VIETNAM IS A NARROW SLICE OF LAND THAT WRAPS LIKE A GLOVE around the bulge of the Southeast Asian land mass on the western side of the South China Sea. In May 2014 China put down a hostile marker against Vietnam, much as it had with the Philippines two years earlier at Scarborough Shoal.

The two countries share an eight-hundred-mile long land border across which they fought a war in 1979, and they have an antagonistic history going back centuries. From 111 BC to 938 AD, China colonized Vietnam, and successive generations have never been allowed to forget it. Vietnam has been run by its Communist Party since 1930 and was founded in its original form by the country’s charismatic father figure, Ho Chi Minh. Along with Che Guevara and Mao Zedong, Ho became a poster icon for the left-wing antiwar and free love populism that swept the West in the 1960s. Like China, Vietnam is a one-party state that represses free speech, jails dissidents, and holds power while embracing the Western capitalist model to develop the country. Almost a hundred million people live there, with a per capita income of only sixty-four hundred dollars, far behind China and even less than the Philippines. Vietnam is getting richer more slowly than it might because it spent a half century at war and a couple of decades after that isolated by the United States and the international community.

Beijing’s marker came shortly after building began in the Spratly Islands. It targeted waters some five hundred miles to the west, south of the Paracel Islands, which Vietnam claimed were within its two-hundred-mile exclusive economic zone. China countered they were within its Nine-Dash Line. The China National Offshore Oil Corporation brought in a massive nine-thousand-square-meter drilling platform, the thirty-six-thousand-ton Haiyang Shiyou 981, and started oil exploration. This was the same company that would have been given preferential treatment had the agreement with China, the Philippines, and Vietnam got through the Philippine senate. Open clashes broke out at sea, involving fishing crews and coast guards from both sides on dozens of boats and the sinking of a Vietnamese vessel. The platform left the area in August 2014 since, China said, it had successfully completed its work. Whatever oil reserves might have been discovered counted for little against the rupture in the Sino-Vietnamese relationship that Beijing had forced to a different level by deliberately throwing down a hostile challenge.

And it did not end there. In July 2017 Repsol, a Spanish oil exploration company under contract to Vietnam, was abruptly told to stop drilling days after confirming the existence of a major gas field. Repsol executives said that China had threatened to attack one of Vietnam’s Spratly Island bases if it did not pull out.

China might be bigger, richer, and more powerful, but Vietnam has a stubborn warrior streak that has been employed many times before, not only against China but also against France and the United States. Vietnam is the only country to have taken on these three permanent members of the UN Security Council in open warfare and won. Of all the countries of Southeast Asia, it has a track record of prioritizing national dignity above the economy. This was not Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, or even the Philippines. China had stepped across a line to provoke an ancient enemy. Officials in Beijing explained that they had to ratchet up the pressure when it came to Vietnam because in Southeast Asia it was traditionally “the most difficult country to teach.”46

In Vietnam itself, the government encouraged anti-Chinese demonstrations that scorched buildings and destroyed factories until the rioting began slipping out of control and became protests against the repressiveness of the Vietnamese one-party state. Three hundred businesses and factories were attacked, but only about two dozen were Chinese. Most were Japanese, South Korean, and Thai, indicating a general pent-up anger. The confrontation also exposed a modern truth: China was now a global power and it was a neighbor breathing hard down Vietnam’s neck. Vietnam had put up a plucky fight around the Paracels, but it had not won. Strapped for money, the Vietnamese Coast Guard and military were no match for the Chinese. Therefore, Hanoi needed to bury hatchets and get clever. It began by reaching out for help to the very country that had terrorized its people with helicopter gunships and burned its villages and countryside with napalm. It was a meeting of minds. The United States needed Vietnam’s help too. A year after the rig confrontation, Washington, DC, lifted its decades-long arms embargo. It gave Vietnam an $18 million loan for six forty-five-foot US-built coast guard patrol boats. F-16 fighters and P-3C Orion maritime surveillance aircraft were in the pipeline together with other military hardware from the British, French, Indian, Japanese, and other governments. Beijing’s show of force in oil exploration led directly to the strengthening of the anti-China pro-Western alliance.

