In the 1875 tome History of the Great Temperance Reforms, Reverend James Shaw uses the “science” of the day to conclude that “[a]bout ninety per cent of the suffering, pauperism and crime in Europe and America come from intemperance.” He blamed alcohol for the destruction of families: “The drunkard’s children are left often without food, clothes, care or support, grow up as tender plants of disease, wretchedness, poverty and disorder.” He blamed it for nations losing military battles, arguing that drunken sailors sink ships. He blamed it for mental illness: “[T]he drunkard not only injures and enfeebles his own nervous system, but entails mental disease upon his family. His daughters are nervous and hysterical, his sons are weak, wayward and eccentric, and sink insane under the pressure of excitement.” He blamed it for taxation and the increased need for social services: “As intemperance inevitably leads to poverty, so poverty must end in Pauperism.” He blamed it for dumbing down society: “The habits of the parents of three-hundred of the idiots were learned, and one-hundred-and-forty-five, or nearly one-half, are reported as known to be habitual drunkards. The parents of cases sixty-two were drunkards and had seven idiotic children.” He even blamed it for cholera, noting that a Glasgow doctor claimed that in a recent cholera outbreak only 19 percent of temperate patience died, compared to 91.2 percent of drinkers. And, of course, he blamed alcohol for almost all crime: alcohol “prepares the way for the commission of crime of every kind, and for those which require a steady hand and a clear head, there is need of the paralyzing effect of the alcohol upon the conscience and moral sense, and that such an effect is desired and sought by the professional criminal is a fact well known…Enraged tigers and hideous vipers could roam our streets more safely than human beings so poisoned and crazed by strong drink.”

While Shaw and fellow temperance crusaders oversimplified complicated social factors and often confused correlation with causation, they were responding to dramatic and undeniable changes in society. People drank in early America. In fact, by 1830, the average American male was consuming more than four times the amount of liquor consumed today, mostly in the form of whiskey or hard cider. Alcohol was considered healthy, “particularly for digestive ills.” Parents put sugar in it to make it sweet for sick children. In early Cincinnati, many people drank nothing but alcoholic beverages. Coffee and tea were luxury items, and milk and water were often diseased. As Cincinnati entered the 1840s, it was not the amount of alcohol that people drank that changed. What changed was who drank it and how they drank it.

Between 1800 and 1860, the number of cities in America with more than ten thousand inhabitants grew from six to ninety-three. During the mid-nineteenth century, America went from an agrarian nation to one more heavily dominated by a new form of urban life. This brought dramatic changes in family and social structures. In earlier agrarian America, people lived and worked on the same plot of land, with their families. Most of the population only traveled to town periodically and for necessary reasons. They might come into contact with the occasional Swede or German, but they were primarily Anglo-Saxon Protestant. Men commonly drank alcohol, but they did it during the workday and in family settings. Public intoxication was a rare site, and so was crime.

Significant immigration occurred from Germany and Ireland during the period when Cincinnati was the most important city in the western lands. Cincinnati was transformed in a relatively short period of time, and it lacked precedence or infrastructure for handling it. Cincinnati’s saloon-to-resident ratio remained both high and relatively constant throughout the nineteenth century. In 1834, it had approximately 223 saloons and taverns, or roughly one for every thirty-eight males over the age of fifteen. In 1890, the number of saloons had grown to 1,810 but the population was 297,000, meaning about one saloon for every forty-one adult males. However, the face of drinking changed. Early drinking establishments were taverns. These places typically served food and had lodging for travelers. Saloons, also commonly called “dram-shops,” “ale houses,” “porter houses” or “coffee houses,” were different from taverns. They were purely urban institutions, catering to the urban working class. Saloons added the bar to bars—a place where you could stand and have a drink (or several) by the glass.

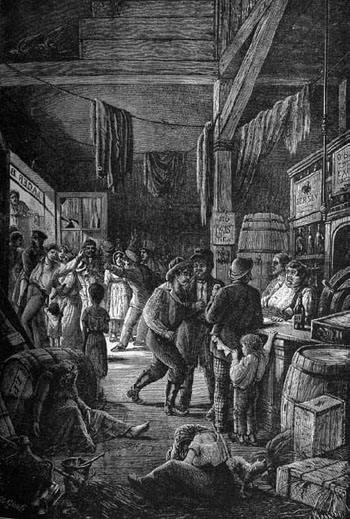

Temperance publications depicted all saloons as houses of vice and debauchery, portraying neglected children, ruined women and violence. From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

A depiction of life inside Wielert’s, where women and children were welcome and safe, with the symphony playing in the background. Courtesy of Steven Hampton, president, Brewery District CURC.

