The traditional Japanese calendar was a great deal more complicated than anything we have known in the West. Also, because of yin-yang and related ideas, it was far more important in people’s everyday lives than even the medieval European calendar with its plethora of Saints’ Days, movable feasts, and other observances.

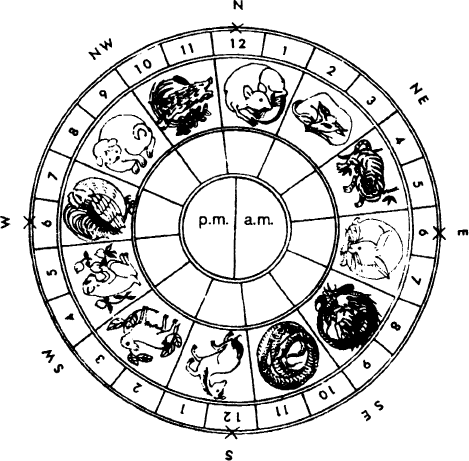

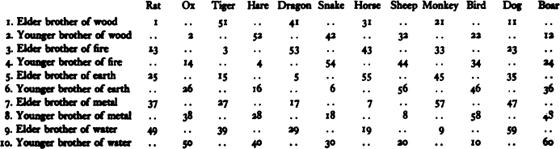

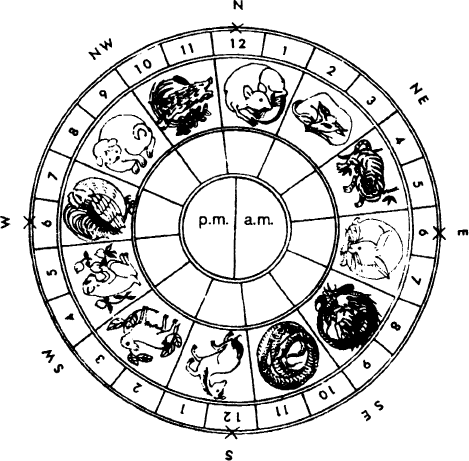

In order to explain as clearly as possible the calendar that dominated Heian activities, ranging from the appointment of high government officials to trivia like cutting one’s toe-nails, it is best to start with the Chinese Zodiac, which was the basis of dates, time, and directions. This diagram drawn by Mrs Nanae Momiyama, gives the following information from outside to inside: (i) the compass directions, (ii) the hours of day and night (midnight at the top, noon at the bottom), (iii) drawings of the twelve ‘branches’, each corresponding to one watch or two Western hours.

In order to designate a date the Japanese normally used a combination of two series, which produced a cycle of sixty days or sixty years, sixty of course being the first number divisible by both ten and twelve. The first series consisted of the twelve signs of the Zodiac as shown in the diagram. These signs, known as ‘branches’, were as follows: (i) rat, (ii) ox, (iii) tiger, (iv) hare, (v) dragon, (vi) snake, (vii) horse, (viii) sheep, (ix) monkey, (x) bird, (xi) dog, (xii) boar. They referred to (a) time (e.g. Hour of the Snake - 10 a.m. to midnight), (b) direction (e.g. Dragon-Snake - south-east), (c) day of the month (e.g. First Day of the Snake), (d) year (e.g. Year of the Snake - sixth year of any sexagenary cycle). At present the only frequent use of the Zodiac is to designate years: 1969 is the Year of the Bird, 1970 the Year of the Dog, and so on.

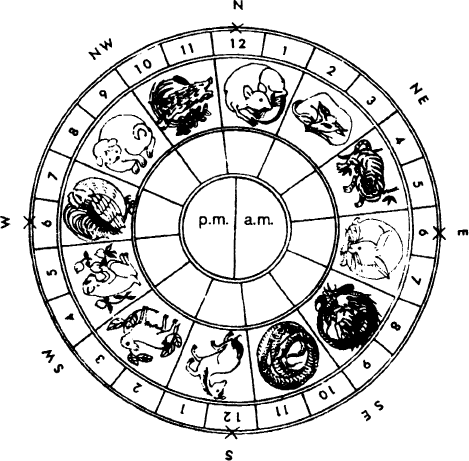

The second series consisted of ten ‘celestial stems’ which were produced by dividing each of the five elements into two parts, the ‘elder brother’ and ‘younger brother’. The ‘branches’ and ‘celestial stems’ were combined to produce the basic cycle of sixty (see opposite).

If, for example, a month started on the fifteenth day of the sexagenary cycle the third day of that month would be designated as: (i) the (first) Day of the Dragon, (ii) the (first) Day of the Elder Brother of Metal, (iii) a combination of (i) and (ii). In any given month there was a maximum of three days named after each of the twelve ‘branches’ and three days named after each of the ten ‘celestial stems’. These days could be identified by the prefixes ‘upper’, ‘middle’, and ‘lower’ for the first, second, and third respectively.

