On a mid-November morning in 2009, an architect, two lawyers and the president of a beer company stood on a section of McMicken Avenue sidewalk arguing about the dates and order of events that led to the repeal of Prohibition. Over the past few decades, the streets of Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine have gained a reputation for a number of activities. Spontaneous academic debate is not one of them, but this group of amateur local historians was waiting to see what a couple of amateur urban archaeologists were going to find underneath the sidewalk in front of them.

The backhoe was two hours late, but eventually the large diesel truck pulled up, dropped its loading ramps and started backing a large piece of excavation equipment onto McMicken. Dump truck and backhoe assumed their positions, hurricane fencing was wrapped around a tree and some poles to block off sidewalk traffic, the small group of onlookers stopped arguing and assumed a safe distance and the dump bucket made a multiton tap onto the sidewalk’s concrete surface. Roughly ten minutes later, the backhoe firmly snagged its claws on a sheet of broken concrete, lifting one edge a couple feet from the surface. Everything stopped. The operator climbed down from the equipment. The onlookers moved forward. The mystery of what lay underneath was about to be revealed.

In most city neighborhoods, pulling back a piece of concrete to look underneath it would involve a lot less suspense. In most places, the decision to pay several thousand dollars to unload heavy equipment onto a downtown street for the purpose of ripping up the sidewalk—without a permit—could be viewed as proof of mental instability, but Over-the-Rhine is not most places. Building owners Doug and Mike Bootes may be the first to call this adventure in urban excavation a little crazy, but it was also based on recent discoveries, a series of mathematical calculations and a gnawing mystery that anybody with a good sense of curiosity should understand.

Mike Bootes lives in one of five buildings that used to be part of a commercial brewing complex. The Bauer Brewery was founded on the site in 1865. It changed hands and operated for only a year as the George Bach Brewery in 1874 and then was sold and became Schmidt and Prell Brewery in 1876. It stayed with members of the Schmidt family, subsequently becoming Schmidt and Brother Brewery and Schmidt Brothers Brewing Company, until it was sold in 1905. For its remaining life as a brewery, it was known as Crown Brewery, named after the Crown Beer that had been the brewery’s staple product during the Schmidt years. The brewery never became one of the city’s largest, but the different eras and architectural styles of its buildings show its expansion over time, and it stayed in business roughly sixty-one years. The brewery was composed of two connected buildings on the north side of McMicken (including the Booteses’ residence) and three connected buildings on the south side (all three on the south are connected and referred to collectively as “the south building”).

The Schmidt Brothers Brewery had several features common to Cincinnati’s nineteenth-century breweries. The location on opposite sides of the street is both inconvenient and almost universal. The federal government imposed a tax on beer production to help pay for the Civil War, but unlike previous alcohol taxes, this one stayed in place and its terms became burdensome when breweries started to make bottled beer a more significant part of their businesses in the 1870s and 1880s. The tax levied one dollar on each barrel. As a number of innovations were making bottling much more feasible in the 1880s, the required means of paying the tax was still a stamp that had to be physically placed on the barrel itself. “Barrel” wasn’t just a measurement of volume; it meant an actual wooden barrel full of beer. Afraid that bottling would circumvent the tax, the law required that bottling facilities be separated from the brew house, with no physical connection. In 1890, somebody—and many sources speculate that the “somebody” was Frederick Pabst—convinced members of Congress to change the law. New processes for gauging and monitoring volume were imposed, and it became legal to connect the brew house to bottling facilities with a pipeline.

The south portion of Schmidt Brewery as it appears today at 133 East McMicken Avenue. These three buildings illustrate changes in ownership and expansion ranging from the establishment of the Bauer Brewery in 1865, through Schmidt family ownership between 1870 and 1905, through the demise of Crown Brewery during Prohibition.

At its peak, Over-the-Rhine was home to tens of thousands of people. It was the center of German-American culture in Cincinnati and also became home to the seedier side of the city’s social and political life. It was home to hundreds of saloons. For most of the nineteenth century, the neighborhood had over a dozen breweries operating in or near its borders and dozens of ancillary businesses that served brewing and the saloon trade, as well as hundreds of other businesses and industries. Over-the-Rhine was one of the most densely populated neighborhoods in America, and it would have been hard to move around in. Trying to operate a business by constantly crossing a street full of people, horses, wagons and early motor vehicles would have been challenging, and McMicken was a major artery, once serving as the primary road heading west out of town. Imagine the modern equivalent of having to leave your office and push a cart full of paper and supplies across a busy city street every time you needed to make copies. That’s what moving keg beer across the street to bottle it must have felt like, so breweries with any degree of bottling capacity dug connecting tunnels when the law permitted them to do so.

