THESE notes on Shakespeare are written with a proper sense of humility and awe. They do not profess to be anything more than a series of notes, — and they deal, often, with technical matters.

In these gigantic works there are the differences in nature, in matter, in light, in darkness, in movement, that we find in the universe. Sometimes the identities of which this world is made belong, as it were, to the separate kingdoms, to the different grades in the series of existence, — to the mineral kingdom, the vegetable kingdom, the brute creation. — Or they are three of the elements: Fire: Lear. Water: Hamlet. Air: Romeo and Juliet. The fourth element is always present! Shakespeare knew that there is no fragment of clay, however little worth, that is not entirely composed of inexplicable qualities.

Characters such as Falstaff are “lumps of the world’, are still ‘alive from the roots, a part not yet cut off from universal nature’, and have ‘a gross’ physical ‘enormity of sensation’ which approaches a kind of physical godhead.

Certain characters that we do not see, but that are known to the beings of this world, — Robin Nightwork, for instance, and old Jane Nightwork (‘old, old, Master Shallow’), and Cousin Silence, whom we do see, — are like sweet shadows, remembered from youth, and still haunting the brain of that earthy old man, Sir John Falstaff, whose ‘redness is from Adam’.

Shakespeare is like the sun, that common-kissing Titan, having ‘a passion for matter, pure and impure’ —’ an energy beyond good and evil, an immense benevolence creating without choice or preference out of the need of giving birth to life. Never was there such a homage to light, to light and the principle of life.’

(NOTE.—This was said by Arthur Symons of a still great, though infinitely lesser artist than Shakespeare, and an artist in a different medium, — Edouard Manet. But it seems still more applicable to Shakespeare.)

He knew all differences in good and evil, — that between the evil of lago, who, as a devil, is Prince of the Power of the Air … who, ‘as the air works upon our bodies, this Presence works upon our minds’, — and the beings of’ Titus Andronicus’, the kind of being of whom Donne, in his 41st Sermon, said, ‘He is a devil to himself, that could be, and would be, ambitious in a spital, licentious in a wilderness, voluptuous in a famine, and abound with temptations in himself, though there were no devil’. — (This is not one of the greatest of Shakespeare’s plays, but has, as Swinburne said of Chapman,’ passages of a sublime and Titanic beauty, rebellious and excessive in style as in sentiment, but full of majestic and massive harmony’.)

In the tragedies the theme is, in nearly all cases, the struggle of man against the gigantic forces of nature, or of man brought face to face with the eternal truths…. The king made equal with the beggar at the feast of the worm. The king whose will has never been combated, under ‘the extremities of the skies’, the king who

Striues in his little world of man to outscorne

The to-and-fro conflicting wind and raine, —

(‘when the raine came to wet me once and the wind to make me chatter, when the Thunder would not peace at my bidding, there I found’em, there I smelt’em out. Go to, they are not men o’ their words: they told me I was euerything:’tis a Lye: I am not Agu-proofe’)…. Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, hunted through the days and nights by the Furies their crime has summoned from the depths … those Furies who pull down days and nights upon them until light is as darkness, darkness as light:

MACBETH: … What is the night?

LADY MACBETH: Almost at odds with morning, which is which.

Death quenching the light of beauty and of youth, quenching love:

The iawes of darknesse do deuoure it up

So quick bright things come to confusion.

Timon of Athens digging with his nails in the wilderness to unearth the most humble roots wherewith to stay his hunger, and finding, not roots, but uneatable gold, — Hamlet and that terrible’ globe’ his head, that world ruled by so small a star.

King Lear is largely a diatribe against procreation…. Edgar’s

The Gods are just, and of our pleasant uices

Make instruments to plague us:

The dark and uitious place where thee he got

Cost him his eyes.

Gloucester to Lear:

… Dost thou know me?

Lear, replying to the eyeless Gloucester:

I remember thine eyes well enough. Dost thou squinny at me? No, doe thy worst, blind Cupid; Ile not loue.

Lear crying

No, they cannot touch me for coyning:

I am the King himselfe …

— the coyning to which he refers is, I think, the procreation of his daughters, that base metal.

Yet Man can rise to such a height that he can speak, as an equal, with the gods:

KENT: Fortune, good night, smile once more, turn thy wheel.

The griefs, the joys, of these vast beings are as those of the elements, of the universe or the heavens.

Will Caesar weepe?

He has a cloud in’s face.

(Antony and Cleopatra, III, 2)

Her brother’s noontide with th’ Antipodes.

(Midsummer Nighfs Dream, III, 2)

Man speaks with the gods, and the answer of the gods sounds through strange mouths … the voice of the Oracle speaks through the lips of two passers-by in the marketplace:

‘’Tis uerie like he hath the Falling sicknesse.’

‘No, Cesar hath it not: but you, and I

And honest Caska, we haue the Falling sicknesse.’

‘I know not what you meane by that, but I am sure Cesar fell doune. If the rag-tagge people did not clap him, and hisse him, according as he pleas’d, and displeas’d them, as they use to do the players in the theatre, I am no true man.’

The voice of the Oracle sounds again through the lips of Macbeth’s porter. As the knocking at the Castle gate changes to the noise of the damned knocking at the gate of Hell, so that voice changes to that of the porter at Hell’s gate, — the Castle is no longer a Castle, but the place of the damned, of that ‘Farmer that hang’d himselfe on th’ expectation of Plentie’ — (the woman to whom the harvest was of the physical world, — who sowed, who reaped and who, in the end, hanged herself when the reaping was done, and she knew the worth of the harvest) — and the man ‘who committed Treason enough for God’s sake, yet could not equivocate to Heaven: O! come in, Equivocator’. Throughout the tragedies there are strange mutterings, as of a sibyl prophesying doom:

‘There was such laughing. Queen Hecuba laught till her eyes ran ore.’

‘… with Milstones.’

‘And Cassandra laught.’

Or a ghost turns prophet:

BRUTUS

Why com’st thou?

GHOST

To tell thee thou shalt see me at Philippi.

BRUTUS

Well, then I shall see thee againe?

I, at Philippi.

BRUTUS

Why, I will see thee at Philippi then.

And from the lips of another ghost sound these words:

And duller should’st thou be than the fat weede

That rots itselfe in ease on Lethe Wharfe.

• • • • • •

The beating of these greater hearts, the pulse of this vaster humanity, seem energised by these rhythms, which are like the ‘active principles’ of which Newton wrote.

Shakespeare’s own immense benevolence and love, and the tragedy, the doom which are shadows cast by these huge characters, — (shadows bearing their shape, moving as they act) are conveyed through the world of sound. Through rhythm, which is’ the mind of dance and the skeleton of tone’, and through tone, ‘which is the heart of man’,—‘this organic being clothed with the flesh of the world’.

At moments, in the very sound of the verse or the prose, is heard the tread of Doom. The beating of Mac-beth’s heart changes, suddenly, to the knock of Fate’s hand upon the door, in that passage already quoted above, where the porter hears the damned knocking at the gate of Hell.

PORTER: ‘Heere’s a knocking indeede! If a man were Porter of Hell-gate he should have olde turning the key. Knock, knock, knock…. But this is too cold for Hell.’

(And why is it too cold for Hell? Because of the coldness of the will that planned the deed? Because the upper circles of Hell are warmed by some human passion, and the Porter knew nothing, as yet, of the nethermost darkness.) Or was it not the tread of Doom, the knocking of the damned souls, that was heard, — but (as Sir Arthur Quiller Couch suggested in Shakespeare’s Workmanship,1 ‘the sane, clear, broad, ordinary workaday world asserting itself, and none the more relentingly for being workaday, and common and ordinary, and broad, clean and sane’.

If we consider the celestial and terrestrial mechanics of Shakespeare’s vast music, at times the movement of the lines is like that slow astronomic rhythm by which the northern and southern atmospheres are alternately subject to greater extremes of temperature. So it is, I think, with Othello. Sometimes the verse is frozen into an eternal polar night, as in certain passages of Macbeth. Or it has a million varieties of heat and of attraction. Sometimes it is like the sun’s heat, as in Antony and Cleopatra; sometimes it is the still-retained heat of the earth, as in Henry IV and Henry V. It moves, like Saturn, in the Dorian mode, like Jupiter in the Phrygian.

Sometimes the gigantic phrases, thrown up by passion, have the character of those geological phenomena, brought about in the lapse of cosmical time, by the sun’s heat, by the retained internal heat of the earth, — or seem part of the earth, fulgurites, rocky substances fused or vitrified by lightning, — as in Timon of Athens, — or, as in Lear, the words seem thunderbolts, hurled from the heart of heaven. Lear, Timon of Athens, seem the works of a god who is compact of earth and fire, or of whom it might be said that he is a fifth element.

