17

Employee Engagement

It’s Not About the Employees

If you have read this far, you know that this whole book is about engagement. The concept of discretionary effort is about how to cause employees to want to give their best every day. This chapter will attempt to compare the performance management technology to other methods being sold today as ways to attain an engaged workforce—methods that I consider incomplete, wrong, or both.

In a commercial for Fiber One cereal, a woman pulls up by a Fiber One truck at a stoplight. She rolls down the window and yells to the driver, “I just love your cereal, there. It’s got such high flavor. There’s no way it is just 80 calories! Right? No way. Right?

The driver responds, “Lady, I just drive the truck.”

She continues, “There is no way! Right? Right?”

The driver, ignoring her question, says as he drives away, “Have a nice day.”

This reminds me of a story Paul Broyhill, of Broyhill Furniture, tells about himself as a young man working at the furniture company his father owned. One day one of their largest customers was in town and wanted to play golf, but Paul’s father was busy and asked Paul to play golf with the customer. As they were playing, Paul noticed that the customer was not recording his score accurately. After several instances of telling Paul an incorrect score, Paul questioned him, saying that he must have miscounted, and as he was recalling the shots, the customer shouted, “Are you accusing me of cheating?” and got in the golf cart and drove off. Paul walked back and reluctantly went to his father’s office. His father said to Paul, “Let me explain something to you, son. You thought you were playing golf, but you were supposed to be selling furniture.”

The driver in the Fiber Once commercial thought he was just driving a cereal truck when company executives also wanted him to be selling cereal. The driver in the commercial was not fully engaged in the business of Fiber One.

Jack Gordon, of Rubbermaid, was visiting a trucking company that had installed the performance management process when on one of the loading docks a forklift driver with a load of Rubbermaid merchandise stopped for Jack and his escort to pass. As Jack walked by, he noticed that the load was Rubbermaid products. He said to the forklift driver, “Be careful with that load, son. I work for Rubbermaid.

Without missing a beat, the driver replied, “I do too, sir.” This forklift driver appeared to be fully engaged in his work the way the trucking company wanted him to be.

Wouldn’t it be great if all employees responded this way? Well, they don’t. In fact, according to a Gallop survey, less than one-third of employees say they are fully engaged.1 What this means is that only one of three employees who see something that needs to be done but that is not explicitly in their job description actually does it. Because this is by the employees’ own admission, I suspect that the numbers are actually lower because there are likely some employees who are not engaged but do not want to admit that on a survey. Not only are the employee engagement numbers low, but they have been low for as long as they have been studied (1990s).

I don’t understand why, considering numbers like these, executives would not declare “corporate war” on disengagement. The amount of money “left on the table” as a result of this disengagement is significant. The organizational benefits for high economic returns produced by engaged employees are probably better than that of any other initiative a corporation can undertake. No matter what the initiative is, its success and the ability to sustain the gains are almost totally dependent on what people do and how they do it.

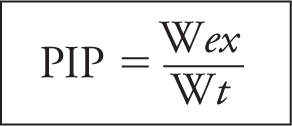

To get an idea of what is at stake here, Thomas Gilbert, author of Human Competence: Engineering Worthy Performance (Pfeiffer, 2009), developed a formula to measure the economic value of bringing out the best in people. He called it a measure of competence, and the formula shown in Figure 17-1 measures the performance improvement potential (PIP) in any job.

Figure 17–1 Performance improvement potential (PIP).

This formula enables the PIP of current employees to be calculated. Simply take the best performer’s production data, the exemplar, as Gilbert called her Wex, and divide that number by Wt, the typical or average performer’s production data, to get the PIP. For example, if the best performer Wex, makes 120 widgets an hour and the average is 90 Wt, the PIP 120 divided by 90 would yield 1.33, or a potential improvement of 33 percent.

When you convert these numbers to dollars, the economic value of moving every performer to the exemplar level is staggering. Of course, the skeptic will say that every employee can’t perform at the highest or exemplar performer level (I don’t believe that, by the way), but putting that argument aside, if you calculate the value of moving everyone, every shift, every team to the current average level, you will also be surprised by that economic benefit. Typically, the outcome is not a small number.

Another benefit of doing this is that the improvement is available for little cost because you are already paying for it but people are not being properly motivated to do their best. The distribution division of a major retailer was able to delay plans for constructing a new multi-million-dollar center because of increased throughput of existing centers. The increases occurred not by adding employees but by increasing output per employee.

The engagement goal should be to have 100 percent of employees delivering discretionary effort every day (fully engaged). And remember, the only way to accomplish this is through positive reinforcement. You cannot make people give you their best. Discretionary effort is given freely.

With all the work that has been done on various ways to create cultures of engagement over the last 20 years, why have the numbers not moved appreciably? Could it be that the current approaches to addressing the problem—and there are many—are missing the mark? In my opinion, the answer is “Yes.” One of the answers lies in the fact that the engagement data reveal that only one-third of managers are fully engaged. (Remember, this is by their own admission.)