Given Hanoi’s system of government, the alliance was in no way ideological and Vietnam found itself once again inside an incomprehensible twist of international diplomacy. Throughout the 1970s and 80s, this was one of the world’s most closed countries. Visitors spoke about going into Hanoi as they spoke of Pyongyang in North Korea, not going to as we would with London or Washington. They needed letters of introduction, visas, money, and flight bookings. The country was so heavily sanctioned that it flew only old Russian planes. Barely a vehicle plied the streets. As journalists, we sent stories via telex, from a central post office smelling of damp, rotting wood and disinfectant down by the Hoàn Kiếm Lake. We often ate supper in an illegal family restaurant in a magnificent, crumbling old house that served eel soup and baguettes, washed down with foul Bulgarian wine procured from one of the many flourishing black markets. A daughter played Chopin and Debussy on an out-of-tune upright piano, and a son kept vigil by a window.

Vietnam was under international sanctions because it had beaten the United States in the war. It faced a running issue of returning the remains of American servicemen missing in action, one of those situations that can be kept going indefinitely. The sticking point then was that the United States wanted to search the countryside with helicopters. “How could we do that?” a senior foreign ministry official had told me. “Can you imagine the trauma of our people if they see American helicopters flying above their villages again?”

Vietnamese fisherman, Vo Van Giau, beaten with a mallet by the Chinese coast guard.

(Photo: Poulomi Basu)

Author on assignment on Taiwan’s Dongsha Island.

(Credit: Simon Smith)

Vietnam lays a trap for Chinese warships in 948 A.D.

(Photo: Vietnam Military History Museum)

Concrete stakes on Kinmen Island to impale invading Chinese paratroopers.

(Photo: Humphrey Hawksley)

A Taiwanese military transport plane approaching Dongsha Island.

(Photo: Humphrey Hawksley)

Isaac Wang on Kinmen Island. In 1978, he was a psychological warfare officer.

(Photo: Isaac Wang)

Old Japanese gun position on Taiwan’s Dongsha Island.

(Photo: Humphrey Hawksley)

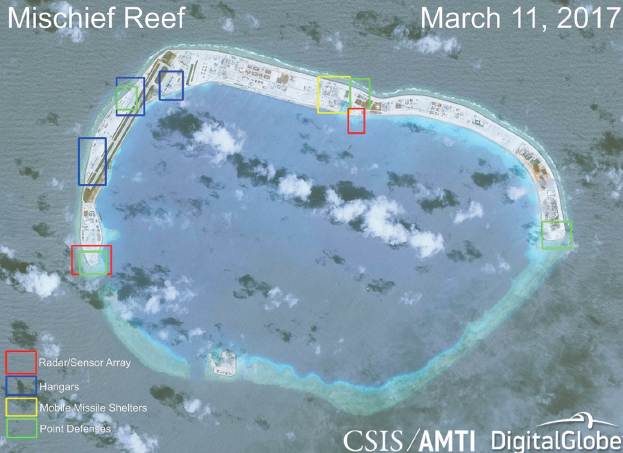

Mischief Reef in January 2012.

(Credit: CSIS/AMTI/DigitalGlobe)

Mischief Reef in March 2017 after Chinese military construction.

(Credit: CSIS/AMTI/DigitalGlobe)

Chinese naval officers visit the US Naval War College in June 2017.

