the loss was three times greater than the amount invested, such a program was referred to as a “3-to-1” write-off. Up until the early 1980s, the top tax bracket was 50 percent, so claiming a deduction for a $30,000 “loss” produced tax savings of $15,000:

Net loss |

$ 30,000 |

Tax rate 50% |

– 15,000 |

Tax savings |

$ 15,000 |

Less amount invested |

10,000 |

Net savings |

$ 5,000 |

The abuse of the system was so widespread that new tax laws were enacted. Among the most important was the Tax Reform Act of 1986. This law and other reforms meant to curtail tax-shelter programs included three important changes in the tax rules:

1.Passive loss restrictions. Losses from investments were no longer allowed when investors did not “materially participate” in the management of the property. Such losses had to be offset against passive gains or carried forward until the properties were sold.

2.At-risk rules. Under the old rules, investors could claim losses far higher than their actual investment basis. One scheme involved purchasing art at one amount, then getting a high appraisal and donating the art to a museum. This created a big loss. For example, buying art for $10,000 and donating it at an appraised value of $50,000 created a huge tax write-off. The new at-risk rules limited deductions to the amount actually put into a program through cash or notes that had to be paid at some time in the future.

3.Revised depreciation rules. Under the old tax system, real estate could be depreciated rapidly using accelerated methods. For example, an investor could claim depreciation losses over a relatively short number of years and at accelerated rates. Under today’s rules, residential property has to be depreciated, without acceleration, over 27.5 years.

The material participation rule distinguishes directly owned real estate from a passive investment. In a limited partnership, for example, the limited participants are by definition not materially involved in managing the investments. But when you select properties, interview tenants, collect rent, perform or supervise repairs, and make other important decisions on your own, you probably meet the standard for material participation. The law says that material means regular, continuous, and substantial. That means that landlords need to set rent levels, approve major expenses, and qualify tenants. Even if the day-to-day decisions are made by a management company, you can still qualify under the material participation rule. The qualification is important because in order to deduct losses, you need to meet this standard.

The maximum loss you can claim each year is $25,000. You can deduct up to this amount as long as you materially participate and as long as your adjusted gross income is below $100,000. If your income is above that level, your maximum allowable deduction for real estate losses is reduced by 50 cents for each dollar of excess.

•Formula: Maximum Loss Allowance

$25,000 – (( A – $100,000 ) ÷ 2) = L

where:

A |

= adjusted gross income |

L |

= maximum loss allowed |

•Excel Program: Maximum Loss Allowance

A1: |

adjusted gross income |

B1: |

=SUM(25000-(A1-100000)/2) |

For example, if your adjusted gross income is below $100,000, all of your net losses up to $25,000 can be deducted. But if your gross income is higher, an adjustment has to be made. If your adjusted gross is $106,000, for example, the maximum allowed loss would be:

$25,000 – (( $106,000 – $100,000) ÷ 2) = $22,000

An additional adjustment also has to be made. Under normal circumstances, adjusted gross income (AGI) refers to gross income for tax purposes, minus adjustments to gross income (for individual retirement account contributions, student loan interest, moving expenses, and other such items). However, for this calculation, you need to use what is called modified adjusted gross income. This is normally gross income without adjustments. You cannot deduct student loan interest, individual retirement account contributions, self-employment tax deductions, or tuition, for example. So if your adjustments to gross income are substantial, it could raise the modified AGI, changing the calculation of maximum deductible real estate losses.

The tax rules are beneficial for directly managed real estate, even with the complexities of computing allowable deductions and calculating depreciation (explained in the “Depreciation Methods” section later in this chapter). The method of reporting rental income and expenses is further complicated by a requirement that each property has to be itemized separately. Schedule E is the tax form used for summarizing real estate profit or loss. Each property has to be listed in a separate column. This becomes important if and when you cannot deduct the entire loss you report each year; those losses may need to be carried over and claimed as a reduction of profit upon sale of the property. So when you have several properties, you also need a record of how expenses were broken down among them.

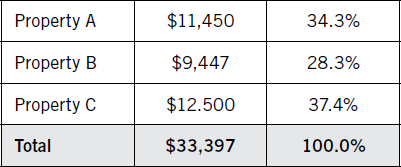

There are two important proration tasks, given the quirky tax rules. The first is how you assign expenses to each property when those expenses do not specifically pertain to any one property. The second is how to track and assign excess net losses. In both instances, the most consistent and reasonable method is based on a proration of rental income. You previously saw how expenses are prorated based on the percentage of the rent earned by each property. To review: You own three properties. The total rents received last year were as shown in Table 11.1.

