CHAPTER SEVEN

SCOPES

AND BUIS

The ADCO Solo offers multiple reticles, brightness settings, and is easy to mount. Yes, it looks fragile, but my test crew hasn’t broken it yet. If they can’t, few can.

Underneath the rear housing is the reticle selector. On top, the knob controls intensity.

The big advantage a rifle has over handguns and shotguns is accuracy – sufficient accuracy that extended range use becomes viable. Where a 200-yard shot with a handgun (for most handguns and shooters) becomes a “lottery shot” (your odds are about the same), for someone with even a little instruction and practice with a rifle, 200 yards is no big deal.

Magnifying optics allow for more precision in aiming at distance, but at a cost. The optics cost money, they are more fragile than the rifle, and once you start looking through a scope you tend to exclude things not seen through the scope. Non-magnifying optics do not have the advantage of increased magnification aiming ability. They are less fragile than magnifying optics. Some are downright durable. And you are less likely to fall into tunnel vision, as the non-magnifying scopes are simply a “dot in front of the world” view. But even non-magnifying (also known as “red-dot” scopes) can break. For that, you need iron sights. Since the easiest way of mounting a scope is to use a flat-top upper, and such uppers have, by definition, no iron sights, you need a bolt-on sight. Known as Back Up Iron Sights or BUIS, you can have any of a host of them to put on your rifle. The available sights are limited pretty much just by the makers’ imaginations and ability to fabricate a product. They are usually quite durable. After all, they are expected to be there after the optics have been lost, busted or otherwise rendered unusable.

We’ve been putting scopes on ARs for a long time. Almost from the beginning, in fact. In the early years of the AR-15 and M-16, Colt even offered (they didn’t make it, despite what some “experts” have told me) a 3X scope that you could clamp right into the carry handle. Later, that scope was copied by an endless series of Chinese optics companies, some even with faux Colt logos on them. As collectors pieces they compliment a Vietnam-era rifle or build. As optics, they’re better than irons, but not much. The Colt had a built-in trajectory cam. By turning the dial to the target range you’d have the holdover adjusted. Quite a trick for 1967, but the whole package is pretty much a curiosity now.

The ARMS #40 sight is solid, dependable, beautifully machined and very desirable.

A proper BUIS either locks upright, or is spring-loaded.That way, your sights can’t be knocked askew without your knowing it.

The original ARs weren’t all that cool for mounting a scope. The carry handle provided a convenient location. Well, convenient as far as “having a place to clamp” is concerned. It isn’t so convenient when you try to aim. The line of sight of any scope so-mounted is so high over the stock that you can’t really maintain a check weld. It’s more like a “chin weld.” Still, we got by. Some of us went so far as to butcher perfectly-good ARs. We’d lop off the carry handle and drill, tap and screw on a Weaver scope base. The accomplished among us used a milling machine and actually got the top level and the holes in a line. Some I’ve seen looked as if they were done with a hacksaw and belt sander. If you have a so-modified upper, and are having a heck of a (or even impossible) time getting your BUIS zeroed, there’s a simple reason: it is too high.

Fast-forward from the Vietnam War to the 1990s. The need for a flat-top upper is apparent. But what dimensions? Bartocci, in his The Black Rifle II, gives you the blow-by-blow rundown of who, when, where, and who else tried to take the credit. For our discussion here, the fact you need to know is this: the current flat-top top deck height is lower than we fabricated back then by installing a Weaver mount. The “typical” (every gunsmith had his own way of doing it) handle cut-off lowered the top deck of the upper to about 1.80". Add on the thinnest Weaver base and you’re left with a top deck height of 1.900" or more. Over the usual M4/flat-top measurement of 1.83"-1.84" by enough to cause problems. Could the upper have been shaved down some more? Sure, but the lower you go the thinner the wall, and fewer threads are available to clamp the base to the upper. So, most of the old flat-top jobs are unsuited for a modern BUIS install. You can still put a scope on them, but you can’t install back-up iron sights unless they are custom-made for that particular rifle.

As recently as just before the Iraq war, an AR with a scope, or red-dot sight on it, was viewed by many as a “competition gun,” something real men wouldn’t take into a real war. This despite the fact that the government had been buying truckloads of optics, magnifying and red-dot, for some years. Due to the wonders of digital photography the Iraq war has more images, more available for inspection, than any previous conflict. Anyone with a fast internet hookup can search out and closely inspect hundreds or thousands of photos. Having done just that, I can make a bet I heard a long time ago, with a twist: The bet was simple: you paid a dollar for every police officer without a mustache, if the other guy paid you a nickel for every one with a moustache. Only here, it would be pay a dollar for every M-16 or M4 you see with only iron sights, and collect a nickel for every one with a scope of some kind. You might not get rich, but you won’t lose money.

I have seen more than one rifle in Iraq photos that would have been a pretty well-equipped Open class gun in IPSC competition.

Optics

Optics choices for the AR are pretty simple; after all, you’re just picking a scope for a rifle. You’d use the same criteria you’d use for any other rifle: expected ranges, anticipated target size, amount of light available, and durability desired. Of course in the defensive, law-enforcement or military context, durability becomes much more important than in hunting. If I’m spending an afternoon on a ridgeline over a prairie dog town and my scope breaks, I can get another out of the truck. (Rifle or scope, my choice.) Or come back another day. If the bad guys are shooting at me and my scope breaks, I might not have the option of going back to the truck. As for the option of coming back another day – well, things don’t work that way.

Yankeee Hill Machine so far makes the only BUIS that can be folded with the small aperture ready to go.

Scopes selected for military use tend to be heavier, bulkier and a lot more costly than what would be “good enough” for hunting. That’s why you see bullet-proof rings like LaRue and Badger Ordnance on military rifles, and honkin’ big scopes like Leupold or the European makers. A few ounces, or even a pound, of extra weight don’t matter in those circumstances. Consider the situation of a squad designated marksman (or even a school-trained sniper) in a small group of SpecOps troopers, hiding on a ridgeline. Between the bunch of them, the government has spent a staggering amount of money: they all draw pay (not enough, in my opinion) and have since they enlisted. They’ve been fed, housed, clothed, and sent to an impressive number of schools. They’ve been through training exercises that cost bundles of money. Then, the government ships them and all their gear halfway around the world. Going over on a C-5A or a C-17 costs a lot more per-person than flying coach on a commercial airliner. Then, they took a helicopter ride. That chopper requires another group of people; pilots, maintenance techs, air traffic controllers, all of whom cost the government a lot of money. Lying there in the dust, each one of those SpecOps troopers represents a million dollars or more of invested money. Do you really think, once you start considering the costs, that the government really cares that another scope is “just as good” and costs “hundreds less”? If the troopers miss because the scope croaks, then the government may have to marshal millions more in air-delivered ordnance, artillery or drones. My only surprise is that there isn’t a “ball peen hammer” mil-spec test.

You, however, do not have that luxury. You may well find that a less-expensive scope (optic or red-dot) serves your needs just fine, and at much lesser cost. Lesser cost is good, if the savings are spent on practice ammo. Buy as good a scope as you can afford, but always buy enough ammo to be in practice.