As waves of immigrants arrived in the city to seek industrial labor positions, Cincinnati saloons became increasingly associated with the city’s German and Irish populations. Temperance had always had ethnic, religious and socioeconomic biases. The ethnic and religious biases remained fairly constant, but there was some shift in the socioeconomic makeup. Early temperance movements were characterized by the affluent attempting to impose moderation on the unruly working class, but by the mid-1800s, the face of temperance had become solidly middle class. What remained constant was its white Anglo-Saxon, usually native-born makeup. The movement also tended to glorify rural life and demonize cities. The connection between immigrant groups, new patterns of drinking and some legitimate complaints about city life led many to agree with local and notable temperance advocate Samuel Carry when he called Germans the “disorganizers of society.”

Protest against alcohol use and immigration cannot be dismissed in the 1800s as purely xenophobic or puritanical. There were legitimate social problems associated with both immigration and drinking, and they often went together. In 1819, Cincinnati’s combined German and Irish population had been 10 percent. By 1840, it had risen to 34 percent after an explosion of the population. Although the Irish waterfront was far more impoverished, dirty and violent than the German neighborhoods, Over-the-Rhine rapidly accumulated its own populations of unskilled immigrants in increasing congestion, and many native Cincinnatians painted all immigrants with the same brush. In the later half of the nineteenth century, new arrivals were increasingly unskilled and impoverished. This forced increases in city welfare spending. Immigrants also violated general customs and liquor laws, most notably drinking openly on Sundays. This was the case since at least the 1830s, but it became a bigger bugaboo among the puritanical set as greater numbers of immigrants and a growing acceptability of public drinking made it more visible after the Civil War. Saloons were also a matter of contention. While the vast majority of saloons throughout the city seem to have been congenial, social places, many did maintain prostitutes, and some in places like Irish “Rat Town” were likely the common scenes of extraordinary violence. Regardless of their orderliness, it had to constantly rub temperance advocates the wrong way as they walked through areas like Over-the-Rhine where there was a saloon every few feet.

Most complaints against the immigrant populations combined a basis in fact with irrational conclusions. After Cincinnati German singing societies held a singing festival in 1849, a subsequent cholera epidemic was blamed on the Germans. Nineteenth-century German historian Emil Klauprecht observed that this was “an opinion accepted by a lot of bigots.” No matter how off-key, German singing does not give people cholera. However, crowded tenement housing with inadequate access to fresh water does contribute to both the outbreak and spread of disease. While the worst living conditions were reserved for the Irish and African Americans, living conditions would have gotten progressively worse in Over-the-Rhine as the open fields and freshwater canal of 1830 became one of the nation’s most densely populated neighborhoods—bordered by an open sewer. Crime increased dramatically in the mid- to late 1800s, and immigrants did begin to constitute a higher percentage of offenders. In 1845, there were only 873 arrests in all of Hamilton County. In 1853, there were 6,769 arrests just within Cincinnati’s borders; and as crime rose, so did the percentage of immigrants being arrested. In 1845, immigrants constituted 28 percent of Hamilton County’s jail population. The percentage rose to 54 percent in three years and hit 65 percent in 1863. Some of this was attributable to changes in policing, but most reflected an actual rise in criminal behavior.

