10. London Exploits

Mrs Blewitt could hardly believe that Ben no longer wanted a dog. In her experience, he did not give ideas up easily; besides, if he were like Paul or Frankie, he needed an animal of some kind. Well, within reason, he could have any small one that wasn’t a dog.

‘How would you like a white mouse, like Frankie’s?’ Mrs Blewitt asked.

‘No, thank you. I don’t want a white mouse.’

‘Well, then –’ Mrs Blewitt swallowed hard; ‘well, then, a white rat?’

‘No, thank you,’ said Ben. ‘I don’t want anything at all. I just want people to leave me alone. Please.’

He really meant what he said: to be left alone, in peace and quiet, so that he could shut his eyes, and see. For, by now, night-time visions were not enough for him. He saw the dog Chiquitito as soon as he closed his eyes in bed, and they were together when he fell asleep, entering his dreams together. But, when he woke in the morning, a whole day stretched before him, busy and almost unbearably dogless.

You might have thought that weekends and half holidays would have provided Ben with his opportunity, but not in a family such as the Blewitts. Ben’s mother did not like his staying indoors if the weather were fine; and, if it were wet, too many other people seemed to stay indoors.

So Ben reflected, as he slipped up to his bedroom one wet Saturday afternoon. He had left his father downstairs watching football on television; May and Dilys were cutting out dress patterns; Mrs Blewitt was advising her daughters and making a batch of buns for tea; Paul had disappeared, and Frankie –

When Ben reached the bedroom, there was Frankie. He was sitting cross-legged and straight-backed on his bed: this meant that he was exercising his white mouse. The mouse ran round and round his body, between his vest and his skin, above the tightened belt. In her ignorance of this Mrs Blewitt always marvelled that Frankie’s vests soiled so quickly – had such a trampled look.

At least there was no Paul in the bedroom, although Paul’s pigeon loitered on the windowsill, peering in.

But Frankie was going to talk. ‘I suppose it’s because you’re older than I am that you can have one … A white rat! And Mother always used to say that the very idea made her feel sick!’ Mrs Blewitt’s offer to Ben had gradually become known. Such a piece of information seeps through a family to any interested members, rather as water seeps through a porous pot.

‘But I don’t want a rat.’ Ben climbed on to his bed and composed himself as if for a nap.

‘If you take the rat,’ said Frankie, ‘I’ll trade for it: some really good marbles –’

‘No,’ said Ben.

‘– and I’ve a shoebox full of bus tickets. And another of milk-bottle tops.’

‘No.’

‘You’re a grabber,’ Frankie said coldly. ‘But, all right, you can have it: my penny flattened on the railway line.’

‘No,’ said Ben. ‘I told you: I’m not having the rat. I don’t want it. I just want to be left alone. I just want peace and quiet to shut my eyes.’

There was a very short silence. Then Frankie said, ‘This is our room just as much as yours, and I can talk in it as much as I like; and you look just silly lying there with your eyes shut.’

‘Go away.’

Frankie went on grumbling about his rights, which distracted Ben. Then he fell abruptly and absolutely silent, which was distracting in a different way. Ben opened his eyes and jerked his head up suddenly. Sure enough, he caught Frankie at it – sticking out his tongue, wriggling his hands behind his ears, all at Ben, in the most insulting manner.

‘I’ve told you to go away, Frankie.’

‘This is our room as well as yours. Some day it’ll be only ours, and then you won’t be allowed to come in at all without our permission.’ This was a reference to the re-allotting of bedrooms that would follow May’s marriage and Dilys’s leaving home with her. The girls’ bedroom would be left empty. Ben, as the eldest of the remaining children, was to move into it, by himself. He looked forward to the time: then at least he would be allowed to shut his eyes when he wanted.

‘And until then we just kindly let you share this room with us,’ said Frankie.

‘Go away, I say!’

‘A third part of it, exactly – to look silly in, with your eyes shut!’

Frankie was goading Ben; Ben was becoming enraged. It was all more unbearable than Frankie knew. Ben was not allowed even a dog so small that you could only see it with your eyes shut, because he was not allowed to shut his eyes.

At least he was bigger and stronger than Frankie. He became tyrannical. ‘Get off that bed and go away – now!’

Frankie said, ‘You’re just a big bully.’ But he was smaller and weaker, and he had the responsibility of the white mouse. He got off the bed – carefully, because of the mouse – and went away.

Ben felt only depressed by his unpleasant triumph. He was at last alone, however. He shut his eyes: the dog Chiquitito sat at the end of the bed …

Suddenly Ben was sure in his bones that he was still being watched. He opened his eyes a slit. There seemed no one. The pigeon was staring through the glass – but not at him. Ben opened his eyes altogether to follow the direction of the bird’s gaze: below Paul’s bed lay Paul. He had been going through his stamp album, but now he was watching Ben with curiosity.

‘Spying on me!’ Ben shouted with violence.

