At four o’clock Alvarez comes to tell me everything is ready. I immediately arise and go to the door of the shed. The air is clear and tepid, the sun hangs motionless in the east. The wind is still blowing gently from the south. It is not as much wind as I had hoped, but perhaps it is enough. Turning my back to it, I pause for a reflective moment to look northward in the direction of our hopes. Before me a beach of brown gravel stretches away a few hundred metres to the sea, a flat and endless grey surface wrinkled only slightly by the wind. At the edge of the water, bound to earth with a complicated system of ropes, is the Prinzess on which all our schemes and efforts have concentrated for so many months. Beyond her, only a mile or so across the strait, the shape of Amsterdam Island is clearly outlined in this crystalline morning light, and along to the right is the larger mass of Vasa Peninsula. The temperature, I note, is five degrees centigrade.

Alvarez is standing at my elbow, and without turning to look at him I know he is watching me with an expression I have come to recognize not only in him but in the other members of the supporting party, from the doctor to the last cook and carpenter in these final days as our preparations have drawn to a climax. They look at us as though we were dead, or more precisely, in the way one might look at men who are to perish in some bizarre and complicated way previously unknown to human experience, men who are to be executed perhaps by some new and intricate apparatus whose effects are unknown and might involve some unexpected and unimaginable ecstasy before the final annihilation. It is not exactly a sympathy. The experience that lies before us is so unprecedented that they, the men who observe us, have no sense of participation in our fate, knowing it is one reserved exclusively for us and not, like death from an ordinary illness, something that they themselves may be eventually destined to experience. And so their glance is one of curiosity rather than sympathy or envy, and is quite distant and detached in its regard; it is a speculation as to what we might be experiencing in our thoughts and sensations in this thing that is already beginning to happen to us and will soon separate us inexorably from all the other men of the earth. It is the look one might give to men who were about to voyage to the moon, or be mated to goddesses or wraiths. Perhaps we are, although I am not quite sure which I mean, or what I mean by that. I would do better to avoid fanciful metaphors and concentrate on the task at hand.

Alvarez, the crew chief, is an Argentine and knows neither English nor Swedish. Since I know no Spanish we communicate in the French which is the working language of the base camp. In any case Alvarez is not loquacious; he works with his hands and his brain and speaks only when necessary for the job at hand. After a while, still watching me out of his tanned face without expression, he merely inquires, “Ça va?”

He means the wind. I tell him it is adequate, perhaps. “And there are disturbances to the southeast. In a little while there may be more wind than we can use or need.”

“Then we should start preparing the Prinzess?”

“Of course. Immediately. Remove what is necessary. Leave only the three ground ropes if you like.”

“D’accord, Commandant.”

With barely a nod to me, his face still expressionless, he disappears in the direction of the workshed. After only a moment I can hear his sharp voice through the walls of the shed. “Allons les gars—a l’éveillée! Tout est rassemblé—où sont les couteaux? On part!”

Most of the preparations have been completed for several days and what remains to be done is a matter of twenty minutes or so: removal of the lashing ropes, checking of instruments, loading of the final equipment. Out of habit, although I know almost precisely what it will say, I glance at my watch: a little less than ten minutes after four. Then, after a last appraisal of the wind, I go back into the sleeping shed to wake the others. Waldemer is already up, busying himself seriously and a little sleepily with the personal possessions he plans to take with him. When I touch Theodor’s shoulder he says nothing, only looks at me with eyes that from the moment they open fix me steadily without so much as a glance at the other objects in the shed. Then he comprehends and pulls himself out of his sleeping sack without a word. The sleeping sacks are of reindeer leather with the fur inside, warm, but I can predict that the hairs they shed will be an annoyance. Theodor efficiently rolls up his sack; he seems as wide awake as if he had never been asleep, although he is still not very talkative. So much the better! We have not come to this place to talk. We should emulate Alvarez.

I quickly dress and collect the few instruments I have not embarked the night before: field glasses, the level sextant, the two pocket chronometers. (I speak of night only from habit since at the latitude of Spitsbergen the summer sun is always skulking around the horizon like a kind of friendly and stupid animal.) With Waldemer I walk down to the edge of the water and verify for myself that the instruments are carefully installed in the gondola. Waldemer stows his photographic apparatus, which except for the folding tripod fits neatly into a kind of leather portmanteau with a handle at the top. We have time for a final check of the chronometers Kullberg 5566 and Kullberg 5587. Still two minutes and thirteen seconds apart; the rates are constant. Then we go back to the sleeping shed where Theodor is lacing up his boots, his mouth set in a little crease of seriousness on one side. The doctor, alerted by Alvarez, has come ashore from the Nordkapp anchored in the bay and is waiting to examine us one last time. Except for Theodor and me he is the only one who knows—as inevitably he must know—the oddness that rests at the centre of this trio of us. A bear of a man with unkempt grey hair and whiskers, he applies a stethoscope to our chests in a rather perfunctory way. We have no fevers, palpitations, or visible fungi that would prevent us from carrying out our folly, as he regards it.

“Do you have dreams, Major?” he asks me unexpectedly.

“Dreams? What kind?”

“Of flying, for instance. Or climbing mountain peaks. Odd dreams, as they seem to you.”

I might have told him that even my waking existence seems rather odd to me, but we have no time for a pleasant conversation on epistemology. “Do you ask in the interests of science, or merely to verify my health?”

“I’m perfectly healthy. I’d be glad to engage you in Indian wrestling if you like, but some other time. Are you done with us?”

“I am speaking to you now not as a physician but as a man. It would be too much to say that I am fond of you. I am not. But I am concerned over what you are doing to yourself, and to others, as I would be for any human being.”

I simply meet his glance and look back at him, politely but without any expression. After a moment he takes me by the elbow and we move toward the door of the shed; outside he draws me a little apart from the others.

“Flesh has its limits, and different flesh has different limits. What you are concealing in this matter is more than an indiscretion, it is a crime. Besides I think you will find that this mischief you have made will defeat your own purposes.”

“Are you sure you know my purposes?”

“I would have thought they were fairly clear.”

I smile and might have remarked that he knows more than I do, then. But I only say, “If I am a criminal you ought to have told the authorities.”

“I have sworn to you to say nothing, and you know that I will not. But you are taking a life in your hands—three lives, although I hold you more greatly responsible for one of the three.”

“I am grateful for your advice. Goodbye, Doctor.”

To my surprise he doesn’t reject my hand and responds almost warmly, it seems to me, to the pressure of my fingers. But there is no smile of sympathy on his face, only an immobility—not of disapproval, one has the impression, but of indifference—that contrasts oddly with the cordiality of his grasp. He turns and without a word goes back toward the ship, not waiting to witness the crucial moment of this enterprise for which we have prepared for so many weeks.

For the second time this morning I make my way down the shingled beach to the water. The great roundness at the water’s edge, stretched upward as though by the force of some mysterious and insubstantial gravity, curves at the bottom into a kind of dimple or extrusion resembling the mouth of a chemical flask. The net of light cord stretched over it is another geometry of reticulation imposed on this sphere. I am struck for the first time with the beauty of the form: the Prinzess strains upward, the ropes downward, and in their blind logic these forces have created an ellipsoid of exquisite feminine roundness. The alternate segments of red and white silk, tapering to points at the top and bottom, are each of them perfect shapes according to the laws of spherical geometry, yet when glanced at again they disappear as separate entities through a kind of optical trick and merge into this rounded whole to which nothing could be added and nothing taken away. The whole gives the impression of something ethereal in its substance and yet perfect in its concept, like the thought of a mathematician. As the breeze touches it, the shape trembles, dimples here and there, and then resumes its geometric curve. The red and white stripes, which are functional and intended to increase the visibility of the Prinzess at long distances, seem an intrusion, almost a frivolity in the barrenness of the surrounding landscape. Everything else is grey or brown, the sea is the colour of iron. The wind is holding constant at eight knots from the south.