This proration—which is called expense allocation, revenue share—is used to assign expenses such as depreciation on a truck or landscaping equipment, professional fees, and telephone expense. The specific expenses that you can identify as pertaining to individual properties (such as mortgage interest, property taxes, insurance, and utilities) are simply assigned to the column for each property individually.

The second area in which proration is required involves assigning carryover losses for future deduction. It would not be reasonable to claim all carryover losses against the first property sold, because some form of orderly proration is more reasonable. So you can break down and track losses based on the proration of net losses.

•Formula: Carryover Loss Allocation

L ÷ T = A

where:

L |

= loss reported for the property |

T |

= total net loss, all properties |

A |

= allocation percentage |

•Excel Program: Carryover Loss Allocation

A1: |

loss reported for the property |

B1: |

total net loss, all properties |

C1: |

=SUM(A1/B1) |

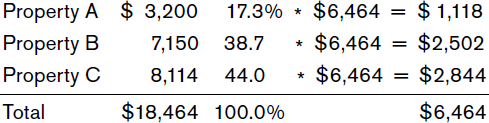

For example, if you owned three properties, you may have the following losses reported for the year:

Property A |

$ 3,200 |

Property B |

7,150 |

Property C |

+ 8,114 |

Total |

$18,464 |

If your modified AGI for the year was $126,000, your maximum deductible loss is reduced from $25,000 to $12,000 ($25,000 less one-half the gross above $100,000, or $13,000 = $12,000 net). This provides you with an excess of $6,464 for the year ($18,464 less the maximum of $12,000). This loss can be assigned on the basis of prorated overall net losses:

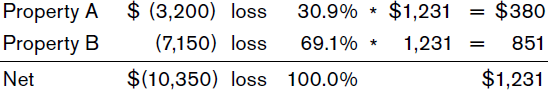

A complication arises when some properties have net losses, but others have gains. In these situations, you should calculate the proration of carryover loss using only the properties with reported net losses; leave properties on which a gain is reported out of the equation. This occurs when depreciation for one property is lower than average, or when one property’s mortgage interest is below the average. For example, let’s assume that the reported outcome for the three properties included the following breakdown:

Property A |

$(3,200) |

loss |

Property B |

(7,150) |

loss |

Property C |

8,119 |

profit |

Net |

$(2,231) |

loss |

If the modified adjusted gross income was $148,000, the maximum deduction would be reduced by $24,000 (one-half the income above $100,000), so the allowable net loss will be only $1,000. The carryover should be assigned to the two properties reporting a net loss on a prorated basis. The other property is excluded because it reported a gain. So the excess carryover loss will be $1,231 ($2,231 minus $1,000):

Year-to-year gains or losses on investment property are reported on Schedule E. Capital gains are reported on Form 4797 and Schedule D. The reporting procedure requires calculation of the net capital gain or loss. A capital loss deduction is limited to a maximum of $3,000 per year, so any losses above that level have to be carried forward and applied in future years.

Our concern here is with how the net capital gain or loss is computed. While a simple example of a capital gain can be defined as the difference between the purchase price and the sale price, the calculation for real estate involves four additional calculations:

1.Adjusted purchase price including any deferred gains. The actual purchase price of the property may not be identical to its basis. For example, if the property was purchased through a deferred gain, the gain is brought forward and used to reduce the basis in the new property.

2.Adjustments for unclaimed carryover losses. Any losses that were not used and have been carried forward are added to the basis in the property (or deducted from the realized sale price), which has the effect of reducing the reported capital gain.

3.Recapture of depreciation. All depreciation claimed during the time the property was owned is deducted from the basis (or added to the sale price), so the gain is increased and more taxes are due (or a net loss is reduced).

4.Calculation of adjusted sale price. The adjusted sale price is the agreed-upon price minus closing costs.

