A schoolteacher, war hero, lawyer, congressman and former chief justice of New Jersey named John Cleves Symmes extended his lengthy résumé to include surveyor and speculator and purchased a huge tract of land in southwest Ohio. He advertised the land for sale in quarters and sold all of what is now Hamilton County to a fellow New Jerseyan named Mathias Denmann in 1788. The roughly seven to eight hundred acres that became nineteenth-century Cincinnati was purchased for $500. Denmann met up with a Colonel Patterson and a Kentucky schoolteacher named Filson in the town of Maysville (then named Limestone), divided the land up into thirds and hatched a plan to build a city. They teamed up with Symmes and two other surveyors named McMillan and Ludlow and left Maysville on Christmas Eve 1788. The men later disagreed about whether they reached their destination in December 1788 or January 1789, but somewhere in this period of time they disembarked, broke up into two teams and began exploring and surveying their new city—a place that they named Losantiville.

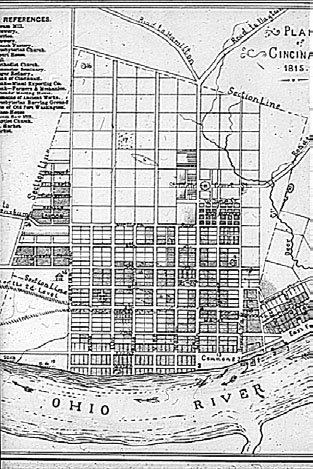

The city was laid out in the Philadelphia method, meaning that it was surveyed and streets were mapped in evenly separated squares with north–south and east–west streets intersecting at ninety-degree angles. While the city’s central business district still retains most of the streets from the original survey, this creates a deceptive image about what the early settlement looked like. The streets existed only on a map. The city was a thick, old-growth forest, and this tidy plan of perpendicular streets began with notches on trees. In fact, one of the earliest families had so much difficulty determining where the street was supposed to be that they accidentally built their house in the middle of it.

Cincinnati was planned using the Philadelphia method, meaning that it was divided into equal-sized blocks and right angles. Streets were laid out in forest and meadows in essentially the same configuration that still exists today in the central business district. From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

Early life in Losantiville was hard. Food was scarce, the forests were dense and the Shawnee tribe had some pretty pointed questions about why a few dozen white people were cutting down trees on their land. The food situation was addressed mostly by fishing. The Indian situation was a little more complicated. Judge Symmes responded to the Shawnee chief’s concerns by showing him a copy of the government documents giving Symmes title to the land. Rather than being pacified by this legalistic approach, the chief fixated on the U.S. government’s seal. From his perspective, the spread wings of the eagle in flight and the bundle of arrows in his talon sent a very clear message: war.

At the end of the Revolutionary War, Congress adopted the position that its treaty with Great Britain concluded both England’s claim to title of American lands as well as that of all the Indian tribes that had fought with Britain against the American colonists. England surrendered the land claims of six Indian nations, including the Miami, Shawnee and Delaware, all tribes inhabiting the areas around Cincinnati; but the English ceded these claims without the knowledge or consent of the Indian nations. From the Native American perspective, the English and colonists had placed them between a rock and a hard place. They faced retribution from the English if they failed to intervene on the side of Great Britain and were considered to have lost their ancestral lands when England lost the war; yet tribes that managed to stay neutral in the Revolution were subsequently slaughtered by American pioneers with equal malice. This made living in Losantiville dangerous. Leaving the clustered settlement to tend farms or hunt often ended in execution. Early municipal law required citizens to take their firearms with them when attending church. The city nevertheless began to grow from its original eleven families and twenty-four single men. In 1790, Losantiville’s population increased by forty families, but growth was marginalized somewhat by twenty citizens being killed in Indian attacks. In 1791, despite new arrivals, the population remained static largely due to the number of people killed fighting Indians. For many years after settlement, the only place safe from Indian attack was within the walls of Losantiville’s Fort Washington, and the city may not have survived without the fort.