Any criminal behavior that fed the stereotype of drunken, violent immigrants was a feather in the hat of temperance and prohibition advocates. In 1884, they were handed an ostrich feather. Crime was big headlines in Cincinnati. Murder, rape and robbery seemed commonplace. In part, this was attributable to reasons that sound familiar today. Cincinnati had close to a dozen English- and German-language newspapers in the 1880s that all had to compete with one another for audiences. Papers had already learned the adage “if it bleeds it leads” and routinely reported on grisly crimes regardless of where they occurred. This exacerbated accurate perception in Cincinnati that the criminal justice system was terminally flawed. The city only had a few dozen police officers, many of whom future Governor Foraker would describe as having “a bad reputation” because “[a]mong them were some who had been convicted of crimes, and others who…were charged not only with connivance at crime but with the actual commission of crime while on duty.” Cincinnati cops were known to rob people at gunpoint while wearing their uniforms. Trials took unnecessarily long periods to occur after indictment, often long enough that witnesses disappeared or failed to recollect events. Charges were often dropped by judges without findings of fact or legitimate cause. Juries simply failed to convict obviously guilty people, and when convictions occurred, sentences were often remarkably light. Charges of corruption, bribery and incompetence ran rampant. All the while, the papers continued to churn out stories of grisly crimes, and they did not always have to go far from home to get them. In one particularly heinous example in 1883, an Avondale family was butchered so that the killer could sell their corpses to a medical college for dissection. Killing people for salable product to medical colleges or using dissection as a means of getting rid of the bodies of murder victims was either so common, or at least believed to be so common, that state law prohibited medical colleges from accepting bodies that showed marks of violence without notifying the coroner.

At a time when the public was outraged at crime run amok, a senseless murder was committed on Christmas Eve 1883. Two stable hands, William Berner, described as “a young German,” and Joseph Palmer, “a light mulatto,” murdered their employer, William Kirk. Mr. Kirk was savagely beaten and strangled to death. His body was tossed into the back of a wagon, taken to the outskirts of town and dumped in a thicket of bushes. The motive was $285 that Kirk had earned on the sale of a horse. After apprehension, the killers demonstrated no signs of remorse. Berner confessed no less than seven times and admitted that the plan had been hatched weeks in advance. The crime was a clear example of first-degree murder, a capital offense—a hanging offense—but Cincinnatians had good reason to believe that justice would be denied.

The system didn’t seem to be working, and there was immediate public speculation in the Berner case about the relationship between the defense attorney and his former law partner, the presiding judge. All of the speculation surrounding the trial was heightened when Berner’s attorney had the trial bifurcated, meaning that Berner and Palmer would be tried separately. Berner was going to be tried first. To many, the writing on the wall was clear: the young German would be acquitted and the black guy would hang for the crime of both men. No one seems to have been bothered by the fact that Palmer was likely to hang, but the public turned pretrial speculation into irrefutable proof that the justice system was inept and corrupt. This sentiment had merit. A total of 504 men were called in jury selection in order to adequately handpick a jury of 12. Jury selection had been dragged on so long that it was said to have cost the state $5,000, and Berner’s father reportedly paid the defense attorney $4,500, a legal fee that drew outrage in 1884.

As the trial got underway, it became a primary topic in beer gardens and saloons. Saloon windows displayed caricatures of the jury and the attorneys with derogatory and violent captions. Rumors of bribery, collusion between the attorneys and judge and jury tampering ran rampant. Booze and trial news were being blended in an increasingly combustible cocktail.

Rather than capital murder, Berner was convicted of mere manslaughter on March 27, 1884. The jurors left the courthouse marked men. One of the jurors was badly “beaten by a number of his acquaintances,” and a juror from Harrison fled his home. Another juror was fired from his job, and his co-workers spent the lunch hour hanging his effigy. The jury foreman went into hiding. A public meeting was called at Central Turner Hall that evening, and a larger public meeting was planned for the following day, the day of sentencing. At roughly 2:00 p.m. on Friday, March 28, 1884, Berner was sentenced to twenty years in prison for the confessed brutal, capital murder.

Organized primarily by affluent and respected Cincinnati citizens, an open meeting was held at Music Hall later that evening. The planned speeches mostly addressed the need for judicial reform: different rules for jury selection, methods for processing criminal cases faster and higher ethical standards for lawyers and judges. The large audience was polite during the speeches and the meeting was orderly, but violence was the clear undertone. “Ropes suitable for a lynching party were openly displayed and threats of mob violence were frequently heard.” The meeting concluded mildly with a resolution for legal reforms, but as soon as the crowd of between six and eight thousand frustrated citizens made their way out to Elm Street, a loud call arose: “To the jail!”