Optics and Choices

When I worked in radio, I quickly found out that not just DJs had impressive record collections. Everyone at any radio station who wanted records could collect them. At one radio station, the record representatives showed up on Tuesdays. The playlist committee met on Wednesday, and on Thursday morning, Tanya’s office was opened. When you could go in depended on your place in the pecking order. Typically, there was at least one full stack of records, as tall as my shoulder. What were those records played on? Now there is where they interesting part comes in. DJs typically fell into one of two extremes: they either had a sound system to rival that of the station, or they had a phonographic “system” one step above a child’s Close ‘n Play. Why? Good systems cost money. What the station could afford was the best. It took a lot of money to match that sound quality. A lot of DJs didn’t care, they were “hearing” what they remembered anyway, so a simple, discount system from the local chain store was good enough.

The Armalite BUIS looks a lot like the FG-42 rear sight.

The Armalite hooded folding front BUIS.

The LMT BUIS looks like it is simply a carry handle chopped off. There’s more to it than that, but you wouldn’t be far off.

The M4 carry handle is a BUIS. You just have to carry it and bolt it on when you need it.

And so it is with optics. You can spend for the best, and nothing less. Or you can get optics that are good enough, and put the rest of your money into practice ammo. The Marine Corps (one of those groups sending people to exotic places) has decided the Schmidt & Bender scopes are all that will do. Even with the volume discount, they are spending a lot on glass. If you’re prepared to spend that much, you’ll get optics that will knock your socks off. But so will the price.

Leupold

Leupold & Stevens makes first-class optics, and if you’re serious about shooting then they should be the scopes you use. Yes, there are better optics, but you’ll pay, and pay dearly, for better optics. I covered them in Volume 1, so I need not review them again. I did, however, hang on to them to use them in this book too. That’s how good Leupold scopes are.

Famous Maker

For those not needing (or needing yet) optics in the “make your wallet bleed” category, Famous Maker offers entirely serviceable optics. Well, some are. While I would get Leupold optics sight unseen, you should look through lesser optics before buying. Famous Maker sent me two scopes. One, a compact 2-6X that looked perfect for the AR, proved not to be. The eye relief is so short that I was hard-pressed to mount it far enough back to be able to see through it. And the center portion of the scope was the only part usable. Outside of the center, the field of view had noticeable distortion. Until they make a “MkII” of this scope, pass on it. And I had high hopes for it, too. However, the 2.5-10X Tactical scope is different. Bright, clear and with a mil-dot reticle, it proved quite up to the task of shooting small groups from the bench. Upon arrival I slapped it on the S&W M&P-15, and proceeded to bang a dead-center group sub-MOA with Wolf Performance ammo. The Wolf ammo is an M-193 equivalent, and I have not had it fail to work properly in any of over a dozen rifles. The S&W loves it. The Famous Maker 2.5-10 suffers from the same fault that a lot of “not the most expensive” optics suffer from: narrow eye relief. Any scope you get that isn’t Leupold quality (and thus price) or greater will suffer from narrow eye relief. The scope is a one-inch tube with a 44mm objective. You can get the basic scope for about a hundred dollars, or you can get the illuminated reticle one for two hundred. As an entirely serviceable practice/learning scope, before you spring for your $1200 scope, consider the FM 2.5-10X. It has a lot going for it.

The ADCO Tactical meets the SEP and is judged “good” – as in “Get this one and then spend your money on practice ammo.”

The OSTI night vision scopes can be removed from one rifle and bolted to another, without losing zero. It simply intensifies what’s there and doesn’t provide any aiming of its own.

OSTI

Optical Systems Technology, Inc., makes perhaps the coolest thing a poor, underpaid gun writer gets to play with: an AN/PVS-22 night vision scope. For those of you who have not updated your knowledge since reading of the “starlight” scopes of the Vietnam War, hold on. We’ve 35 years of updating to do in a couple of paragraphs. A night vision scope is basically a television camera. Inside it is an extra electronic array known as a “photomultiplier.” The p-m is an amplifier. When it gets “hit” by a photon on the front (actually, it takes more than one, and the sensitivity of an NVG device is dependant on the threshold of light it reacts to) it responds by squirting ten, a hundred, a thousand out the back. The smaller the photo-sensitive locations on the p-m, the greater the resolution. The greater the amplification, the more it sees. However, you can’t get something for nothing, Early NVGs suffered from “bloom” which is an over-amping of the p-m, causing the whole screen to wash out or have haloes around light sources. Early screens also suffered from “burn-in” in the same way early computer screens did.

Having a high-resolution NVG suite simply means you own the night. Our military owns the night. NVG are also sensitive to infra-red light. So the I-R lasers on every other rifle, vehicle and lamp-post allow our NVG-equipped soldiers, Marines and airmen to see even in total darkness. (Of course, someone else with NVG can see the “flashlight” effect of the IR laser, too.

We are not alone in making NVG. However, we are the best. When the first Russian NVG scopes appeared on the market, they were simply awful. I mounted one for a customer and attempted to bore-scope it. All I got for my efforts was a splitting headache. Trying to discern objects in the dark, grainy, out-of-focus screen was enough to make you crazy. Some users even joke about needing lead shorts to stop the radiation rumored to be coming from them. Newer ones are much better, but still not as good as American NVG. Of course, better costs more, and the best are in use overseas.

What OSTI sent me was their Universal Night Sight, which mounts in front of regular optics. As the AN/PVS-22 is a television camera, you can’t look “through” it when it isn’t on. NVGs don’t work in the daytime. (The military has special day/night scopes but they make regular NVG scopes look inexpensive.) So, the OSTI has a quick-removal mount that lets you attach it directly to a rail in front of a scope. Since the UNS simply transmits an image back, and your regular scope hasn’t been moved, you don’t change your zero. You simply attach and turn on the UNS.

The new Holosights have a better water seal and thus better water resistance.

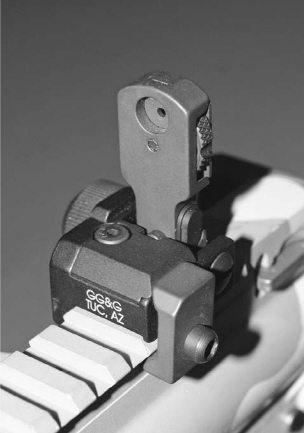

The GG&G A2 (here behind a Holosight) offers two apertures and windage adjustments.

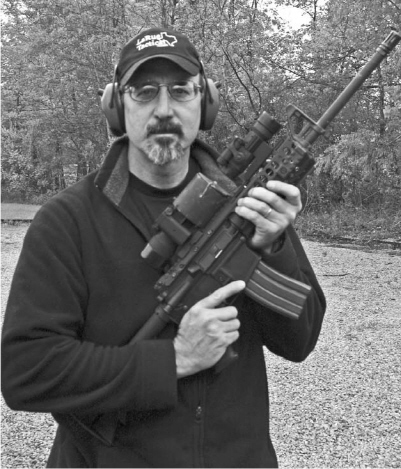

If you plan to mount optics to your AR, and have them stay and survive, you need a tough mounting system. You’re hard-put to get tougher than LaRue.