At the water’s edge a considerable crowd has collected: workmen, cooks, sailors from the Nordkapp, old Captain Nyblom, whom I have known from the time of the Greenland expedition. Alvarez is on top of the gondola checking the guide ropes and verifying the screw mechanism that detaches them in case of entanglement in the ice or for some other reason. My two companions stand by the gondola with their hands on the instrument ring, waiting for the word to mount. Theodor is elegant as usual in a fur-lined German officer’s greatcoat, a peaked cap, and boots which came from Foirot in rue Saint-Honoré. I glance at his face for a sign of emotion, but he seems completely self-assured, with the faint touch of arrogance or contempt that is part of his nature. He has trimmed his hair short and neatly cleaned his fingernails, I see, in preparation for the flight. Waldemer is wearing a thick padded shooting jacket and a hunting cap with flaps, and you sense rather than perceive that there is long woolen underwear beneath, the American kind with a door at the rear, a most practical arrangement. As for me, I am clad in the outfit made for me by the Greenland Eskimos in 1882; a coat of reindeer skin with a hood, breeches of the same material, and sealskin boots.

Alvarez comes down from his inspection of the guide ropes; he has checked the manoeuvring valve carefully and verified the ballast. We haven’t bothered with breakfast; there is no time to lose if we are to take advantage of the favourable wind. The lines that hold the Prinzess to earth have been removed except for three stout ropes of Manila fixed to stakes. Three workmen are standing by these with knives we have been careful to sharpen the night before. There is a certain amount of conventional handshaking, which makes everyone concerned feel rather silly. Alvarez is the enemy of all sentiment and does not participate in this ceremony. Not looking directly at me, his eyes fixed on the lower part of the gondola, he merely says crisply, “Bonne chance, Commandant.” Captain Nyblom, for some reason, shakes his head slowly, without altering his wrinkled Norwegian smile.

Somewhat impeded by our heavy clothing, we climb up into the gondola. Because of the bulky shooting jacket Waldemer has some difficulty crossing the instrument ring, and is immobilized for some time with one leg on one side of it and one on the other. No one shows even the faint trace of a smile at this (and again I think of condemned men who are being adjusted into some execution machine which malfunctions slightly so that there is a delay in the proceedings; it is with exactly that combination of detached silence and curiosity that the spectators watch us), and by unbuttoning his coat at the bottom I manage to help him across and in. “Thanks, Major.” He is puffing a little at this incident. But he is smiling; if he can climb so smartly over the instrument ring then surely he, and all of us, can do the rest! Theodor shows no sign that he has observed this little playlet. He has swung over the ring as though it were an exercise he has performed a thousand times, and now he stands quietly waiting for the next order, with his gloves resting on the wicker of the gondola. I notice that his earlobes are already grey, and I wonder if he will be able to endure the much greater cold we are soon to encounter.

Now that we are aboard, the mechanic Eliassen and his helper attach a spring scale to the bottom of the gondola and pull it down a little to measure our buoyancy: eleven and a half kilos. Alvarez is waiting for a lull in the wind. The ropes creak, at my feet the pigeons supplied by a Stockholm newspaper coo softly in their wicker case. There is a faint and not unpleasant smell of kerosene to the south in the centre of the island, some round grey knobs of hills are watching us like a circle of spectators. Slightly to the east of north lies the larger mass of Spitsbergen, mountains we can’t hope to climb over and must skirt with the help of this wind which we hope won’t turn fickle. In the other direction, a quarter of a mile away, the Nordkapp with her tall narrow funnel and her squared foreyard rests docilely at anchor in the bay. It is too far away to see if the doctor is watching, but I’m sure he isn’t; he is no doubt in his cabin writing up the notes of the examination. The time, a minute or two after five. I can no longer see Alvarez because he is directly under the gondola, but I can hear his voice speaking French with its brisk consonants, asking for the last time if everything is ready, warning all hands to stand clear of the guide ropes. At the last moment Eliassen comes running across the gravel with something in his hand and I catch the word dagboken: I have forgotten the pocket diary bought only two weeks before on Drottninggatan in Stockholm in which I am to record my notes of the voyage. The diary is handed up amid jokes about absentmindedness. From under the gondola the telegraph-like voice continues to give orders.

“Attendez un moment … calme … attendez.”

There is a pause, so silent that we can hear the ticking of the two chronometers and the sound of the air in the rigging, and then the note of the wind drops a little.

“Coupez! Coupez tout!”

At the same instant I feel the gondola stir, lurch to one side, and rise slowly. The white faces below are a clump of strange flowers, damply pale against the brown of the beach, following our motions as sunflowers follow the sun. Everything below us, the sheds, the camp, the white faces looking upward, dwindles and shrinks as if pulled to a centre by invisible lines of force. I look over the side to be sure the guide ropes are trailing property. They slither over the beach and enter the sea, where they follow behind us leaving three snaky furrows on the water. Slowed by their drag, the Prinzess begins to tilt sideways. We begin to descend toward the sea, slowly at first, then dropping lower at an alarming rate. As the wave tops come up I see quite clearly, not more than two metres below us, something gleaming on the water: a piece of tinfoil or silver paper, probably a wrapping of a photographic plate from the pictures we took yesterday. Waldemer has his hand on the ballast string. But we must not release ballast too soon; if we do we will also have to release gas in order not to soar too high, and we will need the gas later. At the last moment he pulls the drawstring and a stream of fine lead shot slithers downward with a hiss. Almost at the same instant the gondola strikes the water with a heavy, almost metallic sound. We are thrown sideway against each other and keep our balance only with difficulty. Waldemer gropes for the ballast string again but I reach for his arm and restrain it. The gondola touches the sea once more, not quite so heavily this time, and this last contact with the terrestrial sphere seems to lend it force. The Prinzess lifts a little, hesitates and descends, and then begins to climb again. The guide ropes lift evenly up until only about a third of their length is still trailing in the water.

Waldemer catches my eye and shakes his head, smiling now, but still panting a little from the excitement.

“The vixen! She almost gave us a bath before we were decently off!”

Theodor says nothing. The camp behind us and the semicircle of watchers are almost invisible now. On the beach we can make out the sheds and, barely detectable in front of them, some pinpoints and variegated spots, our last glimpse of human beings. The ship in the harbour is a toy. To the northeast I see land I have previously known only from the chart: the end of the Vasa Peninsula, Vogelsang and the other outlying islands. Waldemer suddenly remembers something. He opens the leather portmanteau and unlimbers his photographic apparatus: a large oaken box with a goggle on the front of it, the tripod, and a number of plates with their holders. He unwraps the tinfoil from a plate and throws it overboard, and it sinks downward with an odd slowness like a silver bird. The plate snaps in and out of the slot. Like all specialists he grumbles at his tools. “At that range of course … And from a moving platform.” What will show on the plate are some flyspecks. But his journalist’s instinct is satisfied and our departure is recorded for posterity, insofar as posterity reads the Aftonbladet and the New York Herald. Theodor has mounted the theodolite and is taking a final bearing of the camp to verify our course. He inclines the tube downward, adjusts it to align exactly on the camp, reads the bearing of the azimuth ring, and makes an entry in his notebook. It seems incredible that we are off at last. I open my own pocket diary, find the page “12 juli,” and write, “0501 GMT. Ascent from Dane Island. Wind S. 8kt., sky clear.”