•Formula: Capital Gain or Loss

(S – Cs) – L + D – (P – Cp – G) = N

where:

S |

= sale price |

Cs |

= closing costs at sale |

L |

= carryover losses |

D |

= depreciation claimed |

P |

= purchase price |

Cp |

= closing costs at purchase |

G |

= deferred gains |

N |

= net capital gain or loss |

•Excel Program: Capital Gain or Loss

A1: |

sale price |

B1: |

closing costs at sale |

C1: |

carryover losses |

D1: |

depreciation claimed |

E1: |

purchase price |

F1: |

closing costs at purchase |

G1: |

deferred gains |

H1: |

=SUM(A1-B1-C1+D1-E1+F1-G1) |

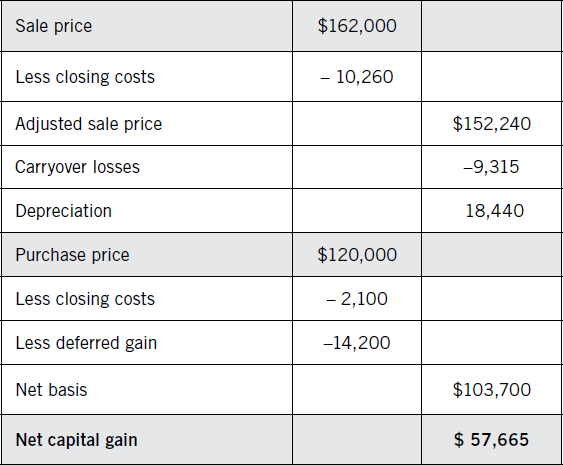

For example, assume the following: You sold property this year for $162,500, minus closing costs of $10,260. You also had carryover losses of $9,315. Depreciation claimed during the property’s holding period was $18,440. The original purchase price was $120,000 less closing costs of $2,100. However, the purchase was made as part of a tax-deferred exchange involving a gain on a previous sale of $14,200. The net capital gain is summarized in Table 11.2.

Table 11.2: Net Capital Gain

The overall effect of this is to report a net gain that accounts for the actual profit, adjusted for depreciation and carryover losses, and to calculate the taxes due based on the net gain. In the case of a net loss, the maximum of $3,000 per year applies, and any excess has to be carried forward and used in future years.

Many of the real estate calculations used to arrive at after-tax cash flow and capital gains involve depreciation expense. This expense does not involve payments of cash but is a calculated annual allowance. You are allowed to claim depreciation based on the type of property and its depreciable basis. In the case of real estate, land cannot be depreciated, and improvements have to be written off (depreciated) over a period of 27.5 years using the straight-line method (meaning that the same amount is claimed each year).

Other types of property (vehicles or landscaping equipment, for example) can be depreciated over shorter periods and on an accelerated basis. This means that a higher deduction is allowed in the earlier years, and the deduction declines over the course of the recovery period. Straight-line depreciation is the easiest to calculate.

•Formula: Straight-Line Depreciation

B ÷ P = D

where:

B |

= basis of asset |

P |

= period (in years) |

D |

= annual depreciation |

•Excel Program: Straight-Line Depreciation

A1: |

basis of asset |

B1: |

period (in years) |

C1: |

=SUM(A1/B1) |

Some assets can be depreciated using accelerated depreciation methods. Under the most common method, the annual allowance for accelerated depreciation is based on the straight-line method, but with higher depreciation allowed in the earlier years.

•Formula: Accelerated Depreciation

(B ÷ P) * R = D

where:

B |

= basis of asset |

P |

= period (in years) |

R |

= acceleration percentage |

D |

= annual depreciation |

•Excel Program: Accelerated Depreciation

A1: |

basis of asset |

B1: |

period (in years) |

C1: |

acceleration percentage |

D1: |

=SUM(A1/B1)*C1 |

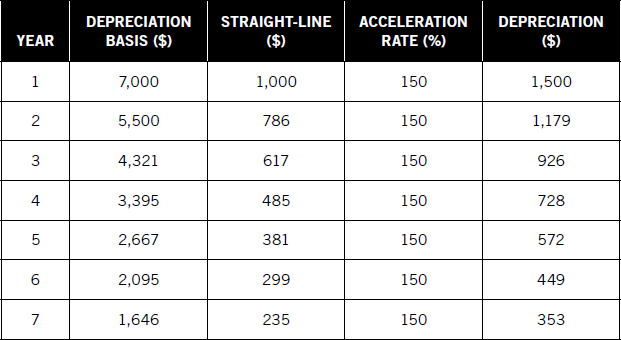

For example, if the acceleration rate is 150 percent (expressed as 1.5 in the formula), each year’s depreciation would be 150 percent higher than straight-line depreciation, based on the undepreciated basis of the asset at the beginning of the year. If the asset is valued at $7,000, and you are depreciating the asset over seven years, the straight-line rate would be $1,000 per year for each of the seven years. In accelerated depreciation, however, each year’s depreciation would be as shown in Table 11.3

Table 11.3: Accelerated Depreciation

In practice, use of the accelerated method involves reverting to straight-line in the last few years. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has published tables showing how to compute depreciation under each method and what percentages to claim as depreciation each year.

