28

THE FOUNTAIN OF PARADISE

The book of Genesis’s description of the four rivers of Paradise indicates very strongly that the Garden of Eden was located in historical Armenia, modern-day eastern Turkey, with the epicenter being somewhere in the vicinity of the enigmatic plain of Mush, a vast expanse of congealed lava, created across tens of thousands of years by the outpouring of the various volcanoes that surround it. After crumbling to dust, the lava was transformed into a rich soil that has made Mush one of the most fertile regions in eastern Turkey, noted in the past for its wheat and tobacco. Vineyards were also once numerous, with a fair wine apparently being produced.1

THE PLAIN OF MUSH

The plain itself lies at a height of just over 4,100 feet (1,250 meters) above sea level and is approximately 40 miles (64 kilometers) in length from east to west and 10 miles (16 kilometers) broad. Visible at its eastern end is the extinct volcano Nemrut Dağ (Mount Nimrod), which takes the form of a gigantic caldera half a mile (800 meters) in diameter, within which is an enormous crescent-shaped lake. Obsidian from Nemrut Dağ has been found at Göbekli Tepe.

The Murad Şu, or Eastern Euphrates, cuts right across the plain, dividing it in two, before vanishing into a narrow gorge at its western end. This creates a pass through the Eastern Taurus Mountains, along which the somewhat hazardous road to Diyarbakır winds its way. This was the old obsidian route from Bingöl and Lake Van to the various proto-Neolithic and Pre-Pottery Neolithic centers, such as Hallan Çemi, Çayönü, Nevalı Çori, and, of course, Göbekli Tepe.

Another gorge at the plain’s southeast corner forms a pass through the Eastern Taurus range, providing access to the university city of Bitlis (ancient Baghesh) and Lake Van while another pass, carved out by the Murad Şu, opens the way north toward Bingöl, both the town and the mountain, beyond which is the old Armenian city of Karin, modern-day Erzurum.

MONASTIC FOUNDATIONS

Some miles to the northwest of the town of Mush, the capital of the province of the same name, are the remains of Surb Karapet, or more correctly Surb Hovhannes Karapet Vank, the Monastery of Saint John the Baptist. Before its destruction at the time of the Armenian Genocide in 1915, it was a major place of pilgrimage, with Christians coming here from all over Armenia to venerate holy relics belonging to John the Baptist. According to tradition, Armenia’s great crusading churchman Gregory the Illuminator built the monastery on the site of important pagan temples destroyed by him and his army at the beginning of the fourth century. Today, Surb Karapet, which from old pictures looks more like a fairy-tale castle than a monastery, is little more than a few pathetic walls in the middle of a bustling Kurdish village, which has long since lost interest in its rich Armenian heritage.

Apparently, several monasteries were once to be found on the plain of Mush, which formed part of a royal kingdom called Taron, or Turuberan, where Armenian Christianity had its beginnings even before the arrival of Gregory the Illuminator in the fourth century.2 I could find information about just one other notable monastic ruin in the area, and this was Surb Arakelots (Holy Apostles), located in a mountain valley southeast of the town of Mush. However, an examination of what was known about Surb Karapet and Surb Arakelots, or, indeed, any of the other monasteries that once existed in the region, did not in any way feel similar to what I had seen and experienced in my dream.

THE TREE OF LIFE

Yet the more I recalled the strange ceremony taking place inside the gloomy church interior, the more I became convinced not only that the Eden monastery existed, but that the monks there had been elevating an object of great spiritual value. It had been removed from a plain, wooden box that acted as a reliquary (a relic holder). As to the nature of the relic, this seemed to be a blackened piece of wood, like a short, round section of a tree branch, some 2.5 inches (6 centimeters) in diameter and 7 to 8 inches (18 to 20 centimeters) in length.

Initially, I thought the monks might have identified this relic as a piece of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, which the Genesis account tells us was to be found in the Garden of Eden. However, this did not sit right with me, and very quickly I realized that I had this wrong. The relic was in fact thought to be a fragment of the Tree of Life, the other tree in the Garden of Eden. That felt absolutely right, especially as I had seen it being elevated during a ritual that seemed to celebrate life itself.