The immense differences in shape and character between the caesuras in his verse, and between the pauses that end the lines, have much to do with the variation.

Sometimes the pause is like a whirlpool or vortex, as in the first line of Othello’s

Excellent wretch! Perdition catch my soul,

But I do love thee! And when I love thee not

Chaos is come again.

Here, between ‘wretch!’ and ‘Perdition’, the Caesura has a swirling movement.

But the most wonderful caesura of all occurs in Macbeth, as we shall see.

The events in the life of a character, as well as the personality, the very appearance of Shakespeare’s men and women, are suggested by the texture, the movement of the lines. In Macbeth, for instance, we find, over and over again, schemes of tuneless dropping dissonances. Take the opening of the play:

FIRST WITCH.

When shall we three meet againe?

In thunder, lightning or in raine?

SECOND WITCH

When the hurly-burly’s done,

When the battle’s lost and won.

THIRD WITCH

That will be ere set of Sun.

FIRST WITCH

Where the place?

SECOND WITCH

Upon the heath.

THIRD WITCH

There to meet with Macbeth.

‘Done’ is a dropping dissonance to ‘raine’, ‘heath’ to the second syllable of ‘Macbeth’, — and these untuned dissonances, falling from the mouths of the three Fates degraded into the shape of filthy hags, have significance. In this vast world torn from the universe of eternal night, there are three tragic themes. The first theme is that of the actual guilt, and the separation in damnation of the two characters, — of the man who, in spite of his guilt, walks the road of the spirit, and who loves the light he has forsaken, — of the woman who, after that invocation to the ‘Spirits who tend on mortall thoughts’, walks in the material world, and who does not know that light exists, until she is nearing the end and must seek the comfort of one small taper to illumine all the murkiness of Hell. That small taper is the light of her soul. The second tragic theme is of the man’s love for this woman whose damnation is of the earth and who is unable, therefore, to conceive of the damnation of the spirit, — and who, in her blindness, strays away from him, leaving him for ever to his lonely hell. The third tragic theme is the woman’s despairing love for the man whose vision she cannot see, and whom she has helped to drive into damnation.

The very voices of these two damned souls have therefore a different sound. His voice is that of some gigantic being in torment, — of a lion with a human soul. In her speech invoking darkness, the actual sound is so murky and thick that the lines seem impervious to light, and, at times rusty, as though they had lain in the blood that had been spilt, or in some hell-borne dew.

There is no escape from what we have done. The past will return to confront us. And even that is shown in the verse. In that invocation there are perpetual echoes, sometimes far removed from each other, sometimes placed close together.

For instance, in the line

And fill me from the Crowne to the Toe, top-full,

‘full’ is a darkened dissonance to ‘fill’ — and these dissonances, put at opposite ends of the line — together with the particular placing of the alliterative f’s of ‘fill’ and ‘full’, and the alliterative t’s— and the rocking up and down of the dissonantal o’s (‘Crowne’, ‘Toe’, ‘top’) — show us a mind reeling on the brink of madness, about to topple down into those depths, yet striving to retain its balance.

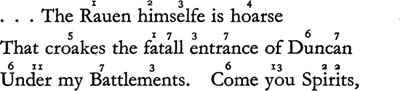

Let us examine the passage for a moment. I have numbered the stressed assonances because the manner in which they are placed is largely responsible for the movement, and because the texture is extremely variable, — murky always, excepting for a few flares from the fires of Hell, but varying in the thickness of that murk.

Throughout the whole of the speech, an untuned and terrible effect is produced by these discordant dissonantal o’s used outwardly and inwardly in the lines, —‘hoarse’ rising to ‘croakes’, thickening to ‘come’, darkening to ‘mortall thoughts’ and then — supreme example, making the line rock up and down, and finally topple over, in

And fill me from the Crowne to the Toe, top-full.

‘Blood’, ‘Stop’, ‘Remorse’, ‘Come’, each of these dissonantal o’s has a different height or depth, a different length or choked shortness.

There is a fabric, too, of dull and rusty vowels, thickened m’s and p’s, and of unshaping s’s, — these latter are un-shaping because they are placed close together, and so deprive the line of form, to some degree, as in

Stop up th’ access and passage to Remorse

That no compunctious uisitings of Nature

or

Where-euer, in your sightlesse substances

Throughout the passage, the consonants are for ever thickening and then thinning again, — perhaps as the will hardens and then, momentarily, dissolves. In the lines

That croakes the fatall entrance of Duncan

Under my Battlements. Come you Spirits.

‘Come’ is a thickened assonance to the Dun of ‘Duncan’ and of the first syllable of ‘under’. And in the line

That no compunctious uisitings of Nature

the first syllable of ‘compunctious’ is a sort of darkened, thickened reverberation of the word ‘come’ (darkened or thickened because what follows throws a shade backward); the second syllable is a thickened echo of the first syllable of ‘Duncan’.

As the giant shuttles of Fate weave, closening and opening, so do the lines of this speech seem to close and open, and to change their length. But this change is in appearance only, and not real. By this I mean, there are no extra syllables to the line. The apparent change is due to the brightening and lengthening of the vowel sounds. For though, as I have said already, the words are frequently dull and rusty in this passage, at times they rise to a harsh shriek, which sometimes is sustained, sometimes broken, — as with those broken echoes ‘Raven’, ‘fatall’.

There are moments, too, when the line is prolonged for other reasons than that of the changing vowel lengths:

And take my Milke for Gall, you murth’ring Ministers

is an example. Here, in spite of the fact that all the vowels are dulled (with the exception of the high a of ‘take’ and the dark a of ‘Gall’), the l’s prolong the line slightly, the thick muffled reverberations of the alliterative m’s, placed so close together, produce a peculiar effect of dulled horror.

Stop up th’ access and passage to Remorse,

we shall find that instead of the line being slowed (and therefore, in appearance, lengthened) by the s’s the dull assonantal a’s, a more powerful factor, when placed close together, actually shorten the line, which, again, is thickened by the p’s ending words that are placed side by side. The effect produced on a line by p’s ending a word, and p’s beginning a word, is completely different. A p beginning a word does not necessarily thicken the line.

Sometimes the particular placing of the assonances produces a sound like that of a fevered, uneven pulse, — an example is the effect brought about by the drumming of the dull Un … om sounds in the lines

Duncan

Under my Battlements. Come …

This terrible drumming sound is heard over and over again throughout the passage, and is due not only to the placing of the assonances, but also to the particular placing of double-syllabled and — (this has a still stronger effect) — treble-syllabled words and quick-moving unaccented one-syllabled words. In the line

And fill me from the Crowne to the Toe, top-full,

‘to the’ is an example of the effect of these quick-moving unaccented one-syllabled words.

That no compunctious uisitings of Nature

is an example of the use of three-syllabled words, disturbing (purposely) the movement of the line.

This march towards Hell is slow, and has a thunderous darkened pomp. It is slow, and yet it has but few pauses, — (for that march is of her own will, she is driven by that will, as by a Fury), — and those pauses are not long, but deep, like fissures opening down into Hell. There is, however, a stretching pause, after the word ‘Gall’.

The speeches of Macbeth have a different sound from this. He, at least, would retreat from the path. His dark and terrible voice is not covered by a blood-dewed rust, is not like a black and impenetrable smoke from Hell, as is the voice of the woman who, to him, is Fate, — it is hollow like the depths into which he has fallen, it returns ever, though it, too, has discordances, to one note, dark as the Hell through which he walks with that sleepless soul. The sound is ever: ‘No more. Cawdor shall sleep no more, Macbeth shall sleep no more’.

Dr. A. C. Bradley, in his Shakespearean Tragedy1 calls our attention to the three beings in one who must suffer that damnation. ‘What he’ (Macbeth) ‘heard was the voice that first cried “Macbeth does murther sleepe”, — and then, a minute later, with a change of tense, denounced on him, as if his three names gave him three personalities to suffer in the doom of sleeplessness:

Glamis hath murihered Sleepe, and therefore Cawdor

Shall sleepe no more, Macbeth shall sleepe no more.’

The despair of Macbeth, hearing the voice that cries those words, his sense that there is no escape, is brought home to us by the dark, hollow, ever-recurrent echoes of the or … aw sounds. That is the keynote of the whole speech. As with Lady Macbeth’s speech, the magnificence of the rhythm is largely controlled by the particular places in which the alliterations and assonances are placed — (though in the two speeches they are used completely differently, and have an utterly different effect).

MACBETH

Me thought I heard a voyce cry ‘Sleepe no more.