When I showed it to a friend of mine who is a Chief of Police, he and several other departments were in the process of looking at NVGs for disaster preparedness. He took one look through the OSTI UNS and remarked, “This is worth the price of admission.” And it is. The view is clear enough to read license plates across a parking lot. On a hazily-overcast night out at a military base, I was able to see the stars through the cloud cover, and identify the constellations.

I had a great deal of fun with the UNS OSTI sent me. I first mounted it on my “Police Sniper” 6.8 Remington SPC rifle, and it is a hoot to use. Given even a slight amount of light from someplace (the stars will do, even a sliver of moon is enough to make the world light up) I had no problems whacking gongs or dropping the computer pop-ups on the NG base. What I found was that the OSTI AN/PVS-22 turns on first at the highest gain, and the best setting for me (and many others) was with the gain turned down. Way down. Too much gain interfered with resolution and was tiring to look at for any length of time. I’m sure turning down the gain increases battery life as well as increasing “eye endurance.” However, I have yet to use up the two AA batteries I put in to start this “research” so battery life is obviously not a problem. And you can find AA batteries at any location on earth. If there is a store with batteries, they have AAs.

It is important that you be able to co-witness your irons and your red-dot reticle.

The Meprolight Mepro-21 is a solid and quick-to-use red-dot with a triangle as an aiming reticle.

The Zeiss red-dot is a compact, bright and great little scope.You just can’t co-witness your irons through it.

Once I’d played with it for a while on the 6.8 Police Sniper I then mounted it on the 5.56 DMR. Since the UNS simply transmits its image back to the scope, you can swap it from rifle to rifle without a change in zero. The UNS was even more fun on the DMR. If you had a DMR, a UNS and IR-trace 5.56 ammo, you could indicate a position for someone else with NVG. Thinking about that in a military context (and IR lasers) gets downright scary. Scary for the other side, that is.

The downside? Cost. You’re going to be spending thousands of dollars at the very least. Six or eight, probably. If you buy more, the unit cost comes down, but you’ll have a heck of a time finding five or six friends who also want night vision gear. Of course, for many of us, that isn’t that much for something this fun. And from someone doing predator control, the expenditure is recouped pretty quickly in prevention of cattle losses. If you want something smaller OSTI makes the TaNS, the Tactical Night Sight, which is petite compared to the bigger optics.

You want night-time fun, look into the OSTI UNS. Lest you think they are just re-badged Russian optics, the UNS has a National Stock Number, and is listed with the Defense Logistics Agency.

Man, I hated sending it back. But what’s a poor, under-paid gun writer to do? (Besides take lots and lots of photos?)

The Troy front.

Insights

Insights makes lights and lasers and is in the process of making an optical system. The IOSS is a red dot sight with integrated laser. At the moment of this paragraph it is still in R&D, and the original models appear to be LE or military use only. But give them time, and there will be one for the rest of us.

Optics Bases

The ways to mount magnifying optics to an AR are legion. Well, there are a lot. At the low end, you could do something as simple as fit a Weaver ring set to your M4 upper rail. Or bolt a Weaver adapter into the carry handle of your A1 or A2. While the purists might look down on you (and the second method does have drawbacks) it gets the job done. The more durable, convenient and modern method is a throw-lever mount like the LaRue. Another approach is the GG&G lever, which clamps their bases or mounts to the top of your flat-top AR with a single swing of a large lever. At the top end, Badger Ordnance makes rings that are tougher than your rifle. If you were to mount a scope to your AR with Badger Ordnance rings, and then beat the snot out of the rifle and scope with a hammer, the rings would survive even after the scope and rifle were scrap. A real-world example would be an AR sniper rifle being ejected out of a police car during a collision. The result was a scrapped rifle and scope. But not the Badger Ordnance rings, which survived. Most things that go onto your AR need mounts, but some don’t.

The OSTI night vision scope, mounted ahead of a Leupold 3.5-10X sniper scope. Own this, own the night.

You can’t look through the AN/PVS-22 unless it is on. (Don’t turn it on in daylight.) But you don’t lose your zero taking it on and off.

Red-dot Mounts

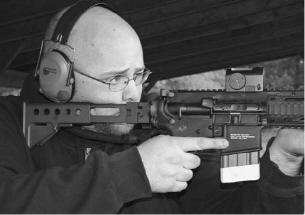

Many red-dot mounts are simply built into the scope body. Others require a base and ring system. There are advantages and disadvantages to both. What you’ll often see with the separate optics and mount system is that the mount is cantilevered forward. Also known as a gooseneck mount, the angle is there to increase usable real estate on the top rail of the rifle. Unless there is a rail system on the handguard (and mounting scopes there can be chancy) you have to mount the scope on the rail. You also need room for the BUIS. And in military use you often need a night vision gear or optic, too. By angling the red-dot optic forward you make room for the NVG. Since the red-dot has no need for eye relief, it can be anywhere. You could mount it at the muzzle if you wished, provided it stayed aligned with the bore. The ideal mounting of the red-dot optic would put it in line with the iron sights so you would not have to change your cheekweld for one or the other.

One advantage to non-magnifying optics is the ability to “co-witness” sights. Simply put, you zero your irons and you zero your optics. Then you turn on your optics and aim through your iron sights. Note the relationship between the dot and your irons. They should agree as to the point of aim/point of impact. Once done, you can check your sights at any time. Let’s say your rifle takes a tumble. If you think your optic or irons took the hit, turn on the optics and aim through your irons. (In a safe direction, please!) If your sights no longer agree as to point of aim/point of impact, then something is amiss. If you know which took the impact, then that’s likely the one damaged. If you don’t, at least you know one of them is wrong, and can set about finding and correcting.

Red-Dot Scopes

The beginning of red-dot scopes in practical competition began with Jerry Barnhart in 1990. He mounted an Aimpoint on a .38 Super Open gun and proceeded to win the Nationals with it. Later that year, Doug Koenig, having mounted a red-dot scope on his Open gun, won the World Shoot. After that, there was no going back. Well, at least not for a few years. The original scopes were dim, had narrow tubes and were quite fragile. It was not unheard of for a competitor to have two or three pre-zeroed scopes in their gear bag. Should one decide to break, they’d unbolt the old one and install the new one. I recall one time, at a USPSA Nationals, after a hard rain the sun came out. My extensively-modified and unsealed scope fogged up. By holding a butane lighter flame against it, I was able to dry it out. We’ve come a long way since then, and Aimpoint has done a lot to advance the field.

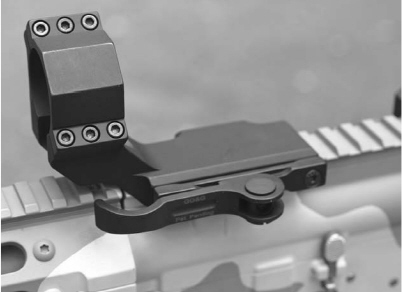

Scopes are no good if they lose zero. And they are much more useful if they can be quickly removed. LaRue answers both needs.

The Matech BUIS is a real-deal DoD sight.It’s compact and offers ranging settings.

No, this isn’t a combo you’d see in Iraq. But with an accurate rifle and a solid mount, a cheap scope serves until you’re practiced or can afford the better optics. Don’t be a slave to fashion.