The proliferation of breweries and saloons in Over-the-Rhine was driven in large part by the creation and proliferation of a new type of beer called “lager” in the mid-1800s. Lager required a longer brewing process. In fact, the term “lager” is a derivative of a German word meaning “to store.” This type of beer also required cool temperatures. Prior to artificial refrigeration, breweries needed a way to keep lager beer chilled during brewing. The most common answer to creating a chilled environment without electricity was to dig cavernous subbasements that either went thirty to forty feet underground or back into McMicken’s steep hillside to reach cavelike conditions. These arched cavernous rooms, called “lagering cellars” or the German “felsen” tunnels, created a roughly constant fifty-five-degree environment. Copper pipes run along the walls and ceilings of lagering cellars circulated brine, ammonia or cold water in a crude, early version of air conditioning to bring temperatures down to about forty degrees. When the brewing complexes could be connected, breweries built tunnels underneath the city streets (below sewer or municipal waterlines) connecting their subterranean chambers.

Iron and steel brackets remain rusting in the humid subbasements. Brackets would have originally held lines carrying chilled water to help refrigerate the lagering cellars. The bracket pictured may also have carried beer lines from the brew house to the bottling facility. No piping remains in any of the known lagering cellars, probably reused decades ago.

After its demise, the Crown Brewery was devoted to other commercial uses. It became a plumbing supply company and a decorative plaster manufacturer. Lagering cellars had a number of air shafts to regulate humidity and holes for piping beer between different parts of the brewing process. When the breweries ceased to be used as breweries, the cellars and tunnels were closed, and almost all of them were sealed in the intervening years, just leaving holes in basement floors leading to “nowhere.” It became common practice to use these entrances to the subterranean Over-the-Rhine as garbage holes, which is what both the plaster business and plumbing supply business did with them. The plumbing company started chucking broken and discarded fixtures down a large opening that led from the first floor, through the basement, to the subbasement lagering cellars below. Over the years, the subbasement chamber at the bottom of this hole accumulated a mountain of broken porcelain, which reached to the top of the chamber and blocked entrance to the subbasement. Throughout most of the neighborhood, these subbasements were sealed entirely, which was the approach taken by the former owners of Mike Bootes’s property, leaving an intriguing cinder block arch in the side of his stone basement wall.

Ted Love bought the Schmidt Brothers southern building in the summer of 2008. Love succumbed to his curiosity rather quickly and hired a crew of laborers to remove the discarded plumbing parts from the entrance to his subbasement. Hauling out construction dumpsters full of porcelain allowed Love and his crew to become the first people to walk into the subterranean lagering caverns in decades. The exploration also revealed an oval, stone tunnel that exits the subbasement chambers and travels under McMicken Avenue to the Bootes property. At basement level, the crew also broke through a brick wall into an arched room immediately under the sidewalk but sealed and forgotten for at least a generation.

On the other side of the street, Mike Bootes started poking holes in his mysterious cinder block arch. Ted Love’s crew had removed bricks and found vacant, empty space. Mike’s experience was different: a torrent of loose fill started pouring into his basement. Mike, his brother Doug and the friends that they had gathered to celebrate Doug’s birthday by smashing a hole in their basement wall stood back and watched a seemingly endless river of dirt, gravel, broken bricks and small pieces of concrete flood out of the hole and onto the floor. They waited. They drank some beer. They waited, and hours later a trickle of fill was still tumbling out of the hole. Someone finally asked, “I wonder if the sidewalk will collapse?” Good question. Nobody knew the answer.

Ted Love’s tunnel under McMicken ended in a pile of bricks, roughly ten feet away from and fifteen feet below Mike Bootes’s dirt-spewing archway. What lay between, and how these spaces connected, remained unknown. Less curious people might have cleaned up their basement floor, patched the hole and lived a happy life with that mystery remaining unsolved, but neither Mike nor Doug Bootes is one of those people. The curiosity drove them to hire a backhoe to start pounding a hole in a Cincinnati sidewalk.

