39

THE RETURN TO EDEN

Monday, September 10, 2012. After a night spent in a dismal hotel on the outskirts of Istanbul, I journeyed on to eastern Turkey. From the small airport at Mush, a taxi took me to the hotel, which lay on the edge of town. Close by was the road out to the villages of Kızılağaç and Suluca, near to which I would find Dera Sor, the ruins of the Yeghrdut monastery.

The next morning, over breakfast, I was able to appreciate exactly where I was for the first time. Through the hotel’s panoramic windows I could see the plain of Mush stretching away in every direction, beyond which was a seemingly impenetrable wall of mountains, reminding me of the seven mountains that encircle the Garden of Righteousness, according to the book of Enoch.1 Only toward the east did they seem to lower slightly, and here I thought I could make out the summit of Nemrut Dağ, the extinct volcano on the western shores of Lake Van.

THE TAXI RIDE

With breakfast over I waited in the lobby as the hotel owner made various phone calls. These resulted in a taxi driver arriving just after ten, although the guide-interpreter situation was not good, apparently. For two hours I drank sweet black tea and waited, until finally two guys turned up, both quite young, one of whom said he was usually paid the going rate as an interpreter for the European Union, which worried me slightly due to the potential expense. The other was his friend, who also spoke good English. Very quickly we were in the taxi on our way out to Suluca.

No one had heard of Dera Sor, or Yeghrdut, which seemed bizarre. I was telling them about a sacred site, an ancient ruin of substantial size with a fascinating history spanning nearly two thousand years, yet nobody knew a thing about it. If it had not been for the images I had brought along that showed Dera Sor on Google Earth, my new friends might not have believed it even existed.

As the taxi left the outskirts of town, I followed the route closely to ensure we were going in the right direction, but the driver knew Suluca, and very soon we were on a side road leading toward the foothills of the Eastern Taurus Mountains and a cluster of prefabricated buildings. We stopped to ask the way to Dera Sor, and an old man pointed immediately toward the heavily forested mountain slope behind him. So at least the ruins still existed and were known to the villagers of Suluca.

The elderly man climbed into the taxi and guided us to the start of an unmade track that marked the beginning of a very bumpy ride in a vehicle that was scarcely suitable for such a journey. As we climbed higher and higher, generally with the steep hillside to our left, we rose above the surrounding landscape, which stretched away to the north, and for the first time I got a glimpse of the Murad Şu, or Eastern Euphrates, winding its way across the plain of Mush.

PKK SITUATION

I did inquire about the situation with the PKK locally and was informed that the mountains were under rebel control, so much so that Turkish forces did not even venture into the area unless it was part of an official military offensive. I asked also about the chances of getting to Bingöl Mountain and was told that this area was currently an active front line and thus a no-go zone to visitors like me. This was a massive disappointment, but for the moment my principal goal was to get to Yeghrdut.

After driving for around fifteen to twenty minutes, we leveled out but still faced the prospect of an even higher climb to the east of our position. The taxi driver seemed lost, the guide and his friend didn’t know what to do, and no one was around to ask for directions. My map seemed useless, so the only option left was to stand on a high spot and just look for any sign of ruins.

It was the guide’s friend who first spotted Dera Sor. Over on a ridge, about half a mile away, was what appeared to be a long, red wall on a flat ridge. That had to be it, and without further ado we were back in the taxi trying to reach the spot. The path seemed strewn with potholes, so we left the vehicle in the capable hands of the guide’s friend and continued on foot in the baking hot sun.

The track lifted up over an incline, beyond which on the left was a ridge of pine trees. I was struck immediately by the extreme redness of the earth, created no doubt by sandstone with a heavy iron oxide content that had long since crumbled to dust. To the right the ground sloped away toward the plain below. Scrub and a few clumps of trees grew here and there, but generally the land seemed parched and dry.

THE DERA SOR COMMUNITY

Coming into view now was a group of large, wigwamlike tents, some covered with white tarpaulin, others with tree branches. There were also circular pens full of turkeys and plenty of goats running loose around the whole camp. People were already emerging to see what all the commotion was about. I felt that the sight of an Englishman in desert suit, straw trilby hat, and black-framed glasses was not the norm for these people. Coming out to meet us were women wearing brightly colored hijab headscarves, several small children, three young men in their late teens, and a tall, thin, elderly gentleman with large moustache, gray jacket, and traditional Turkish fez, a black one that had seen better days. He was quite clearly the leader of the small community, which numbered fifteen to twenty individuals.

