IN HO-CHUNK CULTURE children hold a very special role. They will be the keepers of the culture, language, and ceremonies for generations to come. Children are shown love by everyone, in particular parents and grandparents. Traditionally, parents rarely scolded or punished, and never hit their children. Instead, discipline was administered by the maternal uncle (Teega) or a male cousin, usually by talking, scolding, or throwing water. In traditional families a child is made to fast when he or she misbehaves.

A child is taught at an early age the Ho-Chunk values of caring and generosity to others, and that everything they do is for the community and not the individual. As the child grows older, they learn they must develop a strong mind, a strong body, and a strong sense of responsibility to their family and clan. With a strong mind they are able to learn from the world around them and become good at solving problems, enabling them to accomplish tasks without being asked.

Traditionally, before a child was born, a male relative would construct a cradleboard for him or her. The cradleboard was decorated with small bells, side-stitch beadwork, and silk or bead appliqué Today as in the past, when a child is born, they receive a birthorder name such as Kųųnų, which means first son, or Híinų, which means first daughter. Traditionally, when a child was able to walk on the earth, a feast was held and the child was given an Indian name by a clan leader. Even today when a child is given their Indian name, it is a cause for celebration.

Throughout history, many Ho-Chunk children and infants were lost to smallpox, influenza, disease, and complications during childbirth. This made the birth of a child even more significant. With the creation of Indian boarding schools, many children were sent to schools in Wittenberg or Tomah, both in Wisconsin, and as far away as Kansas and Pennsylvania. With children living away from home, it was increasingly difficult for them to continue the language and culture of their ancestors. The Indian schools at Wittenberg and Tomah were some of the only schools in the country that allowed the children to speak their native language outside of the classroom. Despite the United States government’s attempts to rid the Ho-Chunk of their language and Indian ways, the Ho-Chunk managed to hold on to their traditions.

Today the Ho-Chunk are teaching the Hoocąk (Ho-Chunk) language to their children. This is the first generation in more than fifty years to become fluent speakers. For some children, Ho-Chunk is their first language, spoken at home and in daycare or school immersion programs. This new generation of native speakers will enable the traditions, culture, ceremonies, and Ho-Chunk way of life to continue.

Mabel Mary Lonetree (ENooGah) was the oldest daughter of Alec (Alex) Lonetree (NaENeeKeeKah) and Kate Winneshiek Lonetree (WauKonChawKooWinKah), ca. 1904. Mabel died in 1906 at the age of five from influenza. Her mother had died of the disease four years earlier, as did Mabel’s sister Anna in January of 1905 and her brother Howard one month after her. George Lonetree (HoonchXeDaGah) was the only child of Alex and Kate Lonetree to survive the epidemic.

This unidentified child is supported by a woman hiding behind the chair, ca. 1895. Her hands are visible on his arms.

John Stacy Jr. (HaGaKah) is propped up on pillows to keep him steady for the camera, ca. 1901. John Jr. was the son of John Stacy (ChoNeKayHunKah) and Martha Lyons-Lowe Stacy (KaRaChoWinKah).

Two young girls display their strands of bugle beads, ca. 1885. The girl seated on the floor has a Hudson’s Bay trade blanket on her lap.

A young Ho-Chunk girl is wearing a blouse that is completely covered in German silver brooches (hiiwapox) and has silver coins attached to the bottom, ca. 1895.

Two unidentified boys dressed in contemporary clothing, ca. 1910.

The children of Frank Lewis (HaNaCheNaCooNeeKah) and Addie Littlesoldier Lewis Thunder (WauShinGaSaGah), ca. 1905. George Bryan Lewis (PatchDaHeKah), left, is seated next to Amelia Emma Lewis (PatchKaRaWinKah), who is holding her brother Harry Ben Lewis (HooNaChaWeKah). To her right is Mary (Pinkah) Lewis (KeSaWinKah).

An unidentified boy with German silver earrings stands next to a younger boy who has been draped with a shell necklace, ca. 1890.

The children of Chief George Winneshiek (WaConChawNeeKah) and Rachel Funmaker Winneshiek (HockJawKooWinKah), ca. 1908. From left to right are Ellen Ella Winneshiek (TaCooHayWinKah), Clay Winneshiek (HunkMeNunkKah), and Fannie Winneshiek (HoChunkEHoNoNeekKah).

Martha Waukon (WeHunKah) wears a large wampum necklace and stands next to a chair with a floral appliqué blanket draped over it, ca. 1890.

Mabel White Blackhawk St. Cyr stands next to a young girl. The girls are dressed in their finest outfits. The youngest is seated next to a Ho-Chunk blanket with a silk appliqué “beaver tail” design.

Nellie Winneshiek Twocrow Redcloud (WaConChaWinKah) with her older sister Kate Winneshiek Lonetree (WauKonChawKooWinKah), ca. 1901.

Stella Blowsnake Whitepine Stacy (HayAhChoWinKah) is seated holding her two daughters, Josephine Whitepine Mike (AhHooGeNaWinKah), left, and Lena Whitepine Shegonee (HaCheDayWinKah), ca. 1907. Stella is also known as Mountain Wolf Woman, which is the title of a book written about her by Nancy Lurie.

Bertha Greengrass Blackdeer (HaukSeGoHoNoKah) holds her niece, Bernice, the daughter of Ruth Greengrass Cloud, ca. 1933.

William Crow (HaHiKaw), left, and Francis Cassiman, ca. 1920.

Esther Dora White Yellowbank (HoChunkEWinKah), the daughter of Ulysses White (HoZheWaHeKah) and Queen Redwing-Winneshiek (Fannie Winneshiek) (WarConJarUKee), ca. 1908.

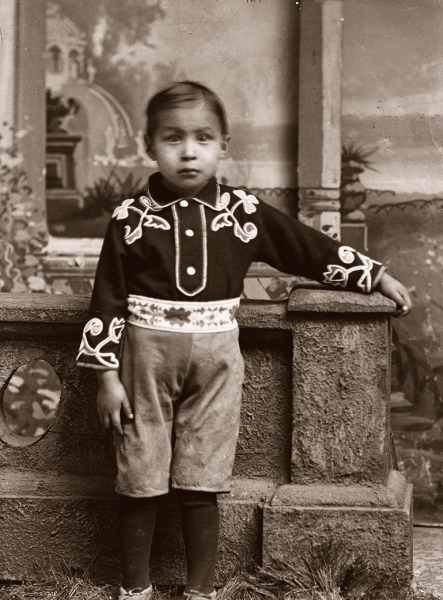

Edwin (Ed Jr.) Greengrass (HoonkSepKah) rests his arm on a wall in Van Schaick’s studio while wearing a floral beaded shirt and beaded belt, ca. 1900.

In this photograph taken near the end of Van Schaick’s career, Mary Edith Wallace Vasquez wears a Ho-Chunk woman’s outfit with a very rare floral beaded skirt, ca. 1940.

Liola Browneagle (WeHunKah), left, and her younger sister Maude Lookingglass Browneagle (ENooKah), ca. 1903. Liola and Maude were the children of Frank Browneagle (HeWaKaKayReKah) and Annie Snake (KhaWinKeeSinchHayWinKah).