As the backhoe claw lifted its first sheet of sidewalk, the crowd moved forward to look into the hole. It was clear that the sidewalk had been poured on forms atop very old steel beams and that at least part of the space underneath was hollow, but it was also full of dirt and brick fill. Bootes made the call: “Keep digging.” Forty-eight hours and a lot of work later, a roughly twenty-by ten-foot chamber under the sidewalk—or, more accurately, where the sidewalk used to be—had been completely excavated. The chamber essentially mirrored the one at basement level across the street, with one significant difference. As the last of the fill was shoveled off the floor by hand, the top of a graceful stone arch started to become visible at the bottom of the basement wall. The area in front of it showed a cut in the stone floor filled with loose, sandy soil. Obviously, this was the filled-in entrance to whatever space connected the tunnel under McMicken to some area below Mike Bootes’s brand-new yet over one-hundred-year-old basement addition, but there was still an unknown area separating several feet in distance and about fifteen feet down. The stairs could lead straight to the tunnel, or they could lead to another subbasement chamber where the tunnel connected. This question would have to simmer a little longer.

City of Cincinnati staff are, on occasion, accused of diligence. It was on one such occasion that a building inspector utilized his expertly trained eyes and professional knowledge to conclude that there was something amiss about the fact that a twenty-foot piece of sidewalk on a downtown street had been replaced over the weekend by a fifteen-foot-deep hole, surrounded by bright orange hurricane fence. (Taxpaying Cincinnatians might want to believe that staff in a lesser city would have missed this subtle irregularity.) So Mike Bootes obtained the appropriate permits, engineering and architectural documentation, etc. and spent the next several weeks replacing the sidewalk.

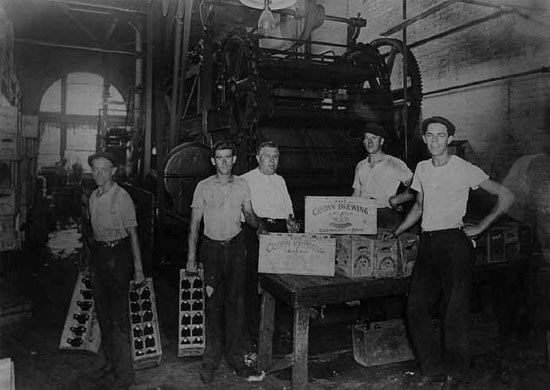

Workers inside the Crown Brewery in the early twentieth century. This photo appears to have been taken in the northern half of the brewery, in the building that currently houses Superior Rubber. Courtesy of Steven Hampton, president, Brewery District CURC.

On New Year’s Eve 2010, over a dozen volunteers gathered in Mike Bootes’s basement with shovels, buckets and a bunch of beer with a mission to connect the Bootes property with the McMicken tunnel somewhere roughly fifteen feet below. Alternately taking turns in the hole where the stairwell used to be, a crew more accustomed to manning bar stools at Murphy’s Pub did the backbreaking work of passing bucket after bucket of dirt and stone out of the hole. An assembly line system of beer laborers got wheelbarrows full of debris upstairs and pushed them down Hust Alley to a vacant lot. As drug dealers on East Clifton watched this constant procession going up and down the alley, undoubtedly wondering what kind of weird New Year’s Eve celebration this might be, the crew in the basement broke through to the other side a few hours before the end of 2009.

What’s most interesting about the Schmidt Brothers excavation is not that a guy would become so overwhelmed by curiosity that he would haul tons of broken porcelain out of a subbasement before patching his roof, or that the same motivation would cause his neighbor to start ripping up a city sidewalk without permission. What’s most interesting is that the Schmidt Brothers story has precedent, and it is unlikely to be the last subterranean world rediscovered in Over-the-Rhine.

Chris Frutkin and Fred Berger bought a building that used to be part of the Kauffman Brewery in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Chris and Fred are both in the real estate development, rental and management business, and they bought the building in the early 1990s to convert the industrial space to loft apartments.

The real estate agent who sold Chris and Fred the building had also sold it to previous owners. About a year after the sale to Chris and Fred, the agent decided to retire and was cleaning out old files. In the file from the 1956 sale of the property, he found architectural drawings of the Kauffman brew house (not copies, but the original architectural drawings from the 1880s construction). The agent was thoughtful enough to give the copies to Chris. As he looked them over, he became more intrigued by what the plans showed. Neither Chris nor Fred is an architect, but they have both been around enough development to be able to read architectural drawings, and even someone who lacks this skill can identify the fact that the drawings showed an additional floor to the building that was no longer known to exist. At first, they assumed that plans had changed during construction; but upon closer examination, another possibility emerged.

Chris went down to the basement with a sledgehammer and knocked a hole through a sealed archway. In most basements, this would lead to dirt. In Chris’s, it led to a tunnel that wrapped around the sides of his basement and that had been sealed for decades. Exploration continued. In the tunnel, Chris found a hole. In the hole, Chris found an extra eleven-thousand-square-foot building that he didn’t know he owned—below the basement.

