38.

■ Outside the Myrtle Gallery bystanders caught the mood of the scene. At the bus stop, hens with king-size cigarettes were clucking. Two mums with prams had pulled to a stop and were looking gingerly towards the building. Chivalrously, a young man in a suit ran across the gravel and into the gallery. Liska’s pictures had been reabsorbed into the private realm, where only she would know them, and now the gallery needed emergency cataloguists and critics. Most of all, journalists would have to be rushed in.

I walked towards the North Deeside Road, dripping water. Suicide was never going to happen for me, even though blackness still pervaded my days. The comedy of life was too good to miss. The only fierce impulse that had risen within me in days had been the one to destroy those paintings, and I’d been unable to act. I’d wanted to do it but someone else had done it for me.

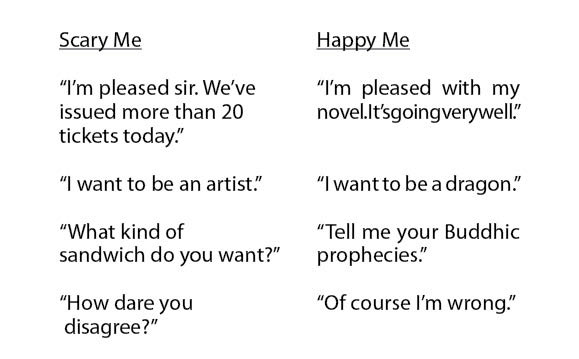

This was Scary Me replaced by Happy Me.

I looked along the road but the young couple with the flame-throwers had departed. Vehicles belted out towards the satellite towns and there I stood and dripped. The enormous ox of a road-transporter ran past me, and the turbulence rocked me from side to side. Although the vibrations of the vehicles rattled my head, I could still think clearly. This time I resolved that the next chance I got to act, I would.

As readers whom I’m sure share with me the most acute sensitivity to a fellow being’s mental discomfort, you will not have failed to have been touched by this most moving of episodes. It is, I think I am right in saying, the first time since Mrs Winston Churchill destroyed Sutherland’s portrait of her husband, that a member of the public has evinced clear signs of mental anguish by taking aggression out on a painting.

I walked back to the city as the roadway quietened for the night. Head down, I travelled the carpet of paving stones, past shops with increasingly illegible names, and back to Aberdeen. I was damp and my legs were cold where my trousers had stuck.

Parry let me into his house but said nothing, and then he went out for the evening, leaving me in a sulk. On the coffee table was the only sign of upset, an empty bottle of wine from the night before and a dark cup of coffee from the morning. The television was speaking patiently to itself and I removed my trousers and crumpled them. I took off my shirt and held it up.

All shall be flat and without a crease, I thought. Tomorrow all will be new and I will start again.