I have often had executives ask, “Why don’t employees act like owners?” The answer is pretty simple. They aren’t owners. The more modern question is, “Why aren’t more employees engaged?” My answer is, “What is it about the workplace that would cause employees to want to get engaged?” We get engaged to people, not organizations. And there is the rub. If your manager is not engaged, why would a frontline employee want to be?

A not infrequent statement in many companies where employees respond to a supervisor after he has made a request of them is, “I will do this for you, but I am not doing it for the company.” While at some level “the company” doesn’t care what the employee says as long as the task gets done, I think everyone who has read this book to this point realizes that to have such a response from an employee is an indictment of company management rather than the employee.

One should ask how the employee developed such as attitude. Did he feel this way about the company from day one? If no, then what happened to cause him to feel as he does now? Obviously, some things have happened that the employee did not like. If employees are not engaged, it is a leadership problem. Nothing more, nothing less! Level of engagement is a reflection of the aggregate of management behaviors, decisions, policies, and procedures.

Current engagement approaches are typified in a free e-book produced by David Zinger entitled The Keys of Employee Engagement. In this e-book, 12 contributors present 26 keys (A–Z) with little overlap. They present over 300 ideas, and it is clear that they just made them up. By that I mean that they were not scientifically derived but came from the contributors’ experiences. I believe that we must move beyond personal experience to scientifically validated practices that work everywhere. Zinger describes many benefits to employees for being fully engaged in work, but the only problem is that they are all positive, future, and uncertain (PFU). This means that those who are not engaged are not likely to become engaged when the only consequences are PFU.

In addition, many articles and books about engagement suggest, outright or indirectly, that frontline employees have a responsibility to be engaged and help others to do the same. This is akin to saying that citizens in a country such as North Korea have a responsibility to make the government successful. Create a poor work environment, and employees will respond poorly. Create a proper workplace, and people will respond properly. Managers cannot share the responsibility for lack of engagement with employees. The relative lack of engagement is a reflection of the way people are treated by the environment managers create.

In the book Measure of a Leader (McGraw-Hill, 2007), my coauthor and I state, “The measure of a leader is the behavior of the followers.” Without major change at the leadership level of an organization, it is akin to the saying made popular by Sara Palin, former vice presidential candidate, “like putting lipstick on a pig”: the lipstick eventually wears off, and the pig is as ugly as before. A significant number of organizations have been using a lot of lipstick. Major surgery on how the organization treats people will be required for substantial and lasting improvement.

Contrary to popular opinion, the workplace creates a lack of engagement. It is not about attitude, communication, commitment, or flow. It is not about the employees at all. They can’t fix it. While some employees seem to be unaffected by the way business is conducted, even they can eventually be worn down to the point that they give little or no discretionary effort—doing their job and little more.

In order to have a more practical and effective solution to the problem of employee engagement (EE), I recommend changing from EE to ER—not emergency room but employee reinforcement. Engagement is about how to get people to willingly do everything in their power to move the organization forward at a rapid pace. There is only one way to do this. It is with positive reinforcement. Research confirms this fact, proven with literally hundreds of studies. While the average manager understands at a commonsense level that positive reinforcement is important, positive reinforcement is not well integrated into policies, procedures, and management behaviors. Reinforce at the wrong time, for the wrong behavior, in the wrong way, and at the wrong frequency, and you get not an energized, engaged employee but just the opposite.

Years ago, when I was training supervisors to lead employee teams, I told them that a good way to get a positive response from team members is to start the first meeting by asking the group for help in solving a work-related problem. In one of the first meetings, the supervisor gave the employees a problem that engineers, locally and corporate, had failed to solve. Quality consultants were hired, and they, too, had failed. The problem occurred intermittently, and despite hundreds of thousands of dollars spent over 18 months, it had not been solved. At the first team meeting, the supervisor told employees that he had a problem and needed their help to solve it. After he explained the problem, he asked if anyone had an idea about what was causing it. A team member spoke up immediately saying, “I know what that is.” It turned out that he did in fact know.

As I tell this story in some of my presentations, I ask the group, if the manager were to ask the employee, “Why didn’t you tell somebody?” what do you think the employee would have said? The students almost unanimously say, “Nobody ever asked me.” I have asked many groups this question for many years, and they always come up with the same answer: “Nobody asked me.” I recently asked a technician for our coffee service why a certain problem seemed to occur frequently. His answer, “I know how it can be fixed, but nobody ever asks me.” I am not saying that frontline employees have all the answers, although they may think they do, but they will never learn if they are not allowed to give input and find out if their suggestions do or do not work.