![]()

My emotions are complicated and not readily verifiable. I feel a vast yearning that is simultaneously a pleasure and a pain, like a desire for a woman. I am certain of the consummation of this yearning, but I don’t know yet what form it will take, since I do not understand quite what it is that the yearning desires. For the first time there is borne in upon me the full truth of what I myself said to the doctor only an hour ago: that my motives in this undertaking are not entirely clear. For years, for a lifetime, the machinery of my destiny has worked in secret to prepare for this moment, its clockwork has moved exactly toward this time and place and no other. Rising slowly from the earth that bore me and gave me sustenance, I am carried helplessly toward an uninhabited and hostile, or at best indifferent, part of the earth, littered with the bones of explorers and the wrecks of ships, frozen supply caches, messages scrawled with chilled fingers and hidden in cairns that no eye will ever see. Nobody has succeeded in this thing and many have died. Yet in freely willing this enterprise, in choosing this moment and no other when the south wind will carry me exactly northward at a velocity of eight knots, I have converted the machinery of my fate into the servant of my will. All this I understand, as I understand each detail of the technique by which this is carried out. What I don’t understand is why I am so intent on going to this particular place. Who wants the North Pole! What good is it! Can you eat it? Will it carry you from Gothenburg to Malmö like a railway? The Danish ministers have declared from their pulpits that participation in polar expeditions is beneficial to the soul’s eternal well-being, or so I read in a newspaper. It isn’t clear how this doctrine is to be interpreted, except that the Pole is something difficult or impossible to attain which must nevertheless be sought for, because man is condemned to seek out and know everything whether or not the knowing gives him pleasure. In short, it is that same unthinking lust for knowledge that drove our First Parents out of the garden.

And suppose you were to find it in spite of all, this wonderful place that everybody is so anxious to stand on! What would you find? Exactly nothing. A point precisely identical to all the others in a completely featureless wasteland stretching around it for hundreds of miles. It is an abstraction, a mathematical fiction. No one but a Swedish madman could take the slightest interest in it. Here I am. The wind is still from the south, bearing us steadily northward at the speed of a trotting dog. Behind us, perhaps forever, lie the Cities of Men with their teacups and their brass bedsteads. I am going forth of my own volition to join the ghosts of Bering and poor Franklin, of frozen De Long and his men. What I am on the brink of knowing, I now see, is not an ephemeral mathematical spot but myself. The doctor was right, even though I dislike him. Fundamentally I am a dangerous madman, and what I do is both a challenge to my egotism and a surrender to it. To the doctor then I am a criminal, to the Danish ministers some kind of prophet or saint. Or I will be if I succeed. Succeed in what? I had forgotten my own arguments on the pointlessness of my goal.

I don’t note any of this in the diary, of course, nor do I confide it to my companions. I have already come to realise that this little book only a few centimeters square, with its prim calendar in Swedish and its toylike printed phases of the moon, will be totally inadequate for transcribing the true record of what is to come. For what is to happen can only happen inside our three minds, and will be recorded there in the infinitely complicated system of fibers and electrical charges that we call the memory, without understanding very clearly what we are talking about. The outward events become instantly nonexistent except insofar as they are fixed by this mysterious organ. The important events that happen to me in the next few days will therefore be those that take place inside my own mind. I hardly propose to communicate these complicated cerebral events to my companions and even less to the world at large, even if it were possible to do so, which it is not. The contents of the mind are infinite in their convolutions and at any given instant couldn’t be encompassed by a hundred encyclopedias, let alone by a small pigskin booklet costing two kronor. So it is clear that like Columbus I must keep two diaries, the pigskin booklet devoted to what are crassly called facts, and the other a Mental Diary in which the true events of the next few days are recorded. The log that Columbus showed to his crew was a lie; all the positions in it were false and designed to allay their fears that they were about to fall off the edge of the world. And the pigskin book too is destined to lie, although not quite in the same way. It is destined to lie because the outward events of our lives bear little or no relation to what is really happening to us. The pleasures and pains that come to the body from the outside are pinpricks; the intelligent mail regards them with contempt. It is not the body but the mind—this monster, this tyrant—that must be tricked and deluded into thinking that its lot is a happy one. The outer world exists only in my perception of it, and this perception is bent always by the shimmering lens of my consciousness. So it is clear that the Mental Diary must concern itself both with inward and outward events. And it is clear too that in this odd document the past and present must mingle, like layers of warmer and colder water merging gradually in a sea. Each sensation, in the instant it is perceived, becomes a recollection. And between near and far recollections there is little to choose. Luisa in the drawing room in Quai d’Orléans, Theodor only a metre away from me in the gondola—one is real and the other only a kind of ephemeral Magic Lantern projected on those brain fibers crawling with electricity. But which? I have only to close my eyes and they blur and merge, the profile at certain angles of the head is the same, his contempt is her pale chastity, his courage her quickness to anger. Do I know for a certainty—I ask myself—that this feel of the instrument ring under my gloved hand is a fact, and that the smell of a sun-warmed cab horse, the clop of hoofs on an avenue in the Bois, are memories? For the feel of the instrument ring too becomes a memory, in the very instant that I seek to grasp and comprehend it.

![]()

Probably not everybody shares these little difficulties. It is my strength and my weakness—I have finally come to realise—that I have a strong sense of the presence of the invisible, that forces unseen by others are quite real and present to me. Certainly Waldemer has no difficulty dealing with the external world. He himself is a part of it, solidly three-dimensional against the whitish background of the horizon. There is no question whether he is in Paris or here in the gondola. Just now he is developing the plate from the photograph he took at the time of our departure. Although he is only a recent initiate to the mysteries of photography, he is already adept at it and speaks knowledgeably of its chemistry, preferring for development the recently discovered alkaline process using pyrogallic acid, which permits exposures of a fifth of a second or less. Just now he, or at least his head and shoulders, are underneath a little tent of black cloth which he has erected over the opened portmanteau and its contents. Inside, he is carefully sloshing the plate in a tray of pyrogallol with potassium bromide, then fixing it in a solution of hyposulphite of soda, then meticulously washing it for several minutes in fresh water. Now he emerges into the daylight with the plate gripped carefully by the corners, holding it between himself and the sun in order to look through it: but the pose, a hieratic one, suggests that he is holding it up to this solar deity for inspection or perhaps for commendation.

“Ha! Well, the range was a little extreme, as I thought. Still—”

He hangs it up in the rigging by a pair of clips provided for the purpose. He is not quite satisfied with it, yet he is satisfied with it. Just doing something requiring this quantity of apparatus, and this degree of specialized knowledge, is a satisfaction to Waldemer. Like many or most Americans—undoubtedly the reason for the success of that remarkable nation—he feels obliged to be doing something at all times. A sigh or two of satisfaction, a glance around the horizon, and he is squinting into the theodolite which Theodor has left mounted on the instrument ring. He puts the canvas cover back on the instrument.

“I make out our course to be north by east a half east.”

“Very good.”

“Hard to tell now though, because the guide ropes are out of the water and you can’t sight along them. The sun has come up out of the mist and is warming the gas, and that’s made us rise. We could use that handful of ballast we threw away now.

This is self-evident.

“Hallo, it’s eight o’clock. About time for a little breakfast, I think. I’d be glad to fix it.”

He is right on all counts. The sun has climbed out of the hazy ring around the horizon and is glowing more warmly now, with a kind of swimming on the surface if you look at it directly. Penetrated by this energy, the Prinzess swells and rises. The three guide ropes, which were previously streaming behind us in the sea, now hang directly down with their ends clear of the water. We can no longer estimate our course by the snaky trails they leave in the water, and from now on we must depend on the sun compass. Waldemer is correct as well about the time, which he has derived from his reliable pocket watch, manufactured in Massachusetts. It is true that it is about time for breakfast, and even more true that he would be glad to fix it. He is always happy to do anything of immediate and practical benefit to himself and others, especially if it involves the use of any sort of mechanical apparatus. Breakfast not only involves the primus stove—a simple but admirable machine in its own right—but the contrivance which Waldemer has invented to prevent the stove from igniting the hydrogen in the immense silken bag over our heads. First the coffee pot is filled with water and charged with the proper amount of coffee. Then it is set on the stove and held in place by a clamp, and the whole affair is lowered below the gondola on a rope some ten metres long. Waldemer carefully jerks away at two strings, one attached below to a patent English stove lighter and the other to the lever controlling the fuel. Finally, after a number of failures there is a yellow flicker underneath, along with the odour of burning kerosene. The flame turns blue; the stove is operating properly.