The monks, I suspected, believed that simply possessing this holy relic invoked a sense of the eternal life that Adam and Eve experienced before their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. The couple’s existence was sustained through their proximity to the Tree of Life, which, situated within the garden, was seen as a powerhouse of divine energy that transcended the normal laws of nature. Yet without the benefits of the Tree of Life, Adam and Eve, along with all their descendants, were doomed to suffer mortality in all its ugly ways, a just punishment for committing the original sin, or so the book of Genesis tells us.

That the monks of the monastery drew some kind of spiritual power from what they saw as a fragment of the Tree of Life made absolute sense. Combining the religious potency of this relic with the fact that the monastery was thought to have existed in the Garden of Eden would only have increased their faith in what they believed they were achieving here in this spiritual powerhouse. No wonder I could so vividly recall this archaic ritual that must have taken place before the assumed destruction of the monastery at the time of the Armenian Genocide.

I sensed strongly that the monastery in question existed somewhere in the vicinity of the plain of Mush. It was a perfect setting for the Garden of Eden, especially as high mountains surround it on all sides and from these come streams that feed all four rivers of Paradise.

FINDING OTHER EDENS

Despite this information, the most often quoted solution regarding the whereabouts of the Garden of Eden stems from the somewhat puzzling conclusion, first proposed by influential French theologian and pastor John Calvin (1509–1564), that the terrestrial Paradise was located in the vicinity of Basrah, in southern Iraq. Here the Euphrates and Tigris rivers were once thought to have come together and then parted again to form all four rivers of Paradise. The fact of the matter is that although these two great rivers do indeed converge here to form the Shatt al-Arab waterway, into which flows Iran’s Karun River (which some take to be the Gihon3), this hardly fits the evidence offered for the location of the Garden of Eden in the book of Genesis.

Others have suggested that the four “heads” of the rivers of Paradise refer to their mouths, meaning that we should be looking for the Garden of Eden where the Euphrates and Tigris empty into the Persian Gulf. This has prompted all sorts of complicated theories involving now-vanished rivers, with the most persuasive being that the Pison once ran through Arabia’s Wadi al-Rummah, emptying into the Persian Gulf close to the Shatt al-Arab waterway.4 As far-fetched as these claims might seem, they remain the most popular theories regarding the true site of the Garden of Eden.5

More incredible still is the view that the holy city of Jerusalem is the terrestrial Paradise, based on a few brief references in the Old Testament comparing the city to the Garden of Eden, along with a Jewish legend that speaks of Jerusalem as the center of the world.6 Once again, this is not simply the belief of lay people, but the opinion of theologians and historians, even though Jerusalem is located nowhere near any of the easily identifiable rivers of Paradise.

These theories have been put forth despite the fact that Armenian scholars have for many years attempted to convince the outside world that the terrestrial Paradise was located in their historical homeland. Their arguments go unnoticed because they are usually written in Russian Armenian, which very few non-Armenians can read. Even when their work is published in English, something is lost in translation, resulting in very few people taking it seriously.7

THE REVEREND MARMADUKE CARVER

Yet, as we have seen, Westerners do occasionally conclude that the area around the sources of the four rivers of Paradise constitutes the most likely site of the Garden of Eden. Dutch scholar Hadrian Reland worked this out at the beginning of the eighteenth century, although he was certainly not the first to do so. One of the earliest individuals to come to the same conclusion was the rather grandly named Marmaduke Carver (d. 1665), a former rector of Harthill in South Yorkshire. His fascinating work on the subject, entitled A Discourse of the Terrestrial Paradise, Aiming at a More Probable Discovery of the True Situation of That Happy Place of Our First Parents Habitation, was published posthumously in 1666, one year after his death.

Having learned that the Reverend Marmaduke Carver had identified the site of the Garden of Eden as Armenia Major, I decided to find out more about the churchman’s life and theories, so went in search of him and his book, beginning with his former parish of Harthill, near Sheffield. Yet here, in the local parish church, I found no mention of him, other than his name entered in a long list of rectors from medieval times to the present day.

One thing I did manage to establish was that toward the end of his life Carver had spent much of his time in the city of York, just 60 miles (97 kilometers) from Harthill. Here he had become chaplain to Sir Thomas Osborne (afterward Duke of Leeds), high sheriff of the county, delivering sermons in York Minster, the city’s famous cathedral. More significantly, I found that on his death in August 1665 Carver’s body had been laid to rest in the south aisle of the cathedral choir.