(Credit: USNWC)

Inexplicably, Vietnam was also under sanctions for ending the genocide carried out by the Khmer Rouge in neighboring Cambodia, a tragedy made famous in the 1984 film The Killing Fields. The Khmer Rouge, which had been loosely allied to the Vietcong during the war, took the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, in April 1975, three weeks before the fall of Saigon. While the Vietnamese victors were harsh but disciplined, the Khmer Rouge, under the mercurial ideologue Pol Pot, embarked upon a massacre. Cambodia’s population was then 7.5 million, and over the next few years about a quarter of its people were murdered. The first targets were “intellectuals” like schoolteachers and lawyers. When they ran out, Pol Pot targeted anyone not of the Khmer race—Laotians, Thais, and Vietnamese. Then, desperate for more victims, he hunted down the traitors within, Vietnamese “living in Cambodian skins,” a case of a ruler looking for someone else to blame. Khmer troops attacked villages across the border in Vietnam, finally prompting Hanoi to invade. On December 25, 1978, it went in with 150,000 troops, and two weeks later ended the genocide and took Phnom Penh.

Beijing had supported the Khmer Rouge, and less than six weeks after Cambodia fell, China invaded Vietnam on what it called a punitive mission, insisting that, like India seventeen years earlier, Vietnam needed to be taught a lesson. But, this time, China miscalculated.

VIETNAM’S ARMY HAD been at war for generations. Skilled and battle-hardened, fighting was in its DNA. China’s most recent cross-border military action had been in Korea, though that had ended more than twenty-five years earlier, and it had never imagined the ferocity of the resistance. Vietnam took advantage of a network of tunnels, its long experience of guerrilla warfare, and modern American equipment seized in its victory four years earlier in the south. Chinese troops did eventually reach a string of provincial cities, but with heavy casualties and often in hand-to-hand street combat. By March 6, 1979, Beijing had had enough and announced it had achieved its objectives. As Western military analysts swiftly concluded, Vietnam had given China an unexpected and very bloody nose.

This small war also reflected ongoing antagonism between China and the Soviet Union. Beijing was convinced that Vietnam’s move on Cambodia was part of a Soviet plan to control Southeast Asia at China’s expense. In many respects its suspicion was justified. Moscow did pass onto Vietnam satellite and signals intelligence used to attack Chinese positions. Later that year, the Soviet Union signed a twenty-five-year lease on the Cam Ranh Bay naval base, giving Moscow a new strategic Cold War advantage in the Asia-Pacific.

What happened next, after the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War, shows how skewed the global world order can become, resembling some of the arguments surrounding the conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa and the impact on the people in affected areas. Far from being praised for ending the Khmer Rouge genocide, Vietnam was ostracized. Despite the atrocities being well chronicled, the Khmer Rouge kept its seat at the UN and sanctions against Vietnam were ratcheted up. It was as if, after Berlin had fallen in 1945, the Nazis were still recognized as Germany’s legitimate government and allowed by the international community to govern large swaths of the country. Those responsible for the Cambodian massacres walked the corridors of the UN headquarters in New York protected by diplomatic immunity, eating in the finest restaurants, and courted by US politicians playing their next Cold War cards.

One was Republican congressman Stephen Solarz, chair of the Asia-Pacific Affairs Subcommittee. He advocated sending arms to guerilla groups trying to overthrow the Cambodian regime that was now controlled by Vietnam. Solarz tried to argue that no weapons would go to the Khmer Rouge, but there were warnings here of what has evolved in Syria, with the West arming and training guerrilla groups that ultimately merge into one another until it is impossible to tell friend from foe.

In Cambodia, Solarz’s aim was to create a coalition of guerrilla groups that would force out the Vietnamese and their strongman, Hun Sen, a young Khmer Rouge guerrilla fighter who had defected. British prime minister Margaret Thatcher was among the world leaders who joined in this argument. “The first thing we need to do is get the Vietnamese out,” she told a British television show. “Most people agree that Pol Pot could not go back. … There’s quite an agreement about that. Some of the Khmer Rouge are very different. There are two parts of the Khmer Rouge. There are those who supported Pol Pot, and there is a much more reasonable grouping within the Khmer Rouge.” When the interviewer pressed her on this point, Thatcher said, “That is what I am assured by people who know. So, you will find that the more reasonable ones within the Khmer Rouge will have to play some part in the future government.”47

Around that time I visited a village on the border with Cambodia and Vietnam. Neak Leung became famous in 1973 when an American bomber mistakenly dropped its payload there, killing 130 people and injuring some 250. It was a tragedy in the fog of war, but one credited with propelling much Cambodian support toward the anti-American Khmer Rouge insurgency.