Macbeth does murther Sleepe.’ the innocent Sleepe,

Sleepe, that knits up the rauel’d Sleave of Care,

The death of each Daye’s life, sore Labor’s Bath,

Balme of hurt mindes, great Nature’s second Course,

Chief Nourisher in Life’s Feast, —

LADY MACBETH

What doe you meane?

MACBETH

Still it cry’d ‘Sleepe no more!’ to all the House:

‘Glamis hath murther’d Sleepe, and therefore Cawdor

Shall sleepe no more, Macbeth shall sleepe no more!’

Twice, a word shudders in that dark voice. The first time it is the word ‘innocent’ — that word which must henceforth fly from the voice that uttered it.

Sometimes an awe-inspiring, drum-beating sound is heard; — once it is slow, and is caused by placing alliterative b’s, with near-assonantal vowel sounds,—‘Bath’, ‘Balme’ — at the end of one line and the beginning of the next. (There is a strong pause between these words.) The reason why these a’s are not an exact assonance is because of the differences in thickness between the th and the Im. Then, for a second time, two a sounds are placed close together, ‘great Nature’s’, and here the beat is less emphatic; there is no pause between the sounds.

But above all, the quickened beat of a terror-stricken heart is heard in ‘therefore Cawdor’ (‘fore’ being a darkened dissonance to ‘there’, and the two other syllables being as nearly as possible assonances to ‘fore’, — though ‘Caw’ is in a slight degree less dark). This is followed by the long, stately, and inexorable march of Doom:

Shall sleepe no more, Macbeth shall sleepe no more.

It is in this scene that we first become aware of the different paths of damnation, — the path of the spirit that sees that not all great Neptune’s Ocean will wash the blood clean from his hand, — and that of the earth-bound Fate who, until she is near her end, dreams that ‘a little water cleares us of this deed’, and who, when the voice cries

Cawdor

Shall sleepe no more, Macbeth shall sleepe no more,

hears only the small voice of the cricket, — or a dark, but still human voice.

MACBETH

I have done the deed. Didst thou not hear a noyse?

LADY MACBETH

I heard the Owle schreame, and the Crickets cry.

Did not you speake?

MACBETH

When?

LADY MACBETH

Now.

MACBETH

As I descended?

Aye.

MACBETH

Hearke.

Who lyes i’ the second chamber?

LADY MACBETH

Donalbaine.

From now onward, only blood, and the road that he must tread, exist for Macbeth in the physical world:

Who lyes i’ the second chamber?

— who must be the next to fall under his blood-stained hands, upon that road? … But to Lady Macbeth, he is speaking, not of a grave that must be dug, and of a man about to die, but of one sleeping in his bed, — Donalbaine.

Here then, in those few lines, these two guilt-stricken souls say farewell for ever. The immense pause after Lady Macbeth’s ‘Aye’ is a gap in time, like the immense gap between the Ice Age and the Stone Age, wherein, as science tells us, ‘the previously existing inhabitants of the earth are almost wholly destroyed, and a different class of inhabitants created’. — On the other side of that gap in time, Macbeth rises as the new inhabitant of a changed world, — and alone in the universe of eternal night, although the voice of Lady Macbeth, his Fate, that loving Fury, still drives him onward.

Here we have one gigantic use of the pause. Before the words that follow Lady Macbeth’s’ Donalbaine’ —

MACBETH (looking at his hands)

This is a sorry sight,

the four beats falling upon the silence until Macbeth speaks, seem like the sound of blood dripping, slowly, from those hands:

What Hands are here! Hah! they plucke out mine Eyes.

Those hands are the hands of murder. They are no longer the hands of the living man who was once Macbeth, — hands made to caress with, hands made to open windows

on to the sun and air, hands made to lift the life-giving food to the mouth. Those hands have now given him darkness for ever, — a darkness surrounded by a terrible and all-seeing light, that knows every action, and that yet has no part in him.

Let us take the scene where the ghost of Banquo returns for the second time, to confront his murderer:

MACBETH

Auaunt! and quit my sight! Let the earth hide thee!

Thy bones are marrowless, thy blood is cold;

Thou hast no speculation in those eyes

Which thou dost glare with.

LADY MACBETH

Think of this, good peers,

But as a thing of custom:’tis no other;

Only it spoils the pleasure of the time.

MACBETH

What man dare, I dare:

Approach thou like the rugged Russian bear,

The arm’d rhinoceros or the Hyrcan tyger;

Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves

Shall never tremble: or be alive again,

And dare me to the desert with thy sword;

If trembling I inhabit then, protest me

The baby of a girl. Hence, horrible shadow!

Unreal mockery, hence! — Why, so, being gone,

I am a man againe. Pray you, sit still.

In these lines we hear again that terror-maddened drum-beating of a heart — produced, as before, by the varying use of alliteration, of assonances and near-assonances placed close together within the lines: ‘firm nerves’, ‘never tremble’, ‘rugged Russian’, ‘Take any shape’. The feeling of unendurably tautened, sharpened nerves is produced by the particular use of vowels that are tuned just above the pitch of almost identical vowels in the preceding word: ‘Hyrcan tyger’, for instance. The change from ‘firm nerves’ to the higher discordances of ‘Hyrcan tyger’, is another example. ‘Sight’ is a rising dissonance to ‘quit’ — rising as terror rises. ‘Hide’ is an assonance to ‘sight’, but is longer, because of the d.

Further on in the passage there are the dissonances ‘girl’, ‘unreal’ — (the latter being, as it were, a broken crumbling shadow of the sound of ‘girl’) — and the rising dissonances ‘gone’, ‘againe’. All these general discordances add to the impression of a nature alternately sharpened and untuned by fear.

Internally and externally in the lines there are far-separated, but still insistent, echoes, and these help, in part, to keep the slow sound together: ‘glare’, ‘dare’, ‘bear’ — with Lady Macbeth’s less-long, discordant, lower ‘peers’.

In the last line:

I am a man againe. Pray you, sit still,

there is practically no shape, excepting that given by the caesura, which is a chasm dividing the line. The doom-haunted man has lost even the sound of his own heart-beat.

After this scene, the gulf separating these two giant beings is impassable. Not only the change of the world in which they live, but the whole depth of the soul, separate them. They are divided in all but love. From that time, I think even the appearance of Macbeth must have inspired terror, as if he were no longer a mortal man, but one of those giant comets whom Pliny named Crinatae, ‘shaggy with bloody locks … having the appearance of a fleece surmounted with a kind of crown, — or one that prognosticates high winds and great heat … they are also visible in the winter months and about the South Pole, but they have no rays proceeding from them’.

And Lady Macbeth, — how changed is she, in that pitiful scene when she, who had cried to ‘thicke Night’ to envelop the world and her, she who had rejected light, seeks the comfort of one little taper, — the small candle-flame of her soul, to light all the murkiness of Hell. Yet still, in the lonely mutterings of one who must walk through Hell alone, save for the phantom of Macbeth, we hear that indomitable will that pushed him to his doom, rising once more in the vain hope that she may shield and guide him.

There is, in these two beings, the giant faithfulness of the Lion and his mate.

To speak of this scene from a technical point of view, the extremely interesting theory was propounded by Mr. A. M. Bayfield (A Study of Shakespeare’s Versification: Cambridge University Press) that ‘Lady Macbeth’s speeches, which have always been printed as prose, are really verse, and very fine verse too. The reader’ (he continues) ‘will see how enormously they gain by being delivered in measure, and that the lines drawn out in monosyllabic feet are as wonderfully effective as any that Shakespeare wrote.

‘But for the retention of the iambic scheme, the recognition would doubtless have been made long ago, but editors recognise no monosyllabic foot and would hesitate to produce lines with initial trochees.’

The speeches in the sleep-walking scene, if spoken as verse, have a great majesty: they drag the slow weight of the guilt along as if it were the train of pomp. But they have not the infinite pathos of the speeches when they are in prose, they do not inspire the same pity for this vast being, her gigantic will relaxed by sleep, trying to draw that will together as she wanders through the scenes of her crime. The more relaxed sound of the prose produces that effect. The beat of the verse should be felt, rather than heard, underlying the speeches.

Macbeth, too, has changed. That change came when he, alone, heard the voice, and knew that he was alone for ever. He who, in the midst of the darkness in that giant universe his soul, could yet love the light, is about to turn from it, for he is about to undergo the Mesozoic Age, the Age of Stone:

I gin to be aweary of the Sun.

And after the piteous human longing of

Cure her of that.