Some people carried lynching ropes, some acquired stones or other weapons, some just went along out of curiosity about what was going to happen. There was no clear leadership, just thousands of agitated citizens making their way from Over-the-Rhine to the county jail, built immediately adjacent to the courthouse (both essentially located where the courthouse and Justice Center are today). The group accumulated more curious marchers as it proceeded. At the time a crowd of thousands reached the jail, it was staffed only by the sheriff and a handful of deputies. Joists, crowbars and hammers were used to gain entry into the jail office through an iron basement door. Fearing that a violent response to the crowd would make the situation worse, the sheriff had ordered his men not to fire on the crowd. This permitted them to continue to pry through the interior iron doors separating the office from the spiral stone stairwell up to the cells. Members of the mob made their way freely through the jail, demanding that prisoners tell them where Berner and Palmer could be found.

Fortunately for Berner, he had already been taken from the jail to be put on a train to the state prison in Columbus. This protected him from the Cincinnati lynch mob, but he almost fell into the hands of one in Loveland. Stopped awaiting documents and a transfer, an angry mob tried to take Berner from police custody for summary justice, but the crowd mistook one of the deputies for Berner, jumped him and started beating him severely. This provided Berner with the opportunity to escape. While the streets of Cincinnati were already stained with blood, Berner was “coolly enjoying a game of cards…unaware of the riot” when he was reapprehended by Cincinnati detectives and a Loveland marshal on the following Saturday afternoon. The mob in Cincinnati was ignorant of both Berner’s transfer and his escape. The sheriff advised the crowd that he had been transported, but his words were interpreted as a ploy to drive the crowd away.

Palmer, on the other hand, remained in the jail, vulnerable to mob lynching. He seems to have survived the night due largely to his own steely, sociopathic nerve. Apparently a very light-skinned man, when the mob approached his cell and demanded that he verify his identity as the accused Palmer, he responded: “No, can’t you see that I am a white man?” The calm of his reply under the circumstances was sufficient to cause the group to pass on to other cells. None of the prisoners was harmed during the time that the crowd was roaming through the jail. There were twenty-three murder suspects incarcerated at the time, including the alleged murderer of the Avondale family. Reports vary about whether the intentions of the crowd included lynching all of them or just Berner. Since there was no leadership, it is likely that the intentions and purpose of the group varied by individual.

Fifteen city police officers arrived as backup but were pushed out of the way by the crowd. A little before 10:00 p.m., the riot alarm was sounded. This brought more police backup and the local militia, but it also had the effect of drawing more members of the mob—a group that may have reached as many as ten thousand people. When the mob made its way back into the jail, the militia shot a volley of blank cartridges in hopes of scattering the rioters. The riot alarm also led to the evening’s first casualties. Additional police officers made their way through the crowds and into the jail by entering the courthouse on Main Street and coming through the underground tunnel that connected the buildings. The policemen shouted out who they were as they came through the tunnel, but edgy and now using live ammunition, militiamen shot at least five of their brethren. The militia later blamed the shootings on rioters, but officers who lived through it confirmed that the militia fired the shots.

Still believing that Berner was inside, the mob tried to burn the jail by lighting adjacent wood buildings on fire, trying to force the evacuation of the jail, and made continued attempts to regain entry. Friday night’s fires were ultimately extinguished. Unaware that the sheriff had ordered his men to refrain from firing on the crowd, or that the militia was initially using blanks, the mob looted gun stores and hardware stores, stripping them of rifles, powder and ammunition. A cannon was taken from the city’s largest gun store and paraded down Main Street by a group of about fifty people, led by fife and drum. Rioters busted out the jail’s windows with rocks and started firing pistols into it. Police and militia started firing back. The sheriff gave orders to shoot above the crowd to try to disperse them. The sheriff seems to have remained a steady voice of discipline and restraint, but he had limited control in a confusing chain of command that helped exacerbate the situation. The sheriff only controlled the jail building and his deputies. County commissioners claimed jurisdiction over the courthouse building. The chief of police, who was also present, gave orders to his men that could contradict the ones that Colonel Hunt gave the militia or that the sheriff gave his deputies. During most of the riot, the mayor was too ill to get out of bed. The militia ignored the sheriff’s instructions and started firing directly into the crowd. At roughly 1:30 a.m., a seventeen-year-old laborer named Lew Kent fell dead in the street, shot through the brain by a militiaman’s bullet. He was the first murdered civilian but far from the last. At a little after 2:00 a.m., a man named Newton Cobb from Manchester, Ohio, was shot in the shoulder by soldiers firing from inside the jail. He may have been the first casualty described as a “bystander,” but by 2:30 a.m. two more people described as “bystanders” were seriously shot, and three more lay dying of bullet wounds. Militia justified firing indiscriminately on people in the street by claiming that they were trying to prevent the jail from being burned or blown up by groups that were pushing drums of coal oil into the entryway. As the crowd started to thin out around 3:00 a.m., the militia emerged from the jail and started firing at people who were running away. Police then roamed the streets in armed patrols for the remainder of the early morning hours. Using overturned carriages, furniture, sandbags and whatever was available, barricades were hastily erected around the jail in all directions. Another war had erupted on the banks of Cincinnati’s Rhine.