Cincinnati’s location on a bend in the Ohio River and the confluence of several smaller waterways is often noted for the strategic decision to make it the site of Fort Washington. However, the real reason for the fort’s location may be attributable to a very nonmilitary strategy. The fort was originally supposed to be located in North Bend, Ohio, a river town that is roughly fifteen miles west of downtown Cincinnati. Major Doughty was sent from Marietta to establish the fort at this strategic location. The arrival of Doughty’s three hundred troops brought a sense of security to North Bend that attracted a handful of settlers. Among them was a man who apparently had a very attractive wife. While on patrol one day, the major spotted the wife and became quite smitten. Major Doughty must have been relatively bold about his desire, because the woman’s husband packed them up and moved to Cincinnati to thwart the major’s indecent intentions. This solution proved far more temporary than Doughty’s lust. Shortly after the husband and wife left for Losantiville, the officer decided that North Bend was completely unfit for a fort and that the budding settlement of Losantiville was far more appropriate, so he packed up three hundred troops to chase after another man’s wife. A nineteenth-century account of the events reflects the randomness of how one man’s adulterous desires changed the fate of Cincinnati:

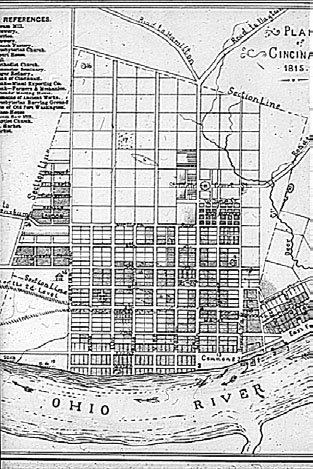

The original city was only a few blocks near the waterfront, with most growth and social life emanating from Fort Washington, located roughly at the corner of Broadway and Third. From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

The beauty of one female settler shifted Ohio’s center of trade from its original cradle to the place where it is now. Had the beauty with her fiery eyes remained in North Bend, then the barracks and fort would have arisen there, North Bend would have become the center of the population, capital of business, and Cincinnati would have been an area of relatively little significance.

Fort Washington came to be erected near the banks of the river in November 1789. (It was located roughly where Fort Washington Way meets I-471, unceremoniously sitting where two parking garages and an interstate highway now reside.) Without the troops, North Bend held little attraction to the few remaining settlers, and the site was completely deserted within three years after their departure. Although North Bend’s panoramic river view eventually led to the settlement of a quaint little town that produced both William Henry Harrison (the ninth U.S. president) and Benjamin Harrison (the twenty-third U.S. president), it never quite recovered from the 1789 amorous departure of its fort. The 2000 U.S. Census reports the population of North Bend as 603 people. Conversely, the location of Fort Washington in Cincinnati helped transform it into the Queen City of the West.

On January 12, 1790, Ohio’s governor St. Clair arrived in Lostantiville to organize the local government. Hamilton County got its name from Alexander Hamilton, then the secretary of the treasury, and the governor changed the name of the city to Cincinnati. The name came from the governor’s association with the Society of the Cincinnati, a fraternal society founded by Revolutionary War officers to “maintain inviolable those noble human rights and freedoms” for which they “fought and spilled their blood.”

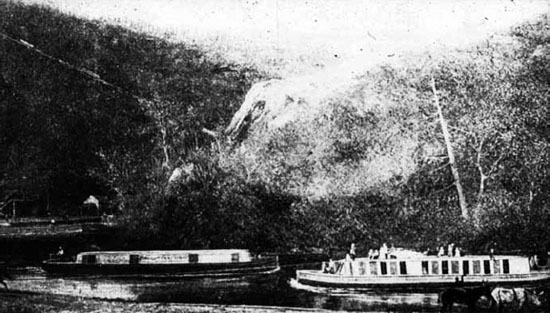

The early city grew largely along the riverfront with steep bluffs behind it, and its economy grew from the river as a trading hub. The city saw its first riverboat traffic in 1811, dramatically increasing the speed with which it could connect to ports as far and as economically important as New Orleans. Construction on the Miami and Erie Canal began in 1825, and the Cincinnati connection was completed in November 1828, with the first boats floating down the route that follows Central Parkway in the spring of 1829. At the time, the area east of the canal on its southern route and north of the area after it took a bend at Plum Street where it roughly cut the downtown basin in half was almost entirely vacant land. There were garden plots and a few streets running north–south (and none running east–west), and the area where Washington Park and Music Hall now sit was home to three cemeteries: the park was home to two, segregated by Presbyterian and Episcopalian; and a “public burying ground” was on the Music Hall lot. This was the countryside, the far edge of town.

