ENCOUNTERS WITH MY HO-CHUNK ANCESTORS IN THE FAMILY PHOTOGRAPHS OF CHARLES VAN SCHAICK

Amy Lonetree

MY FIRST EXPERIENCE with the Ho-Chunk images by Charles Van Schaick happened in 1993, when I was an exhibit researcher at the Minnesota Historical Society. That summer, I had been hired to work on A Common Ground, an exhibit that highlighted six different communities from across Minnesota, including the Ho-Chunk Nation. As a Ho-Chunk citizen and museum scholar, my interest in the project was both professional and personal. The exhibit marked the first time that a Minnesota cultural institution had presented the Ho-Chunk Nation’s story, and I wanted to participate in presenting this much-neglected part of state history. As the primary content specialist for the Ho-Chunk exhibit, I was responsible for researching Ho-Chunk tribal history, especially the tragic treaty and “removal” period of the nineteenth century. I was also in charge of locating objects and images to include in the gallery.

As the summer progressed, one of my colleagues—a designer on the project—told me about a treasure trove of historic images of Ho-Chunk families located at the Jackson County Historical Society in Black River Falls, Wisconsin.1 These images were particularly compelling because of how and why they were made. Unlike the collections of Edward Curtis, who sought to capture images of a “vanishing race” for ethnographic and commercial purposes, these were photographs that Ho-Chunk families themselves commissioned for their own personal use.

So, off I went to Black River Falls. On a hot and sunny June day, Donn Holder, who was the president of the Jackson County Historical Society, greeted me and ushered me into a room with the images. Boxes upon boxes were brought to me. For the first time, I held images of long known but never seen relatives on both sides of my family. I was profoundly moved. The photos were loosely organized according to family, so I asked for both the Lonetree and Littlejohn boxes during my first visit. I will never forget the moment when I found them—individuals whom I have heard about all of my life, people whose names I carry and who are the source of the fierce pride I hold within me. Here they were—in their regalia or the clothing of the day, inside the studio, on the streets of town, or at powwow grounds, smiling or looking stoic and strong. In many of their faces, I saw the faces of other relatives I love. I couldn’t help but feel enormous pride in these ancestors, my Ho-Chunk family, captured in photographs almost a century ago. Seeing these images of my relatives led to a series of conversations with my grandparents, and through these conversations I came to know my own family history and tribal history in ways that strengthen me to this day.

As I examined the hundreds of images of Ho-Chunk families, my mind was heavy with the historical research I was immersed in that summer. The Ho-Chunk Nation suffered a series of forced removals during the nineteenth century, and a significant number of the images were taken just a few short years after the darkest, most devastating period for the Ho-Chunk. Invasion, diseases, warfare, forced assimilation, loss of land, and repeated forced removals from our beloved homelands left the Ho-Chunk people in a fight for their culture and their lives. We as a tribal nation—both those in Wisconsin and in Winnebago, Nebraska—have yet to come to terms fully with this history. Yet, in the wake of these devastating events, the Ho-Chunk people survived and managed to remain in Wisconsin.

Those survivors were staring back at me from photographs taken decades before, near the very spot where I sat in Van Schaick’s studio, now home to the Jackson County Historical Society. They reminded me of the strength, resiliency, and survivance of my Ho-Chunk ancestors. Survivance is a concept defined by Anishinaabe scholar Gerald Vizenor as “more than survival, more than endurance or mere response; the stories of survivance are an active response. . . . [S]urvivance is an active repudiation of dominance, tragedy, and victimry.”2 The word “survival” does not sufficiently encompass the great strength, courage, and perseverance that it took for our people to remain intact as a tribal nation in the face of violence, colonial oppression, and policies of ethnic cleansing.

When examining photographs of Native Americans, Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie reminds us that “one cannot understand the images until you understand the history.”3 What played continually through my mind as I looked at this powerful visual legacy were the words of my late Ho-Chunk father, Rawleigh Lonetree, who always reminded me that “we were the ones that they could not keep on the reservation.” His words conveyed the strength and sheer determination of my Ho-Chunk ancestors to remain and persist in our ancestral homeland despite removals to faraway reservations—qualities that are central to my identity.