On Friday, a mob wanted to lynch two murderers. As nefarious as this motivation may have been, at least it was consistent with a protest over rampant crime, political corruption and lax law enforcement. The motives were different on Saturday, less defined and dramatically more ironic. On Saturday, the motive was revenge. The crowds wanted to make the militia and law enforcement pay for the blood spilled during their sloppy attempts to maintain law and order on the previous night.

A large crowd started to form early on Saturday. “All day long Saturday, the militia and police were on duty, and the court-house and jail were surrounded by tired-out but determined men.” No blood was shed during daylight hours, but crowds built throughout the day. The crowds grew larger and more aggressive as dusk gave way to the darkness of a new moon and Saturday night began. A witness noted that “[t]he mob is greater than last night and there are more drunken men in it.” By nightfall, the jail and courthouse were surrounded by a sea of people stretching blocks in every direction. As motives became more amorphous and newspapers were reporting Berner’s escape from custody in Loveland, what building was attacked may have become less relevant. More importantly, all three sides of the jail had been heavily barricaded, but no barricades had been erected in front of the adjacent courthouse. At roughly 9:00 p.m., “[t]he riot began with the throwing of boulders and brick-bats at the Court-house, while some fired pistols and shot-guns at the windows.” The crowd battered down the iron front door of the building. As one group was attacking the door, another entered the treasurer’s office, located on the northwest corner of the building, by breaking into a basement window. This group broke up furniture, covered it in coal oil and set the courthouse on fire. The courthouse and jail were only connected by the underground tunnel, and there was a yard between them, so burning the courthouse seems to have had no motive beyond general destruction. Among a wealth of other articles of public interest, the building was said to have contained one of the most extensive and historic law libraries in the United States. As the courthouse slowly burned, rioters began shooting at the militia and policemen who made attempts to douse the fire. The police and militia shot back. Death started to accumulate. Periodically, someone from the crowd would wave a white flag, move from haphazard safety positions in doorways or behind buildings or barricades and drag the dead or dying off the battlefields of Main, Court and Sycamore Streets.

Earlier in the day, as violence appeared eminent, the governor called out National Guard regiments from across Ohio. The Fourth Regiment from Dayton was the first to arrive a little after 9:00 p.m., but when they glimpsed the extent of the brutal, senseless bloodshed, they turned around, walked back to the train station and returned to Dayton. Regiments from Springfield and Columbus were more useful. Arriving about 10:00 p.m. on Saturday, they drove the crowd farther from the courthouse. This gave the fire department the space necessary to save the northwest corner of the building, which contained some of the public records. Out-of-town militia also stepped up the violence. Their arrival led to “men being mowed down like grass under the keen sweep of a scythe.” The police department’s Gatling gun was brought out to hold the line, but its only role on Saturday was intimidation. There may have been consternation by law enforcement about using a weapon that could fire a constant rain of bullets on a crowd of fellow citizens, but restraint with the Gatling gun did not stop the growing number of casualties. Initially, Saturday’s dead were taken to a nearby restaurant. When its tables were filled with the dead, dying and seriously wounded, casualties were taken to Burdsal’s drugstore on Main Street. When it had accumulated its maximum number of bodies, a saloon on Ninth Street became the temporary morgue. By midnight on Saturday, a witness noted: “Such a night of blood as this has not before darkened the history of Cincinnati.” The areas around Court and Canal were a literal war zone, with seemingly countless Cincinnatians willing to sacrifice their lives for no clear or rational purpose. A journalist wrote that for “some unaccountable motive the mob stands in the streets in range of soldiers’ guns, apparently courting death.” Kinzbach’s drugstore, at the corner of Court and Walnut, became the next business converted into a morgue when the other locations could hold no more bodies.