The canal connected the Great Lakes to the Ohio River and all the farmland in between. It was the first network for interstate commerce, and the combination of the canalboats and riverboats made Cincinnati the most important city in the western lands, a place that could compete with older, eastern seaboard cities. Cincinnati’s real estate values rose between 20 and 25 percent in the three years following the completion of the canal; and export trade increased from $1 million in 1826 to $4 million in 1832. Nicholas Longworth’s foresight in 1810 to buy thirty acres of what would become the heart of the city helped make him one of the richest men in America by 1830.

The Queen City of the West traded in almost all major commodities of the day, but some staples stood out. Corn was a very common crop grown in the large swaths of farmland served by the canal system, but because it was bulky and plentiful it was also a bad commodity to sell as an export. Instead, farmers either used it to raise pigs or distilled it into whiskey. In 1829, pork was the city’s key export and bacon was the second (apparently distinguishing between livestock and…bacon). Together, the value of pork and bacon exports was $702,796. By comparison, only $182,236 worth of whiskey was exported. This early boon to the economy produced by swine gave the city its “Porkopolis” nickname, but forgetting the importance of whiskey is a bit of revisionist history. Pork was the king of the early Cincinnati economy, but whiskey had a threefold advantage. First, whiskey doesn’t die, get diseased or spoil en route. Second, whiskey doesn’t smell like a pig. And third, it will get you drunk. These advantages helped make whiskey a much larger export than pork in the coming decades. By 1881, the value of all forms of livestock passing through the city was $26,000,000 compared to the $30,972,000 in whiskey exports. A decade later, roughly $9,000,000 more whiskey was being exported than all types of livestock combined, and the export value of whiskey and beer together had reached $39,300,000.

Canal traffic through Cincinnati began in 1828. From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

The explosion of trade and growth of the city also drew newcomers and created a rapidly changing face of the city. A German family was among one of the first eleven families to settle in Cincinnati and German-American major David Ziegler was elected the city’s first mayor in 1802, but Germans were a minority in early Cincinnati. In fact, some historians have attributed Major Ziegler’s election, in part, to a sympathetic public reaction to his ethnic-related mistreatment in the army. Ziegler resigned from the army while serving as the commander of Fort Washington due to charges of insubordination and “drunkenness,” an early taste of conflicting social mores about alcohol consumption. Most of Cincinnati’s early settlers were native born, coming from New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York. This remained the case for some time. By 1825, 80 percent of the population was still American-born, and people from England, Scotland and Wales constituted a clear majority of foreign-born. That changed as German and Irish immigrants started arriving in significant numbers in the 1830s and 1840s.

In May 1832, tens of thousands of would-be revolutionaries of all walks of life met at Hambach Castle in Rhineland-Palatinate (now one of the sixteen states in Germany) to listen to speeches about liberty and civil rights. Apparently more like Woodstock than storming the Bastille, no cohesive action arose from the festival. In fact, the primary result was a further crackdown on civil liberties and persecution of attendees. This drove many to leave and seek freedom in America. Most of these immigrants were leaving for both political and economic reasons, but enough were well-educated and skilled craftsmen that they became successful professionals, artisans and tradesmen in their new homeland. Its growth and importance on the western frontier made Cincinnati a logical place to come, and immigrants arriving in the 1830s and ’40s started changing the face of the city—both its ethnic makeup as well as its physical development. The earliest German immigrants to arrive in the city mixed with the rest of the population along the river and the central business district, but this wave of immigrants known as the “Thirtyers” started to settle in the previously vacant lands north of the canal.

By 1840, immigrants were still living in different areas throughout the small city, but clear development and housing patterns were starting to emerge. In 1842, a large area of field and scrub brush north of the canal and east of Sycamore Street that Cincinnatians called “Texas” was sold off as developable parcels of land, giving birth to the area known as Pendleton. This area, along with the territory between Sycamore and the eastern border of the canal, became primarily and increasingly home to new German immigrants. The area developed such a heavily German-dominated presence that the canal was nicknamed the “Rhine.” Going over the canal into the German section was said to be going “over the Rhine,” giving a name to the neighborhood that was growing so rapidly that contemporary observers said that streets and homes seemed to spring up almost overnight.