To order Form 4562 (used to report depreciation) or the publication providing instructions and tables for each depreciation method, check the IRS websites at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f4562.pdf (form) or https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i4562.pdf (instructions).

Two so-called conventions are also used to simplify the calculation for the first year. You are not allowed to claim a full year’s depreciation expense for the year in which an asset is first placed into service. Depending on the type of asset, you are required to use either the half-year convention or the mid-month convention.

The half-year convention makes all calculations within a class of assets uniform each year. The first-year calculation is based on the assumption that newly acquired assets were purchased exactly halfway through the year.

•Formula: Half-Year Convention

B ÷ 2 = H

where:

B |

= basis of the asset |

H |

= half-year depreciation base, first-year |

•Excel Program: Half-Year Convention

A1: |

basis of the asset |

B1: |

=SUM(A1/2) |

For example, suppose the basis of an asset is $80,000. Using the half-year convention, first-year depreciation will be based on the assumption that the asset was acquired one-half of the way through the year:

$80,000 ÷ 2 = $40,000

This does not change the basis of the asset; the full basis of $80,000 is used in subsequent years. An alternative method for figuring this out would be to first calculate depreciation and then reduce the amount by half.

In the mid-month convention, the first-year rate is computed on the assumption that all assets in a particular class were put into service exactly halfway through the acquisition month. Thus, if you acquire an asset in January, under the mid-month convention, the depreciation would be calculated as though the asset were in service for 11½ months of the year.

•Formula: Mid-Month Convention

(B ÷ 24) * P = M

where:

B |

= basis of the asset |

P |

= number of half-month periods |

M |

= mid-month depreciation basis, first year |

•Excel Program: Mid-Month Convention

A1: |

basis of the asset |

B1: |

number of half-month periods |

C1: |

=SUM(A1/24)*B1 |

For example, if the basis of an asset was $80,000 and it was acquired at any time during January, the first step would be to divide the basis by 24 (half-month periods), and then to multiply the sum by the number of periods the asset was in service. From January 16 through December 31, there are 23 half-month periods. Applying the formula:

($80,000 ÷ 24) * 23 = $76,667

Rounded up, depreciation for the first year would be based on this reduced basis. If the asset had been acquired in May, there would remain 15 half-month periods, so the calculation would be:

($80,000 ÷ 24) * 15 = $50,000

An alternative is to first calculate depreciation and then apply the applicable number of periods. For example, if the straight-line method were to apply and the depreciation period was 27.5 years, first-year depreciation for an asset acquired in May would be:

($80,000 ÷27.5 years) * (15 ÷ 24) = $1,818

You can verify this calculation by returning to the previous method, where you concluded that the first-year basis for depreciation was $50,000. Again applying the assumption of straight-line rate and 27.5 years:

$50,000 ÷ 27.5 years = $1,818

Both methods produce the same result. In this case, subsequent-year depreciation would be based on the original $80,000 basis and 27.5 years in the recovery period:

$80,000 ÷ 27.5 years = $2,909

You would be allowed to claim a depreciation deduction over 27.5 years in the amount of $2,909 per year (after the first year). Each year’s depreciation will be:

Year 1 |

$1,818 |

Years 2–27 ($2,909 * 26) |

75,634 |

Year 28 (remaining balance) |

+ 2,548 |

Total depreciation |

80,000 |

The rules for depreciation are not complex, given that the IRS publishes a series of tables providing guidance as to how each class of assets is to be depreciated each year. A wise move is to calculate depreciation once for the entire recovery period and then write in each year’s amount on a worksheet.

The final point concerning taxes on real estate brings us to yet another significant tax benefit: As a real estate investor, you can put off paying taxes on your capital gains. A stock market investor who sells stock at a profit pays taxes in the year in which the sale is completed and cannot simply replace the stock with the stock of another company. As a real estate investor, however, you enjoy considerable tax advantages.