These people were seasonal pastoralists, who live out on the mountainside during the summer months, then retire to more urban environments when the cold weather sets in around November. From then on until March or April, the whole region can be covered from top to bottom in thick snow, making life very difficult indeed.

Our guide greeted the fez-wearing man and his family, and conversations ensued regarding the purpose of our visit. The subject of the ruins was discussed, and from the nods and points toward a large earthen ridge of debris immediately west of the settlement, above which I could see the tops of red-stone walls, I realized that there was no obvious problem with our being here. Yet before going any further I asked the elderly man about the monastery’s sacred tree and holy spring. Did he know where these were?

A VISIT TO THE SPRING

Exchanges between the guide and the leader resulted in our moving out into parched scrubland between the camp and the ruins. Not 40 yards (37 meters) from where we had stood was the spring, close to the base of the north-facing hill slope. From its sunken entrance, marked by an arch of large, flat stones, the leader removed a mesh of tree branches bound together with nails, and put there to prevent animals from contaminating the water. With this I sought permission to climb inside the cramped space, created by a rounded roof of stonework overlaid with earth.

I wanted to get some pictures and drink a little water, which I now saw came up into a small pool before trickling away beneath the earth. Farther down the hill the water flow reemerged from a metal pipe, creating the beginnings of the Kilise Şu stream, which flows into the Eastern Euphrates. I was now at a source of one of the four rivers of Paradise.

Despite Yeghrdut’s location on the edge of Paradise, I was dismayed to see plastic cups and containers, as well as cooking utensils and half-buried dustbin liners, strewn about inside the hollow. It was clear that the spring was no longer seen as sacred, a fact confirmed through conversations with the fez-wearing man.

THE HOLY TREE

I asked next to see the old walnut tree, which had been renowned throughout the entire province as a place of healing (see figure 39.1 on p. 346). Our hosts nodded, ushering us on another 20 yards (18 meters) to a dusty patch of ground. Here they pointed toward the remains of an old tree stump still in situ, with a girth of around 5 feet (1.5 meters). Clearly, this was not the original evergreen tree that had stood on the spot in Thaddeus’s day, but it was certainly a potent symbol of its former presence here.

Figure 39.1. Dera Sor, the ruins of the Yeghrdut monastery, in snow, from a Google Earth image taken on April 1, 2009. Note the walnut tree, the final incarnation of the “evergreen tree,” under which the disciple Thaddeus apparently deposited a piece of the Tree of Life and the container that held the essence of holy oil used to anoint “prophets and apostles.” Courtesy of DigitalGlobe 2013.

When I inquired about what had happened to the tree, I was told that it had fallen down around two years earlier, and that two trucks were needed to carry away all the timber. Hearing this made me incredibly sad and a little annoyed that the tree had not been better preserved, especially given that it reflected nearly two thousand years of history at the site.

According to what I had found out over the past few months,2 the evergreen tree under which Thaddeus had concealed the holy relics was said to have survived to the present day, an unlikely claim particularly after examining the pitiful remains of the walnut tree. According to tradition, an eagle had nested at the summit of the original tree. A flowing stream emerged from beneath its trunk, and a stone wall, with an altar at one end, had protected its roots. Women and young ladies in particular would come here not just to rest beneath its shade but also to take water from the stream to cure ailments. They would take away any small part of the tree they could find—leaves, bark, twigs, and so forth, which would be placed inside their clothes, against the body, to relieve pain. Apparently, any greenery removed from the tree was the ultimate healing aid, with the ability to retain its healing potency forever.3

I learned also that the fragment of the Tree of Life deposited at Yeghrdut by Thaddeus was the subject of a quite extraordinary legend.4 One day a shepherd visiting the monastery saw the simple box containing the relic and decided to steal it, thinking that its contents might be worth money. He got home and decided to take a look at what was inside. Yet on seeing that it contained a piece of wood, the man panicked and threw the box on the fire. No sooner had he done this than flames burst forth from the hearth and consumed the entire house, sending the shepherd running for his life.

Prompted by the fire, the great eagle that guarded the holy tree then swooped down and snatched up the box with its precious contents, neither of which had been damaged in any way. The bird took them back to its nest and thereafter became their constant guardian, never letting anyone with ill intent near them.

EAGLE ON THE WORLD TREE

This legend, which seems like something out of a book of Turkish folktales, was believed fervently by the monks of the monastery and is included in the entry for Yeghrdut in the aforementioned encyclopedia of monasteries and churches of the Taron Province.5 Whatever its reality, the story oozes mythological symbolism. The eagle sitting atop the tree guarding a piece of the Tree of Life is suggestive of the world tree Yggdrasil in Norse tradition, which also has an eagle nesting on its summit.