Years could also be designated in terms of year-periods, which were regularly decided by the Japanese Government from the beginning of the eighth century. This was an involved system of dating, because year-periods could begin in the middle of a calendar year and were often changed several times in the course of a single imperial reign; a further complication for the Westerner is that the latter part of the Japanese lunar calendar falls in the first part of the following year according to our solar calendar. Later Japanese historians made the year-periods retroactive to the first day of the first lunar month of the year in which it was adopted, but this in fact only served to complicate matters further.

The names of the months in pre-Heian Japan were far more evocative than our dull Januarys and Februarys. This is their literal translation:

1. Sprouting Month

2. Clothes-lining Month

3. Ever-growing Month

4. U no hana Month (the u no hana was a pretty white shrub)

5. Rice-sprouting Month

6. Watery Month

7. Poem-composing Month

8. Leaf Month (i.e. the month when the leaves turn)

9. Long Month (i.e. the month with long nights)

10. Gods-absent Month

11. Frost Month

12. End of the year.

Charming though many of these names are, I have avoided them in my translation for fear that they might produce a false exoticism of the ‘Honourable Lady Plum Blossom’ variety. Instead I have designated them by the numbers (First Month, Second Month, etc.) that are used in all the early texts of The Pillow Book. It should be understood that, though Tenth Month, for instance, was normally written with the characters for ‘ten’ and ‘month’, it was pronounced Kaminazuki, which means ‘Gods-absent Month’, and that it could also be written with the phonetic symbols representing ka, mi, na, zu, and ki. Months were either twenty-nine or thirty days long, with an intercalary month added about once every three years.

Days, as we have seen, were designated in terms of the sexagenary cycle. They could also be defined by their order in the month, e.g. Third Day of the Rice-sprouting (Fifth) Month. When reading pre-modern literature we should remember that there was a discrepancy, varying from seventeen to forty-five days, between the Japanese (lunar) calendar and the Western (Julian) calendar, the Japanese calendar being on an average about one month in advance of the Western. For example, the twentieth day of the Twelfth Month in 989 (the date when Fujiwara no Kaneie became Prime Minister) corresponded to 19 January 990 in the West; and the thirteenth day of the Sixth Month in 1011 (the date of Emperor Ichijō’s death) corresponded to 25 July. Accordingly the most important day of the year, New Year’s Day, came at some tune between 21 January and 19 February in our calendar.

The dates of the four seasons were rigidly respected. To wear clothes of an unseasonal colour was an appalling solecism in Sei Shōnagon’s society; a white under-robe in the Eighth Month figures among ‘depressing things’. Spring started on New Year’s Day; all the associations of New Year’s Day were therefore vernal, rather than wintry as in the West. Summer, autumn, and winter started on the first day of the Fourth, Seventh, and Tenth Months respectively.

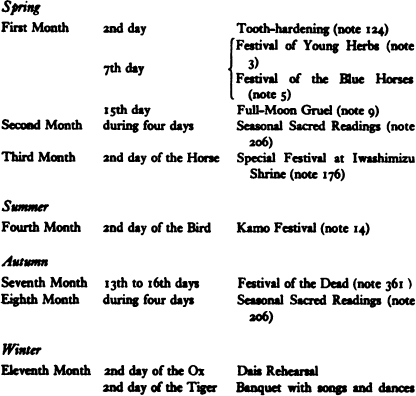

The Heian calendar was crammed with annual observances of all kinds. The five main festivals were New Year’s Day (first day of the First Month), the Peach Festival (third day of the Third Month), the Iris Festival (fifth day of the Fifth Month), the Weaver Festival (seventh day of the Seventh Month), and the Chrysanthemum Festival (ninth day of the Ninth Month). Other observances described in The Pillow Book were as follows:

Finally, the Heian day was divided into twelve watches, each two hours in length and divided into four quarters. Time was specified by the Zodiacal signs. The watch of the Horse, for instance, started at noon and continued until two o’clock in the afternoon; the fourth quarter of the Hone therefore corresponded to the thirty minutes between half past one and two o’clock in the afternoon.

I shall conclude with a single complete example. The fourth quarter of the watch of the Tiger on the fifteenth day of the Sprouting (First) Month in the Fourth Year of the Chōtoku year-period, in which the Elder Brother of the Earth coincided with the sign of the Dog, corresponded to about 6 a.m. on 15 February A.D. 998. And it was at this moment in history that a maid announced to Sei Shōnagon (p. 107) that her precious snow-mountain had disappeared.