Paul rolled out of reach of his clawing hand, and said: ‘I wasn’t! There was nothing to spy on, anyway. You were just lying there with your eyes shut and a funny look on your face.’ But he scrambled out of reach of Ben’s fury, and fled. Ben locked the bedroom door after him, although he knew that he had not the least right to do such a thing. He shooed the pigeon off the windowsill. Then, with a sigh, he composed himself upon the bed once more to shut his eyes and see the dog Chiquitito in real peace …

Almost at once Paul came back, having fetched Frankie. They rattled the doorknob and then chanted alternating strophes of abuse through the keyhole. Frankie ended by shouting, ‘You’re not fit to have a white mouse, let alone a white rat!’ Their father came upstairs to see what the noise was, and made Ben unlock the door. Then his mother called them all for tea. That was that.

So, as Ben was clearly never going to see enough of his dog in the privacy of his own home, he began to seek its companionship outside. He discovered the true privacy of being in a crowd of strangers.

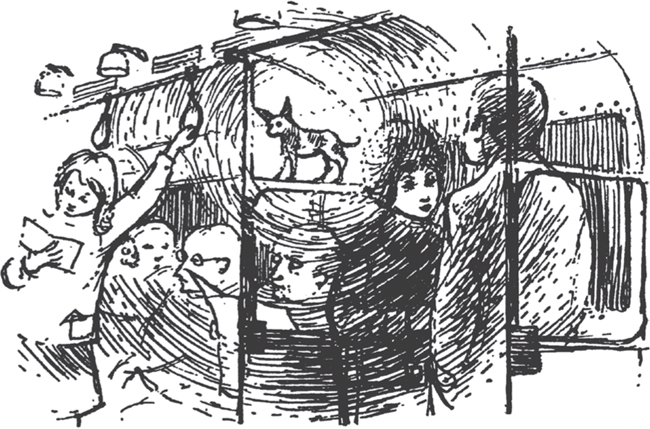

In a Tube train, for instance, Ben could sit with his eyes shut for the whole journey, and if anyone noticed, no one commented. He felt especially safe if he could allow himself to be caught by the rush-hour, and on the Inner Circle Tube. The other passengers, sitting or strap-hanging or simply wedged upright by the pressure of the crowd, endured their journey with their eyes shut – you see them so, travelling home at the end of any working day in London. Like them, Ben kept his eyes shut, but he was not tired. And when the others got out at their various stations, he stayed on, going round and round on the Inner Circle – it was fortunate that Mr Blewitt never knew of it – and always with his eyes shut. No one ever saw what he was seeing: a fawn-coloured dog of incredible minuteness.

If Ben were sitting, he saw the dog on his knee. If he stood, he looked down with his shut eyes and saw it at his feet. The dog was always with him, only dashing ahead or lingering behind in order to play tricks of agility and daring. When Ben finally left the Tube train, for instance, the Chihuahua would play that dangerous game of being last through the closing doors. While Ben rode up the Up escalator with his eyes shut, the Chihuahua chose to run up the Down one, and always arrived at the top first. Only a Chihuahua called Chiquitito could have achieved that – and in defiance of the regulation that wisely says that dogs must be carried on escalators. This dog exulted before its master in deeds which would have been foolhardy – in the end, disastrous – for any other creature. On all these occasions the dog’s coat was black, as it had been for the encounter with the thousand wolves.

On buses, the Chihuahua sprang on or off when the vehicle was moving, as a matter of course. (Ben trembled, even while he marvelled.) But its greatest pleasure was when Ben secured the front seat on the top deck, and they went swaying over London together. Ben had always loved that; and all the things that Ben liked doing in London, the dog Chiquitito liked too.

Ben would walk to the bridge over the River, rest his elbows on the parapet, and shut his eyes. There was the dog Chiquitito poised on the parapet beside him. The parapet was far enough above the water to have alarmed a dog such as Tilly, but not this much smaller dog. Without hesitation, it would launch itself into the void, and, in falling, its tininess became even tinier, until it reached the water, submerged, and came up again, to sport in the water round unseeing crews and passengers on river-craft.

Then Ben whistled softly and briefly. At once the swimmer turned to the bank with arrow-swiftness, reached a jetty, leapt up the steps, ran under a locked gate (any other dog would have had at least to squeeze through), and disappeared from view. A moment later the dog trotted back on to the bridge, to where Ben waited.

Once Ben used to wonder what a Mexican Chihuahua thought of the greasy, filthy London Thames after the wild, free rivers of its native country. But nothing of the smell, dirt, noise, traffic and other roaring dangers of London daunted the Chihuahua. It seemed to take London for granted. It never even cocked an ear when Big Ben boomed the hour.

One day Ben noticed a small silver plate on the dog’s collar: an address plate. Here he read the name of the dog and the name of its home city, as on the back of the lost picture. But the name of the home city had changed:

CHIQUITITO

LONDON