Clustered in a bamboo shelter with a dirty straw roof, the villagers recounted how their peace had suddenly been shattered by bombing, the village lit up, craters yawning in the road as in an earthquake. They ferried the injured to a makeshift clinic in wooden carts designed to carry rice sacks. Many in the village had been murdered by the Khmer Rouge. One old woman spoke about them bursting into the house, taking her baby granddaughter, and hurling her up in the air to catch the tiny body by impaling her on a bayonet. This practice was also on display in the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, a former Khmer Rouge prison where many murders took place. As with the Nazis in their concentration camps, the Khmer Rouge kept meticulous records of who was murdered and how.

Both America and the Khmer Rouge had bought unspeakable suffering to Neak Leung while Vietnam had delivered peace. It was far from perfect, but, like Jurrick Oson in Masinloc, the villagers could now get back to their lives. They showed minimal emotion as they told their stories, their eyes expressionless, as if cruelty at this level was part and parcel of their lives. That was, until I asked if they had heard of Congressman Stephen Solarz. They had not. I explained that Solarz was an American politician who wanted to send money and weapons to the Khmer Rouge and other rebel groups. As this was relayed through my interpreter, faces tightened. One woman let out a scream and put her hand to her mouth. Many looked down at the damp ground, shaking their heads.

“Why?” one asked.

“To overthrow the Hun Sen government,” I said.

“Why?” several repeated simultaneously.

I could not explain it. This was a small community. Everyone had lost friends and family to the Khmer Rouge or to the Americans. To them, the suggestion of more weapons and war was incomprehensible, and highly traumatic.

Shortly after that I drove up to the Sino-Vietnamese border, where Chinese tanks had come across in 1979. It was officially closed. There was still cross-border shelling, mostly initiated by the Chinese. That day, however, the border area was a huge market, alive with people—merchants crisscrossing with bicycles, electric fans, motorbikes, cookers, animals, wads of money. It didn’t matter if they were Chinese, Vietnamese, or Martians as long as there was something to buy or sell. Someone had strung up a sound system that played an album by the British band Boney M. Hundreds of busy people peeled off bank notes and swapped goods to the rhythm of “Ra-Ra-Rasputin” and “Rivers of Babylon”—a disconnect between politicians with worldly visions in faraway capitals and how people really wanted to live.

A ONCE GRAND French colonial building with faded yellow walls and peeling wooden shutters flung open to the sunlight is home to Vietnam’s Military History Museum, where at the front entrance stands a captured American Huey helicopter and a crushed armored car, displayed as symbols of victory. The museum itself is a subtle indicator of how Vietnam deals with its enemies.

In the foyer, huge murals depict Vietnamese victories against China in the distant past. One showed huge wooden stakes cunningly driven into the seabed. At high tide, as Chinese warships approached the Vietnamese coastline, the stakes were hidden under water. When the tide receded, the Chinese found their ships trapped as if in a wooden cage and the Vietnamese moved in for the kill. That was in 948. Other pictures showed a battle in 1077 and another in 1427, when ten thousand Ming dynasty troops were slaughtered by the Vietnamese.