“Ahah,” sighs Waldemer. He is pleased with himself. I smile too and am happy for him that the stove lighter has worked properly. He is really a splendid fellow, a hero of our time. Even though he is a journalist by profession, his true mission in life is to preside over his stove lighters, firearms, and all the other clever mechanical devices that an overbred civilization has come to regard as necessities. He is an emblem of our century, and even more of the century to come, the era of self-propelled carriages that will eventually do away with legs. He prefers tinned roast beef to a cow, not because it tastes better, but because the manner of its containment in the tin is ingenious. He is free from sentiment about nature. An animal to him is something to be looked at through a gun sight, something that falls down and turns into meat when the exquisite mechanism of the trigger is actuated. He has no hostility to animals, he simply regards them as somewhat inferior machines, smelly, you know, and prone to brucellosis and other mechanical maladjustments. Waldemer is an old companion of my adventures. He is necessary to me because without him I am only something more than half a man; I am incapable of taking an interest in a stove lighter. Together we are at least a man and a third. Machines are not perfect of course and neither is Waldemer. Occasionally things do not work out as he plans. This is fortunate, because if he were as infallible as machines are in the dreams of their designers he would not be human and I would not care for him as I do. Machines turn; their wheels turn, and with each turn of the wheel a minute atom of substance is worn away and the machine is no longer the same. Besides, there are—imponderables. This Waldemer has never understood. Sometimes a machine of this sort, believed to be perfect but actually possessing a soul, will turn on its maker with a quiet treachery far more dangerous than that of any animal. But—

In a reverie I imagine that it was my ancestor who invented fire and Waldemer’s who invented the wheel.

![]()

The first glimpse I ever had of him was emblematic of the whole man: he overtook me one summer day on a country road in Pennsylvania, borne along on a bicycle, that ingenious device that man has contrived as an extension of his locomotor apparatus. A bicycle is interesting to a mathematician. It deals with the well-known difficulty with legs, that there are only two of them. One being constantly brought forward into position for the next step, the weight of the body is left on the remaining one, a precarious condition which results in lurching and inefficient motion. For this reason nature has evolved the horse and other four-legged animals, so that a sufficient number of legs will always be where they are needed without an undue effort. But the wheel is vastly superior to the quadruped. By a well-known mathematical principle, the number of legs is increased until it approaches infinity; analogically speaking, the polygon is extended to the circle. Now there is always a leg—that is to say a mathematically infinite point of the wheel—under the progressing body. The rider can relax his own legs at will, for short periods, and it is not even necessary for him to mind very carefully what he is doing. The wheel in its dumb perseverance will take care of the physics for him. His progress is assured, and he can add momentum or subtract it as he pleases by working the pedals or the brake in turn. Regarded purely as a locomoting animal, he has converted himself into a greatly improved one by combining himself with the product of his thought. Thus Waldemer, appearing behind me on the outskirts of Harrisburg on that bucolic summer day, waved cheerily, braked on the dusty road, and fell flat in front of me along with his machine.

Only a little less cheerful, he extricated himself from the bicycle, slapped the dust from his clothing, and introduced himself. He was about thirty in those days, a stocky young man with a handsome head, horizontal eyebrows, and a soft but bushy mustache shaped like the handlebars of his bicycle. He resembled exactly one of those clean-cut heroes in the American dime novels I had read as a boy in Stockholm, those who smile but only with a little wrinkle-of-takinglife-seriously between their brows, and this was prescient, because it was exactly one of those boys’ adventures that he and I were setting out on together. He was irrepressibly good-natured and there was no question whatsoever about his intelligence. He had just begun work as the central Pennsylvania correspondent of the New York Herald, and he regarded his encounter with me as his first opportunity (he was fond of the word opportunity, quintessentially American as he was) to move from his small-town origins into the realm of world events. After he had explained the circumstances, he helped me onto the handlebars of his machine, and together we went on down the road in search of Woodlawn State College and Professor Eggert.

Cuthman Eggert was at that time a leading authority on aerostatics. I had come to him ostensibly out of curiosity, but at a deeper level no doubt because some demon inside me sensed that balloons were to play a part in my destiny. I had known he was interested in the problem of dirigibility because of his papers, which I had read in the library of the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, and he in turn had taken note of my own publications on aeromagnetics. We corresponded, exchanged opinions, and agreed to meet—I because what I was interested in lay up in the sky too high to be reached with ladders, and he because he hoped, perhaps, that my knowledge of magnetic phenomena might be of some use to him in solving the problem of the dirigibility of aerostats. He proved to be a humourless man with a bony frame, a little smaller than ordinary size, intensely devoted to his researches and scarcely aware of the practicalities of daily life around him. He had no small talk. He proposed an ascension for that very afternoon, and together we went out to his apparatus, which he kept in a shed at the edge of the college hockey field. His balloon—the only one of the three he owned that was currently in working order—was a rather small one, capable of lifting about a hundred and fifty kilograms, including the basket. It was made of a single layer of ordinary silk, varnished after stitching, and no doubt leaked abominably. His methods of gas production were also primitive, although conventional for those days. He was obliged to produce his hydrogen on the spot by adding iron filings to a large earthenware flask of muriatic acid, and then to remove all traces of acid and other moisture from the product by passing it through a system of filters. The gas was then piped to the filling tube of the balloon, which had to be held in position by the three of us as it swelled and gradually assumed form. The whole process took a matter of three or four hours, broken by intervals in which it was necessary for Professor Eggert to uncap the flask and add more acid and filings. At last the balloon stood up like a soufflé with the basket underneath it, the whole prevented from rising only by the weight of a couple of bags of sand. The hockey players on the field, when they saw that preparations were imminent, stopped to watch us.

Then occurred an extraordinary and, as one looks back on it, quite childish confusion. It became clear only at this point that the balloon would carry only two persons, and the Professor had not thought out the practical arrangements to the point of deciding who these two were to be. He invited me to climb in, and climbed in himself, leaving Waldemer standing on the grassy field, still polite, still cheerful, but holding the basket firmly with one hand. Waldemer pointed out that he had come all the way out from Harrisburg on commission from his newspaper to describe the sensations of a balloon ascension and would suffer a monetary loss if prevented from doing so. This seemed reasonable to me and I climbed out. Waldemer mounted into the basket, whereupon the Professor climbed out and stood on the ground beside me; not out of any kind of displeasure or petulance, but simply because it seemed to him better, until these practical questions had been settled, for everyone to get out and discuss the matter calmly with both feet on the ground. Waldemer, however, was not easily persuaded to come down. Cheerfully, doggedly, and intelligently, reinforcing his position with logic, he clung to the basket of this celestial bicycle, which was soon to solve for him another of the anatomical flaws of man, his lack of wings. His well-modeled chin was set and it was clear he was not going to get down. What benefit could this ascension or any other ascension possibly have for mankind unless mankind became aware of it? And how could mankind become aware of it unless modern journalism disseminated its notice over the world? If this ascension was worth undertaking, it was only in that it might become part of the annals of man’s progress, and the custodians of these annals were those who converted ephemeral events into the permanency of print, i.e., himself, Waldemer, the other employees of the New York Herald, and their colleagues throughout the nation and the world.

It might be thought that Professor Eggert gave in to him out of weariness, but this was not so. In the end Professor Eggert was persuaded by his argument. In spite of his abstruseness, his scientific reclusiveness, he was not insensible to the benefits and even the necessity of publicity. He invited me to climb in, I took my place beside Waldemer, and Waldemer pulled the cord of the bursting valve in the belief that it was the rope that released the ballast. The silk bag gave a gasp, doubled inward at the centre like a man who has been stabbed with a dagger, and quite slowly began to sink down over us. The hockey players gave mock cheers. We had plenty of time to get out of the basket and join Professor Eggert before the balloon lay like a heap of discarded clothing at our feet.