So after leaving Harthill, I traveled to York Minster, hoping to find some evidence of Carver’s gravesite. Yet no evidence of his interment remains today, not even the wall plaque that marked the spot. This was obviously a great disappointment, so after sitting down briefly in the choir area to meditate on what I should do next, I made the decision to visit the York Minster Library, located within the cathedral grounds. Here I was finally able to find out a little more about the fate of Marmaduke Carver’s memorial plaque. Originally it had borne an inscription in Latin, written by James Torre, an early historian of the minster, but this had been destroyed during restoration work in 1736. It was subsequently replaced with a new plaque, its inscription now in English. This, however, along with the site of Carver’s grave, has since been lost due to subsequent restoration work in the south aisle. Mercifully, both versions of the inscription have been preserved.*168 As you can see, it is a fitting epitaph to the churchman’s life and work, in particular his search for the terrestrial Paradise:

Reader, if you love piety, if you know how to value learning, you should know what a treasure lies under this stone, Marmaduke Carver, formerly rector of the Church of Harthill, but very well versed in . . . chronology and geography, an accomplished linguist, a fine speaker—the man, to wit, who . . . pointed out to the world the true place of the terrestrial paradise, (yet in death) made of the object of his admonitions, the celestial (paradise) which he recommended to the praise of his hearers to attain which we are filled with great longing. He was translated on this day of August 1665.9

During his stay in York, Carver had apparently spent much of his time conducting research for his book in the cathedral library, which is the largest of its kind in the country. It has a collection of around 120,000 volumes, 25,000 of which were printed before 1801, including 115 incunabula (tracts printed before 1501).

So it seemed only fitting that I should find that York Minster Library has two of the only remaining copies of Carver’s book in the country. Some cunning persuasion helped overturn the librarian’s decision not to allow me to view the title at such short notice, so I sat down ready to read what I hoped would provide me with some valuable insights regarding the true whereabouts of the Garden of Eden. I was not to be disappointed.

THE GREAT FIRE OF LONDON

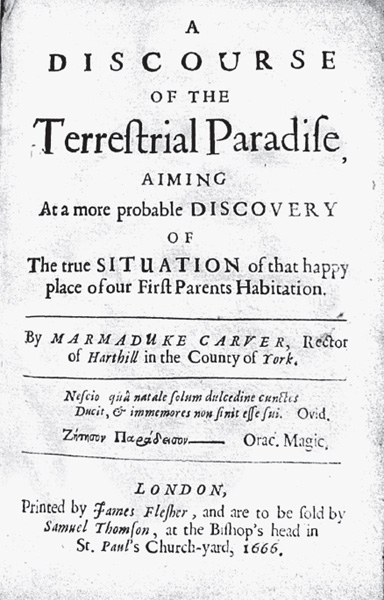

The small, leather-bound book placed before me on the reading desk felt very special indeed. It was printed in April 1666 by James Flesher of London and sold by one Samuel Thomson “at the Bishop’s head in St. Paul’s Church-yard” (see figure 28.1). Now, it is important to conjure a vision of the time, for 1666 was the year of the Great Fire of London, which burned from the second to the fifth of September and started in a bakery in Pudding Lane. This is just over 1,000 yards (1 kilometer) away from Saint Paul’s Cathedral, where Samuel Thomson had his bookshop at the sign of the Bishop’s Head (probably located in the inn’s thoroughfare). So unless this copy of Carver’s book had sold in the months leading up to the fire, it must have been among the stock salvaged after the fire had swept through Saint Paul’s churchyard, razing the old cathedral to the ground. I almost expected the book to exude a residual aroma of smoke and fire as I began to digest Carver’s findings on the true location of the terrestrial Paradise.

Figure 28.1. The cover of A Discourse of the Terrestrial Paradise, by the Reverend Marmaduke Carver, published in London, England, in 1666. It was arguably the first book to build a solid case for the terrestrial Paradise being located in historical Armenia.