The Ho-Chunk individuals in the photographs have a historical context; they are not nameless faces but survivors of ethnic cleansing and ongoing colonization.4 In the essay that follows, I will place these photographs in historical context by providing a brief overview of Ho-Chunk history. And I will focus particularly on the history of our nineteenth-century forced removals, which ended just a few short years before these images were taken. Just as these photographs have inspired me, I hope they will inspire other tribal citizens to conduct research on their families and tribal histories. Knowing our history through the lives of our ancestors opens a recovery process that is central to addressing the legacies of historical unresolved grief that persist in our communities. Through these journeys into our past, we can reclaim our history for current and future generations of Ho-Chunk people.

UNDERSTANDING THE VISUAL LEGACY OF THE PHOTOGRAPHS

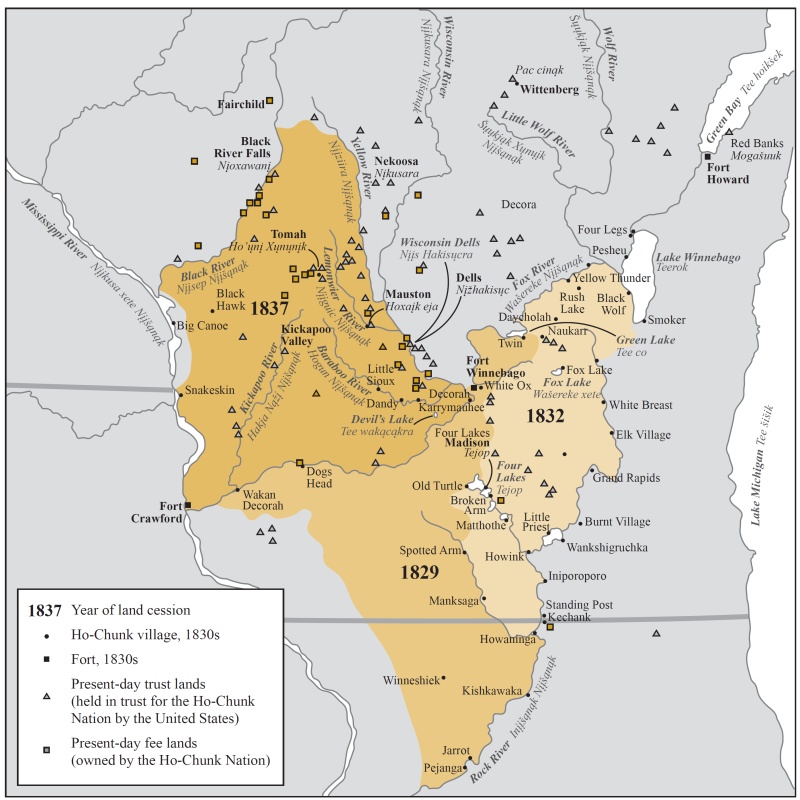

The Ho-Chunk are indigenous to present-day Wisconsin and have lived on these lands since time immemorial. Formerly known as Winnebago, the name given to us by outsiders, in 1994 we officially changed the name of our tribal government to Ho-Chunk, our name for ourselves. It means People of the Big Voice. Ho-Chunk claims to this land are deep and long-standing; we originated near present-day Green Bay, Wisconsin, known as Mogašuuc in our language, or the Red Banks. For countless generations, we occupied the lands in Wisconsin extending down into northern Illinois, and these lands bear the marks of our lives and the graves of our ancestors. Before the invasion of our homelands and the multiple land cession treaties in the nineteenth century, the Ho-Chunk occupied more than ten million acres of land in what is now Wisconsin and northern Illinois.5 After eventually acquiring almost all of that land, the U.S. government initiated a series of removals across four states that proved devastating for the Ho-Chunk, resulting in great misery and death. We are not sure how many of our people died during these removals or where they were buried.

The forced expulsions of tribal nations from their ancestral lands—at gunpoint and under the threat of extermination—during the nineteenth century to pave the way for westward expansion is typically referred to as the “removal period” in American history. Yet, this language obscures the devastation that this period brought. The invasion of our homelands, the heartbreak caused by the loss of lands that we as Indigenous people had occupied for hundreds of generations, and the killing of our people during these forced removals caused great suffering at the hands of the United States government.