You might say that you have a suggestion system and employees have always been encouraged to make them, and because you get suggestions, you think the system works. When I wrote the first edition of this book, American employees produced two-tenths of a suggestion a year in formal suggestion systems. (I have joked that at that time it took five Americans to have an idea.) In Fuji Electric—the Tokyo plant I visited in 1981—there were 127 suggestions per employee per year, with over 85 percent implemented. Compared to the U.S. number of 0.2 per employee per year, the Fuji employees produced 635 times more ideas per employee than Americans. While this number is almost unbelievable, we might be surprised at what would happen if we simply began to ask a very simple question of frontline employees like “What do you think we should do?”

A new general manager of a mine I worked in gathered employees together on his first day and asked what changes were needed to make the mine safer. Although it took a while to get the first item, the suggestions soon began to flow because the general manager had the head of maintenance at the table with him, and when the first item was put forth, the general manager turned to the director of maintenance and asked, “Can you fix that today?”

The maintenance manager said, “We can start on it today.”

“Is there someone you can call and get started before this meeting is over?” the general manager asked. After he did that, the suggestions continued for over an hour. After the meeting, items that could not be fixed that day and those that needed corporate approval were posted on a chart on the general manager’s door and updated weekly so that employees could track the status.

When employees have a stake in the way things are done, they become fully engaged. If my idea is used, I have an interest in the outcome and will do my best to make it successful. When you ask employees for help, they are eager to help, particularly if they know that their input will be used or at least seriously considered. Engagement is not difficult. Just asking for input can change a person’s interest and actions about work.

As the general manager was leaving, after the meeting just mentioned, he asked a senior manager what he thought of the meeting. The senior manager replied, “Jim, I have always wanted to work in a plant like that, and now I do!” When employees’ ideas are listened to and when some are implemented, people become more engaged. How hard is that? How much does that cost? Whose permission do you need to ask employees for their help, ideas, or opinions? Apparently by the poor results for many years, some people are making this engagement thing into something that is difficult.

Many companies have given stock and stock options to make sure that employees are engaged. As you might imagine, stock and stock options are nice, but they don’t make much of a difference to employees after the day they are told about the award. As such, stock options don’t engage an individual day to day. Certainly all supervisors can ask for input not only on all problems but also on how to accomplish targets such as production, quality, safety, and costs. However, in the most engaged organizations, all ideas about the physical workplace, processes, systems, and work rules should be opportunities for input from the people who actually have to work in that environment and have to implement those processes, systems, and rules. Most of the time, employees are told what they have to do rather than how they should do it.

Every president featured on Undercover Boss always gets valuable input from the employees about things that would make the company better. Many times the “bosses” are stunned at how poorly company policies, rules, and processes are followed. They are also embarrassed at the negative impact their executive decisions have on the frontline level. Their ideas range from pay to security and personnel. Although it is a positive event that CEOs are willing to disguise themselves and attempt frontline jobs, it is a negative that they feel they have to do so to find out what employees really feel.

If you want to become a more positively reinforcing supervisor or manager tomorrow, you can start by saying the following many times per week: “I have a problem, and I need your help.” Most employees, when hearing this, will try to help you. They may not always be able to give you the help you need, but you will probably be surprised at how many times they will. In addition, when they can’t help, you will have an opportunity to teach them something about the business. Every time your boss asks you to improve some aspect of the business, be it budget, costs, production, quality, or safety, ask your employees for help. “We have to cut the budget. Can you help me?” When you are asked to implement anything, ask your employees for their help before implementing. You will be surprised at how smart they are and how engaged they become in the business.

A number of years ago, I took a group of CEOs to visit a trucking company that had created an outstanding engaged workforce. Everywhere there were examples of where employees went considerably beyond what would be normally expected. One driver went home to get his personal pickup to deliver freight because his large trailer truck couldn’t negotiate the snowy, icy roads that day. He had to make many trips to reload his pickup before all the freight was delivered. As the presidents were touring the shops, the shop manager was showing the CEOs a piece of equipment that one of the mechanics suggested would help improve the time it would take to rebuild engines. As Floyd, the shop manager, related the story, he said that when he heard about the piece of equipment, he presented a purchase request to his boss. His boss told him to do a return-on-investment (ROI) analysis on it. Floyd said proudly as he patted the machine, “They taught us to do an ROI, and here it is.” One of the CEOs said, “What does your purchasing department think of that?” Floyd took a deep breath, grew about two inches, and replied, “Sir, you are looking at the purchasing department.” That kind of engagement doesn’t just happen; it was a reflection of the culture that management created by design.

I hope you recognize by now that this book is really a manual for how to get total engagement. By implementing the principles and procedures presented here, you will be able to capture discretionary effort. Not only will you see large changes in organization or unit economic outcomes, but you will also make it a great place to work.

Notes

1. Amy Adkins, “Majority of U.S. Employees Not Engaged Despite Gains in 2014,” Gallop Employee Engagement Survey, January 28, 2015.