Of iron filings there was a copious abundance, since central Pennsylvania is freckled with iron mills, but muriatic acid was expensive. I was forced to resort to my own pocketbook to buy another demijohn, which had to be brought out from Harrisburg in a wagon. In any case, the ascension was postponed until the next day, when everything in fact worked faultlessly and Waldemer and I soared for an hour over various neat farms divided into rectangles, landing finally in a rye field. Professor Eggert followed us in a shay drawn by an intelligent mare that had learned a good deal about the movements of balloons and was able to trace out their landing places with hardly any guidance from the reins. Waldemer proved to be a valuable and useful assistant on that occasion. He soon learned to tell the bursting cord from the ballast rope, and we made many ascensions together over the Pennsylvania hills. Eventually we surpassed in our knowledge the bony and devoted Professor Eggert who was our teacher and learned things about balloons that even he didn’t know. In fact, although erudite and assiduous, Professor Eggert was in the final analysis somewhat deficient in imagination. His obsession was the discovery of a means for the direction of motion of gas-suspended aerostats, to free them from the whimsy of the winds. He had tried vanes of various sorts, and here he was excruciatingly close to the solution, although he didn’t know it himself and this approach was generally scoffed at by theoreticians of the time. Giving up vanes as a bad job, he turned to pedal-actuated airscrews and to devices emitting jets of gas. I have no opinion on these expedients, although it is possible that they may prove workable at some time in the future. Some of his experiments were highly perilous, and while ready to trust his own life to these untested devices, he was unwilling to risk the lives of others, and frequently used animals as subjects in his researches. This led him into the complicated and exasperating difficulties of training cats to actuate gas valves and so on, a distraction which in my opinion interfered with the more important course of his discoveries. During my association with him, his thinking processes became completely stuck on the possibility of using aeromagnetism for steering purposes. He knew from my publications and others that electromagnetic lines of force curved symmetrically around the earth from pole to pole like a graceful feminine garment, and also that these fields were related in some elusive way to the electrostatic forces that produced lightning, St. Elmo’s Fire, and other paraphenomena of the atmosphere. I had many discussions with him on this matter. He argued that since the magnetic field consisted of lines of force, or at least was commonly spoken of in that way, there must be a force involved, and if a force existed, then there must in theory also exist the possibility of harnessing it for a useful purpose such as steering a balloon. I tried to convince him that the so-called lines of force lacked absolutely the power of pulling any object either north or south, and at the most they were capable of aligning elongated ferrous objects into a position parallel with themselves, as they did with a compass needle. But he contended, first of all, that if a compass needle is twisted, then a force has been applied to twist it, and this same force might at least in theory be used to twist a balloon. I pointed out that twisting a balloon was not the same thing as sending it off in a direction contrary to the wind, that he might twist the balloon until it spun like a top and it would still drift exactly with the wind in accordance with a dumb and inevitable law. Yet he could not give up the idea that the solution of dirigibility lay concealed somehow in the problem of turning the balloon at various angles to the wind. Here again—as my subsequent discoveries proved—he was prescient but insufficiently imaginative. He did, during the time I knew him, reach the point of sending up magnetized iron bars in balloons, on one occasion adding a barnyard fowl which he had trained to operate a mechanism locking the bars into place when the alignment was correct. Unfortunately, this experiment took place in the late fall on the verge of a storm, and a westerly gale blew the apparatus, as far as anyone could tell, toward the Atlantic coast and out to sea. It is possible that in an earlier age, the age of Franklin and Lavoisier, let us say, Eggert might have achieved a name for himself in the scientific world. But in the nineteenth century technology moved too quickly for him, and he was unable to surmount the problem of specialization that is the genius and the curse of our epoch. I felt a great sympathy for him, and I owed him a great debt and still owe him one for the tutorship he generously and quite selflessly offered me in aerostatics. Where is Professor Eggert now? Probably still at his state college, sending up ducks, kittens, and lady students in the antiquated airships of twenty years ago, and pursuing them over the countryside in his shay.

![]()

“Major, what are you thinking about so quietly there? Always falling into thought, you are. It’s your Scandihoovian mysticism.” This is his American form of humour, a badinage consisting mainly of jolly and bluff insults. “A metaphysical lot, you Swedes. Look at Swedenborg. You have too much time to think in the winter, that’s your trouble. Take the Norwegians. They have the same climate, but they spend the winter sliding around their hills on skis. They never think a bit. Look at ‘em, bursting with health.”

Actuating the string attached to the fuel valve so that the stove hanging below goes out, he pulls in the rope hand over hand and retrieves a perfectly brewed pot of coffee. This he pours into cups of a thick unbreakable variety selected by himself, and passes them to us, along with slices of coarse bread and butter.

“Ah.” He exhales contentedly. “Is the breakfast all right, Major?”

In actual fact I drink the coffee but find I have little appetite for the bread and butter. Not noticing this, he spreads his own bread thickly with butter and falls to. “Better than a poke in the eye with a sharp stick,” he comments in another widely applicable phrase of his. Still chewing, he gropes in his clothing for a handkerchief, removes a few crumbs from his mustache, and continues with the meal. Now and then he washes the bread down with a swallow of steaming coffee that produces another sound of satisfaction.

“There is something in what you say,” I admit. “But you oversimplify as usual. Swedes are quite possibly metaphysical in the winter, but they are hedonistic in the summer. Around Easter a transformation takes place. From then till autumn they’re as free from metaphysics as you Americans. They develop enormous appetites. They become amorous. I can assure you that in the summer a Swede never thinks at all.”

“But it’s summer now. Therefore, if your theory is correct, you shouldn’t be falling into thought.”

“Ah. But you see, it’s precisely from summer to winter that we are journeying. In Stockholm the air is balmy, on Dane Island it was brisk but still hardly cold, and now we are headed for ice and snow. In short, my dear Waldemer, space and time are interchangeable. Ordinarily it would be necessary to wait for several months for my metaphysical phase to come on, but we can produce the same effect at will by a geographical displacement.”

“Too deep for me. One of your paradoxes, I imagine. What’s this, Major, you’re not eating your breakfast.”

“I might, if we were headed south.”

“Very witty. Here, give it to me, I’ll finish it off.”

What is left of my bread and butter, the greatest part of it, to tell the truth, disappears into Waldemer. Then in a systematic way he sets about his morning ablutions. First it is necessary to answer the call of nature, which he accomplishes by means of the door in his underwear and a sanitary apparatus we have brought along for the purpose. Theodor finds something to look at in the other direction during this process. Then, after carefully washing his hands in a minimum of water, Waldemer turns to shaving. He fills a teakettle, puts it on the primus stove, and lowers the whole affair over the side again as in the business of coffee making, Following the rule prohibiting inactivity at any time, he brushes his teeth while waiting. The water is soon hot and the kettle below, with a kind of snoring noise, begins emitting a plume of vapour. He pulls it up, fills the shaving mug with hot water, and in a trice he has covered his face with foamy soapsuds. His straight razor he removes from a walnut case, tests for sharpness with his thumb, and holds poised over the waiting cheek.

“Ah.”

Something is troubling him. He looks in the toilet case, turns everything over, and assumes an expression of concern mingled with annoyance. “Drat it, I don’t seem to be able to find my pocket mirror. I was sure it was here.” He turns to me hopefully, apologetically, expectantly. “Major, I wonder …”

No, unfortunately I have not brought any mirror. I don’t intend to shave on this expedition, I explain, and I predict that he won’t either when he sees how difficult the process gets as we go farther north.

He turns to Theodor, but Theodor politely and regretfully shakes his head.

“Ah.”

Waldemer is perplexed. His face is covered with shaving soap, which is rapidly drying. The water in the teakettle is returning to the temperature of the atmosphere.

“H’mm.”

He takes a teaspoon from the provision basket, a bright and shiny new one, and tries unsuccessfully to catch his image in it, even the reflection of a small part of his cheek the size of a postage stamp, which he might shave and then pass along to the next piece.