These massive losses have never been fully acknowledged. Instead, much of the American public has chosen a willed ignorance of the devastating impact that this history has had on us. Using the more benign language of “removal period” to describe this history is but one example of this choice to minimize or erase the realities of this history. What truly happened—and what always should be remembered—is that deliberate acts of ethnic cleansing and genocide were committed against Indigenous people throughout the United States. It is difficult for Americans to accept that such brutality and inhumanity could happen in this country—more, that their privileged positions in our society today have everything to do with the attempted destruction of tribal nations. Difficult as it is, though, speaking the hard truths of this history is essential to moving forward in decolonizing the historical record and reclaiming Indigenous history.

It is also tragic that the specifics of the Ho-Chunk experience are not as well known or recognized as the experiences of other Native nations. We endured multiple land cession treaties and forced removals at the hands of the United States government, yet our history remains largely unacknowledged. I grew up hearing stories about my ancestors’ steadfast determination to return to our ancestral lands in Wisconsin in the wake of multiple attempts to keep us on a reservation in Nebraska. However, until 1993 I was not aware of the multiple attempts to remove us to reservations in Iowa, Minnesota, and South Dakota in the nineteenth century.

The photographs taken by Charles Van Schaick shortly after the most devastating period ended are a powerful visual legacy of the resiliency and pride that my father expressed. In order to understand the photographs, as Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie reminds us, we must understand the history. The very fact that we continued to exist as families and as a nation is testament to the strength and endurance of the people.

The loss of our beloved homelands began with the signing of the 1829 treaty. It was the first treaty that the Ho-Chunk Nation signed with the United States that included a major land cession. The land loss included our lead-rich lands in the southern part of Wisconsin and in northern Illinois. Before we even signed the treaty, waves of miners—close to 10,000 by the 1820s—began moving into our homelands, and neither the territorial or federal government did anything to stop the invasion. These early “settlers” and “miners” of Wisconsin committed depredations against Ho-Chunk people including theft and rape, leading government agent Thomas Forsyth to write in 1828, “[S]ome of the white people are insulting to the Indians and take liberties with their women, which the Indians do not like.”6 These early “settlers” also destroyed crops and reduced the hunting territory of the people, leading to extreme hardships and increasing hostilities between the invaders and the Ho-Chunk.7

A leader from the La Crosse band of Ho-Chunk, Red Bird, took a stand in 1827 against white encroachment onto Ho-Chunk lands. He initiated a series of raids against settlers and miners as they moved illegally into Ho-Chunk territories, but later surrendered to the Americans. Red Bird’s acts of resistance were not sanctioned by the Ho-Chunk leadership as a whole, but the United States government would later hold the entire tribe responsible for his attacks in order to secure a future land cession.8 While in Washington, D.C., Ho-Chunk leaders negotiated for his release. But the terms were devastating: the Ho-Chunk had to surrender their lands in the lead region. Tragically, Red Bird was never released from prison; he died of dysentery in 1828.

The Ho-Chunk were forced to give up their mineral-rich lands in the treaty of 1829. The Ho-Chunk “sold” 2.5 million mineral-rich acres in Wisconsin and Illinois to the U.S. government for the shockingly low sum of 29 cents an acre. Even by a conservative estimate, the land was valued at $1.25 an acre. Because of the sale, six hundred to seven hundred Ho-Chunk people were forced to move; most were members of the Rock River Band.9 The loss of the lead-rich land weighed heavily in the hearts and minds of the Ho-Chunk as leader Spoon Decorah stated, “[W]e never saw any of our lead again, except what we paid dearly for; and we never will have any given to us, unless it be fired at us out of white men’s guns, to kill us off.”10

In 1832, the United States forced the Ho-Chunk to the treaty table once again because of their alleged involvement in the Black Hawk War. The charge gave the government the excuse it needed to force the Ho-Chunk to give up lands south of the Fox–Wisconsin River portage.11 This treaty was the first signed after Congress’s passage of the 1830 Removal Act, a federal law that allowed for the wholesale removal of Native Americans from one land to another. The 1832 treaty with the Ho-Chunk contained a removal order: the Ho-Chunk were to be removed to land in Iowa, called the Neutral Ground, designed to be a buffer zone between the Sac and Fox and the Dakota Nations. All that remained of the Ho-Chunk lands in Wisconsin were located north of the Wisconsin River. The government acquired these lands in 1837.