The method of operation of any red-dot scope is the same: you look through it, at the target. For fast, close-in shooting, you simply let the dot “float” in your field of view. Where it is, is where you hit. Optical purists quibble about which red-dots are and are not perfectly parallax-free. Parallax is the change in point of impact from the dot (or crosshairs) of a scope, when you move the dot or crosshairs from the optical center of the scope by moving your head. A scope with parallax will have the point of impact away from the dot or crosshairs when they are near the edge of the field of view.

In a magnifying optic, parallax can be a problem. Optically, the magnifying scope can be adjusted so it is parallax-free at a single distance. However, the effect is so small at distance that scopes can be said to be “parallax-free” at or beyond a certain distance when properly adjusted. Target competitors fuss over it greatly. A scope adjusted to be parallax-free at fifty yards will show parallax at 100, and vice-versa. When a change of fractions of an inch can mean lost points and lost matches, target shooters get fussy. The lack of magnification and the large dot size means that even a red-dot optic that is not well-engineered and has parallax hardly matters. At worst, the parallax in a red-dot scope is not enough to move the point of impact out of the “shadow” of the dot. As one example, if the parallax error of a Brand-X red-dot scope is three-quarters of an inch at 100 yards, and the dot itself is 2MOA, then moving your head is not going to move the point of impact off of the dot. If the dot is on the target, you get a hit. And the parallax error may well be less than the accuracy limits of the ammo being used. So, the short explanation is: don’t sweat it. If a manufacturer tells you their red-dot is parallax free, it probably is. And even if it isn’t, you aren’t going to miss your target because of it. At least not this side of 300 yards.

Here, a Famous Maker 2.5-10X scope, in an Armalite mount, turns in an excellent group with Wolf ammo out of the S&W M&P-15. Bet against this combo at your peril, as it will kick your butt in competition.

The GG&G Accu-cam mount for the Aimpoint is fast, solid and easy to use.

Troy knows about the desire some of us have for a folded BUIS with the small aperture ready to go. They’re working on it.

The Troy rear, stood up and with the large aperture swung around.

The GG&G 3X adapter for the Aimpoint 3X optic. Fast, but you’ll need a pocket for it.

How red-dot sights work is also pretty much the same, with one big exception. Basically, a low-powered laser inside of the scope body reflects off of an internal plate that is partially-mirrored. The mirrored plate does not interfere with seeing through the scope. (But does explain why red-dot optics are often a bit dimmer than outside light.) You see the dot. You aim with the dot. At close range you use binocular vision, let the dot “float” and get your hits. At distance you mentally focus, see only the view through the scope, and put your dot on your target. The ability to look through an optic without seeing it is part of the “Bindon Aiming Concept.” The late Glyn Bindon figured out that a glowing dot against a black background was as good as transparent to the human brain when viewed with binocular vision. (Actually, our mind. Our brain is simply the mechanico-chemical processor of the thought processes of our sentience. But let’s not complicate things.) By looking “through” an otherwise solid aiming device, you could shoot quickly and still be accurate. Even though you can look through most red-dot optics, your mind is following the same pattern that Glyn figured out. Some competition shooters use this concept with magnifying optics. If they have a scope with a battery-powered or fiber optic enhanced aiming point, they will close the front scope cover on a magnifying scope. The result is an opaque optic they can aim “through” using the Bindon Aiming Concept. They get both a magnifying optic when they want it, and a red-dot when they need it.

The original AR optic, a Colt-procured 3X scope that fits on the carry handle. Better than nothing, but not by much.

ADCO

Adco scopes are mostly of the “tube you mount” type. And used for competition. But they make a pair of scopes that are more in line with what 3-gun competitors and defensive shooting types are looking for. First, the Solo. The Solo is a “heads up” type optic. Instead of a tube, it has a screen mounted at the front of the unit. The Solo is compact, and has built-in rails for mounting. The big advantage in the Solo are its reticle options. In addition to variable power in the display, you get multiple dot sizes, a “T” display and a bracketed dot. In a competition, you can be faced with many aiming needs. The ability to crank the power up, the dot size, and select other reticles, can be very useful. If you’re in a super-bright range (say, in the desert) and the targets are out a ways, you can select a small dot and high power. If the next match finds you in a heavily-forested range, and the targets are close in, you can dial back power and select the T or bracketed dot for maximum speed.

Mounting a red-dot (this Midwest Industries mount is for an Aimpoint) has become so popular that everyone makes mounts for them. Get a good one (this one is), make it tight, and paint it in.

GG&G makes an Accu-cam mount for the Holosight. Better than the knob.

The LaRue M-68 CCO or “gooseneck” mount gets the Aimpoint forward of any NVG you might mount.

The only hesitation any of my test-shooting crew have had is with its apparent fragility. I say apparent, because some of them worried that they’d break it. I haven’t, in months of shooting, and tossing cased guns in and out of my truck. But some of my testers could break a crowbar, and they worry. I’m not, and unless your job includes jumping out of perfectly good aircraft, I don’t think you need to either.

The Tactical looks like an Aimpoint. It comes with its own mount. The mount does not appear as strong as the mil-spec mounts others make, and the clamping knob and plate are not as large. But the Tactical is not made to be mil-spec. Why, then, get one? Simple: cost. The Tactical is entirely serviceable. I haven’t broken mine, and I’ve shot it on a bunch of rifles. I’ve put a lot of ammo through those rifles, including some really stout kickers. While I haven’t deliberately abused it, any rifle that my test-fire crew handles gets knocked around. While they’re careful, they still will be dropping rifles onto the shooting benches, banging gear against them, and occasionally whacking barricades with the rifles or the gear bolted to them. (Then there’s the whole “into and out of the truck” thing; loading up for every range trip.) The Adco Tactical has survived all that and still works fine. It hasn’t even changed zero. The suggested price of the Tactical is just under two hundred dollars. You’d be hard-pressed to buy just a mil-spec gooseneck mount for that. Add in shipping, and the mil-spec mount would cost more than the actual retail price of the Adco Tactical complete with mount. For the cost of the optic that you’d then mount in the mil-spec gooseneck, you could have bought two or three cases of practice ammo.

Which brings me once again to “Sweeney’s Equipment Paradigm.” The SEP tells us that when the choice is between the best gear, and gear that is good enough and money for practice ammo, then “good enough” wins the prize. If you buy the Adco, and the practice ammo, and actually learn to shoot, you’ll be far ahead of the guy who bought the “cool gear” and no practice ammo. If you continue to practice until the Adco breaks (And there’s no telling how long that may take. It might never happen.) you will always be one or more steps ahead of the guy who insists on only buying what the government buys. If at every step you buy gear that is good enough, and plow the difference into practice ammo, you’ll crush that other guy in every match.

The SEP is based on buying gear that is good enough, but durable enough. If you buy cheap, crappy stuff, it won’t work. Adco does not make cheap, crappy stuff.

It isn’t easy getting a photo through a scope meant for the eye, but here’s an idea of what the OSTI does for you. There’s a streetlight a hundred yards behind the camera.

The Bennie Cooley and Midwest Industries cantilever mounts both let you put a red-dot on a rifle with a carry handle.