John Kauffman’s Vine Street brewery was one of the more successful in the city. It opened in 1860, rose to be the fourth largest in the city by 1871 and remained in business until Prohibition shut it down in 1919. The brewery had two tunnels connecting it to part of the brewery complex on Hamer Street, behind Vine, one at basement level and one at the subbasement level that Chris found when he crawled through a hole in his basement in about 1994.

The Kauffman brewery building story illustrates a uniquely Over-the-Rhine phenomenon. Where else can you find an eleven-thousand-square-foot building underneath your building? The portion of the former Kauffman brewery on Hamer Street was best known to Cincinnatians for decades as the Husman Potato Chip factory. The tunnel under Hamer Street leads to five subbasement felsen tunnels underneath the former Husman factory. Structural and environmental analysis of the building done during Husman’s ownership is free of any mention of these tunnels, suggesting that the company operated there for decades with no knowledge that it owned thousands of square feet of building underneath its basement.

Subbasement cellars were used for more than beer production. The Kauffman brewery also built a large apartment building for workers at 1725 Vine Street that contains large subbasement cellars that were used for beer storage. Providing free or reduced-rate rent to workers was a typical part of nineteenth-century brewery employment, and other breweries owned housing. Many of the lagering cellars and tunnels became obsolete while the breweries were still in operation because of the advent of artificial refrigeration in the mid-1880s. In subsequent years, the spaces would have been of limited use, and after Prohibition they would have been little more than a liability—particularly in residential properties. When different parts of brewing complexes were sold to different owners, it would have been undesirable to have tunnels connecting them. There is also speculation that some of the cellars and tunnels were used to produce and transport beer during Prohibition. Although this is unsubstantiated, it makes sense. What better place for an underground brewing operation than literally underground—in space constructed for the purpose of brewing? For all of these reasons, Over-the-Rhine’s underworld was sealed off, forgotten and may have been intentionally hidden during the 1920s.

Cincinnati’s brewing industry didn’t fade away. It was forced to an abrupt halt, and a lot of brewery real estate was sold in the first few years after Prohibition as the businesses folded and the corporations dissolved. The past was literally sealed under basements and through bricked or blocked-up stone archways by a generation of people who are almost entirely gone. As a result, these spaces continue to be found. When the Alms and Doepke Park Haus garage was built at the corner of Reading and Sycamore, filling in the massive lagering cellars under the demolished site of the Gambrinus Stock Brewery in a way that would have supported heavy construction above was so daunting that it was easier to build concrete piers to the bottom of the former brewery’s subbasement and construct the five-story parking garage on top of them. Even many known spaces contain unknowns. A subbasement under part of the former Sohn Brewery on Stonewall and Mohawk Streets is open, but an artesian well at the bottom and a deteriorated ladder have left the space unexplored for decades; and stories persist of unfound and extensive tunnel networks. Former Jackson Brewery building owner Denny Dellinger was told by stewards of the building decades earlier that they had found tunnels exiting the building’s massive lagering cellars and traveling so far that they turned back before they found an end. Dellinger, an architect, was unable to find these legendary tunnels but says that the original architectural drawings for the building indicate that they might exist and a number of archway patterns in the stone walls raise the question of whether doorways were sealed with stone in the years intervening between the fabled journey through an extensive tunnel and Dellinger’s twenty-first-century purchase.

George Weber’s Jackson Brewery as it appears today.

The Jackson Brewery tunnel legend is probably just an urban Cincinnati myth, but it is also very likely that there are subterranean spaces in Over-the-Rhine that remain unexplored by a living generation. Brewery buildings have also contained other odd discoveries. The Christian Moerlein Brewery’s Old Jug Lager pottery bottles are a plentiful and amazingly well-preserved local collectible because about five thousand of them were found in brand-new condition in the former bottling building decades after the end of Prohibition; and a room in the basement of the former John Hauck Brewery office is still full of nineteenth-century bottling corks.

Cases of unused crockery bottles of Moerlein’s Old Jug lager were found stored in the depths of the former Christian Moerlein bottling building in new condition almost one hundred years after their production.

Thousands of intervening years, climate changes and shifting sands make it easy to understand how pharaohs’ tombs get lost in the Egyptian desert, but how do you completely lose eleven thousand square feet of building underneath a building, in the heart of an American city, that was used less than one hundred years ago? The answer lies in how a distinct American subculture and one of the city—and nation’s—most important industries were both brought to an abrupt end. The answer is the relatively sudden, unexpected death of a place in time that existed over Cincinnati’s “Rhine.”