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseas’d,

Plucke from the memory a rooted sorrow,

Raze out the written troubles of the braine,

And with some sweet obliuious antidote

Cleanse the stuff’d bosom of that perilous stuff

Which weighs upon the heart?

the words

She should have died hereafter;

There would have been a time for such a word

— in their very quietness, their slowness, those tears shed in the soul by those lidless eyes seem an ablation, the wasting of a rock or glacier by water-dropping, by melting.

Those two beings have passed even from the darkness of a world in which it was possible to ask

Is’t night’s predominance, or the day’s shame,

That darkness does the face of Earth entomb,

When living light should kiss it?

— a darkness of which they have become so much natives that day and night are as one:

MACBETH

What is the night?

LADY MACBETH

Almost at odds with morning, which is which,

and that yet is illumined by the vision of a lost heaven, — a heaven that lives yet in spite of their fall:

Angels are bright although the brightest fell.

From the vast universe that was Shakespeare’s mind, he produces all degrees of light and of darkness. Here then, at the end of the tragedy, we have a region like that of the Poles, where there is perpetual darkness.

In King Lear we have, first, the furious blackness of a typhoon, carrying worlds before it, then a long and prodigious Eclipse of the Sun, then peace. But over the world of Hamlet, unlike the worlds of Macbeth and of Lear, reigns a perpetual and terrible light, — the light of truth, dissolving all into its elements.’ In Syene,’ wrote Pliny, ‘south of Alexandria … a little north of the tropics … there is no shadow at noon, on the day of the solstice. … In those places in India where there are no shadows … the people there do not reckon time by hours… So, in Hamlet, that world of the terrible light in which even the dead cannot rest in the peace of the grave, there is no time: the beat of verse sometimes loses its pulse, dissolves in the light changes to the shadowless, Time-less clime of prose.

Nothing may rest in darkness.

Writing of the question of ‘the old mole’, Professor Dover Wilson (in What Happened in Hamlet: Cambridge University Press) wrote that Reginald Scott’s Discourses of Witchcraft, to which he appended ‘A Discourse upon Diuels and Spirits’, is ‘recognised by all as one of Shakespeare’s source books. Scott tells us that “the worst moiety of diuels” were divided into Acquei, Subterranei and Lucifegi, and declares that the Subterranei “assault them that are miners or pioneers, which use to worke in deepe and darke holes under the earth” (“Discourse”, chap. 3).’ Professor Dover Wilson adds: ‘we may remember too that Sir Toby Belch speaks of the Devil as “a foul collier”. After all this, is it not clear that Hamlet’s words,

Well said, old mole! canst work i’ th’ earth so fast?

A worthy pioner!

identify the mutterings of the Ghost with the rumblings of one “of those demons that are … underground”, to quote Milton?’

Probably. But may not the meaning be even deeper than that? Is not the ‘earth’ of which Hamlet speaks, his own ‘too sullied’ flesh, his body, in which many things that were hidden are now thrown up by that old mole, into the light?

Consider the raging darkness, the furious whirlwind sweep of the second scene on the Heath in King Lear, — those gigantic lines in which Lear defies the whole heaven, cries to it to blot out the world:

Blow, windes, and cracke your cheeks! rage! blow!

You Cataracts, and Hyrricanos, spout,

Till you have drench’d our Steeples, drown’d the Cockes!

You Sulphurous and Thought-executing Fires,

Uaunt-curriers to Oake-cleauing Thunder-bolts,

Sindge my white head! And thou, all-shaking Thunder,

Strike flat the thicke Rotundity o’ the world,

Cracke Natures moulds, all germaines spill at once

That make ingratefull Man.

The verse has variety as vast as the theme. The first line is an eight-syllabled one; then, under the sweep of this enormous rage, stretching from pole to pole, the lines rush forward into decasyllabics and even hendecasyllabics — (and this is not always, though it is sometimes, the result of pretended elision).

The movement is hurled backward and forward. In the first line, for instance, of those strong monosyllables ‘rage’, ‘blow’, the first sweeps onward across the world into infinity, the second is hurled backward. In

You Sulphurous and Thought-executing Fires

the vowel-sounds mount, like a rising fury, then the word ‘Fires’ (with its almost, but not quite, double-syllabled sound) gives again, though with a different movement, the effect of stretching across the firmament.

Part of the immensity of this vast primeval passage is due to the fact that in the line

Uaunt-curriers to Oake-cleauing Thunder-bolts

the only word that does not bear an accent is ‘to — and part, again, is due to the contrast between the stretching one-syllabled words of the first line and the three-syllabled ‘Cataracts’ and four-syllabled ‘Hyrricanos’ of the second. Added vastness is given by the balance between the high a of ‘rage’ and that of ‘Hyrricanos’, and by the huge fall from the a, in this latter word, to that word’s last syllable. Variety in this ever-changing, world-wide tempest is given, too, by the long menacing roll, (in the midst of those reverberating thunder-claps the c’s and ck’s of the whole passage) — the roll, gradually increasing in sound, of the first three words in

And thou, all-shaking Thunder,

rising and stretching to the long first syllable of ‘shaking’ and then falling from that enormous height to the immense, long, thickened darkness of the word ‘Thunder’.

Compare this raging blackness with the Stygian, smirching darkness of Lear’s invective on Woman, — a darkness that first has shape, but then crumbles, falls, at last, into that chaos in which the world will end. It is not for nothing that the vastly formed verse gutters down into an unshaped prose.

LEAR

I, euery inch a King:

When I doe stare, see how the Subject quakes. I pardon that mans life. What was thy cause?

Adultery?

Thou shalt not dye: dye for Adultery! No:

The Wren goes too’t, and the small gilded Fly

Do’s letcher in my sight.

Let Copulation thriue; for Gloucester’s bastard Son

Was kinder to his Father than my Daughters

Got’tweene the lawfull sheets.

Too’t Luxury, pell-mell! for I lacke Souldiers.

Behold yond simp’ring Dame,

Whose face between her forkes presages snow;

That minces Uertue, and does shake the head

To heare of pleasure’s name;

The Fitchew nor the soyled Horse goes too’t

With a more riotous appetite.

Downe from the waste they are Centaures,

Though Women all aboue:

But to the Girdle doe the Gods inherit,

Beneath is all the Fiends’.

There’s hell, there’s darknesse, there is the sulphurous pit;

Burning, scalding, stench, consumption; Fye, fye, fie! pah, pah! Giue me an ounce of Ciuet, good Apothecary, to sweeten my imagination: there’s money for thee.

GLOUCESTER

O! let me kisse that hand.

LEAR

Let me wipe it first;

It smelles of Mortality.

That world of eternal night, King Lear, contains all degrees of darkness: the advance into night of

Childe Rowland to the darke tower came,

— a night of mystery. Both the quartos print this alternative:

Childe Rowland to the darke towne came.

It is not for me to pronounce on the rightness or wrongness of this, when men who are learned have judged it better not to do so. But my instinct (and this alone can guide me) tells me that ‘towne’ may have been in that giant mind, and that certain reasons may have led to the change to ‘tower’.

If he wrote ‘towne’, then we know, beyond any doubt, what he meant. The dark towne is Death. But the reasons for the change may have been these. In the dark towne the roofs are low; our house is our coffin. We are huddled together, are one of a nation, are equal.

If we come to the dark tower, we are alone with our soul. The roof is immeasurably high, — as high as heaven. In that eternal solitude there are echoes.

Consider the change from the anguish of

You do me wrong to take me out o’ the graue:

Thou art a soule in blisse, but I am bound

Upon a wheele of fire, that mine own teares

Do scald, like molten Lead,

to the gentleness, the consoling and tender darkness of these lines, spoken by one to whom a world-wide ruin has, in the end, taught wisdom and resignation:

No, no, no, no! Come let’s away to prison;

We two alone will sing like Birds i’ the Cage:

When thou dost aske me blessing, Ile kneele downe

And aske of thee forgiueness: So wee’l liue,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded Butterflies: and heere poor Rogues

Talke of Court newes, and wee’l talke with them too,

Who looses, and who wins; who’s in, who’s out;

And take upon us the mystery of things,

As if we were God’s spies: and wee’l weare out

In a wall’d prison, packs and sects of great ones,

That ebbe and flowe by the moone.

Here, part of the gentleness, the moving sweetness, is given by the fact that in the double-syllabled and three-syllabled words, in every case excepting in two, (‘gilded Butterflies’,) every hard consonant there may be is softened by an s, ‘prison’, ‘blessing’, ‘forgiueness’, ‘mystery’.

The passages which come immediately before the death of Cordelia have all this heart-breaking sweetness. Is there another poet in the world who would have dared the use of that five-times-repeated trochee in the second line quoted below:

… Thou’lt come no more,

Neuer, neuer, neuer, neuer, neuer

— trochees that with each repetition seem dropping further into darkness? Is there another poet in the world who could have wrung from the simple repetition of one word such tears?