Groups of men went searching for weapons. A crowd moved through the night down Main Street. Their target was William & Powell & Co.’s gun store. They brought barrels of coal oil that they intended to use to burn through the storefront. This plan was thwarted by the owner and his clerks. They were hiding inside the gun store—well armed. Five rioters were shot, and the rest retreated. Another group took two cannons from Music Hall, but police recaptured the guns while the rioters were still trying to find powder to fire them.

Sunday was a day of apprehension. It was rumored that city hall and Music Hall would both be the targets of mob violence. Police and militia camped out in city hall in preparation for a standoff. Nationwide, people watched bulletin boards and news wires for updates on the fate of Cincinnati. City streets within firing range of the courthouse were deserted. Barricades had been added on Main and Court Streets on the courthouse side. Sunday’s violence reached murder pitch faster than the day before when a man was shot by militia in Over-the-Rhine, probably from behind the newly erected barricades on the Main Street bridge. This was the first daylight shooting. Most of the day was spent by groups tossing stones at the police and militia and shouting insults. One of the taunts was reportedly, “Wait till to-night! Wait till to-night! Wait till we get good and drunk and we’ll hoist you blue coated men behind your barrels!” The Gatling gun was put into actual service for the first time. By roughly 8:00 p.m., gunfire had begun at the courthouse, described as “heavier than at anytime last night.” Just trying to cross the street blocks away from the courthouse, one of the city’s wealthiest pork barons was caught by a bullet from the Gatling gun at the corner of Ninth and Main.

In a scene that must have been reminiscent of the 1855 election riots, militiamen and city police man a barricade at the Main Street bridge over the canal. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society Library, Cincinnati Museum Center.

There were also signs that mayhem was spreading. A man had been murdered on Fountain Square on Saturday afternoon. A group broke into Music Hall to try to take cannons and was driven off by militia. A group of men or boys was shoving streetcars off the track. Another group went to lynch one of the Berner jurors but abandoned the plan when he wasn’t at home.

Hundreds more militiamen were coming in from all over the state of Ohio. Cincinnati businesses were closed. The typical revelry of a Sunday afternoon was replaced with quiet streets. Beer gardens and saloons were shuttered. After the first use of the Gatling gun at 8:00 p.m., it was fired periodically at random down the street to keep the streets clear and prevent the accumulation of rioters. It worked. There were now between 2,500 and 3,000 militiamen guarding the courthouse, and the federal government had issued the approval to dispatch federal troops. The governor then gave the order for any and all remaining guardsmen not already in Cincinnati to go there with haste. Rumors of continued violence, conspiracies, plans for organized attacks and forces being marshaled in Kentucky or Turner Hall were rampant, but none transpired into action. Three days of rioting were concluded with an overwhelming show of force. Initially, there was fear that violence would re-erupt as soon as troops were withdrawn, but that did not occur. Monday, March 31, was quiet all day and evening.

Peace was restored, but nothing was solved. At least 45 people had been killed, and a known 123 were injured. Actual injuries were estimated to be in the hundreds, with only the most serious cases seeking help. Some changes to the criminal justice system followed the riots, but they were modest. Significant changes in police qualifications, training and ethics were implemented. A renewed sense of law and order was said to have fallen over the city and the use of capital punishment increased, but the riots and looting also attracted a number of criminals from other cities. This apparently attributed to a notable rise in crime following the riots.

William Berner was a model prisoner who accumulated “good time gained” and was released from custody on June 5, 1895. He would have been roughly twenty-nine years old upon his release. Berner’s defense attorney was charged with “bribery and subordination” for his role in the trial but was acquitted.