A MERE UTOPIA

The tract’s opening address, dedicated to Gilbert Sheldon, the archbishop of Canterbury, makes it clear that the author has written the book in an attempt to dispel antiscriptorial thinking, begun in earnest by Martin Luther (1483–1546), which asserted that the Garden of Eden was “a mere Utopia, a Fiction of a place that never was, to the manifest and designed undermining of the Authority and Veracity of the Holy Text.”10 After this, in a long forward, Carver makes his case against the current most popular theory on the location of the terrestrial Paradise, that it was located where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers converge in Lower Mesopotamia, a view held, he says, not only by Calvinist reformers, but also by some Papist, or Catholic, scholars.11

Having successfully rebutted this theory, Carver proceeds, in a sound, scholarly manner, to build a case for Eden being located in Armenia Major, now part of eastern Turkey. Significantly, he explores ancient evidence suggesting that the Euphrates, Tigris, and Araxes rivers all derive from the same source.12 This, he says, was a single “fountain” in the “forests of Armenia,”13 situated in the vicinity of a lake known anciently as Thonitis, or Thospites,14 called also Arianias, or Arsissa,15 all names usually associated with Lake Van.

Carver cites the belief of various classical writers, including Strabo16 and Pliny,17 that some kind of proto-river, the true source of the Tigris, emerged from a primordial fountain, then discharged into the Thospites, or Lake Van, its waters so rapid, so powerful, that they did not mix with those of the “nitrous lake.” The proto-Tigris then reemerged beyond the lake’s southwest corner and sank down into a subterranean cave, only to reappear on the south side of the Eastern Taurus Mountains in the former Armenian province of Sophene, north of Diyarbakır. This then becomes the open source of the Tigris, which is known today as the Tigris Tunnel, or Birkleyn, from the Arabic birqat al-’ayn, “source of the river.”

Carver believed it was this primordial fountain, the true source of the Tigris, that brought forth the four rivers of Paradise.18 With this in mind, he concludes his scholarly discourse by proposing that the site of Eden, or “Heden” as he marks it on the accompanying map (see figure 28.2), was to be found between Sophene “and the fountains of Tigris, in the midst whereof, and upon the bank of the river, stood the Tree of Life. . . . Just about which place . . . we see . . . the nitrous Lake Thospites.”19

CHERUBIM WITH THE FLAMING SWORDS

Carver points out that after the proto-Tigris passes through the Thospites, it was said by the classical writers to reemerge in the region of Mount Niphates.20 This is the ancient name for Nemrut Dağ, the volcanic caldera situated just beyond Van’s western shoreline. Having concluded that the Fountain of Paradise lay between here and Sophene, or immediately south of the plain of Mush, he proposes that the cherubim, which God set up to guard the Tree of Life with flaming swords turning every way, were in fact the “flashings issuing out of some Lakes.”21

This is a very clever solution. Such “flashings” might easily describe the volcanic activity attached to Nemrut Dağ, which has erupted periodically since ancient times, the last time being in 1891, when the summit started “vomiting forth flames and lava,” destroying the villages at the base of the mountain.22

On this same matter, the Reverend W. A. Wigram and Sir Edgar T. A. Wigram in their book The Cradle of Mankind, published in 1914 following their celebrated travels in Kurdistan (eastern Turkey, northern Syria, northeast Iraq, and western Iran), observed:

It is held by many commentators that the site of the Garden of Eden was near modern Van and Bitlis, round about the headwaters of the Euphrates, the Tigris, the Araxes, and the Zab. If so, then the Garden of Eden now lies buried beneath the lava of these volcanoes; and where could we find fitter antitypes of the Cherubim with the flaming swords?23

It is unlikely that the Wigrams were aware of Carver’s work when they wrote their book. However, their statements suggesting that the volcanoes, as natural boundaries to the Garden of Eden, were themselves the cherubim wielding the flaming swords echo Carver’s thoughts completely.

And if the Garden of Eden is not encased in volcanic lava, then it could equally have been drowned, for one old Armenian legend asserts that it lies “at the bottom of Lake Van,” where it has been since the time of the Great Flood.24 This conclusion reflects the medieval belief that even if a terrestrial Paradise had once existed, then it would surely have been destroyed at the time of the Flood, which covered everything to the height of the highest mountains.