Aimpoint CompM3

The first Aimpoint to gain military acceptance was called the M-68. We know it as the CompM2. Like the M2, the M3 is hell for tough. They both have parallax-free viewing, no broadcast light, and a whole host of makers who make bases for them. Not that you need others, as Aimpoint has their own base. (More on that later.) The CompM3 has five times the battery life of the M2. At the lowest visible setting it will run for 50,000 hours. On the lowest NVG setting it will run for 500,000 hours. For those math-challenged, that means just under seventy months for visible (five and three-quarter years) and just under seven hundred months for NVG. Basically, if you install a set of batteries, leave them on the lowest NVG setting, and put them in your gear bag, you will be retired, living in a warm, sunny clime, and looking at photos of your great-grandkids before you need to change those batteries. Fifty-seven years later. Yow! The CompM3 comes in two dot sizes, 2 and 4 moa, and is submersible to a greater depth than the M2, 135 ft vs. 75. For those who swim to work, the depth matters. For the rest of us it simply means they are waterproof to any rainstorm we’ll be working in. to further armor the M3, Aimpoint ships it with a rubber cover.

My favorite GG&G BUIS (and finalist for overall BUIS) is the MAD.

I’m not sure you could harm the LaRue BUIS with a hammer. With its QD lever you can have it off or on in a moment.

The Aimpoint base has a clamping knob with a ratchet and gear teeth in it. Once you’ve located the scope on the rifle, you simply tighten the knob until the ratchet slips and the rod clicks. That’s as tight as it will let you tighten it. If it works loose you can simply tighten again. At any time, you can apply tension to the knob.

If you see the ratchet start to slip, you know the base is still tight. With other tightening knobs you have to torque it down, and then mark the knob or shaft with paint drops. If your paint breaks, the knob is loosening.

However paint flakes off, or gets obscured by dust, dirt, or darkness. Even in the dark you can check your Aimpoint base by simply turning the knob until the ratchet slips and clicks. Aimpoint bases are all over the place in Iraq and Afghanistan. You can spot them by the longer shaft of the tightening knob. Some complain that the shaft is too long and gets in the way. Perhaps they’d like to design a new one on their lathe, one that is less obtrusive? (I’ll bet Aimpoint already tried that.) Me, I don’t even notice it.

If you’re a machinist or gunsmith, you can solve most any problem. Here’s an early solution to the problem of how to mount a red-dot scope to a carry handle: on the side.

The one shortcoming that red-dot scopes have is the lack of magnification. There have been some attempts at making 2X and 3X red-dot scopes, but they have not been well-received. What Aimpoint has done is make a separate magnifier. The 3X attachment needs its own base. It rides behind the Aimpoint (or other scopes, too) and simply magnifies your view through the scope. The drawback is that while the view is magnified, so is the dot. A 4-MOA dot viewed at one power with the naked eye, on a 100 yard target, seems OK. The same dot, viewed at 3X, seems too big. Optically, it is the same size on the target as it was before. But some object to suddenly seeing, what appears to their eye as, a 12-MOA dot. Me, I don’t care, or notice. You might want to try a rifle with the Aimpoint installed before you go out and get one, just in case it is something you might not like.

To mount it, Aimpoint came up with a trick mount. You clamp the base to the rifle, behind the M2 or M3. You clamp the adapter ring to the 3X optics. (You have to cut off the rubber cover on the front.) Clamp the adapter onto the optic. Then simply press the optic with adapter down onto the base post, and turn. The optic will rotate and then lock into place. To remove it, thumb the locking lever, turn the optic the other way, and lift. You will need a convenient pocket or pouch on your gear where you can stash the 3X and adapter. A compass pouch or bandage pouch, strapped to your load-bearing vest (if you’re geared up for SWAT or Fallujah) would be cool and convenient. Using a spare-mag pouch strapped to the buttstock for your 3X instead of a magazine could work. If you use some other spare magazine solution, then you’re all set. It isn’t an instantly-available solution, but the need for 3X magnification is not usually a close-range one. More likely you’re getting shot at from someone way out there. If they miss (and if they didn’t, you’d have other, larger, problems) then you can dig the 3X out of the pouch while you’re behind cover, and once it is mounted be ready to locate and deal with the bad guy.

The GG&G gooseneck mount for the Aimpoint is solidly made and will look good on any AR.

Samson makes a very cool 3X mount: it swings clear. Press the latch and the springs swing the 3X adapter off to the side. No need for a pocket. An additional advantage for competition shooters: a detachable mount, in USPSA 3-Guhn competition, makes the3X an extra optic. Boom, instant Open Division. However, if you use the Samson swing-adapter, your red-dot and the 3X are a single optic (equivalent to a zoom scope) and thus allowed in tactical Division. If you want the power, and either lose things or want to stay in Tactical, then you simply must have the Samson 3X adapter.

Mounts for the Aimpoint

With the government having bought something like half a million Aimpoints (as I was writing this chapter, Aimpoint received another contract, for an additional 160,000 scopes!) there is an impressive segment of the accessories industry devoted just to attaching Aimpoints to rifles. There are a number of reliable, solid mounts to choose from. GG&G makes a gooseneck mount with its own lever-clamping system. (Or a model without, if you distrust quick-detach mount systems.) The lever has a fingerloop at the front, and is adjustable. GG&G also makes a quick-detach mount for the 3X optics for your Aimpoint. The GG&G 3X mount rides over a folding BUIS, if the BUIS is low enough. Troy sights are. LaRue makes several mounts, the CCO68 and the gooseneck ’68.

The Aimpoint knob is viewed by some as bulky but solves a number of tightness issues for any combat arm.

Aimpoint makes tough optics. They must; they’ve sold literal truckloads to DoD.

Midwest Industries A2 sight folds down out of the way.

EOTech Holosight

The EOTech Holosight came about from basic research into optics. The sight works differently than others. On other red-dot sights, the internal laser sends a beam up to a reflector plate, a partially-mirrored internal (or external) screen. Your eye sees the reflected dot. On the Holosight, the laser reflect off of a diffraction grid. The grid then forms a three-dimensional image of the reticle as engraved/etched on the reflector plate. If there is enough surviving plate, you see the reticle. Where other red-dot sights lose effectiveness in rain or dirt, the EOTech doesn’t. As long as there is enough reflector plate unobscured (or undamaged) to send a visible amount of light to your eye, you see a reticle. Holosights work even when partially broken, muddy, rained on, and other indignities that other styles cannot work through. However, as we all know, you can’t get something for nothing. The miniature reticle pattern etched on the reflector plate, while offering redundancy in case of damage, means the reticle is grainy. Some shooters simply can’t reconcile themselves to the grainy image they see. The Holosight is also a bit bulky (although not much, compared to other units) and a bit heavy. However, the apparent heaviness is offset by the built-in mount. While the threads of the clamping bar are a bit to fine for my tastes, the Holosight does not need an extra mount. If you want one, however, GG&G makes a lever mount that replaces the EOTech screw. Once adjusted, it clamps the Holosight on with one movement of the lever.

You can have Holosights that use standard AA batteries, Lithium batteries, with dots compatible for night vision gear or not. The newest model, the 553, offers a built-in quick-dismount throwlever mounting system.