But there was no reference to the wars of the twentieth century: losing half the Paracel Islands in 1956 and the other half in 1974; Johnson Reef in 1988; the 1979 border war and the shelling skirmishes that didn’t end until 1987. It was as if Britain’s Imperial War Museum had forgotten about Germany, or the United States had thrown a sheet of amnesia over the Iwo Jima Memorial near the Pentagon. And the displays were very different from those I had seen in the 1980s, when the entrance was then marked by three military armored vehicles, one on top of the other, a French one at the bottom, an American in the middle, and a Chinese one on the top with its red star visible on the side. All that had gone. Now, in the forecourt, there was no mention of China being among Vietnam’s conquests, a small Asian way of saying Vietnam accepted China’s place in the region and would not damage its pride.

The exhibits concentrated on France and America, Western powers much farther away and less relevant in today’s regional context: the planning of the 1968 Chinese New Year/Tet Offensive in the south, the taking of Saigon in April 1975, the intricate tunnels used to shelter people from US bombing.

There were scale models and maps showing the tactics that went into surrounding the French garrison in the hilly terrain of Dien Bien Phu in the northwest of the country, commanded by the legendary Vietnamese general Vo Nguyen Giap. Through his experience in leading the resistance against Japanese occupation, Giap had engineered the defeat of French colonialism in Asia. I met Giap in the early 1990s, in Hanoi; he had just turned eighty. He spread maps of the battle area on a huge chart table and spoke quietly, his expression pensive, as if he were planning the battle again. “I am thinking about what I could have done better,” he said.

Giap had moved heavy guns up through jungle terrain and dug tunnels so they were hidden, overlooking French positions. In a mix of guerrilla and trench-style warfare, Giap brought his troops forward. Casualties were heavy, progress steady, and the antiaircraft guns took their toll on French aircraft trying to supply the troops. The siege that lasted more than two months, and the French surrender in May 1954, forced a change of government in Paris, the declaration of independence for Vietnam, and the withdrawal of France from Indochina.

The French defeat coincided with an international peace conference in Geneva about the future of the Korean Peninsula. Vietnam was tagged onto the end of it, and the United States remained determined to stop communism gaining a hold over the whole country. It was agreed that Vietnam would be divided along the seventeenth parallel, with Hanoi the capital of North Vietnam and Saigon the capital of the South. Elections were to be held after two years, in 1956, but when the time came, the United States instructed South Vietnam to cancel them. President Dwight D. Eisenhower was convinced that Ho Chi Minh would sweep to power and spread his charismatic communism to Thailand, Indonesia, and beyond. That decision led to an insurgency in the south and, in 1959, Vietcong guerrillas killed the first two American military advisers. Fourteen years and fifty-eight thousand American deaths later, the United States was forced out of Saigon.

Here was an earlier example of what unfolded in the early twenty-first century, where democratic elections produced a winner who did not serve Western interests, such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt in 2012, and the pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych in Ukraine in 2010. Each leader was ousted not by elections but by street protests backed by the West.

Vietnam’s instability in 1956 gave China an opportunity to make its first move on the South China Sea. It took the Amphitrite Group, in the eastern section of the Paracels. There was no fighting, but South Vietnam responded by sending troops to the Crescent Group in the western section, which China then seized violently in January 1974. Among the museum exhibits, however, there was no mention of the Paracel Islands. These military defeats are airbrushed from Vietnam’s history.

On central display was a dog-eared and faded telegram sent from Hanoi in early April 1975 to Vietnamese generals in the field instructing them to move “swiftly” and “not to waste a minute” in taking Saigon. They did exactly that. On April 30, Vietnamese tanks drove into the southern capital, and the United States suffered its biggest defeat of the Cold War. Browsing the exhibits with me were American Vietnam veterans, shaking their heads and asking what it had all been all about.

“We called these guys monsters and murderers,” said one named Mike, striking up a conversation. “But they were soldiers, just like I was, conscripted and following orders of the North Vietnamese government. I understand now what was going on in Charlie’s head. But I’ve no idea what’s going on in the heads of these Islamic groups, executing people on camera, blowing up women and children.”

“But did you understand the Vietcong back then?” I asked.