While no one seems to have bothered arguing that the riots solved anything, a great deal of time and effort was spent looking for who and what to blame for their occurrence. The press was blamed, and they deserved it. Before the riots, the Cincinnati Enquirer had suggested “that the temporary elevation of Judge Lynch to the bench seemed necessary and therefore justifiable.” Lawyers were also blamed with both justification and overstatement. Although not absolute, there were ethnic and socioeconomic differences in opinion about the militia. The German-language press placed primary blame on the militia for causing Saturday’s and Sunday’s violence by indiscriminately firing on the crowd who were unarmed on Friday night. Some English-language commentators took the opposite tack, concluding that no one in the Friday night crowd was truly innocent and suggesting that the sheriff should have immediately called out the Gatling gun and established order with merciless, murderous force

Of all the hindsight dissection, the most extensive was a book-length, rambling, preaching diatribe called The Cincinnati Riot: Its Causes and Results, published in 1886. In it, author J.S. Tunison goes through a number of these causes and observations and adds extensive criticism of the political process and machine politics but ultimately places most of the blame on one culprit above all others: beer.

It was said on Saturday that “excitement in the city grew hourly, especially in that part of the city over the canal.” People feared that Saturday would be particularly bloody because it was payday and Sunday was a day off of work for many—the recipe for drunken disorder. Observers noted that more people appeared noticeably intoxicated on Saturday evening, and it was clearly the bloodiest, most destructive and baffling low point in three days of carnage. Although stolen just like weapons from the armory and private gun stores, forty of the rifles used by rioters were procured from Central Turner Hall. Unlike any other source of stolen guns, this (at least temporarily) led to a rumor that the Turners were entering the riot as an organized force. It did not go unnoticed that although the list of names of the rioters killed and wounded include some Anglo-Saxon surnames, a smattering of O’Day, Sullivan and McHugh and several described as “colored,” a disproportionate amount of the casualties had names like Breitenbach, Westenhoff and Vogelgesang. If the fallen are a representative sample of the crowd, German-American laborers composed most of it, particularly on Saturday night; and among the very few victims with professional qualifications were two brewers.

Like the May 4, 1886 Haymarket affair in Chicago, there seems to have been some discussion in Cincinnati about the notion of a “blood disease,” the idea that some ethnic groups—like Germans—were less capable of functioning in democracies and were prone to anarchy. The Cincinnati Riot took a more nuanced and paternalistic tone. While Tunison concluded that Cincinnati’s German-American community was responsible for “demoralizing the youth of other nationalities” and making “vice rampant and unblushing,” his solution was not specifically anti-German. In Tunison’s view, Cincinnati had good, productive German-Americans. The fact that the rioters were primarily German did not reflect badly on what Tunison called “the better classes of German people.”

The solution was not to root out the immigrants but to root out the forces that corrupted them: “People are ruled more than they would be willing to confess by example, and what Cincinnati needs now, and for years to come, will be an example of conservatism in social affairs, in politics, in art and in morals.” Specifically, Cincinnati showed a lack of religious observation. This was particularly apparent in the amount of drinking that occurred on Sundays, and seemingly above all else, Tunison blamed the riots on lax enforcement of Sunday liquor laws:

Through its history, the city has shown a remarkable respect for all laws except the so-called Sunday liquor laws. The experiment made with these have shown that such legislation, so far as one city in the United States is concerned, is worse than useless, because, by producing laws which cannot be enforced, it tends to bring all law into contempt…The morality of the whole city has been so vitiated by the German proletarian view of things, that the people as a whole have nothing to do with the conduct of the individual, that, in short, freedom in a free country means the license to be as wicked, as injurious to society, as disgusting in personal habits as the most immoral and reckless persons may choose to be. If that is freedom in a free country, commend us to a despotism where such human beings as these have to be vaccinated, whether they are willing or not.

Tunison also blamed machine politics, but he blamed machine politics on working-class Germans: “It is useless to deny or conceal the fact that Cincinnati is at the mercy of a proletariat hardly less vicious than that which controls New York. The difference is that the proletariat in one case is Celtic in the other Teutonic.” Ironically, the city’s reaction to a genuinely, clearly corrupt Democratic city government gave rise to the most notorious era of machine politics under Republican Party “Boss” Cox.

The courthouse riot in 1884 was one of the bloodiest and most senseless urban riots in the nation’s history. It represented the culmination of decades of disorder and social decay, and Tunison spoke for many when he laid the blame for all the havoc on drunkenness. At a time when the city contained about two thousand saloons, breweries were producing previously unimaginable amounts of beer, brewing had become one of the city’s most important industries, whiskey was one of the biggest exports and the seven-day-a-week revelry in Over-the-Rhine seemed nonstop, it was a mistake to conclude that prohibition forces were down for the count. Rather, they were building up ammunition.