It is this absolute simplicity, this apparent plainness of statement beneath which lies the depth of the whole world, which makes part of his greatness: Lear touching the cheek of Cordelia, wondering: ‘Be your teares wet?’ and knowing, by those tears, that she lives yet, and is not a phantom returned to him from beyond the grave; Iago’s

… Not Poppy, nor Mandragora,

Nor all the drowsie Syrrups of the world,

Shall euer medicine thee to that sweete sleepe

Which thou owd’st yesterday;

Othello’s

… Oh now, for ever

Farewell the Tranquill minde; farewell Content,

Farewell the plumed Troope and the big warres.

This is the primal simplicity that yet holds within it the possibilities of all variations of form. His pulse is the vast rhythm that holds the worlds together, that holds the stars in their orbits.

In Antony and Cleopatra the darkness is not that of a night haunted by the Furies, and lit by the flares of Hell, but is like the beauty of one who said

That am with Phoebus’ amorous pinches black,

And wrinckled deep in time.

This night of death, into which the splendours of the day, hung with a million suns, must sink, the night in which the warrior unarms, his task done, to find sleep by the side of his lover, is a smiling darkness.

Finish, good lady, the bright day is done,

And we are for the dark.

This softness, this languor, this dark magnificence shapes the movement, lies on the last scenes like the bloom on the fruit. Even the scene with the Clown who brings death in a basket of figs, has this strange and smiling bloom, the peacefulness of death that is no more fearful than the shining darkness that lies on the figs:

CLEOPATRA

Hast thou the pretty worm of Nilus there

That kills and pains not?

CLOWN

Truly I haue him; but I would not be the party that should desire you to touch him, for his biting is immortal. … I wish you all joy of the worm.

In the slow-moving pomp and splendour of the verse in the scene of Cleopatra’s death, all the vowel-sounds, at the beginning of the passage, are dark and full, and these vowels are, in part, the cause of the movement, because they bring about the pauses:

CLEOPATRA

Giue me my Robe, put on my Crowne; I haue

Immortall longings in me: Now no more

The juyce of Egypts Grape shall moyst this lip.

Yare, yare, good Iras; quicke. Me thinkes I heare

Antony call: I see him rowse himselfe

To praise my Noble Act; I heare him mocke

The lucke of Cesar, which the gods giue men

To excuse their after wrath. Husband, I come;

Now to that name, my courage proue my Title!

I am Fire, and Ayre; my other Elements

I giue to baser life. So; have you done?

Come then, and take the last warmth of my lippes.

Farewell, kinde Charmian; Iras, long farewell.

(Kisses them. Iras falls and dies).

Haue I the Aspicke in my lips? Dost fall?

If thou and Nature can so gently part,

The stroke of death is as a Louer’s pinch,

Which hurts, and is desir’d. Dost thou lie still?

If thus thou uanishest, thou tell’st the world,

It is not worth leaue-taking.

CHARMIAN

Dissolue, thick Cloud, and Raine; that I may say,

The gods themselves doe weepe.

CLEOPATRA

This proues me base:

If she first meet the curled Antony,

Hee’l make demand of her, and spend that kisse

Which is my heauen to haue. Come, thou mortall wretch,

(To the asp, which she places at her breast.)

With thy sharpe teeth this knot intrinsicate,

Of life at once untie: Poore uenemous Foole,

Be angry, and despatch. Oh couldst thou speeke,

That I might heere thee call great Caesar Asse

Unpolicied.

CHARMIAN

Oh Easterne starre!

CLEOPATRA

Peace, peace!

Dost thou not see my Baby at my breast,

That suckes the Nurse asleepe?

CHARMIAN

O breake! O breake!

CLEOPATRA

As sweet as Balme, as soft as Ayre, as gentle, —

O Antony! Nay I will take thee too,

(Applying another asp to her arm.)

What should I stay — (Dies.)

CHARMIAN

In this uile world? So fare thee well!

Now boast thee Death, in thy possession lies

A Lasse unparallel’d. Downy Windowes, cloze;

And golden Phoebus neuer be beheld

Of eyes again so Royall! Your Crownes awry;

Ile mend it, and then play….

In the lines with which Cleopatra’s speech begins:

Giue me my Robe, put on my Crowne; I haue

Immortall longings in me; Now no more,

— the first line has the same two long dissonantal o’s as in the first line of Lady Macbeth’s

And fill me from the Crowne to the Toe, top-full

Of direst Cruelties; make thicke my blood

— but the place of the dissonances is reversed, and the effect is utterly different. This is due, in part, to the hard t’s of Lady Macbeth’s lines, and to the k and ck of ‘make thicke’. Also, in the second line of Lady Macbeth’s, the vowels are not deep, dark, and rich as are those in the second line of Cleopatra’s. In

Giue me my Robe, put on my Crowne; I haue

the long magnificence of the o’s, the first being rich and deep, but not dark, the second effulgent with brightening jewels, — these darken to the splendour of the o’s in the second line, — that in ‘immortall’ being the deepest; that in ‘longing’, in spite of the g which gives it poignancy, is soft because of the n. The o of ‘now’ echoes (though the length is less) the o of ‘Crowne’, ‘more’ echoes the or of ‘immortall’, and indeed throughout the first lines there are echoes, some lengthening, some dying away, some more air-thin than the sound of which they are a memory, because of the difference between the consonants that embody the vowels. And these echoes give the verse the miraculous soft balance of the whole.

For instance, ‘lucke’ in the 7th line is a dulled dissonance to ‘quicke’ in the 4th, and is divided from this by the darker, more hollow dissonance of ‘mocke’ in the 5th. ‘Praise’, in the 6th line, is a higher dissonantal echo of ‘rowse’ in the 5th, and ‘Come’, the first word of the 11th line, is an echo of ‘done’, the last word in the 10th. But an echo that has taken on a body. Again, in the lines

… this proues me base:

If she first meet the curled Antony,

Hee’l make demand of her, and spend that kisse

Which is my heauen to haue,

the miraculous balance is due to the dissonances ‘base’ and ‘kisse’, and the alliterative b’s of ‘heauen’ and ‘haue’. In that wonder of poetry:

CHARMIAN

Oh Easterne starre!

CLEOPATRA

Peace, peace!

Dost thou not see my Baby at my breast,

That suckes the Nurse asleepe?

CHARMIAN

O breake! O breake!

CLEOPATRA

As sweet as Balme, as soft as Ayre, as gentle,

— (the Easterne starre is Venus, the star of the east, and is also Cleopatra: is, too, the rising star of death, all three in one —) the beauty of the sound is due to the balance of the poignant e’s,— these changing to dimmed e’s, to the particular arrangement in which they are placed, and, also, to the placing and balancing of the two-syllabled words: the long e’s of ‘asleepe’ are a reversed echo of the long e of ‘Easterne’; the e of ‘gentle’ is dimmed and softened. The arrangement of the s’s gives a feeling of strange gentleness, and the fact that they are often alliterative gives balance.

The texture of the passage is for ever darkening and softening, then brightening and becoming poignant once more: ‘breast’, for instance, is a higher echo of the dusky, softened ‘dost’— ‘ayre’ is a softened, bodiless, wavering, dissonantal echo of the shorter, sharper ‘starre’.

In the first three lines of that passage which begins with the words ‘In this uile world’ there is a lovely pattern of l’s, gentle and languorous; the beauty of the dropping dissonances ‘uile’ ‘well’; ‘lies’, ‘Lasse’, ‘cloze’, is very great. And it is these, the occasional alliterations (‘world’ ‘well’ lies ‘Lasse’), the echoing o’s placed close together, of ‘Windowes’, ‘cloze’, ‘golden’, and the perpetual ground-sound (if I may so express it) of i’s and y’s,— ‘uile’, ‘lies’, ‘eyes’, ‘awry’, together with the particular arrangement of assonantal dim e’s,— ‘well’. ‘Death’, ‘possession’, ‘beheld’ mend’. which give the passage its flawless balance.

An extraordinary beauty and strangeness is given, in the last four lines of that passage, by the difference in balance and length of the double-syllabled words — the first syllable of ‘Downy’ and ‘Windowes’ being not quite equal, for the ow of ‘downy’ is longer, — the first syllables of ‘golden’ and ‘Phoebus’ being equal, and ‘Royall’ being less a word of two syllables than a word of one and three quarters.