The similarity between the name Yeghrdut and Yggdrasil is probably coincidental, although it has not stopped people from drawing comparisons between yggdr, one possible root behind the name Yeghrdut, and Yggdrasil, and also between Hızır, or al-Khidr, a guardian of the Waters of Life, and Odin, the god who hangs on the Norse world tree to gain the knowledge of the runic alphabet.6 Interestingly, compelling evidence indicates that the origins of some Norse mythology, and perhaps even the roots of the Scandinavian people, are to be looked for in the region around Lake Van. World-renowned explorer Thor Heyerdahl (1914–2002) was working on these theories shortly before his death.7 The exact derivation of the word Yeghrdut still remains unclear, as it is not a proper Armenian word, although it does seem to relate to Armenian word roots meaning “king,” “flower,” and “willow,”8 or, as I had already established, shuyugho, the “young branch of the (oil tree).”9

The eagle itself was the symbol of the ancient kingdom of Taron, which was established in the fourth century AD by an Armenian dynasty of kings called the Mamikonians, whose emblem was the double-headed eagle. This connection between Taron and the eagle might easily have stemmed from the existence of a pagan god in the form of an eagle that was venerated in Armenia Major during former ages. The association between the eagle of Yeghrdut and the holy tree, however, might well stem from a source much closer to the root of the mystery.

THE WOOD THAT CUTS

There are many different variations of the story of how the Holy Wood or Holy Timber of Life used to create the Cross of Calvary, which originated in some manner from the Tree of Life. One version has Adam being given a branch upon his departure from the Garden of Eden; in another it is handed to Seth in the form of seeds or saplings; and in still another a bird known as the roc, a gigantic, mythical eagle of Arabic tradition, picks up “a piece of wood from one of the trees in the garden.”10 This mythical bird carries the branch to Jerusalem and there drops it onto a huge, upside-down copper cauldron, beneath which is the bird’s young. They are being held captive by King Solomon, who has snatched them away from their mother after searching for guidance from God as to how he might go about finishing the temple begun by his father, David.

The weight of the wood smashes the cauldron, releasing the bird’s young. Thereafter, Solomon realizes that the wood left by the roc can miraculously cut stone blocks, enabling the king to complete the temple. Following a long story involving King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, the Holy Wood finds its way to the carpenter’s shop, where, as in the more traditional story, it is fashioned into the cross on which Christ is crucified.11

The important part of this story is that this piece of wood taken from “one of the trees in the garden,” an allusion unquestionably to the Tree of Life, is linked with an eaglelike bird, just as it is in the Yeghrdut legend. This lends support to the belief that the monastery had in its possession a fragment of the Holy Wood of Life thought to derive from the Tree of Life itself.

THE RUINS EXPLORED

After asking for and getting a few small fragments of the remaining tree trunk (as well as a walnut shell, confirming it as the holy tree mentioned in the correspondence with the contact from Kızılağaç), we now moved on to the goal of the expedition—the monastery itself. Walking about 40 yards (37 meters) we now climbed a huge pile of rubble and debris and saw spread out before us the ruins in all their glory. The raised mound marked the position of the structure’s eastern wall, while similar piles of rubble marked the location of the north and south walls. However, in the west, the remaining wall, made up of a thick base of rust-red bricks and an upper level of lighter-colored gray stone, was substantial, being as much as 15 feet (4.5 meters) in height, with a large breach toward its northern end.

In all, the west wall was around 70 yards (64 meters) in length, with a returning wall at its southern end, which quickly reduces down to ground level. Walking up to the remaining wall, I noticed a series of linear foundations jutting out at right angles, which I suspected marked the position of small cells, most likely living quarters for the monks. It is incredible to think that this immense structure was, apparently, two stories high and almost equal in size to the more famous monastery of Surb Karapet, located in the foothills of the Armenian Highlands on the opposite side of the plain of Mush (indeed, the monasteries, both dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, would each have been visible to the other).