As I was working on this, EOTech showed me their proposed new magnifier. The base mounts behind the Holosight, and the magnifier snugs up against the rear of the sight. The one I had a chance to try was a prototype, and the production models will probably look a bit different. But for the fans of the Holosight, it will be a really good thing.

Zeiss Z-Point

The Z-Point is a compact battery driven red-dot sight. How compact? About the size of a prescription drug bottle, on its side, with a flat base. Very compact. Which is also its problem. As a sight by itself it is great. The view is bright and clear, the dot is sharp. But the center of the Z-Point view is too low. The view center of the Z-Point is about .875" off the top of the receiver. The line of sight of your BUIS is about 1.325" above the receiver. Not only can you not co-witness through the Z-Point, the line of sight for the irons is right on line with the housing of the Z-Point. Now, if we had a half-inch riser we could solve this problem. Without a riser the Z-Point is a wicked little backup sight on an Open gun, where you’d mount it on the side and tilt the gun to use the Z-Point on close targets at warp speed.

Meprolight

The Mepro 21 is another red-dot with a twist: it uses a triangle. Now, some love triangles, and some hate them. So you’d best try one before you spring for one. Me, I use whatever is there. The Mepro 21, with lever mounts, is easy to attach to your flat-top sight. Just open, slap on, close and zero. If it was already zeroed, and you get it on in the same slots, then you’re still zeroed. The Mepro 21 is fast in use. While looking at it, someone asked me “How long do the batteries last?” I had to pause for a moment before answering “About ten years.” No batteries. It uses Tritium and fiber optics to light up the diamond. In daylight the fiber optic pumps more light in, making the diamond brighter. In darkness the Tritium inside lights the triangle.

The Mepro 21 sits a bit high on the upper, but not so much so that aiming or cheek weld is a problem. Your BUIS will be visible in the lower part of the screen if you leave the Mepro 21 on to shoot irons.

Other Red-Dot Mounts

Not all ARs are flat-tops. Some have carry handles. Mounting a red-dot or other optic up there is not fun. So, more than one inventor has developed a cantilever mount. The rear of the mount clamps in the carry handle. The front drops down in front of the carry handle, hugging the handguards. You mount your optics out there.

The simplest is one like the California Competition Works rail, which is not adjustable. (At least not last I checked, but Bill Pallazzolo is a busy guy.) If you want a sturdy, straight-forward mount, you can’t go wrong. There are, however two others that add more: one from Bennie Cooley, and one from Midwest Industries.

When stood up, the MI sight gives you an A2 sight picture.

The Bennie Cooley (I mention it first only because I saw it first) cantilever has a dovetail in the middle, and you can adjust the front rail up or down. Why would you want to do that? So you can get a co-witness between your irons and your optics, even with the cantilever rail. If there is one drawback to the Bennie Cooley rail, it is that the clamping/adjusting screws are on the front. If you have your optic too far back, adjusting the rail gets to be a hassle.

The Midwest Industries rail is much the same thing, but the clamping/adjusting screws are on the side. You can mount your rail, then the optic, and adjust the rail up or down until it is perfect for your aiming style.

If you want optics, and can’t see the cost of a flat-top conversion (or upper) for your rifle, then one of these rails lets you get optics on.

The Aimpoint with the twist-off 3X adapter, being used to slam LaRue targets far downrange.

BUIS

The Back Up Iron Sight is the inevitable result of scope development. As good as scopes are, as durable as they are and despite the advantages the give us, iron sights can’t be done away with. Scopes break. Batteries die. With iron sights ready on the rifle, you can stay in the fight. Here in the Midwest it gets very cold, and in a lot of locations, quite damp. A battery dead from the cold makes a red-dot sight useless. A rained-on, snowed-on or breathed-on scope is impossible to see through. So, having taken the carry handle off (and the sight that went with it) to install a scope, we’re now putting iron sights back on.

The need for back-up iron sights comes about as a result of the evolution of optics. Back in the old days, optics, or scopes as they were more-often called, weren’t durable enough for military use, a situation that many hunters found amusing. “Why, I’ve hunted with this scope for twenty years, and it has never given me a problem.” Uh-huh. And in all that time, how often have you dropped it? Or had to dive into a ditch to avoid incoming artillery or rifle fire? No, scopes for a long time in military use were pampered snipers sights (the sights were pampered, not the sniper) and not depended on for general issue.

IPSC changed that, as it has for so many things firearms related. More than a lot of people are willing to admit. The beginning came in the very late 1980s, by way of a shooter by the name of Jerry Barnhart. IPSC shooters are a peculiar kind of competitor, and American competitors are unlike any in the world. Jerry (as are so many IPSC shooters) is a nice guy. He’s also dedicated, analytical, driven and likes to win. He determined that a scope just might give him an advantage, if he could figure out the right one.

What he settled on was one of the earliest versions of the Aimpoint. Now Jerry wasn’t the first to ‘scope a handgun. The late Dean Grennell, and J.D. Jones, had been putting scopes on handguns a couple of decades earlier. But what Dean was doing was to wring more accuracy out of target guns. J.D. wanted scopes for hunting. Neither application made the demands on scopes that IPSC shooting did. Target shooting was done with really soft-recoiling ammo. Hunting (at least as done by J.D. Jones) involved very powerful rounds. But even the most dedicated hunter wasn’t gong to be shooting more than a few hundred, at most a thousand, rounds a year. The competition loads in IPSC involve the .38 Super. (At least in Open Division.) The recoil and vibration of a .38 Super at Major are intense. Back then, the formula was a 125-grain bullet at 1,400 fps, or a 115 at 1,520. Not bad, you say? Fine, then consider doing that twenty or thirty thousand times a year. IPSC shooters can wear out guns, something that few other competitive endeavors can claim. Jerry mounted an early Aimpoint, won the 1990 U.S. Nationals, and started the trend. Not to be out-done, Doug Koenig took his Aimpoint-equipped handgun to the IPSC World Championships later that year and won the 1990 World Shoot with it. After that, the floodgates were open; no one wanted to shoot iron sights any more.

That was with handguns. USPSA/IPSC 3-gun competition didn’t get organized at the National level until the 1990s, but my club and others were doing it in the early 1980s. What we found was that a lot of cheap scopes couldn’t take the regular volume of shooting we were doing.

The red-dot sights a decade later were not up to it either. Depending on the exact load, the scope mount used, and the luck of the shooter, optics died (the dot expired, flickered, lost zero) after a week, a month, or if you were really unlucky, a few days. The year before the “Blackhawk Down” incident in Mogadishu, one of the Rangers who would be there was in my squad at the Nationals. He had a supply of scopes for his Open gun sufficient to get him through the match if one croaked each day of shooting. But scopes improved. By 1994, I found myself at the Michigan Tactical Officers Association annual conference looking at a new scope by EOTech. It was scaled down from holographic three-dimensional sighting systems for aircraft. It was slick, promised to be durable, and would be available soon. I asked them if they were planning on getting into practical shooting. (I had two goals in mind: to find out if they knew what they were getting into, and to see if I could score a sight to write about.) “Yes, we’ve got a shooter who is going to be using our optics. Jerry… Barnhart?” So much for beating the rest of the guys to the punch.