“I didn’t have a fucking clue. They were evil terrorists; that’s all I knew. And now they’re my best fucking friends.”

After the displays on the fall of Saigon, there is nothing on the Cambodian war that followed and which lasted more than ten years from the late 1970s to the troop withdrawal in 1988, nor on the short border war in 1979.

The Vietnamese call their campaign against the French the Colonial War. With the Americans, it was the Necessary War. But in Cambodia and with China, at least within the museum, no modern war has taken place. “We don’t have any exhibits on this,” said a young museum guide, Dinh Thi Phuong. “We don’t want any more wars. But we do keep one room empty just in case.”

Yet confrontation was routine, with a high risk of violence breaking out, not least around the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea where Vietnamese fishing crews were being assaulted by the China Coast Guard and the maritime militia just as the Filipino fisherman, Jurrick Oson, was around Scarborough Shoal.

IN THE OFFICE of the chairman of Vietnam’s Ly Son District, I opened a map of Southeast Asia and asked him to draw on it the Nine-Dash Line. Ly Son comprises three islands in the South China Sea about twenty miles from the Vietnamese mainland and is the home base for most fishermen heading out to the Paracel Islands. Tran Ngoc Nguyen was a neat precise man in his forties, casually dressed in a white and black striped shirt, working in a 1950s-style office. Dark wooden glass-fronted cabinets behind his desk held documents tied together with string. Other papers, secured by black metal clips, were spread out on either side. Tran had lined up his laptop and iPhone neatly next to him. Apart from those, there was no means of communication.

Tran examined the map, cleared more space on his desk, placed his spectacles next to his iPhone, and brought out a red pen. Slowly he traced China’s claim, pausing to think, doing it in a single line and not the dashes that Beijing used, moving upward from the island of Borneo, through the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal, hugging coastlines, across and through the Paracels. Then, hardening the pressure, he drew the line right across Ly Son Island, where we were.

“You mean China is claiming even your island?” I asked.

“Yes. They have no coordinates for this line. No one knows exactly where it is, so for defensive purposes we must assume we are at risk.”

Vietnamese sovereign waters stretch twelve miles off the coastline, and we were twenty miles out. Technically, Vietnam also controlled a twelve-mile radius around us, but all of that was under dispute.

While Scarborough Shoal is a sea-washed reef, Ly Son is a jumping place filled with the strident sounds of a little metropolis, with a spanking new hotel built right on the harbor. The ferry ride across had been chaotic and crowded: huge packages were handed from jetty to boat across the water, people somehow crammed into the cabin and on deck, and on the bow was an arrangement of yellow flowers, a tribute to someone who had drowned—though how, exactly, was not made clear. Deep sea fishing boats were anchored in the small harbor. Children played in the water on floating rubber tires.

Lined up on shore were yellow taxis, one of which took us up to a map museum on windy high ground overlooking the sea that smelled of mustiness and insects. Moths flitted around the ceiling. The main exhibits were historical maps published in America, Britain, France, and pre-Mao China, all showing Chinese territory stopping on the southern tip of Hainan Island with no reference to the Nine-Dash Line.

There were also photographs and maps of Trưởng Sa, the biggest of the twenty-nine islands that Vietnam occupied in the Spratly Islands. Trưởng Sa was 290 miles from the Vietnamese mainland and garrisoned with about two hundred troops. One photograph showed an arrowhead-shaped piece of land with a runway running right through it. Gregory B. Poling’s satellite images at the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative had been tracking how Vietnam was responding to China’s island building with new construction of its own. There was work in progress on ten of the twenty-nine islands, mainly to extend existing jetties and shelters, although minimal compared to what China had been doing. Vietnam had reclaimed 120 acres of land compared to China’s more than three thousand.