CARVER’S MAP OF PARADISE

Turning next to Marmaduke Carver’s detailed, though rather fantastic, map of Greater Armenia (see figure 28.2), we see the terrestrial Paradise marked under the Latin legend Heden regio quae et anthe (Eden region and caves). These words are sandwiched between the Thospites, or Lake Van, in the east, and Sophene in the west. Indeed, the inscription appears in the vicinity of the Eastern Taurus Mountains, which lie immediately beneath the plain of Mush, with eden deriving most probably from the Akkadian word edinu (Sumerian eden), meaning “plain” or “steppe.”25 Having said this, a recent academic trend sees eden as stemming from the West Semitic root ‘dn, meaning “to enrich, make abundant,”26 which remains possible, although less likely.

MOUNT ABUS

Passing across Thospites Lake on Carver’s map are two parallel lines that run north-south, representing the proto-Tigris flowing unaffected through its waters. They continue as dotted lines beyond the lake’s northern shores, indicating that this is the incoming subterranean river alluded to in the writings of classical writers, such as Strabo and Pliny, and that at its source was the primordial foundation from which all four rivers of Paradise took their course. Geographically, the lines originate from between a line of mountains, one of which is marked with the legend “Abus Mons.”

Abus Mons, or Mount Abus, also spelled Monte Abas,27 or Aba,28 is mentioned in the works of both Pliny29 and Strabo, the latter of whom writes that from its summit “flow both the Euphrates and the Araxes, the former towards the west and the latter towards the east.”30 This can only be a reference to Bingöl Mountain, of which it is said: “The Araxes rises near Erzurum (Turkey) in the Bingöl Dağ region: there is only a low divide separating it from the headwaters of the Euphrates river.”31 We should recall that Bingöl was the center of the obsidian trade in the Armenian Highlands in the proto-Neolithic age and can also be identified with Gaylaxaz-ut, or Paxray, the Wolf Stone Mountain of Armenian folklore (see chapter 24).

Figure 28.2. Section from Marmaduke Carver’s A Discourse of the Terrestrial Paradise showing “Heden,” or Eden, between Lake Van (the Thospites, in the center) and the ancient kingdom of Sophene. Note the proto-Tigris coming down from the north, close to Abus Mons (Bingöl Mountain), and flowing uninterrupted through the lake.

THE SOURCE OF MANY RIVERS

Dutch scholar of Semitic studies Martijn Theodoor Houtsma (1851–1943), in the Encyclopaedia of Islam, made it even clearer in 1927, when he wrote: “No fewer than six important water-courses rise in this erosion [i.e., Bingöl Mountain’s innumerable glacial pools], in which Armenian tradition for this reason places the site of the biblical Paradise.”32 These “water-courses” are broken down in the following manner: in the northwest is the source of the Araxes, in the west is the Tuzla Şu, which becomes a major branch of the Western, or Northern, Euphrates, and the Bingöl (or Peri) Şu, which, as we saw in chapter 24, was known to the native Armenian population as the Gail, or “Wolf,” River. It too rises on the west side of Bingöl Mountain, then heads off in the direction of Baghir and Shaitan Dağ. In the southwest part of the massif rises the Gönük Şu; in the south, the Çabughar Şu; and in the east and northeast, the Khınis Şu. The last four mentioned rivers, including the Peri Şu, all join the Eastern, or Southern, Euphrates.

What was it that led the Reverend Marmaduke Carver to conclude that the primordial fountain that gave rise to the four rivers of Paradise existed in the same mountain range as Abus Mons, in other words Bingöl Mountain? Was he aware of Strabo’s reference to Abus Mons as the source of both the Euphrates and Araxes?33 It is possible, although if this were the case then surely he would have mentioned it. More likely is that it was quite simply an intuitive decision based on whatever evidence he had in hand when he came to write his fascinating book.

Strangely, Carver does not identify the Gihon with the Araxes, nor does he associate the Greater Zab with the Pison. Instead, he sees major waterways that split away from the Tigris and Euphrates as evidence for the existence of these other two rivers. The Pison, for instance, he has entering neighboring Persia and linking, eventually, to the Indus, one of the longest rivers in Asia. Yet this vagueness should not detract from Carver’s remarkable insights into the geographical location of the Garden of Eden, and we are by no means finished with his findings quite yet.

I felt the need now to focus my efforts more toward Bingöl Mountain, the Abus Mons of antiquity, in an attempt to better understand why Carver believed that here somewhere was the primordial fountain of life, and why the Dutch scholar Martijn Houtsma concluded that this was “the site of the biblical Paradise.”