Showing just what a red-dot, or any optic, looks like on target is next to impossible. The human eye is so much better than any camera that trying to take a picture is almost futile. That doesn’t stop us from trying.

Just a short while ago, an AR with a red-dot scope on it would have been sneered at as “too gamey” and “not tactical.” If you look closely, you’ll see the EOTech and laser are lashed down with 550 cord. Spc. Anthony Noger, from Company B, 1st Battalion, 325th Airborne Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division on patrol in Tal Afar, Iraq. DoD photo by Staff Sgt. James Harper Jr.

It took a few years, but optics makers developed the manufacturing methods ands optics designs that allowed them to make durable scopes. We now have optics so durable they can be mounted directly on a slide. Durable enough that they can be general-issue in the military. However, that brings up another problem: where to put the optics. For many years we had two choices, both bad: you could mount the scope in a base and rings clamped in the handle. Colt even offered a scope for mounting right there. (They didn’t make them, they had an optics company make them, and marked them with the Colt logo.) Or, you could whack the carry handle of the upper receiver off, bolt a Weaver base on, and mount the scope there. The carry-handle mount problem is that the scope is too high. Your face comes off the stock in order for your eye to see through the scope. Without a solid check weld, aiming is difficult, and fast aiming is very difficult. Cutting the handle off had the dual problem of what do you do with a rifle no-one else wants, and how do you get irons back on if the scope croaks? Unless the Weaver mount conversion was perfectly done, it ended up ugly and weak. And there was no way to get iron sights back on. Luckily for us, Colt solved that problem. They made rifles with a Weaver-like base (called a picatinny rail) as an integral part of the upper receiver. Scope bases, or scopes with built-in bases, could be bolted right to the receiver.

But we still had the problem of what to do if the scope breaks. I know, someone is asking “If IPSC perfected the red-dot optic, then why worry if it breaks?” The best response is something that my friend John Farnam once described: “Put two Marines in a room, each with a ball bearing. Come back in fifteen minutes. One ball bearing will be broken, the other missing, and neither Marine will know what happened.” Even outside of combat operations, the military is hard on gear. Add the stress of being shot at, and all sorts of equipment gets broken. A red-dot scope makes your shooting faster and more accurate, but not if it is broken.

Thus, the back up iron sight, or BUIS. The ideal BUIS would be compact, durable, out of the way and quickly brought into action when the scope is toast. The ideal scope would survive anything. Failing that, then the ideal scope is one that will survive most anything, and when it doesn’t you can easily take it off. The best way to keep the BUIS out of the way of the optics is to have it fold. The best way to get the scope off when it breaks is some sort of quick-detach or hand-unlocking mount.

There are BUIS that do not fold, and they are perfectly acceptable. They just get in the way a bit with your sighting through the optics. Some prefer a non-folding BUIS for the extra measure of durability. Me, I’d rather have something folded (which will be very durable, since it has nothing sticking up) that doesn’t get in the way of my view through the optics. Folding BUIS depend on a pivot pin, some in springs, many on a locking button of some kind. All those small parts can break. The non-folding sights have small parts, too, but their small parts are fewer in number and are not used to hold the iron sight upright. Which one you select depend on your needs, your budget, and for some what is the “uber-cool” sight of the moment. More than one shooter has been known to select a bit of gear by what they have seen in a photo from Iraq or Afghanistan.

A Colt M4 with a railed handguard, Aimpoint with Aimpoint mount, and a Matech. Dusty, worn, scratched and still working. Pvt. John Robinson and fellow Soldiers from Company A, 1st Battalion, 187th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division search houses for terrorists in Baji, Iraq. DoD photo by Spc. Charles W. Gill.

Two things you need to be aware of about BUIS: You must zero them as you do any sight, and you must be sure you install/replace them to the same spot each time. I’ve had shooters install a BUIS on their rifle and not zero it. No manufacturer can guarantee that simply bolting their BUIS on will ensure you’re sighted in. You still have to do the hard work. And, despite the top rail of a rifle being one piece and machined as precisely as possible, moving it to another slot may change your zero.

In one of the classes we once had an officer suddenly experience a change in zero in his rifle. After a little investigation, we discovered that he’d removed his carry handle/sight, and when installing it had clamped it on one slot back. That was enough to throw off his zero.

The new EOTech magnifier, in prototype form.

M4 Carry Handle

The original BUIS is the carry handle off of the M4. You take it off (after zeroing it) and stash it in your gear. When you need it you yank off the optics, install the M4 and go to work. For those anticipating a split-second assault, the whole affair seems pretty slap-dash. You can’t be certain of your zero, it takes time, and where did you stash that sight, anyway? It works well enough that I’ve read more than one account of a soldier or Marine having to go through exactly that process, for a good end result. One even had his buddy throw him a carry handle/sight. In a military context, “close enough” often is, fights are not always over in a few seconds, and equipment breaks. The use of IEDs (Improvised Explosive Explosives) in Iraq has lead to more optics being busted. To no one’s surprise, people have a higher survival rate to nearby explosions than electronics or optics. A solder or Marine may be momentarily stunned by an IED, but his optics often are toast. With iron sights to use, he can still fight. The carry handle gives him/her that option. As bad as the city of Detroit was, there weren’t any IEDs written up in the papers or police reports. However, sudden attacks were and still are common. (Not as much as in the past.) There, as with many civilian defensive encounters, you may not have the time to dig a carry handle out of your gear (if you even have it along) and so a bolted-on BUIS is the preferred solution to busted optics.

Me, getting to shoot the new EOTech Holosight and magnifier. Trust me, you’ll want one when they become available.

A.R.M.S.

Atlantic Research Marketing Systems makes gear that defines cool. Calling their S.I.R. a railed forearm is like calling a humvee a pickup truck. The 40 and 40L sights ARMS makes go about the process of standing up a bit differently. Where most sights must be pushed up, the ARMS 40 and 40L are spring-loaded. Move the locking lever and the sight pops up on its own. It remains spring-loaded but unlocked. If you bump it, it swings back but then stands upright again. The 40L is the low-profile version that blends in with the top rail of the SIR. In order to blend it has to be lower, and the adjustment parts thus smaller. It can be hard on your fingers to get the sight zeroed. But once set, you won’t have to touch it again. The #40 is the standard A.R.M.S. sight, and for many shooters it’s the definition of cool.

LaRue

The LaRue BUIS is a serious contender in the “brother-in-law with a ball peen hammer” survivability contest. A relatively simple upright machined housing protects the sight and its adjustment knobs. As with all LaRue products it is designed and built to be tough. The LaRue is windage adjustable without tools. Not everyone wants a folding BUIS, and for those individuals the LaRue is a damned good choice.

LMT

Lewis Machine & Tool is a basic manufacturer of things AR. That is, they make the rifles that other people sell as “made by XYZ.” They also make rifles for themselves. Their BUIS appears to be a modified detachable carry handle. Lest you think making a BUIS this way is a cop-out, let me assure you it isn’t. First, making one from a handle forging, while it requires some extra fixturing in the machining process, produces a first-rate product. It is as durable as the handle/sight would be. It uses the same parts, so if you need to rebuild or want to replace something, standard A2 parts are what you’ll need. And, as an A2 sight, if you know how to work the sights on an A2 AR then the LMT BUIS will hold no mysteries for you. You also get ranging adjustments with the LMT. Once you’re zeroed, you can click up to a longer range, just like the A2.