Even homeowners have the extraordinary benefit of being allowed to deduct up to $500,000 of capital gains on the profit from selling their primary residence. (This applies to married couples; single filers and heads of household can deduct up to $250,000.) By definition, your primary residence is the home that you have lived in for at least 24 months out of the last 60 months. Conceivably, you could have two primary residences within a five-year period. However, you can claim a tax-free profit from such a sale only once every 24 months at the most. Beyond that, there are no restrictions. So a married couple could claim a tax-free sale as often as every two years.

This raises some interesting possibilities for real estate investors. You can rent out a property for many years, claim depreciation and other expenses, and then convert that property to your primary residence. As long as you live there for at least 24 months, you do not have to pay taxes on the capital gain, with one exception: You do have to declare as income the amount of depreciation claimed during the period when the property was used as investment property and pay taxes on that amount.

Another attractive feature is the 1031 exchange (also called a like-kind exchange), which provides that you are allowed to defer the gain on property as long as you meet specific rules. These include the requirement that you find a replacement property and close its sale within six months after you place the previous property on the market. You also need to purchase properties that cost as much as the sale price of the previous property. (If you do not exceed that price, the difference is taxed in the year of sale, and only the remaining profit can be deferred.)

The IRS publishes a useful article explaining the rules for the 1031 exchange. It can be viewed at the IRS website at https://www.irs.gov/uac/like-kind-exchanges-under-irc-code-section-1031.

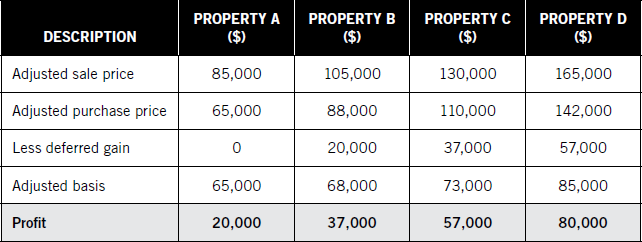

When you replace one property with another and use the 1031 exchange, the deferred gain is carried forward and used to reduce the basis in the new property. In theory, you could continue to defer profits on investment property over a period of many years.

In this example, the amount of deferred gain increases with each subsequent purchase and replacement. As long as you replace a sold house with another of equal or greater value, and as long as the transaction is completed within 180 days, you are allowed to use the 1031 exchange to defer paying taxes on investment real estate.

This is not the same as avoiding taxes altogether. The liability eventually has to be paid. However, this beneficial rule allows you to put off making the tax payment until sometime in the future. In a 1031 exchange, computation of the new basis requires adjusting for the accumulated deferred gain from previous sales.

•Formula: New Basis in 1031 Exchange

P – D = N

where:

P |

= adjusted purchase price |

D |

= deferred gain |

N |

= new basis |

•Excel Program: New Basis in 1031 Exchange

A1: |

adjusted purchase price |

B1: |

deferred gain |

C1: |

=SUM(A1-B1) |

In Table 11.4, the purchase price of Property D was $142,000, but that basis was reduced by $57,000 in deferred gains on previous property transactions. Thus, upon the sale on that property, the investor reports a profit of $80,000 (the current gain of $23,000 plus accumulated deferred gains of $20,000 on property B and $37,000 on property C)—or, if this is practical, the investor can continue deferring the gain by using the 1031 exchange again.

The 1031 exchange is allowed for real estate investors but not for other investors. This feature adds to the attractiveness of real estate. Additionally, you decide when to sell property or when to continue holding it. You can time either a 1031 exchange (based on market conditions, for example) or a taxable final sale (based on your current-year income and financial situation). The 1031 exchange is a superb feature in the tax law, enabling investors to continually trade up and accumulate wealth while improving their cash flow—all without having a portion of their equity taken in the form of income taxes.

Table 11.4: Like-Kind Exchange

When you consider the combined features of the tax-deferred exchange and the yearly tax benefits (such as being allowed to claim losses from real estate activity), the potential risks associated with cash flow and market forces often are worth taking. Dealing with tenants, lenders, and real estate agents can be complex, and for some people, this excludes real estate as a viable investment. For those investors, hiring a professional management company often solves the problem. For people who enjoy working with tenants and the other people involved, real estate investing is complex and challenging, but it can also be exceptionally rewarding—as a tax shelter, a generator of positive cash flow, and a profitable, long-term investment.

The next—and final—Chapter, 12, shows how various building and land measurements are calculated. These are essential for anyone who is interested in raw land purchases, or for figuring out exactly how to compare two or more potential investments on the basis of actual square feet.