“Bother!”

The spoon is far worse than those distorting mirrors at carnivals that send us back images of ourselves as dwarfs with three-foot foreheads. Waldemer is genuinely troubled at the lack of a mirror; if the expression were not out of character for him, I might say that he is metaphysically troubled. It is clear, if one observes him carefully, that his anxiety cannot be accounted for by his mere inability to shave. He could shave blind, by feeling with his fingers, or it would be possible for him not to shave at all. If he hurries, the water in the teakettle will still be warm enough for him to wash the soap from his face. No, Waldemer’s perplexity at the moment goes beyond shaving. What troubles him deeply is that there is nothing in the universe—since the universe for the present consists of the airship and its contents to reflect his image back to him and thus verify for him his own existence. If one looks in a mirror and finds an image reflected back, something must be generating the image, and this something is one’s self. It is not enough merely to feel your knee with your left hand, or bump your head against a wall. This sort of thing only proves that you are having sensations. But what is having sensations? Perhaps the sensations exist in themselves, hanging in a void, pretending to themselves that they belong to a person. A mirror represents confirmation from the external world. Naturally Waldemer if he chose could ask one of us whether he exists. “I say, old man, I am still here, aren’t I, and just the same? Or just about the same.” Thus the women who are continually asking if we still love them, or if they are pretty today, or if we like their dress. But it is typical of Waldemer that he has come to rely on a machine—since a pocket mirror is a tiny and simple machine—for a need that others satisfy through human relationships. Waldemer is troubled and I am not quite sure what is taking place in my own soul either. For I stole his mirror from his toilet case, last night in the shed, and hid it under the crate that served as our chair. It’s still there in the shed, no doubt, where Eliassen will find it as he found my pocket diary—which I left behind quite inadvertently, incidentally; no metaphysical motives there. “Ah, pity, Mr. Waldemer has forgotten his mirror. How will he shave?” How indeed? Why indeed have I been so furtive and so perfidious? I don’t know. Waldemer doesn’t know why he misses the mirror so profoundly and I don’t know why I stole it. I conclude—I prefer to conclude—that it was playfulness on my part. A mirror is a trivial thing and to be annoyed because one has no mirror is petty. It is a little joke, like cutting off a fellow’s suspender buttons. Without suspender buttons his pants fall down and he has no dignity. It is really an American form of humour, like Waldemer’s jolly bantering. Also, it gives me pleasure to know that there are no mirrors in the airship. What do I mean by that? I’m not sure. Perhaps that I have no need to verify my existence with a little machine, or perhaps that I prefer not to verify my existence. This little trait of mine, which I have just discovered, is perhaps dangerous, I am not sure. Perhaps not.

“Major, I wonder if I might borrow your sextant. The fact is that this infernal soap is drying at a dizzy rate. If I don’t get it off soon I’ll be caked with the stuff, like a Grand Guignol actor, for the rest of the trip. Drat me for being so stupid as to forget my mirror.”

The sextant is essential to our navigation in this enterprise, that is to say, to our survival. It is a Koerner of the latest model, modified through the addition of a mercury level for the purpose of establishing the horizontal plane in the absence of a horizon. Taking it carefully from its wooden case, I hand it to him. Waldemer has respect for the sextant. There is no danger that he will break it. Carefully—most carefully—he takes it in his left hand while holding the razor in his right, and shaves himself by observing the tiny piece of his cheek which is visible in the index mirror. Man, contriving instruments to measure the world, succeeds in taking the measure of himself. Or more simply: Man as Reflected by His Instruments. When Waldemer is done he returns the sextant to me and I put it back in the box. Then he pours the rest of the water, which is still slightly warm, into his hands and vigorously rubs over the shaved places. To finish he dries himself neatly with a towel and hangs the towel in the rigging to dry. It immediately freezes.

![]()

Through all this Theodor has said nothing. He has eaten his breakfast with dignity, retrieving each crumb and wiping his fingers afterward with a linen handkerchief, but all rather absentmindedly, as though he were scarcely noticing what he is doing. Now he has set the coffee cup aside and is gazing with intelligence off into the horizontal plane, where there is nothing whatsoever to be seen. Theodor has many fine qualities but he is not quite sure yet who he is. He fancies himself a poet, and in fact writes fairly decent poetry when he is able to surmount the influence of Heine, but he is also fond of military clothing. His parents—the parents of Luisa—consist of an American father, now deceased, and a mother who was born of mixed blood in the Portuguese colony of Goa on the coast of India. The two came together somehow in Paris, but this is a whole story in itself. The mother in many ways is an interesting person, although I can’t say I care very much for the Goans I have known. The combination of bloods, in my experience, produces little more than a medley of Portuguese excitability and Oriental sloth, the least attractive side of both races. The mother’s main contribution to the world has been to bequeath her complexion to Luisa. Or to Theodor; I forgot for the moment that I was thinking about Theodor. His complexion is a translucent olive, pale like the moon and yet in some way at the same time dark; exactly—come to think of it—like the moon, which also gives this impression of darkness. But unlike the moon, which suffers from various pockmarks, this complexion is flawless and of a single substance, like a fine china teacup. Moons, china, there are too many metaphors in all this. But persons like Theodor demand metaphors; they evoke them, so to speak, from the ambient atmosphere. His voice is clear and rather high, a voice that would be almost a soprano if it were a woman’s voice, but since it is his voice it merely sounds refined. Theodor is a person of considerable culture, particularly in science and in languages. In addition to English and Portuguese he speaks French flawlessly, Swedish only after wrinkling his brow a little, schoolbook German, and the Italian of a Swiss hotel clerk. With his dark eyes and long aristocratic Silva e Costa face he is strikingly handsome, especially when he is speaking French or Swedish. Why have I brought him along? Because he has studied aerostatics and can sight through a theodolite, and also, no doubt, because he can regale us with some poetry if things get dull. I am beginning to see that, in spite of careful plans, there are many doubts and ambiguities in what I have brought along on this expedition and what I have left behind; for example, that I have deleted a mirror, which is useful, but have brought Theodor, who is vulnerable to the accusation of being merely decorative.

Still, it is better not to be confused about anything so fundamental as the sexes. Theodor is a man among men, the beau ideal of a young adventurer, and in spite of his complexion he is inured to the common hardships of cold, discomfort, and fatigue. I have climbed the Aletschhorn with him over the glacier and he never asked for quarter, although my legs after a while pounded like hammers. He is as contemptuous of the needs of his own body as he is of other human beings. What does he love? I hardly know. Perhaps his clothes, perhaps his dead father, or even me, in his contemptuous way. It is curious that for all his beauté he never looks in mirrors. How does he confirm his existence? His existence is inside himself. He is indifferent to the fact that his complexion and his dark eyes were never made for these latitudes. There is something Persian about him, a languor of oases, an indolence, which he subdues or ignores with the contempt for physical discomfort inherited no doubt from his frontier father. His only delicacy is a modesty about the needs of nature; in these things he is almost girlish and retreats behind a canvas stretched across a corner of the gondola. Although Waldemer hasn’t noticed it he, Theodor, hasn’t shaved yet this morning and yet his cheek is as smooth as it was yesterday. There are some things to come still in his manliness.