FINDING THE CHURCHES

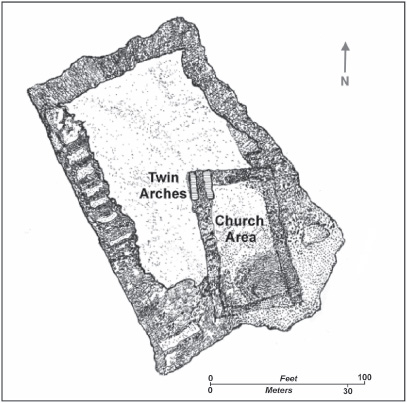

The only other architectural features that remain standing at the monastery site are two beautiful stones arches, around 12 feet (3.7 meters) high, one positioned directly in front of the other (see figure 39.2 on p. 350). These are oriented east-northeast (at approximately 20 degrees north of east) and once formed the northern entrance into a large building located in the southeast quadrant of the monastery. All around the arches are piles of rubble and debris, reducing their interior height, although it is still possible to pass beneath them fairly comfortably.

Figure 39.2. Plan of Dera Sor, the ruins of the Yeghrdut monastery, drawn by the author following his return from the site in September 2012. Note the different alignment of the building structure contained within the southeast quadrant of the perimeter wall, suggesting that it might belong to a different age.

The identity of the ruins attached to the twin arches has been impossible to establish with any degree of certainty, as no surviving photographs or plans of the monastery have been found.12 Present somewhere in the monastery’s southeast quadrant was a large, domed church dedicated to the Mother of God. Attached to it was a chapel of Saint John the Baptist in which was a martyrium where the saint’s relics were kept. Here too was another chapel dedicated to Gregory the Illuminator, located beyond the church’s northwest corner. Its position was marked by an imposing bell tower, under which was a walkway into the main church, the walls of which were constructed of stone in three different colors—black, yellow, and reddish brown. Apparently, the bell tower collapsed during an earthquake in 1866, a portent perhaps of the imminent destruction of the monastery and the disappearance of its monks at the time of the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Exactly what happened here at Yeghrdut may never be known, but it is unlikely to have been pleasant, and as for the fate of the monastery’s precious relics, no one can say. Those Armenians who remain today in Mush have adopted a radical form of Islam, so it is unlikely that any real answers will be forthcoming any time soon.

I was pretty sure that the bell tower was located somewhere in the vicinity of the stone arches; indeed, they might easily have formed its support columns, under which one passed to enter the main church. In my dream the monks had conducted the strange ritual involving the elevation of the fragment of the Tree of Life at the center of the church. So I now stood the closest I was going to get to that very spot, which was a strange sensation, especially after traveling nearly 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) to be there.

SPECTACULAR VIEWS

As I moved across to the piles of debris marking the north wall, I realized just how spectacular the view was from this elevated position; to say it was impressive would be an understatement. The monastery, as I knew only too well, looked out across the plain of Mush and the Eastern Euphrates, beyond which were the foothills and peaks of the Armenian Highlands. Yet the monastery itself is sheltered beneath hilly slopes to the southeast, south, and west, which would have afforded it some degree of protection from the elements during the long, harsh winters.

For an hour or so, I followed the course of the perimeter wall, obtaining photos, getting video footage, and taking in the ambience, always with one of our hosts by my side. Scattered everywhere were potsherds of all shapes and sizes, which I could see embraced a time frame from medieval times right down to the modern day. However, I was not concerned with ceramics on this occasion. I wanted to find evidence that the site had been occupied prior to the arrival of Christianity in the fourth century. Yet, in all honesty, I found nothing of interest, even though there was every possibility that a settlement from a former age could have occupied a position higher up the hill, closer to its summit perhaps.

One legend fervently believed by the monks of Yeghrdut tells how near “a small workshop” somewhere beyond the monastery, a concealed copy of the “Old Testament” was found. It was apparently seen as a gift of the eagle, presumably the one that lived in the holy evergreen tree.13 The implication of this chance discovery is that the book belonged to an age that antedated the monastery, implying that the site was important even before the arrival of Gregory the Illuminator in the fourth century.

IS THIS EDEN?

It was very difficult to take in the setting during this one brief visit. My sense, however, was that the monastery had been deliberately left to fall into decay. The site had been neglected, this was clear, and no one really seemed interested in its history or preservation. It was difficult to come to terms with the fact that until 1915 Yeghrdut had been a thriving monastery, as well as a tranquil place of healing for Armenians and Kurds alike. Men and women came here not just to cure ailments but also to rejuvenate both body and soul. There was a natural vitality about this site, which people believed was channeled through the holy tree and spring, the reason they took away leaves, twigs, and bark, not to mention the holy water itself.

All that is now gone. All that remains is the tranquillity of the site and its extraordinary setting, which is simply outstanding. This was the sight the monks of Yeghrdut woke up to every morning, making it easy to understand why they might have believed this was some quiet corner on the edge of Eden itself.