The treaty of 1837 was signed in Washington, D.C., by twenty Ho-Chunk leaders, none of whom were authorized to negotiate a land cession treaty. In Ho-Chunk culture, only Bear clan leaders could enter into land negotiations; there were not enough Bear clan members of sufficient age and authority present in the delegation. Steadfast in their determination to keep what remained of our aboriginal homeland, the Ho-Chunk leadership made this maneuver intentionally to show their opposition to ceding land.12

Many of the treaties negotiated between Indigenous nations and the United States government were signed under horrific circumstances, but the signing of this treaty seems particularly egregious. After a long period of negotiation, the Ho-Chunk representatives were forced to sign away all of our lands in Wisconsin. The first article of the treaty states, “The Winnebago nation of Indians cede to the United States all their land east of the Mississippi river.”13 In a powerful quote, Ho-Chunk leader Dandy described what compelled the men to relinquish control of our homelands after long, painful negotiations: “[T]heir [Indian] agent told them . . . if they did not sign the treaty, he would . . . kill them.”14 At the time of the treaty signing, the leaders were also told that the Ho-Chunk would have eight years to move to the Neutral Ground in Iowa, but the treaty actually stated that we had eight months. Our removal out of Wisconsin began.

The first official order to remove the Ho-Chunk Nation occurred in 1840; investigations into the 1837 treaty negotiations had delayed the process by several years.15 A majority of the tribe was then forced from our homelands, and close to one thousand people died as a result of the horrific journey and poor living conditions on the Iowa reservation in the summer and fall of 1840.16 Our removal from our ancestral lands was brutal and heartbreaking. I cannot even imagine the pain my ancestors felt as they faced leaving their beloved homelands. A witness to the removal, John T. De La Ronde, relayed the following about the great sorrow of the people: “Two old women, sisters of Black Wolf, and another one, came up, throwing themselves on their knees, crying and beseeching Captain Sumner to kill them, that they were old, and would rather die and be buried with their fathers, mothers, and children, than be taken away; and that they were ready to receive their death blows.”17 Later, he came upon another Ho-Chunk group “on their knees, kissing the ground, and crying very loud, where their relatives were buried.”18

Our time on the Neutral Ground reservation proved to be short-lived. Fueled by their belief in manifest destiny and their “divine right” to settle the west, white settlers once again invaded our rich farming lands in Iowa. Following the signing of the treaty of 1846 that compelled us to relinquish the Iowa lands, the Ho-Chunk were removed to a reservation at Long Prairie in north-central Minnesota. Gull, a Ho-Chunk leader, expressed the ongoing heartbreak of the Ho-Chunk over these repeated removals: “We fear that our Great Father does not live in the fear of the Great Spirit or he would not ask us again to move from our lands. We have already given . . . a large and valuable portion of lands the Great Spirit gave us, and we greatly fear that his wrath will descend upon us if we move again.”19

Dissatisfied with the poor farming conditions on the Long Prairie reservation and the lack of access to the Mississippi River, the Ho-Chunk negotiated for a new reservation beginning in 1853.20 Ho-Chunk leader One Eyed Decora testified to the inadequacy of the Long Prairie reservation in 1855: “The brush is so thick we cannot get into it and if we could, the ground is so soft we could not stand upon it. There is no game in our country; it is fit for nothing but frogs, reptiles and mosquitoes.”21 In exchange for Long Prairie, the Ho-Chunk received land near the Blue Earth River in southern Minnesota following the signing of the treaty of 1855. This land proved more suitable for farming.

Almost as soon as we arrived on our reservation at Blue Earth, though, white citizenry began calling for our removal. The land at Blue Earth was fertile farmland and allowed us to have our crops and return to our seasonal agricultural activities. By all accounts, the Ho-Chunk at Blue Earth began to make a life on the reservation, following the preceding painful removals. For the most part, the Ho-Chunk were satisfied with the reservation, but our people faced serious attacks by the white citizens in the area.