Outside this small museum stood a tall statue that paid tribute to Ly Son fishermen who over the centuries had worked around the Paracel and Spratly Islands. “In ancient times, Ly Son fishermen acted as coast guards to rescue those in trouble at sea and to protect our sovereignty,” read a translation of the inscription. “These statues are a monument to them. Now the coast guard safeguards these islands and helps our fishermen fish there in peace.”

Except it’s too big a job for the coast guard. After finishing drawing the Nine-Dash Line, Tran produced a file that listed attacks by China on fishermen from Ly Son. “There are more and more incidents,” he said. “Almost half the boats that go to our traditional fishing grounds now get attacked—at least twenty every year. Of course, we are worried about the Chinese military, their safety, and the damage to their boats. But Vietnamese fishermen do not scare easily.”

The next day, in the early morning darkness, we went out on a Ly Son fishing boat.

The Vietnamese vessel was much sturdier than Jurrick Oson’s Philippine banca with its bamboo outriggers. Even so, there was nothing modern about it. It was cramped and cluttered. A faded Vietnamese flag flew on a mast at the front, and another above the wheelhouse. Inside there was no state-of-the-art marine equipment—just a radio, a compass, and old rusting dials.

“All of us are threatened every time we go out,” said Vo Van Chuc, the sixty-two-year-old owner, as he started up the motor with a belch of black smoke out of the funnel next to the wheelhouse. He had been fishing since he was a child. Only in recent years had he experienced serious danger. With him was Vo Van Giau, (no relative) age forty-two, who in July 2015 was beaten up by China Coast Guard crews using his own fishing equipment as weapons.

As Vo Van Chuc steered us out of the small harbor, the breaking dawn cast a red-orange rim around the horizon and Vo Van Giau told his story. He was skippering a fishing boat, like the one we were on. They were working near the Paracel Islands when a China Coast Guard vessel sped up and rammed into them. The Chinese boarded. They were armed. They dragged Vo Van Giau out of the wheelhouse, kicked him, and made him lie on the deck while they smashed up the wheelhouse. They beat his crew using fishing equipment like hammers and iron rods. Then they took Vo Van Giau across to their vessel. “They forced me to kneel down with my hands on my head. I couldn’t see anything around me. They beat me on my shoulders, my neck, and my back. They kept kicking me in the side.” To illustrate, he pulled a heavy wooden mallet from a bundle of fishing equipment and struck himself softly on his shoulders and against his sides. He continued, his voice breaking at times. “My father fished these waters, my grandfather and my great-grandfather. From ancient times, they have belonged to Vietnam. Now China has claimed them and invaded them illegally.”

He showed photographs of his injuries on his phone—huge swelling bruises and cuts. The attack lasted well over an hour. The Chinese left, telling them not to come back. Vo Van Giau’s boat was so badly damaged that it had to be towed back to Ly Son.

Back on the island, we congregated in skipper Vo Van Chuc’s spotless but sparsely furnished house with his neighbors and generations of their extended families. These were the foot soldiers of Vietnam’s current conflict with China, and there was a feeling of defiance, that they shouldn’t give up. Among us was eighty-one-year-old Phan Din, who still crewed on Vo Van Chuc’s boat. He had lived through all the troubles of Vietnam’s modern history and fully intended to keep working. “We are used to having enemies,” he said jovially. “But we are clever people. I began work under the French colonialists as a driver for their officers. I had to take them to the beach with their mistresses and make sure their wives didn’t find out. That’s how I started being clever. If we think harder, we can beat the Chinese.”

As the conversation played out, two things became clear. First, as in Masinloc, few of the younger generation wanted to follow their parents into the fishing industry. Vo Van Chuc’s thirty-six-year-old son, Phan Thi Hue, began work as a fisherman but had now gone into tourism while his wife ran a shoe shop. Vo Van Giau had a seventeen-year-old son and two daughters, ages thirteen and eight. They used to go on short fishing trips with him. After seeing his injuries, neither has stepped on a boat. The second point was that if they were going to fish around the Paracels they needed their government to protect them, and that wasn’t happening. “Fishing is too hard, with very little money,” explained Vo Van Chuc. “It is also becoming dangerous.”