THE RED EARTH OF ADAM

The monks also cannot have failed to notice the absolute redness of the earth, especially the hill slope to the southeast of the monastery. It would have reminded them that the first-century Jewish scholar Flavius Josephus wrote that Adam was created out of red clay:

That God took dust from the ground, and formed man, and inserted in him a spirit and a soul. This man was called Adam, which in the Hebrew tongue signifies one that is red, because he was formed out of red earth, compounded together; for of that kind is virgin and true earth.14

Another tradition said that after Adam’s death, he was buried by angels “in the spot where God found the dust” to fashion his body.15 So if the monks did see the red earth surrounding the monastery as significant (and it is rarely glimpsed anywhere else in the area), then it might well have strengthened the conviction that their monastery existed close to the site where Adam and Eve lived after their expulsion from Paradise, and where afterward their son Seth and his descendants continued to live right down to the time of the flood.

A RESPITE

After completing our visit to the ruins, the elderly man and his wife opened up their home to us. Inside the large, conical tent, its opening directed toward the plain below, we sat down on a bed of brightly patterned kilim rugs that overlaid a bed of flat stone slabs. Placed in front of us was an enormous silver platter containing glasses of sweet tea and bowls of local food, including yogurt, Turkish flat bread, and salad. The kindness of these people was overwhelming, particularly as they did not know me, our guide, or the taxi driver, who were all afforded the same degree of hospitality.

I then learned something important from the fez-wearing man. He told me that somewhere on the hill slope, immediately behind the monastery’s west wall, there was once a large cave opening. Yet it had vanished after the “rich” Armenian monks had stuffed it full of “gold” prior to their rapid departure. Local people had attempted to find the cave entrance in order to reach the “gold,” but so far all efforts had come to nothing.

I found the story difficult to believe, first, because there was no sign of any cave existing today (I checked afterward), and, second, the fervent belief that Armenian monks were so rich that they simply could not carry away all their cumbersome gold treasure was quite simply fantasy. The only thing it did do was remind me of the legends regarding the Cave of Treasures, where Adam, Eve, Seth, and their family had lived and where they were supposedly buried upon their deaths. Was the role model for the Cave of Treasures around here somewhere, if not close to the monastery, then in the foothills of the mountains immediately to the south of Yeghrdut? Was it there that the secrets of Adam, inscribed either on steles or pillars, would one day be found? Or was it north of the plain of Mush, somewhere in the vicinity of Bingöl Mountain? There were no hard and fast answers, and for now the matter would have to rest there.

One other piece of information I picked up was that around fifteen years before, workmen had arrived one day and broken down whole sections of the monastery’s remaining walls, with the resulting piles of rubble being carried away in waiting trucks. Hearing this instantly made me concerned about the fate of the remaining ruins, which are not protected in any manner, and so could, presumably, be destroyed at any time.

Shortly after that it was time to leave. A thunderstorm was close by, and once it hit, any resulting flash floods could make driving back down the mountainside treacherous. So as the taxi now began to make its descent, I watched awestruck as a rolling gray cloud came in from the west and seemed to follow the course of the Euphrates, sending out lightning flashes that struck the plain of Mush and even the waters of the river itself. No wonder the Semitic peoples of Syria and Canaan came to believe that the abode of the god El was to be found in this otherworldly Land of Darkness.

AN UNEXPECTED JOURNEY

That night and the next day I recorded my thoughts and impressions about the trip to the monastery. There was a sense that I had achieved what I had come here to do, but I wanted to go back one more time, and this I managed to do on Wednesday, September 12, with the same taxi driver, although this time with a new guide, a social worker named Idris, who spoke perfect English. He knew every village, large and small, on the plain of Mush, as he visits them as part of his day-to-day job. We shared a mutual passion for keeping alive the rich cultural heritage of the region and so very quickly became friends.

The following day Idris asked if I would like to accompany him the next day to a village called Muska, not far from Bingöl Mountain. He had friends there who were Alevi and thought this might be an ideal opportunity for me to speak with them about their beliefs and practices. Even though I was due to leave Mush early the morning after that, this was too good an opportunity to miss, so I said yes.

I asked Idris about the situation regarding access to Bingöl Mountain, as I understood it was a virtual no-go area because of the recent army offensives. He said we would be fine and that if we did encounter any PKK units in the hills, he knew what to say (Kurdish sympathy among the local population runs very high indeed). With that, I accepted finally that I might get to glimpse Bingöl Mountain, at least from a distance, which is something I had almost abandoned any thought of achieving on this journey of discovery.