16. A View from a Hill-top

He was Ben’s, then; and not Ben’s.

He was not an extraordinary puppy as yet, and he was much darker than the true Chiquitito-fawn. Nevertheless, Ben hung over him, loving him, learning him, murmuring the name that should have been his: ‘Chiquitito …’

Ben was there when Chiquitito-Brown barked for the first time. Standing four-square and alone, the puppy’s body suffered a spasm of muscular contraction which released itself when he opened his jaws. The open mouth was just about the size to take the bulk of, say a finger-end. From this aperture issued – small, faint, but unmistakable – a bark. Then Chiquitito-Brown closed his mouth and looked round, quivering back in alarm at the sound he had heard.

For the puppy, more like his mother than his heroic namesake, was not brave. That would have to come later, Ben reassured himself; and in the meantime – ‘You’re really Chiquitito,’ Ben told him again and again, trying to teach him his new name and the new nature that went with it. At least the puppy was still very, very small.

Grandpa, of course, did not know of the renaming; but he guessed, from Ben’s favouritism, which would have been the boy’s choice among all the puppies. On the last day of Ben’s visit, he asked: ‘And what shall I do with Brown, since you can’t take him back to London with you?’

‘What will you do with the others?’

‘Offer them round to the family – your uncles and aunties,’ Grandpa said. ‘And those pups that aren’t taken that way – we shall sell ’em off if we can, give ’em away if we can’t.’

‘Then you’ll have to do the same with him.’ Ben held Chiquitito-Brown squirming between his hands for the last time. He put his face against the puppy’s head, breathed his goodbye.

And, on the evening after Ben’s departure, Grandpa squared up to the table and wrote round to the families offering a gift of a puppy to each. He did not bother to ask the family so far away in Canada, of course, nor the Blewitts themselves.

After some time he began to get the replies. Ben, at home again in London, heard that an uncle who had settled in the Fens, the other side of Castleford, would take one puppy – Midnight; and another – Gravy – was going to the aunt who had married a man in Essex.

Ben laid down the letter which had brought this news, and thought: two puppies gone – that left seven to be disposed of, Chiquitito-Brown being one.

Ben, quite well again now, was back at school, thus altogether resuming normal life. He was never seen with his eyes shut in the daytime; he was never found in strange abstractions of thought. He was a perfectly ordinary boy again – only, perhaps, a little dispirited. But his mother was satisfied that the change to North London would work wonders in Ben, and in them all. For the Blewitt family were going to move house: Mrs Blewitt’s idea had really been a plan, as her husband had grasped, and now it had been decided upon and would be carried out.

‘But I’ve to be within reach of my job, mind that,’ said Mr Blewitt. Mrs Blewitt pointed out that, for someone with Mr Blewitt’s kind of Underground job, there wasn’t much to choose between living towards the southern end of the Northern Line, as they did at present, and living towards the northern end of the same Line, as they would be doing.

‘Yes,’ said Mr Blewitt. Then he closed his eyes: ‘But the upheaval – leaving somewhere where we were settled in so well.’ Mrs Blewitt pointed out that the departure of May and Dilys had already unsettled them: the house had become too big for them. (Perhaps, if the Blewitts had not been so used to squeezing seven in, five would not have seemed too few in the space. Or perhaps they would not have seemed too few if Mrs Blewitt had not been thinking of the comfort of living nearer to her daughters.)

‘And besides,’ Mrs Blewitt went on, ‘the air –’

‘I’ve heard enough about the flavour of that air,’ her husband said with finality. ‘If we go, we go. That’s all there is to it, Lil.’

‘We go,’ Mrs Blewitt said happily, as though all problems were settled now. So the rest of the family were told. Frankie – who took after his mother, everyone said – was delighted at the thought of the excitement of removal. Paul only worried about his pigeon: he did not yet realize that birds can be as cordial in North London as in South. Ben said nothing, thought nothing, felt nothing – didn’t care.

His keenest interest, but sombre, was in the news that Grandpa sent in his letter-postscripts. Old Mr Fitch was now getting rid of the rest of Tilly’s puppies, one by one, in the Little Barley neighbourhood. Jem Perfect of Little Barley was taking one – Punch; and Constable Platt another – Judy. That left five, Chiquitito-Brown among them.

‘It’s only a question of time,’ said Mrs Blewitt. ‘If anyone can hear of the right kind of house or flat for us, it will be Charlie Forrester. He’s on the spot; he’s in the know. We only have to be patient.’ She glowed with hope.

Another weekly letter came from the Fitches. ‘Here you are, Ben,’ said Mrs Blewitt, ‘there’s a message for you again.’