In the midst of the youthful warmth, the eternal moonlight of the Midsommer Nights Dreame, we find these lines whose richness and dark splendour, graver than the rest of the play, might have grown, as far as its movement, its slow magnificence, are concerned, in Antony and Cleopatra; although the lovers of the Midsummer Night are younger than Antony and his Queen: it is a youthful passion that speaks, not luxury:

LYSANDER

The course of true loue neuer did runne smoothe;

But either it was different in bloud,—

HERMIA

O crosse! too high to be in thralled to loue!

LYSANDER

Or else misgraffed, in respect of yeares,

HERMIA

O spight! Too olde to be ingag’d to young.

LYSANDER

Or else, it stood upon the Choyce of friends,

O hell! to choose loue by another’s eyes.

LYSANDER

Or if there were a sympathy in choyce,

Warre, death or sicknesse did lay siege to it,

Making it momentany as a sound,

Swift as a shadowe, short as any dreame,

Briefe as the lightning in the collied night,

That, in a spleene, unfolds both heauen and earth,

And, ere a man hath power to say ‘beholde’,

The iawes of darknesse do deuoure it up;

So quicke bright things come to confusion.

The miraculous shape of this is largely due to the particular placing of the alliterative s’s — each word containing an s sound having its own particular shape, height, or depth, its own degree of sharpness — (this last effect being given by an attached h), its own peculiar length or shortness, softness or body. These variations have much effect upon the rhythm. The first syllables of ‘sympathy’ and ‘sicknesse’, for instance, although the y and the i are assonances, are not equal in length. ‘Sympathy’ has a fairly long, stretching, first syllable, and it remains on a level, whereas the first syllable of ‘sicknesse’ is, though very slightly, shorter: it is also rounded by the ck. There is a drop from ‘siege’ to ‘sound’. ‘Sound’ is longer than ‘swift’ and has a different shape, — it stretches into space and then dies away again, whilst ‘swift’, though short, has the faintest possible movement within its one syllable, owing to the f, which is, however, stopped, as soon as heard, by the t. ‘Spleene’, again, is so long a word, owing to the stretching e’s, that although, actually, it has but one syllable, it almost equals, in length, a word of two syllables.

The shape is largely the result, too, of the alliterative d’s of ‘darknesse’ and ‘deuoure’ — alliterations that gather the rhythm together. But above all, the movement of this wonderful passage is given by the changing vowel-lengths, brightening and lengthening, dimming and shrinking, and by the particular place in which the assonances and dissonances are put, — (the change from the youthful warmth of the sound of those assonances ‘bloud’ and ‘loue’, the heightening despair of ‘choose ‘‘eyes’).

Then there is the darkening of the sound from ‘spleene’ to ‘man’ (these dissonances being placed in exactly the same position in the line), the brilliant sharpness of ‘quicke bright’; then the dulling-down to the thickness of ‘come’ and the dusty shapelessness of ‘confusion’ — the drop into darkness, into chaos, of those last words ‘come to confusion’.

Let us turn from this dark magnificence to the sweet flickering shadows — (the years are but these) — cast by the summer sun over the quick-running, water-chuckling, repetitive talk of the old woman to whom,

Sitting in the sun under the doue-house wall,

the Earthquake was no more than the shaking of the dove-house as the doves prepare to fly.

NURSE

Euen or odd, of all daies in the yeare,

Come Lammas Eve at night shall she be fourteene.

Susan and she — God rest all Christian soules,

Were of an age. Well, Susan is with God;

She was too good for me. But as I said,

On Lammas Eve at night shall she be fourteene;

That shall she, marrie; I remember it well.

Tis since the Earth-quake now eleven yeares;

And she was wean’d, I neuer shall forget it,

Of all the daies in the yeare upon that day;

For I had then laide worme-wood to my dug,

Sitting in the sun under the Doue-house wall.

My Lord and you were then at Mantua.

Nay, I doo beare a braine: — But, as I said,

When it did taste the worme-wood on the nipple

Of my dug, and felt it bitter, prettie foole,

To see it teachie and fall out with the Dugge.

‘Shake,’ quoth the Doue-house:’twas no need, I trow,

To bid me trudge.

And since that time it is eleven yeares.

Here, the movement runs as fast as the small shadows over the grass. There is but little emphasis, there are but

few hard consonants. The words ‘Christian’, ‘beare’, ‘bitter’, ‘teachie’, ‘trow’ ‘trudge’, delay the movement a little, are heavier than the rest of the texture. Otherwise, all is as soft, as feathered, as the breasts of the doves in the house beneath which the old woman sits with the baby Juliet. The running movement is given by the constant use of double-syllabled words arranged in a particular manner throughout the lines, and by putting the single-syllabled words in such places that they are not emphasised, and consequently move more quickly.

Throughout the whole passage the pauses occur, it seems, only for want of breath on the part of the speaker.

I have printed this speech as verse, since it appears in the form of verse in all modern editions. But in the Quartos it is printed as prose, and I think there is much to be said for doing so, since it conveys better the pauseless movement, the quickness, the breathlessness of the old woman’s talk. The verse-beat is not very strong in this passage. In the debatable sleep-walking speeches in Macbeth it is very strong, — too strong, in my belief, if it is actually to be spoken as verse, for the situation. This leads me to think that in those speeches of Lady Macbeth, Shakespeare meant the beat to underlie rather than to rule, the sound of the speech, — to be, as it were, a reminder of that Fate-strong will overlaid by sleep, but still, though unconsciously, combating it. But with these exceptions, — still debatable ones — if any speech from Shakespeare can be heard as verse, it is probably meant to be spoken thus, no matter in what form it was printed originally. We find, over and over again, prose ‘speaking above a mortall mouth’ — as in this passage from As You Like It,— though this cannot be spoken as verse:

Leander, he would haue liued many a fair year, though Hero had turn’d nun, if it had not beene for a hot midsummer night; for, good youth, he went but forth to wash him in the Hellespont, and, being taken with the cramp, was drown’d: and the foolish chroniclers of that age found it was — Hero of Sestos. But these are all lies: men haue died from time to time, and wormes haue eaten them, but not for loue.

It is interesting to compare the speech of Juliet’s nurse, already quoted, — its comparative pauselessness, with the false fawning movement of the wicked Queen’s speeches in Cymbeline,— speeches with a serpentine intertwining motion, where the pauses do not so much stretch or divide the line, as rear themselves up suddenly, like a snake about to strike:

No, be assur’d you shall not finde me, Daughter,

After the slander of most Stepmothers

Euill-eyed unto you: you’re my Prisoner, but

Your gaoler shall deliuer you the keyes

That locke up your restraint,

and

While yet the dewe’s on ground, gather those floures,

Make haste; who has the note of them.

In the first passage, the treacherous fawning movement is produced by the trisyllabic words ‘stepmother’, ‘prisoner’, ‘deliver’.

Nor are these the only passages in these two plays which it may interest us to compare, as regards the effect of texture on the movement.

If, for instance, we examine this fragment of a speech of Mercutio:

… True, I talke of dreames

Which are the children of an idle braine,

Begot of nothing but uaine phantasie;

Which is as thin of substance as the ayre,

And more inconstant than the winde, who wooes

Euen now the frozen bosome of the north,

And, being anger’d, puffes away from thence,

Turning his face to the dewe-dropping south;

we shall see that this air-borne music, whose miraculously-managed pauses, — each like a breath of gentle air — are the result of the varying vowel-lengths, is very different from, is colder than, the lovely and wavering airiness of this speech of Iachimo’s:

The Crickets sing, and man’s ore-labour’d sense

Repaires it selfe by rest: Our Tarquin thus

Did softly presse the Rushes, ere he waken’d

The Chastitie he wounded. Cytherea,

How brauely thou becom’st thy Bed; fresh Lilly,

And whiter than the Sheetes; That I might touch,

But kisse, one kisse. Rubies unparagon’d,

How deerely they doo it.’Tis her breathing that

Perfumes the Chamber thus: the Flame o’ the Taper

Bowes toward her, and would under-peepe her lids,

To see th’ enclosed Lights, now Canopied

Under those Windowes, White and Azure — lac’d

With Blew of Heauen’s own tinct. But my designe,

To note the Chamber; I will write all downe,

Such, and such pictures. There the window, such

The Adornment of her Bed; the arras, Figures,

Why such and such: and the Contents o’ the Story.

Ah, but some naturall Notes about her Body,

Aboue ten thousand meaner moueables

Would testifie, to enrich mine Inuentorie.

O sleepe, thou ape of death, lye chill upon her,

And be her Sense but as a Monument,

Thus in a Chappell lying. Come off, come off;

As slippery as the Gordian knot was hard.

’Tis mine, and this will witnesse outwardly

As strongly as the Conscience does within,

To the madding of her Lord. On her left Brest

A mole, cinque-spotted: like the Crimson drops

I’ the bottome of a Cowslippe. Heere’s a Voucher,

Stronger than euer Law could make; this Secret

Will force him thinke I haue pick’d the lock, and ta’en

The treasure of her Honour. No more: to what end.