Vo Van Giau said he planned to keep fishing. “But we want the Chinese to stop attacking us. We need to fish without this threat, and we hope diplomatic negotiations will quickly bring us peace.”

Just over a year later, in a flurry of diplomatic activity, China and Vietnam tried to patch things up. Vietnamese defense minister Ngo Xuan Lich visited Beijing in January 2017, followed a week later by Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc. He stayed six days, an unusually long time, recalling the long-ago era when Vietnamese kings had to journey to China to pay their respects and bring gifts. Vietnam’s economy was too dependent on Chinese trade. Soon, China would be overtaking the United States as Vietnam’s biggest export market. For that to work, Vietnam needed greater access to China’s markets, which would be blocked if it picked a fight over the Paracel Islands and its injured fishermen.

With Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand already under China’s sway, Vietnam was hemmed in. If it opposed China outright, it would lose. If it compromised too much, it risked returning to being a vassal state, and it had fought so many wars to escape that. “In our history, they tried to use military power to make us a province of China,” Tran Cong Truc, former head of the National Border Committee, told me. “Our kings used to travel to Beijing and brought them gifts so we could keep our independence. We may have to do a little of that again.”

On the way to Ly Son, I had stopped by the nearest Vietnamese Coast Guard station at Quang Ngai, where, in a formal meeting room flanked by uniformed officers, the commander Vu Vanh King recited the mission and achievements of his units. “Patrolling Vietnamese territorial waters is the focus of our mission,” he said. “As coast guards we always complete our mission.” He took us down to a small jetty to show us a twenty-five-hundred-ton patrol vessel, built in the Netherlands, and revealed that his biggest problem was budget. To take on China, he needed more and better-equipped vessels.

Although Hanoi and Beijing have what they call a “comprehensive and strategic cooperation” agreement dating back to 2008, Vietnam has little trust in China. Several officials made clear that they do not believe in the long-term future stability in the spirit of “good neighbors, good friends, good comrades and good partners” that the agreement is supposed to secure.

“You do not haul a drilling oil platform into your neighbor’s backyard if you are working toward that,” a senior diplomat told me. “You do not hit your neighbor’s fishermen with mallets and try to sink their boats.”

When I asked for a comment on the attack on Vo Van Giao, the Chinese Foreign Ministry said it would not comment on an individual case, but that it had the right to enforce measures against boats that had illegally entered its waters “China is unswervingly committed to peacefully resolving disputes,” it said.

That commitment has cut little ice with the Vietnamese, who have been reaching out for help. Their defense budget has increased to 8 percent of gross domestic product, or five billion dollars a year—still nothing compared to China’s $150 billion, a 7 percent increase in 2017. Russia supplies by far the bulk of Vietnam’s weaponry, delivering Sukhoi-30 fighter aircraft and Kilo-class diesel electric submarines. But another hand of friendship reaching through the Strait of Malacca to Vietnam has been India, supplying weapons such as the Akash surface-to-air missile system and military training. It has also bought maritime oil exploration leases. One is the twenty-seven-hundred-square-mile Block-128 in the Phu Kanh Basin in the vicinity of Ly Son island. Vietnam angered China in July 2017 by extending the lease for another two years. Because of the diplomatic tension, there is little chance of the site rendering anything of value in the near future. Both Vietnam and India see the venture as being more strategic than commercial, showing an Indian presence in a disputed area of the South China Sea.

India, like Japan, is the bedrock of the US-built coalition aimed at keeping China’s rise within the boundaries of international law. There is, however, a question of how suited India might prove to be for this task. Is it big enough to stand on its own, or, like the smaller Asian countries, does it risk falling into China’s arc and, in Beijing’s eyes, becoming the biggest prize of all in its collection of vassal states?