![]()

This Prinzess, the third to bear her name, is enormous. She is at least four times as big as any airship I have ever had anything to do with. Or so it seems now, when the clutter and distraction of the preparation are behind us and we are left to ourselves in the gondola. It is almost two metres from where I am standing to where Waldemer is checking the bolt of his light .256 Mannlicher rifle. Two metres is not very much in a ballroom, but under these conditions it is unbelievably and luxuriously commodious. We stand on a light floor of laminated wood, fabricated according to a new American process, which is removable in sections and under which provisions and spare gear are stored. Circling the gondola at shoulder level is the instrument ring, on which thedolites, magnetometers, and other paraphernalia may be mounted as needed. Between the instrument ring and the gondola itself a set of canvas windbreakers may be fitted in bad weather; in fine weather some or all of these are removed. Everything is stowed neatly; there is room for the pigeons and even for Waldemer’s miniature darkroom. If we stretch our hands upward we can touch the bearing ring, a small but intensely strong circle of steel to which the converging cluster of rigging from the gas bag is attached, and from which, in turn, depend the guys that support the gondola. To the bearing ring are fitted the long bamboo poles which serve as yards for the sails, at present furled or rather drawn in on their rings like curtains through a system devised by myself. The gondola of wicker and Spanish cane, the bamboo spars, the hempen ropes stretching up over our heads give the impression of an antique sea vessel, a fantastic craft out of some print of the sixteenth century. Everything is stowed neatly under our feet or in bags attached to the bearing ring. The ballast of fine lead shot hangs to the outside of the gondola, each bag with its drawstring for releasing. A carefully planned and well equipped expedition, the whole paid for by the estimable and well-merited firm of Prinzessin Brauerei G.m.b.H. in Bremen, in return for the privilege of naming our craft and driving therefrom a beneficial notoriety; although this policy may turn back on them if our venture goes badly, so that the product of their brewing is associated in the public mind with doom rather than with the intoxication of success. I have in my pocket a clipping from an Austrian newspaper which I have carefully cut out and saved in my billfold, for what purpose I am not sure, perhaps to amuse myself in dull moments: ‘Jener Herr Crispin, der mittelst Luftballon zum Nordpol und zurück fahren will, ist einfach ein Narr oder ein Schwindler.” Probably I am a fool and a swindler, Herr Oesterreichischer-Zeitungsschreiber, but what business is it of yours? I am not swindling you. At the most the hardheaded German brewers, who understand precisely the risks they are taking. On the whole, to this heavy-handed Teutonic invective I prefer the humour of the American polar explorer who told a reporter, at the time of my visit to New York last year, which was attended with a good deal of publicity, “People who wish to arrive at the Pole by means of airships, steam carriages, trained polar bears, etc., are attention seekers rather than serious explorers.” Touché! He has me there! Peary himself, it seems, is planning an expedition to the Pole using dog sleds in the dozens guided by whole villages of Eskimos, probably because he finds it easier to train Eskimos than to train polar bears. He is right that I am not serious, I wish I could be, but blast! We will see who gets there first. If he does I will drink to him cheerfully. I forgot to mention that the managers of the Prinzessin Brauerei G.m.b.H., in addition to paying for the expedition, have also made us a gift of two dozen of their best bock packed in a hamper full of straw. We will drink these in time and so they too will serve as a kind of ballast, the bottles and eventually the liquid going overboard to compensate for the gradual loss of hydrogen from the bag. Our lives waver on these handfuls of gas and grams of weight.

![]()

I take the Koerner sextant from its case and point it at the coppery disk hanging in the east. Theodor watches the two chronometers, waiting for me to call out the exact moment of the observation. Looking through the sighting tube and slowly turning the screw, I bring the image of the sun in the index mirror down exactly to meet its twin floating in the mercury. Since the sun is still rising the two disks keep persistently trying to creep a hairline away from each other. Wait … wait … Now I’ve got them: “Allez … houp!”

Theodor writes down the time: 09h 06m 52s GMT. So on until five altitudes have been taken. I average these, discard one altitude which seems to contain an error, and set to work with my logarithms and almanac. In twenty minutes, with fair confidence, I am able to draw a position line on the chart, locating us at 80˚ 40’ north and 11˚ 32’ east, or some forty-seven nautical miles north-northeast of Dane Island.

I write this formula on a slip of paper, adding, “All hands well. Altitude 200 m. Proceeding north. Prinzess expedition, 0906 GMT 12 July 1897.” Then Waldemer unbuckles the wicker case under our feet and thrusts his arm in. There is a soft fluttering, some alarmed coos, and Waldemer’s arm emerges holding a grey and white pigeon with a pink bill. The pigeon twists his neck and flaps one wing a little, whether in alarm or in eagerness for the coming flight is not clear. I pass Waldemer the slip of paper and he rolls it tightly, screws it into a tiny aluminum tube, and fixes the tube to the pigeon’s foot, managing to do all this while holding the pigeon softly pressed against his chest. Then, with the pigeon perched on his right hand, he raises it and transfers it to the instrument ring in front of him. The pigeon looks around brightly with little jerks of his head and pecks at something on his shoulder. He seems content on the instrument ring and shows no inclination whatsoever to fly.

But Waldemer has learned something about the functioning of this particular mechanism. “Now then, darling.” He carefully extends his gloved forefinger and touches the bottom of the pigeon, about halfway between his virile parts and the place where his legs are attached. Like a clockwork bird whose lever has been touched, the pigeon soars into the air, his wings slapping loudly until he gathers speed and flies more smoothly. At first he dips lower; then he circles the Prinzess at a medium distance, climbing with white flashes of his wings, which beat faster and faster until they are too rapid for the eye to follow, a kind of optical twittering. Finally, gaining speed, he slides off on a tangent and soars away to the south. Smaller and smaller he becomes a dot, a winking pinpoint—and then he has disappeared. Waldemer, with an air of satisfaction, continues to stare in the direction of the pigeon for some time after he is no longer visible. This tiny speck of life, we hope, will make its way some eleven hundred miles to its home in Trondheim. No pigeon has ever flown so far or over so deserted and forbidding a sea, but perhaps this one will. There in the Norwegian fishing town the honest watchmaker and pigeon fancier who is his owner will find him huddled on the sill of the cote, trembling with fatigue. He will give him food and caress him, and he will pull the tiny slip of paper from the tube and take it to the telegraph office. Electrical currents will carry the words to the Aftonbladet offices, whence they will be disseminated by other wires and cables to Waldemer’s own newspapers, the London Daily Mail and the New York Herald. In this way the world will learn our exact location at nine hours and six minutes Greenwich mean time, provided the pigeon reaches his destination and a whale has not eaten the transatlantic cable. Sometimes a Physeter macrocephalus, or sperm whale, scooping krill from the sea bottom with his long jaw, will encounter a submarine cable and snap it like thread without noticing what he is doing. Sometimes, on the other hand, this swimming elephant gets his jaw tangled in the cable and drowns. This of course has nothing whatsoever to do with the Prinzess expedition and the pigeon on his way to Trondheim; it is simply one of many indications that the struggle between nature and civilization is not yet quite decided.

“Well, Major?”

“Well?”

“Thinking again, I see. And I can imagine what you are thinking about.”

He carefully does not make a roguish smile, but the signs of its suppression are visible behind the mustache.

“Can you?”

“The sight of the pigeon flying off. You know. Makes us think of … our—loved ones.”

“Loved ones?”

He thinks it is rather dense of me not to get the drift by this time. “Miss Hickman. Eh?”

I glance briefly at Theodor to see his reaction. No reaction at all. To judge from his face he might not even have heard; but of course he has heard. I decide to follow a mock-dignified and slightly offended line, calm but my chin raised just a fraction of an inch.

“You forget we are still travelling north. And the farther north we get, the less my thinking concerns itself with such—carnal matters.”

Waldemer really is embarrassed. The roguish smile emerges from behind the mustache; his defence is to treat the thing as a joke. “Well, Major. I wasn’t really referring to—h’mm. Carnal matters. It’s just that, you know. One’s more tender sentiments …”

“Whenever I notice any such, I go to a doctor. He gives me a medicine for them.”

“Ahah. Bravo, Major.”

![]()

Theodor, by way of ignoring this whole conversation, or pretending to, has been studying the chart, checking our course with the parallel rules and verifying the distance run by stepping it off with the dividers. His glance is intent on this crisscrossing track of pencil lines that begins at the camp on Dane Island, passes between Amsterdam Island and Vogelsang until it clears the Spitsbergen group, and then verges off northward onto the blank part of the chart. Finally, sensing I am watching him, he looks up.