Why should I write this downe, thats riueted,

Screw’d to my memorie? She hath bin reading late,

The tale of Tereus; heere’s the Leefes turn’d downe

Where Philomel gave up. I haue enough,

To the trunk againe, and shut the spring of it.

Swift, swift, you Dragons of the night, that dawning

May bear the Rauen’s eye: I lodge in feare

Though this a heauenly Angell, Hell is heere.

(Clocke strikes.)

One, two, three; time, time.

The movement, which is gentle and wavering like the flame of the taper bowing toward Imogen, is the result of the particular arrangement of the one-syllabled, two-syllabled, and three-syllabled words: in several cases the line ends with a three-syllabled word, which gives a flickering sound to the line.

The texture is of an incredible subtlety. The reasons for this are manifold. Sometimes it is due to the fact that assonantal vowels, placed in close conjunction, are embodied in consonants which have varying thickness or thinness (if we can apply the word ‘embodied’ or ‘thickness’ to the unbelievably air-delicate texture of the verse). The ck of ‘Crickets’ in the first line undoubtedly gives the faintest possible body and roundness to the centre of the word, the Cr and the t the slightest sharpness, — each of an entirely different quality (for the Cr stings, while the t is sharp, but does not sting). ‘Sing’ has a slight poignancy, owing to the ng, and is therefore longer than its assonance the first syllable of ‘Crickets’. There is a tiny sharpening, again, in the second of these faint, dim assonances, ‘The Crickets sing’ — because ‘sing’ is a one-syllabled word.

Much of the beauty of the sound is due to the dissonance-assonance scheme that runs through it, and the rhythm, that lovely wavering movement to which I have referred, is, in part, the result of the arrangement of these, the way in which they are placed, sometimes close together (as with the small, dim, then sharpening sound of ‘The Crickets sing’ and the light a’s of ‘Perfumes the Chamber thus: the Flame o’ the Taper’) and sometimes echoing the original sound after a space of some lines. An exquisite effect of dimming and brightening, brightening and dimming, is produced by the use of a vowel, first faint, then brightened, or vice versa, — or by the use of alliterative consonants followed by vowels that are, first bright, then darkened.

Here is an example of the former:

… fresh Lilly,

And whiter than the Sheetes —

and of the latter:

… ere he waken’d

The Chastitie he wounded.

When, for a moment, the thought of rape enters

Iachimo’s mind, with the creeping sound of

… Our Tarquin thus

Did softly presse the Rushes,

there occurs the echo ‘fresh Lilly— ‘fresh’ being at once an altered echo of ‘presse’ and of ‘Rushes’, — as if these two words were blown together and their changed sound had become a single entity.

And whiter than the Sheetes; That I might touch.

‘Touch’ is a harder echo of ‘rushes’.

But kisse, one kisse. Rubies unparagon’d,

‘kisse’ is a distorted dissonantal echo of ‘presse’. We may notice, too, the change from the deepened, richened sound of ‘Rubies unparagon’d’ through the dimmed ‘How deerely they doo it.’Tis her’ to the brightening

… breathing that

Perfumes the Chamber thus: the Flame o’ the Taper

— this followed by the sound, flickering, bending, and straightening, blowing faintly backwards and forwards like the flame, of

Bowes toward her, and would under-peepe her lids.

This effect is produced partly by the three dissonantal o’s that accompany the w’s of ‘bowes’, ‘toward’, ‘would’, and partly by the fact that, in the two words of double syllables in this line, the first, ‘toward’, has a second syllable that is accented and fairly long, while the second word, ‘under’, has a first syllable that is, though accented, very slightly shorter than the ‘ward’ of ‘toward’.

• • • • • •

One, two, three, time, time,

And almost as Iachimo’s dark voice ceases, Time is abolished and we fall into a dreamless sleep amid the night airs. Then even the flickering taper, and its little movement that seems as if it were about to change into a sound, is gone, and we waken to find that the dark and faintly lightening, exquisite night-music has flown, and that we are listening to the sound of fluttering wings wet with dew, to the sound of the music that the clownish Cloten has brought into Imogen’s ante-chamber:

Hearke, hearke, the Larke at Heauens gate sings,

and Phoebus gins arise,

His Steeds to water at those Springs

on chalic’d Flowres that lyes; And winking Mary-buds begin

to ope their Golden eyes: With euery thing that pretty bin,

My Lady sweet arise:

Arise, arise.

Part of the beauty of that fresh, clear, and soaring movement comes from the fact of the word ‘Hearke’ being repeated twice — (the first time is a kind of springing-board for the second) — followed by its rhyme ‘Larke’ in the same line, and also because there are, for some reason, two little breaths, two little flutters, in the fourth line, between ‘chalic’d’ and ‘Flowres’, and after ‘Flowres’. The reason for the first flutter is that the word’ chalic’d’ seems drawing itself faintly together, like the calixes of those flowers when dew splashes down upon them, — (this is caused by the narrow vowels). The reason for the second flutter is that ‘Flowres’ is a word of one syllable and a fraction. The two flutters, therefore, move in a different direction; the first slightly backward, the second slightly forward.

The whole of the poem is really built upon in sounds, sometimes sharp, as with ‘sings’ or ‘winking’, sometimes faint, as with ‘gins’ or ‘bin’ — these alternating with poignant i and y sounds (‘arise’, ‘lyes’, ‘eyes’). It is this, and the particular arrangement of the double-syllabled and single-syllabled words, that give the poem its lovely, incomparably fresh, springing movement.

This is one of the few songs of Shakespeare’s that have not been subjected, at one time or another, to wrong printing.

Of the marvellous song from Measure for Measure Swinburne, in Studies of Shakespeare, wrote: ‘Shakespeare’s verse, as all the world knows, ends thus:

But my kisses bring againe,

Bring againe,

Seales of loue, but seal’d in uaine,

Seal’d in uaine.

The echo has been dropped by Fletcher, who has thus achieved the remarkable musical feat of turning a nightingale’s song into a sparrow’s. The mutilation of Philomela by the hands of Tereus are nothing to the mutilation of Shakespeare by the hands of Fletcher.’

Part of the almost unendurable poignance of the marvellous song from Measure for Measure: ‘Take, oh take those lips away’ — I speak of the technical side — is due to the repetition, to the echoes which sound throughout the verse, and part to the way in which the imploring stretching outward of the long vowels in ‘Take’ and its internal assonance ‘againe’ (and other words with long high vowels) are succeeded, in nearly every case, in the next stressed foot, by a word which seems drooping hopelessly, as with ‘lips’, and’ forsworne’, for instance.

The third line, however:

And those eyes, the breake of day,

is an exception. Here, all is hope. Indeed, the sound of ‘breake’ and ‘day’ rises after the sound of ‘eyes’.

A singular beauty, too, is given by the variation in the length and depth of the pauses. Let us examine the song for a moment:

Take, oh take those lips away,

that so sweetly were forsworne;

And those eyes, the breake of day,

lights that doe mislead the Morne!

But my kisses bring againe,

Bring againe,

Seales of loue, but seal’d in uaine,

Seal’d in uaine.

Note the lightening dissonance of ‘lips’ and ‘sweetly’, the way in which ‘breake of day’ would echo, exactly, ‘take those lips away’, but for the fact that ‘breake’ and ‘day’ are drawn more closely together by the space of one syllable. Note, too, the beauty of the assonances ‘eyes’ and ‘lights’ and how the particular position in which they are placed gives additional poignancy.

To return to the printing of the Songs. There are cases where, to my hearing, it seems that the longer line is right. The causes of speed in poetry are but insufficiently understood by many people. If the following song from A Midsommer Nights Dreame is printed thus:

Ouer hil, ouer dale,

Thorough bush, thorough briar,

Ouer parke, ouer pale,

Thorough flood, thorough fire,

it obviously moves more slowly, because of the pause at the end of each line, than if it is printed thus:

Ouer hil, ouer dale, thorough bush, thorough briar,

Ouer parke, ouer pale, thorough flood, thorough fire.

Here, the pause owing to the long vowels is less like a pause than like the stretching of wings. The fairy was evidently in a hurry, — and the flight was even, not a series of hops.

The same applies to certain of the songs of Ophelia, — I think there is much to be said for these being printed so as to give them speed. They are snatches of song, some echoes of old refrains, some outbursts of grief, whirling round and round in that distraught head:

OPHELIA

How should I your true loue know from another one?

By his Cockle hat and staffe and his Sandal shoone.

QUEEN

Alas! sweet lady, what imports this Song?