The postscript read:

TELL B MRS P TOKE TILDA

That meant that the Perkinses from next door had taken the puppy called Tilda. It would be nice for Young Tilly to have her own daughter living next door. And that left four puppies, Chiquitito-Brown still among them. Ben suddenly realized that his grandfather must be keeping his – Ben’s – puppy to the end: he intended to give him away the last of all. But, in the end, he would have to give him.

The Blewitts were going to look at a family-sized flat that Charlie Forrester had found for them in North London. It was a house-conversion job, he said, and wouldn’t be ready for some time; but it might suit them. There was even a back-garden, or yard, nearly fifteen foot square. As the only viewing day was Sunday, all the family went.

There seemed nothing special about the district – just streets leading into streets leading into streets – or about the house itself – just like all the other houses in all the other streets: Ben himself could not even dislike the street or the house, outside or in.

His mother was disappointed at it. ‘Only two medium-sized bedrooms, and a little box of a room where Ben would sleep.’

‘I thought his present bedroom was too big,’ said Mr Blewitt.

‘But this is poky.’

‘It would just take Ben’s bed and leave him room to get into it, anyway,’ said May, who had come with her Charlie. She was taking them all back to their flat for tea afterwards.

‘Well, what do you think, Ben?’ Mrs Blewitt asked.

‘I don’t mind,’ said Ben. He was indifferent; and Paul and Frankie were bored – they were scuffling in empty rooms, irritating their father, whose nerves were on edge. He sent all three out of the house.

They wandered together from one street to the next and so came to a road that was less of a side street than the others. The two younger boys pricked their ears at the whirring and rattling sound of roller-skates, and took that direction. Ben did not care for the sport, but he followed the others – as the eldest, he was always supposed to be partly in charge.

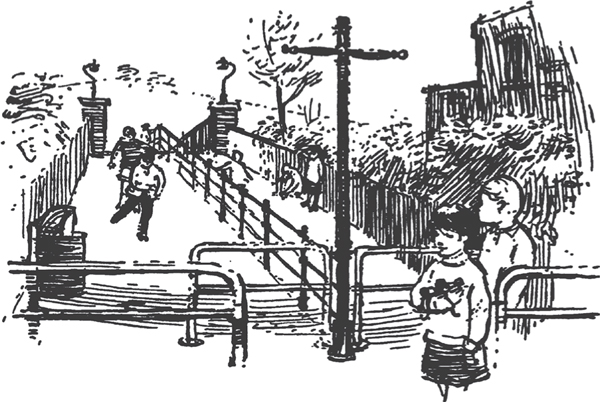

Boys and even a few girls were roller-skating in zigzags down a wide, asphalted footway that sloped to the road, with a system of protective barriers across at that end. Paul and Frankie recognized this as ideal skating ground, fast but safe. They settled down to watch. Soon, Ben knew, they would try to borrow someone’s skates for a turn, and they might succeed. Anyway, they would be occupied for some time.

Ben went on, chiefly because he did not care for all the company and noise. He climbed the sloping way, crossed a railway bridge, and came out by a low brick building. It was probably a sports pavilion, for it looked out over a grassed space, part of which was a football ground. To one side there was a children’s playground with a paddling pool and easy swings. Asphalted paths skirted the whole open space, which sloped steadily still upwards to a skyline with trees.

Ben left the asphalt and struck directly up over the grass towards the highest point in sight. As he climbed he became aware of how high he must be getting. He took the last few yards of the ascent walking backwards to see the view in the direction from which he had come – southwards, right over London.

He thought that he had never seen a further, wider view of London; and, indeed, there is hardly a better one. The extremity of the distance was misted over, but Ben could quite easily distinguish the towers of Westminster and even Big Ben itself. The buildings of London advanced from a misty horizon right to the edge of the grassy space he had just traversed. The houses stopped only at the railway-line. He could see the bridge he had crossed; and now he saw a spot of scarlet moving over it. That would be Frankie in his red jersey, and the spot of blue following him would be Paul. He could see them hesitate, questingly, and then the red and blue moved swiftly in a bee-line to the children’s playground. Well, that would certainly keep them busy and safe until May’s teatime.

Ben had reached his summit facing backwards – southwards – and he had looked only at that view. Now he turned to see the view in the opposite direction.

There were buildings, yes, some way to the right and to the left, for this was still within the sprawl of London; but, between, there were more trees, more grass – a winding expanse.

Ben stared, immobile, silent. People strolled by him, people sat on benches near him, no one appeared aware of the importance to Ben Blewitt of what he now saw. Even if the place were no bigger than it seemed on this first entry, it was already big enough for his purposes. And it went on. He had a premonition – a conviction – of great green spaces opening before him, inviting him. He felt it in his bones – the bones of his legs that now, almost as in a dream, began to carry him forward into the view. Asphalted paths, sports pavilions, and all the rest were left behind as he left the high slopes of Parliament Hill for the wilder, hillocky expanses of Hampstead Heath.