“Well?”

For a moment he hesitates, afraid perhaps that with his lack of experience he has made some blunder in the calculations. “You can check whether I’m right, Gustavus. It seems to me our speed has averaged eleven and a half knots instead of eight. And we’re being deflected a little to the east.”

Standing in absolute silence at his side, so that our elbows touch, I pretend to check his figures. But I know without looking that he is right. I frown over this for a moment with my finger on the chart. After a while Waldemer notices that I have fallen into thought again, my Swedish vice.

“Something up with the weather?”

“I think so.”

“Still looks lovely. Not a cloud in the sky except for this infernal haze.”

“What is happening would be a long distance away. Invisible to your mortal eyes, I’m afraid.”

“Ahah. Perturbations in the ether. Well, you’d better consult the Spiritual Telegraph, Major.”

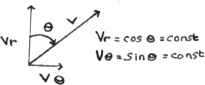

This is said in his usual tone of good-natured banter, but it is exactly what I plan to do. With a quickening excitement that I seek to control, or at least to conceal from my companions, I bend down and unstrap the lid of the leather case stored under our feet. Inside is the apparatus that has occupied my private thoughts for so many months, the climax of my investigations into the relation between aeroelectricity and geomagnetism that go back as far as the Greenland expedition of 1882. It consists of a coil of fine wire wrapped precisely around a fiber cylinder, a condenser made of tinfoil and waxed paper, and a crystal of galena over which is poised a tiny hairspring. The crystal is connected through a pair of insulated copper wires to the magneto-auditory converter, which to tell the truth is an ordinary telephone receiver manufactured under the Bell-Edison patents. Finally, there is the aerial coil or catching basket, consisting of more copper wire wound around a frame and rotatable through a pair of pivots. I erect all this and verify that the connections are tight. Then, holding the receiver to my ear with one hand, with the other I gently touch the hairspring to various points on the galena crystal.

The scrap of mineral is very tiny, no bigger than an English farthing, but over the months I have come to know every detail of its surface as the husband knows the body of the wife. There, next to that double ridge and in the pit no bigger than a flyspeck, is a particularly sensitive spot. The end of the hairspring descends with a tremble into this concave triangle, and in the earpiece I hear sounds until recently never apprehended by the ear of man. A rustling, rushing, crackling, hissing, rubbing, muffled cracking noise, like celestial bacon being fried. Adjustments of the coil and condenser slightly increase the volume of these sounds. What am I hearing? No one is quite sure. What is certain is only that these cryptic sounds have coursed through the atmosphere from the beginning of time, but have been audible to the human ear only in the decade—less, in the five or six years—since the development of the detection apparatus. Where they come from—what intelligence or blind force it is that sends them crackling and hissing on their way to us—is an enigma. But I think I have begun to guess. I have guessed that the cracklings are produced by the agitations of the atmosphere that we ordinarily refer to as weather. Weather consists of various collisions between airs of different sorts. Some masses of air are dry, some are wet, some are compressed and others rarefied. In this way, following the laws of physics, they drift about in relation to each other and shift their respective positions. The wet masses, becoming rarefied, lose the strength of their grip and release rain. The dry masses, becoming warm, ascend upward, and others rush in to take their place. The atmosphere is the battleground of invisible monsters. This is well known. But what is not well known—if my guess is correct and my discoveries are not the product of a disordered fancy—is that these lumps of warm, cold, wet, dry, and other kinds of air, by dint of rubbing against each other like huge animals, produce electromagnetic vibrations exactly similar to the cracklings and sparkings that result when sealing wax and fur, or silk and a lump of amber, are rapidly frictionated. Further, that these emanations are directional in nature. Should there be, for example, a rarefied air to the westward, the prevailing wind will be from the south. It is to the area of low pressure that the lumps of air rush most vigorously and begin circling in cyclonic pattern, causing the most collisions and therefore the most cracklings in the electromagnetic apparatus. It is possible that this is only a metaphor. Nevertheless, like those well-known metaphors that men in some ages have called gods, it works and can be understood if a man studies the manner of its interpretation. I believe it was Goethe who said, with a prescience only possible in a scientist who was also a great poet, “Nature is infinite. But he that will take note of symbols will understand all of it. But not altogether.” Or he said something like that; I haven’t the text at hand and have to rely on my memory.

Leaving poetry out of it, what are we to think of these emanations that seem to speak to us out of the invisible emanations that have all the attributes of occult phenomena and yet are detectable only by the latest scientific apparatus? Perhaps this is the sixth sense that men have pondered over in all ages, from the ancient to the modern, without understanding very clearly what they are talking about. Supposing you had no sense of smell—the idea of such a sense would hardly occur to you except through a sort of mysterious intuition. And this thing I have found is mysterious all right. I remember that August day in a pasture in Varmland when I first heard lightning—I don’t mean that I heard thunder, but that a half-darkened shed with the Edison receiver pressed to my ear I heard the crash of fire striking from a cloud still a dozen miles away, a full minute before the sound of thunder reached my ear. The lightning bolt had signaled its existence through certain mysterious vibrations; but vibrations of what? Something had vibrated, some fine gas our organs are too crude to detect had trembled at the stab of the bolt. What purpose can this shimmering of the ether have? Has it waited patiently, over the billions of years, for the moment when I happened to connect up my earpiece to the crystal of galena and became the first to hear it? If so its accents are a little cryptic. Perhaps I have only intercepted a message intended for someone or something else.

I will confess that this thing I have stumbled across fascinates me to the point of ecstasy, and also that it seems to me vaguely dangerous. Dangerous how? I don’t know. It is simply that there is an element of necromancy in all this which, in the privacy of my own mind, I quite candidly regard as ominous. If you go sticking your finger in nature’s private parts you do so at your own risk, and at the risk of all humanity. In the Middle Ages the alchemists, without understanding what they were doing, groped about with their cauldrons and retorts in an effort to turn lead into gold. Instead they discovered the principle of chemical combination, which in turn gave birth to gunpowder, and an entire civilization of castles and cathedrals crashed to the ground, the alchemists bleeding under the ruins along with everybody else. (It is true that gunpowder was invented by the Chinese, but I am speaking analogically.) It is characteristic of man that he is annoyed by secrets, that as soon as he is aware there is something to be known that he does not know he wants to know it, whether or not the knowing will make him happy. In the end it is perhaps this that will destroy him.

In the meanwhile, however, it is likely that we have a century or more to be happy or unhappy before this development takes place. Particularly in the case of aeromagnetic waves, it is unlikely that they will destroy us in the near future. On the contrary, it is probable that for a time they will be of great practical use. I am perfectly well aware of the investigations being conducted in this sphere by Hertz, by Signor Marconi, and by others. In my opinion these endeavours have every chance of succeeding. Consider: if static electricity is made to leap from one brass ball to another, the spark will cause a compass needle to be deflected in the room below, as much as thirty feet away. The fact was noted by Trowbridge as early as 1880. This being the case, there is no reason why, if the electric spark upstairs is interrupted in accordance with the system of Morse’s code, a message cannot be read downstairs on the compass, even though no wires connect them. Could such a contrivance work in an airship? Undoubtedly. Over long distances? Possibly. In no case am I going to hint of this to Waldemer. He has quite enough to occupy his mind as it is. If he ever suspected that the apparatus in the leather case might be used to send messages to the outside world, he would be composing drivel for it night and day. Including, no doubt, our “sensations,” such as the fact that our noses are cold and we are enjoying our dinners, and also our delight at the efficient functioning of the apparatus. This has already happened in the case of the ordinary telegraph worked by wires. A man sits in Chicago and taps out, “How well this telegraph works.” And the operator in New Orléans replies, “Yes, the telegraph is a great invention.” No, decidedly, the practical possibilities of aeromagnetism must be concealed from Waldemer.