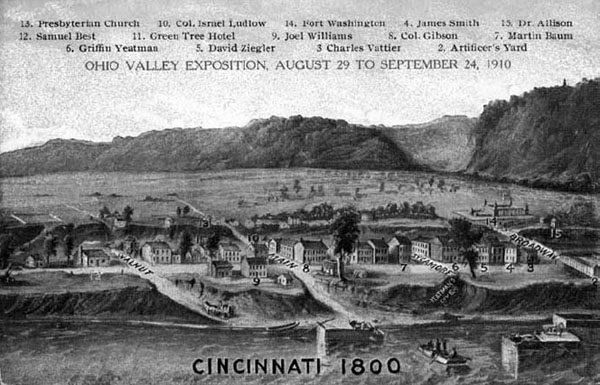

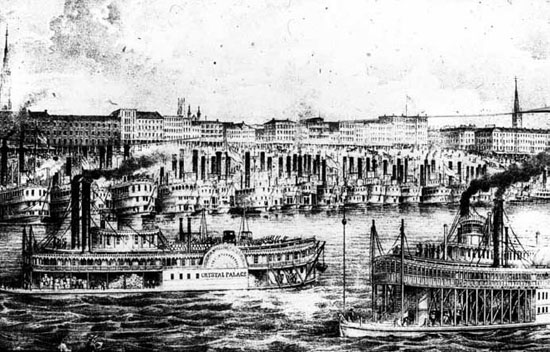

The first steamboat traffic began in 1811. By the time this sketch was made in 1833, Cincinnati was becoming “the Queen City of the West,” the hub of commerce west of the Appalachian Mountains. From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

In 1848, a more serious revolutionary wave swept the German states and briefly threatened to establish national unity and democratic government. However, this attempt at revolution was also doomed for being more idealistic than strategic. Ground gained was quickly lost to overwhelming military strength. Authoritarian rule, execution of revolutionaries and mass exodus followed. The refugees who fled for political reasons became known as the “Forty-Eighters.” It is unknown how many “Forty-Eighters” came to the United States because they arrived over a period of years in the late 1840s and ’50s and because it is impossible to decipher political refugees from immigrants motivated purely by economic reasons, but the total number arriving in the United States is estimated between four and ten thousand. While there were few Forty-Eighters in overall numbers, they were influential leaders in the communities where they settled, including Over-the-Rhine.

These early waves of German immigrants helped bring more German immigrants. Letters home and accounts of American success in German publications brought friends, family and fellow countrymen. Strong early leadership in the German-American community and the German-heavy population of Over-the-Rhine made it a comfortable place for a new arrival, a community where it was unnecessary to speak English to find a job and conduct all the aspects of everyday life. Cincinnati was also a land of opportunity. Immigrants arriving in the 1850s and 1860s found a rapidly growing city with seemingly endless opportunities, many of them offered by the fellow German-Americans who preceded them. Although encouraged to learn English and the customs and traditions of their new country, German-Americans were also encouraged to retain their sense of independent identity. They waded into Americanism by reading tips from German-language papers and learning about the city through socialization in Over-the-Rhine saloons and through membership in German societies.

The city became home to a large number of the more than half a million Germans who flooded American shores just between 1852 and 1854 and the millions more who came in the following decades. New arrivals found more than a growing city with people who spoke their language. They found old world Gemütlichkeit (roughly translated as festive hospitality). The Germans were said to have brought the notion to America that it is a good thing to have a good time, and this spirit quickly began to permeate in the area of Cincinnati over the Rhine. Nationally and within Cincinnati, this was changing mores. When the first boats floated down the Miami and Erie Canal, drinking had become rare among the respectable middle class, and intoxication was scandalous. Two decades later, this had changed. In 1856, the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce declared lager beer “a fashionable drink,” and a few years later it observed that “Cincinnati had acquired the taste for ‘Lager,’ as a beverage, not only among the native German population, but all classes.” The “Beer Gardens where this beverage is swallowed by old and young and in incredible quantities [had] become institutions of great magnitude.” By the end of the Civil War, Over-the-Rhine’s beer gardens were increasingly filled with the native born of all classes. Even devout Christians started to view total abstinence as old-fashioned. Lager beer became the drink of choice for young adults. It became so popular, in fact, that there was a decrease in per capita consumption of hard liquor even though per capita drinking remained steady. (Liquor consumption dropped 20 percent, and lager beer consumption increased 74 percent.) To the chagrin of temperance advocates, much of the middle-class stigma against drinking had disappeared and a much broader slice of America was enjoying a cold beer—but not everybody. In the mid-nineteenth century, the nation had become clearly divided between drinkers and abstainers. The division largely followed ethnic, religious and class lines, and it started to play an increasingly dominant role in politics.