The EOTech Holosight is a durable red-dot with a “circle and dot” reticle, like a fighter jet sight.

The rail on your flat-top is made by forging a rib on top of the receiver and machining the picatinny rail. The dimensions are not the same as earlier weaver-base conversions.

GG&G

Based in Arizona, GG&G makes a number of BUIS, two of which concern us. One is the MAD, or Multiple Aperture Device. The MAD is a folding sight, with a paddle-like sighting arm. Inside the arm is a wheel with four apertures; two big, two small. With a quick twist you can have a large aperture or a small one. The MAD came about from a Naval Surface Warfare request for sights with multiple size apertures that were in the same location in the sight. The old A1 sight had two apertures, but one was a long-range sight. The MAD is a low-profile sight, and will fit under many magnifying optics. You can have a scope in a quick detachable mount (Like the LaRue we’ve tested) and have irons underneath. If the scope goes toes up, or you have it off for cleaning or protection, your irons are right there. The MAD offers no ranging adjustment. You adjust your zero using the old A1 sight method: vertical in the front sight, and horizontal in the rear. The horizontal adjustment moves the whole MAD paddle. The MAD is low when folded, and durable. The older MAD sights flipped up and down. Newer ones lock upright, and you have to press the lock button to unlock it and fold it. A locked upright sight is an Airborne requirement. Yes, a folding sight is more compact, and less likely to injure an airborne trooper, but if it folds down when it gets bumped, it isn’t much use. Many early designs of folding sights (and some still) didn’t lock up. But many now lock upright.

The DPMS Mangonel, front, stood up.

The DPMS Mangonel rear.

The GG&G A2 is not a compact as the MAD, but uses many A2 parts. It locks up, and the windage adjustment knob works directly on the aperture, like the A2 sight. It does not offer ranging settings.

Matech

Matech makes what one contact in the Armed Forces has told me is the “Air Force sight.” I don’t know about that, but I do know that they have an open-ended contract for twenty thousand sights a month, and I see them in Iraq photos all the time. The Matech differs from the others in several respects. The housing is a steel casting, not an aluminum machining. The sighting stalk with its aperture folds down, and when upright is simply a short stick. The Matech has ranging capabilities. The left side of the Matech has a paddle, with a set of range figures on the side. Crank the paddle until the range indicator corresponds to the distance you need. No clicks to count, just the actual range number. On a target range, you want clicks, so you can count and be dead-on. In a firefight, all you need is someone with a laser rangefinder to shout out the distance, set your Matech, and off you go. While the Matech is lower in profile than many, like the GG&G and Midwest Industries A2s, is isn’t as low as the MAD.

The rear sight on this FG-42 isn’t a BUIS, as there are no optics.Those came later, and on this same model rifle.

Midwest Industries

The MI A2 BUIS and the GG&G are examples of convergent evolution. Yes, they look the same. But look at it from the viewpoint of a designer: you need a locking block, with crossbolt and clamping plate. You need a hinge and a sight. You need ears to protect the sight, and you need to round the edges so your customers don’t cut themselves on our product. The remarkable thing isn’t that two look alike, but that so many look different. The MI A2 has a different texture and color to the anodizing, and slightly different lines in its parts. But it is a folding A2 sight with two apertures, and works just like you’d expect an A2 sight to work. As with the GG&G, the MI is not as low-profile a sight at you can have with other designs. It is however, tough, it comes back to zero when folded and re-stood, it looks good, and stays put.

DPMS Mangonel

The DPMS Mangonel is a different approach to the BUIS. Instead of a folding assembly that then locks or is spring-loaded, the Mangonel has a spring-loaded locking bar. Lift the front or the rear and the locking bar lifts until it locks into the latching slot. The Mangonel lays flat, but is positively locked when it is up. The front is adjustable for vertical and the rear for windage. There are no protective wings for the rear aperture, but then for a BUIS, do you need them? We aren’t talking a 600-yard target sight here, but something to keep you in the fight (or the match) when your optics croak on you. One thing you must be aware of: the Mangonel front has two locking slots. If you pop your front sight up and you get the locking slot that causes your sight to ride lower, you’ll be shooting over your target. Why two slots? One for gas block rail mounting, and one for railed forearm mounting.

Troy

Troy Industries makes folding front and rear sights. They are the ones the S&W selected for their rifle, and a lot of other people have elected to go with Troy, too. The Troy rear is windage adjustable, and the apertures are on a paddle that swings back and forth to get you from the large to the small. They are durable, compact, and good looking. The Troy rear BUIS is the one I went with on my DMR.

Yankee Hill Machine

The YHM BUIS is the one Al Zitta uses, and they have a lot going for them. They don’t fold as compact as others, but they can be folded with the small aperture ready to go instead of the large one.

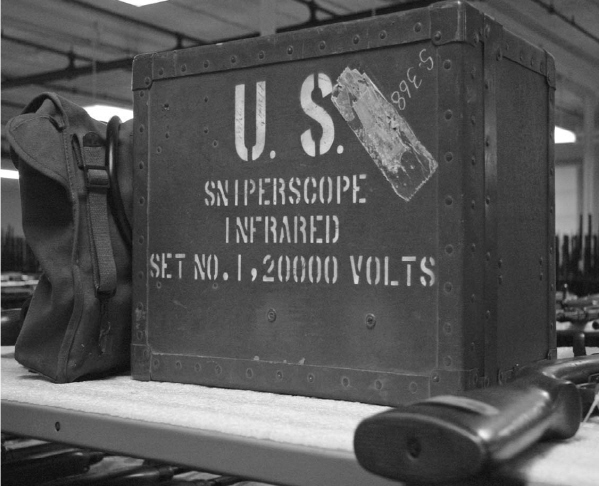

The original night vision scope was active (the enemy could see your light), not passive. And large. This storage box for one should give you a clue. (That’s an M1 Carbine next to it.)

Armalite

The Armalite BUIS looks a lot like the rear sight on the WWII German FG-42: a post with a vertically adjustable aperture in it. The idea works mechanically, but to have it you have to give up the option of other aperture sizes. So if you do not like the one that it comes as, you’ll have to have your gunsmith disassemble the sight and bore out the aperture to the size you prefer. However, that is a small detail for a sight that works well.

As a sight by itself, the Zeiss is great. But you’ve got to have irons, and the Zeiss “doesn’t play well with others.”

BUIS Apertures

One thing that makes me a bit crazy is the apparent universal idea that when you need a BUIS, you’ll want the large aperture. Me, I want the small for most anything. The large is best used for night shooting, and usually in a military context. In a law enforcement use, or defensive non-LEO use, the large is a bit coarse. However, you cannot fold most BUIS down with the small aperture ready to go. The YHM BUIS lets you do that. Some of the others (A.R.M.S. for one) can do that if you file off the top of the small aperture ring. I’m not cool with that, so I’ll have to wait. Troy tells me that they know about some shooters who have the same crazy idea, and they’re working on a way to make it so you can have either aperture selected and still fold the sight.