One group in particular, the “Knights of the Forest,” organized for the sole purpose of seeking our removal from the state. In an article published in the Mankato Daily Review in 1886, one of its members spoke about the organization, claiming that many of the leading men of the city had been involved in this group. He discussed how their members would “lie in ambush on the outskirts of the Winnebago Reservation, and shoot any Indian who might be observed outside the lines.”22

Removal efforts only intensified after the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862, a war fought between the U.S. government and the Dakota Nation that left hundreds dead. Charles A. Chapman, one of the members of the Knights of the Forest, stated to the Mankato newspaper, “When the Sioux war was ended we saw that our safety from future massacres required the removal of all Indians from our neighborhood. Besides being a constant menace, they were occupying and rendering useless 234 square miles of the best farming land in Blue Earth county.”23 But the Mankato vigilante group was not alone in calling for our removal. A government agent at the time reflected the whites’ desire to rid the state of both tribal nations: “While it may be true that a few Winnebagos were engaged in the atrocities of the Sioux . . . the exasperation of the people of Minnesota appears to be nearly as great toward the Winnebagos as toward the Sioux. They demand that the Winnebagos, as well, . . . be removed from the limits of the state.”24

Although official government reports later confirmed that the Ho-Chunk remained on the reservation and had not participated in the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862, Minnesota’s ethnic-cleansing policy called for the removal of both tribes from the southern part of the state. In 1863, both nations were sent to the Crow Creek Reservation in South Dakota. Close to 2,000 Ho-Chunk made the brutal journey, and more than 550 people died on our forced migration out of the state of Minnesota. John Blackhawk, grandson of Chief Coming Thunder Winneshiek, recounts the brutality of the removal:

There are some few survivors of the band of that time still living, who went through those terrible days and shudder at the thought of them, when they were the helpless prey of the ruffian soldiers. Women and girls raped, men murdered, and all subjected to every insult and indignity that brutal men could invent. These outrageous things were inflicted upon the hapless victims for no other crime whatever except that they had been unfortunate enough to be born Indians.25

Crow Creek was a place of death far away from our ancestral lands—a place so horrible that my ancestors immediately began cutting down cottonwood trees to make dug-out canoes so they could flee. In 1865, the survivors moved to a new reservation in Nebraska near the Omaha Nation. This would become our last reservation. Tribal leader Baptiste Lasallieur recounted in 1863 the living conditions at Crow Creek that led to the mass exodus out of South Dakota: “We are not afraid to die, but we do not wish to die here. This country is unhealthy. All our people are becoming sick—our children and old people are dying every day. Father, never before have we had so many get sick and die. . . . If we stay here long, we think we will all die.”26

Throughout these “removals” across four states, groups of our ancestors kept returning to Wisconsin, even though it meant living as “fugitives” in our homelands. Between 1840 and 1874, the government made various attempts to remove these determined ancestors to the Ho-Chunk reservation of the moment.27 In 1874, the U.S. government’s attempts at expelling us from our beloved homelands finally ended, and in 1881, legislation was passed that allowed the Ho-Chunk people to remain in Wisconsin.

That same year, the government created a census roll of Ho-Chunk living in the state. This roll has become the “base roll” according to which citizenship in the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin is determined today.28 Many of the relatives listed on this “base roll”—survivors of the ethnic cleansing policies of the nineteenth century—are seen in the photographs of Charles Van Schaick’s collection, now housed at the Wisconsin Historical Society and reproduced in this volume.

BLOOD MEMORY AND PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGES: THE LONETREE AND LITTLEJOHN FAMILIES

During the summer of 1993, I was immersed in researching this history while I was working on the Common Ground Ho-Chunk exhibit. Needless to say, this brutal, tragic past was foremost in my thoughts as I engaged with the photographs. These images are also of great personal importance, given the many conversations I had with my grandparents, Ann and Samuel Lonetree, and other family members in the summer of 1993. After I returned to Minnesota from Black River Falls, I shared with family members the photographs I found of our relatives (and in my grandmother’s case, one of her). Photographs have the power to inspire conversations, clarify genealogical and historical information, recall anecdotes and humorous stories, discuss painful truths, and help us connect past and present.