OPHELIA

Say you? Nay pray you, marke.

He is dead and gone, Lady, he is dead and gone,

At his head a grasse-green Turfe, at his heeles a stone.

O, ho!

Nay, but, Ophelia, —

OPHELIA

Pray you, marke.

White his Shrow’d as the Mountaine Snow.

(Enter King.)

QUEEN

Alas! looke heere, my Lord.

OPHELIA

Larded with sweet flowers:

Which bewept to the graue did go,

With true-loue showres.

These are, sometimes, swift as the spring rain, — sometimes sounding like the wind. But in the last song of Ophelia’s, however, the unbearably poignant

And will he not come againe,

there is a complete breakdown of the heart. The springs are broken, the slow grief has pierced through madness, dispelled even the impetus that madness gives:

And will he not come againe?

And will he not come againe?

No, no, he is dead;

Go to thy Death-bed,

He neuer will come againe.

His Beard was as white as Snow,

All Flaxen was his Pole:

He is gone, he is gone,

And we cast away mone:

God ha’ mercy on his Soule.

Incidentally, a light is thrown on the sentence

Well, God’ild you. They say the Owle was a Bakers Daughter. Lord, wee know what we are, but know not what we may be. God be at your Table!

by the fact that a person was arrested in the time of Mary I for the libel of writing that King Philip preferred ‘Bakers’ daughters’ to Queen Mary. From this we may gather that ‘Bakers’ daughters’ was a synonym, in that age, for women of loose character.

If this be so, the phrase has more than one meaning: The daughter of joy, the light liver, becomes the harbinger of death and of woe. This is one meaning.

But I have wandered far from the Fairy’s Song of the Midsommer Nights Dreame, and must return to it.

Ouer hil, ouer dale, thorough bush, thorough briar,

Ouer parke, ouer pale, thorough flood, thorough fire,

I do wander euery where, swifter than the Moone’s sphere;

And I serue the Fairie Queene,

To dew the orbs upon the green;

The Cowslippes tall her pensioners bee,

In their gold coats spots you see:

Those be Rubies, Fairie fauors,

In those freckles liue their sauors.

I must go seeke some dew drops heere,

And hange a pearle in euery cowslippe’s eare.

In the line

The Cowslippes tall her pensioners bee,

the three-syllabled word ‘pensioners’ has a little trembling sound, like that of dew being shaken from a flower.

Note, too, the effect on the rhythm of the rising, brightening dissonances and the darkening dissonances and, too, of the alliteration in the first two lines, — also the still sharper and brighter, flying effect, brought about by the internal rhymes ‘dale’ and ‘pale’, put at exactly the same place within the lines:

Ouer hil, ouer dale, thorough bush, thorough briar,

Ouer parke, ouer pale, thorough flood, thorough fire;

‘hil’ brightens into ‘dale’,’ bush’ deepens into ‘briar’, then darkens into ‘parke’, this rises again and brightens into ‘pale’, so that we see the fairy flying through the sunlight and shadow of that immortal spring. Again in the line

In their gold coats spots you see,

after the bright assonances of ‘gold coats’, we have a slightly darker dissonance to ‘coats’ in ‘spots’.

A fresh and lovely balance is given to the lines

These be Rubies, Fairie fauors,

In those freckles liue their sauors,

by the fact that though ‘Rubies’ and ‘freckles’ appear to be equivalent in length, actually they are not so. ‘Rubies’ is longer, because of the vowel-sound.

Elsewhere in the Midsommer Nights Dreame, what miracles are performed by the use of sharpening r’s, as in the first two lines of

… hoary-headed frosts

Fall in the fresh lap of the crimson Rose,

And on old Hyem’s thinne and Icie crowne

An odorous Chaplet of sweet Sommer buds

Is, as in mockery, set.

Though here the beauty of the sound is due as much to the deep breath of the alliterative h’s (hoary-headed) and the dimming. f’s which succeed these; and, too, to the wonderful design of o’s.

But the texture of the whole scene is one endless miracle.

An enchanted beauty is given by the lingering l’s in ‘Lady’ and ‘Land’ of Tytania’s

Then I must be thy Lady; but I know

When thou hast stolne away from Fairy Land

— a sound echoed again in ‘loue’ and ‘Phillida’ in the succeeding lines:

And in the shape of Corin sate all day,

Playing on pipes of Corne, and uersing loue

To amorous Phillida.

There is a strange darkening and concentration, changing of shape, from ‘Corin’ to the sound of ‘Corne’.

As I have pointed out elsewhere, elisions in blank verse are often but pretended elisions, and are an excuse for variety, since the supposedly elided syllables exist and are not muted. Sometimes, as in King Lear, these pretended elisions produce the effect of the shaking of a huge and smoky volcano — (we find this effect, too, though it is less vast, over and over again in Paradise Lost)— or they swell the line, moving it slightly forward, rearing it upward, like the beginning of a tidal wave, and presaging the final break and the shattering roar of that wave. Sometimes, again, as in Perdita’s speech, pretended elisions give a line the faintest possible increased length, or produce a faint dip in the line (the word ‘Flowres’, for instance, has this last-mentioned effect):

… O Proserpina!

For the Flowres now that frighted thou let’st fall

From Dysses Waggon! Daffadils,

That come before the Swallow dares, and take

The windes of March with beauty; Uiolets dim,

But sweeter than the lids of Juno’s eyes,

Or Cytherea’s breath; pale Prime-Roses,

That dye unmarried, ere they can behold

Bright Phoebus in his strength, a Maladie

Most incident to Maids; bold Oxlips, and

The Crowne Imperiall, Lillies of all kinds,

The Fleure-de-Luce being one. O, these I lacke

To make you Garlands of, and my sweet friend,

To strewe him o’re, and o’re.

If we examine this, we shall find that the beauty of the sound owes much to the fluctuations caused by the pretendedly elided syllables in ‘Flowres’ and ‘Uiolets’, and to Shakespeare’s genius in the use of the falling foot, — (Proserpina, Cytherea, — names which fall with a flowerlike softness and sweetness). Then, again, much beauty is given by the fact that the last syllable of ‘Daffadils’ echoes the vowel-sound of ‘Dysses’, and that ‘lids’ is an echo (but the faintest possible fraction higher) of ‘dim’. Note the change in the texture when we come to:

… pale Prime-Roses,

That dye unmarried, ere they can behold

Bright Phoebus in his strength.

Here all is brighter, owing to the high echoing i sounds following the dim i of ‘lids’. Nor is this the result of association alone, for in the rest of the fragment the texture varies, growing richer with the sound of ‘bold’ and ‘Crowne’ in the phrase

… bold Oxlips, and

The Crowne Imperiall.

One of the most wonderful of all examples of Shakespeare’s genius in the use of the Falling Foot is in Desdemona’s line:

Sing all a greene Willough must be my Garland.

I was once privileged to hear this miraculous line changed to

Sing all a greene Willough my Garland must be!!

This is, in all probability, the greatest sonnet in the English language, with its tremendous first lines:

Deuouring Time, blunt thou the Lyons pawes,

And make the earth deuoure her owne sweet brood;

Plucke the keene teeth from the fierce Tygers yawes,

And burne the long liu’d Phoenix in her blood;

Make glad and sorry seasons as thou fleets,

And do what ere thou wilt, swift-footed Time,

To the wide world and all her fading sweets;

But I forbid thee one most hainous crime,

O, carue not with thy howers my loues faire brow,

Nor draw noe lines there with thine antique pen,

Him in thy course untainted doe allow

For beauties pattern to succeeding men.

Yet doe thy worst, ould Time; dispight thy wrong,

My loue shall in my uerse euer liue young.

The huge, fiery, and majestic double vowels contained in ‘deuouring’ and ‘Lyons’ (those in ‘Lyons’ rear themselves up and then bring down their splendid and terrible weight) — these make the line stretch onward and outward until it is overwhelmed, as it were, by the dust of death, by darkness, with the muffling sounds, first of ‘blunt’, than of the far thicker, more muffling sound of ‘pawes’.

This gigantic system of stretching double vowels, long single vowels muffled by the earth, continues through the first three lines:

And make the earth deuoure her owne sweet brood;

Plucke the keene teeth from the fierce Tygers yawes,

And burne the long-liu’d Phoenix in her blood.

The thick p of ‘pawes’ muffles us with the dust, the dark hollow sound of ‘yawes’ covers us with the eternal night.

The music is made more vast still by the fact that, in the third line, two long stretching double vowels are placed close together (‘keene teeth’), and that in the fourth there are two alliterative b’s,— ‘burne’ and ‘blood’, these giving an added majesty, a gigantic balance.