One of the images that I discussed with my grandparents that summer was of my great-great grandfather Alex Lonetree. His Ho-Chunk name has become our family surname, and he is listed on the official tribal census roll of 1881. Alex is the son of Dave Tohee and Mary Hill, and he married Kate Winneshiek, daughter of John Winneshiek and granddaughter of Chief Coming Thunder Winneshiek. The Chief was the leader of the Ho-Chunk during the period of our forced removals in the nineteenth century. Repeatedly in the government documents, I came upon his words as he fought for our very survival as a nation. Alex and Kate’s son is my great-grandfather, George Lonetree, who also had several portraits taken with friends and family at the Charles Van Schaick studio over the years. In all of these images George is shown wearing the clothing of the day, unlike his father, Alex, who had a majority of his photos taken in his regalia.

My great-great-greatgrandfather, Alec (Alex) Lonetree (NaENeeKeeKah), ca. 1910.

In this image, my great-grandfather, George Lonetree (HoonchXeDaGah), left, is seated next to Robert Greengrass (HoNutchNaCooMeeKah), ca. 1920.

The portrait of Alex shows him in the center of the frame—a stocky man with a square wide face—wearing intertribal Native dress, including a floral bandolier bag across his shoulder. While others have identified his items of clothing as “Potawatomi leg bands, Chippewa bandoleers, and Arapaho moccasins,”29 what stood out for me was having the opportunity to hold an image of the person whose name I carry and through whom my citizenship in the Ho-Chunk Nation is traced and recognized. The conversations with my grandparents clarified my genealogy that summer and reminded me how deeply and inextricably linked my personal family history is to the history of the Ho-Chunk Nation. I have heard repeatedly in Indigenous communities that family history is tribal history, and knowing exactly who you are and where your relatives come from is a source of strength and pride that no one can ever diminish.

One of the other images that I shared with my grandparents that summer—and one of my personal favorites—is of my grandmother, Ann Littlejohn Lonetree, standing with her sisters, Florence Littlejohn Lamere and Mary Littlejohn Fairbanks, around their mother, my great grandmother Rachel Whitedeer Littlejohn. I absolutely love this image. While other images of Rachel exist in the Van Schaick collection, this is the only one taken with her daughters. I remember fondly the look on my grandmother’s face when she saw the photograph again many years after it was taken. Always a quiet, dignified woman, she smiled when she saw it, and her eyes lit up. She promptly told me who each of the individuals were in the frame, the proper spelling of their names, and what she recalled of the day when this photo was taken. While many people plan extensively for a studio portrait—deciding who should be included, what to wear, and how to style one’s hair—my grandmother said that they had this portrait taken on the spur of the moment. They found themselves in Black Rivers Falls, decided to go into Van Schaick’s studio, and then had the photo taken on the spot. I love the expressions on their faces and the contemporary feel of the photo. These are proud, attractive women, gazing straight into the camera and standing tall around their mother.

My great-grandmother, Rachel Whitedeer Littlejohn (ENaKaHoNoKah), front, with daughters Florence Littlejohn Lamere (HoonchHeNooKah), left, Mary Littlejohn Fairbanks (WeHunKah), and Ann Littlejohn Lonetree (WakJaXeNeWinKah), ca. 1930.

Several generations of the Lonetree and Littlejohn families are represented in the Van Schaick Collection. Seated from left to right are my great-aunt, Margaret Whitedeer Littlesam (NauChoPinWinKah), and my great-great-grandmother, Emma Stacy Whitedeer Lowery (HompInWinKah), sister and mother of Rachel Whitedeer Littlejohn. Standing between them is Lee Dick Littlesam (HaNotchANaCooNeeKah), ca. 1898.

For me, one of the most significant aspects of the Ho-Chunk photographs is that, while they were taken during the so-called dark ages of Native history, their existence provides visual proof of our presence. The images challenge the commonly held view that nothing of significance happened once Native people were confined to reservations in the nineteenth century, until the American Indian Movement’s militant activism captured the public’s imagination in the 1960s.30 The photographs taken by Charles Van Schaick are an invaluable resource for Ho-Chunk people as we begin to document more fully our tribal history during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The images give us a sense of what life was like for our families and people during this period. The so-called dark ages of Native history are no longer as dark. This collection of photographic images powerfully conveys the importance of kinship, place, and memory, as well as ongoing colonialism—all central themes of the Ho-Chunk experience during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Every encounter with the images should begin with the recognition that you are not just looking at Indians; you are looking at survivors whose presence in the frame speaks to a larger story of Ho-Chunk survivance.