10

AS BAD AS IT GETS

JONES ENTERED THE First Infantry Division, brigade headquarters tent, and asked to speak with the commanding officer. Three days before, Lieutenant Jones had briefed him about the impending mission they were to launch from his base camp across the border into Cambodia.

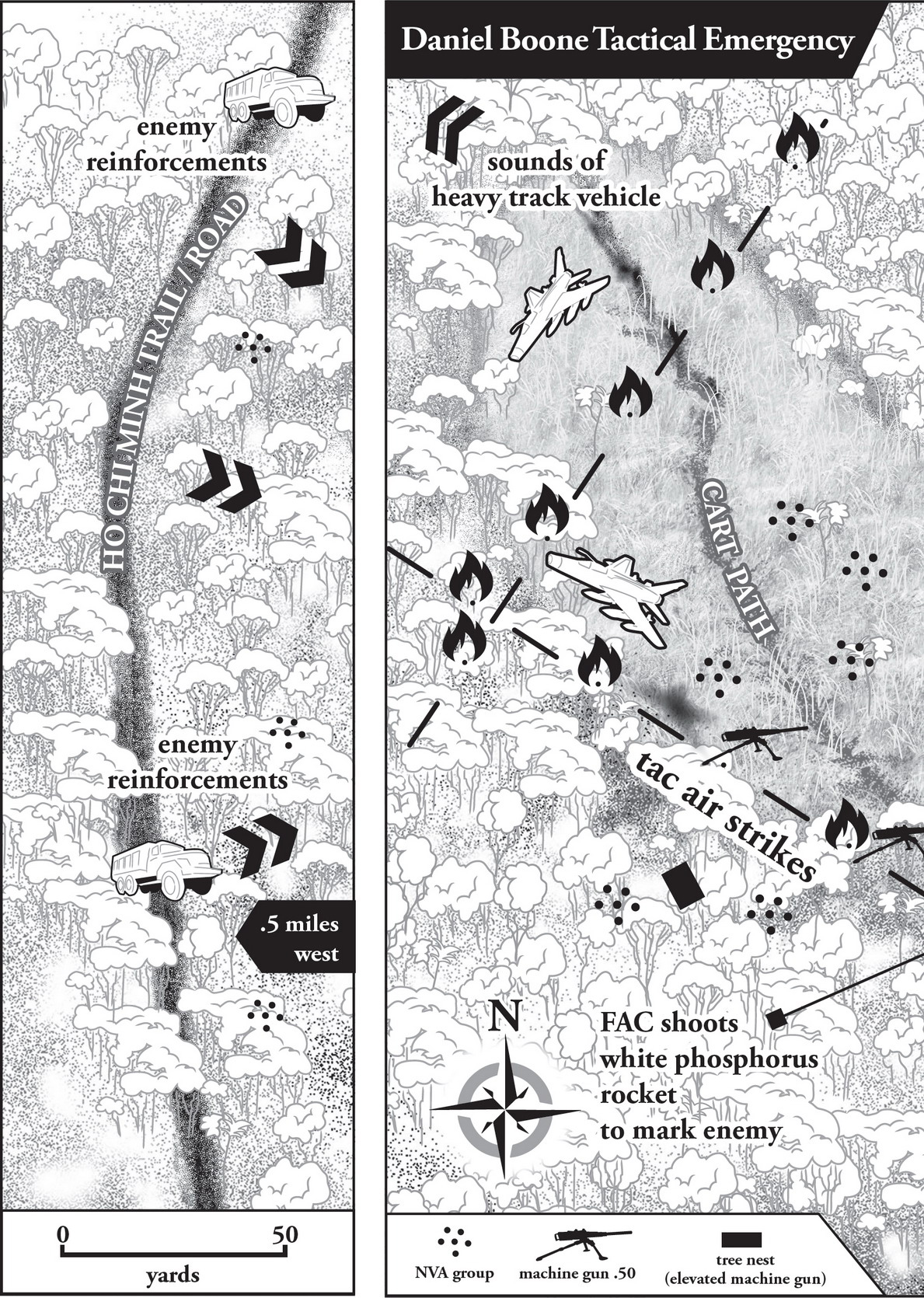

Much of the B-56 recon missions had, in the early months of 1968, been focused within South Vietnam and on the infiltration routes along the Cambodian border. The May 2 mission was the deepest B-56 had probed into Cambodia; the strategy, according to Jones, was to fly over the enemy that was massed and entrenched along the border and insert the men where they were not expected.

Now Jones found the colonel in his office, along with his S-2 (intelligence) officer, a First Infantry Division major, up to their elbows planning San Diego (search-and-destroy) missions. They looked up from the map they were studying.

Anticipating that the team on the ground was about to get into trouble, Jones said to the colonel, “Sir, we have a Daniel Boone Emergency.”

“He looked at me like I had three heads,” says Jones. “He had no idea what I was talking about.”

“Sir,” the S-2 officer interjected, “they’ve got troops in contact in Cambodia. Across the border, Sir.”

That got the colonel’s attention. He walked around the desk, faced Jones, and with a thick, reassuring Southern drawl said, “Well, now, what do ya’ll need, Lieutenant? What can I do to help?”

“They’re far beyond your artillery range,” Jones replied. “I just wanted you to be aware of the situation, and if you have any extra gunships on alert, we might need them real soon.”

“I think we can spare a light-fire team [two helicopter gunships],” the colonel said. “You can count on that.”

“Thank you, Sir,” Jones said, feeling he had done all he could as he hurried out of the office and to the B-56 TOC to monitor the radio.

THE NVA squad and the B-56 team faced each other in the clearing. Then Bao moved confidently ahead and began talking loudly to the NVA squad leader.

Looking down at his boots to hide his face, O’Connor casually pulled a piece of paper out of his pocket. He continued to stare at it while walking a few steps backward to stand beside Mousseau. The two men kept their heads down, studying the paper as if it were a map. Tuan came up beside them. “They think we’re from the other unit,” he whispered.

“Tell them we’re looking for a chopper that was shot at, that we heard go down,” Mousseau whispered back. Tuan nodded, but before he could move ahead and deliver the message, Bao turned around and commanded the team to search the thickest jungle area, as if he was in charge.

Mousseau and O’Connor immediately obeyed, but as they headed toward the clearing’s edge, Mousseau quietly said to O’Connor, “I think they might have seen your face. When Bao is clear, you take the left and I’ll take the right, but only if things look bad.”

Bao continued to bark orders, and the NVA leader waved what appeared to be a parting “good-bye.” Suddenly, the enemy officer called out harshly to Bao.

“They know!” shouted Tuan.

What happened next was instantaneous as Mousseau, O’Connor, and Bao went on autopilot: Mousseau targeted the enemy soldiers to the right, O’Connor took those on the left, and Bao, not privy to the impromptu plan, joined them in sending a hail of bullets into any still standing. Their marksmanship under pressure was astounding: all but two of the twelve NVA were dead within seconds. The two survivors dropped to their knees and returned fire. One let loose a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) that passed over the team’s head and exploded in the trees.

Mousseau, O’Connor, and Bao continued to fire while back-stepping into the jungle, where the rest of the team remained concealed, and Wright was calling for immediate extraction. Once the three men were clear, their CIDG teammates opened fire and killed the two remaining NVA.

Twenty or thirty yards into the jungle, the team formed another perimeter, and Wright informed Mousseau that the extraction slicks were “on the way and ready for a hot one.” Reaching into his shirt, he pulled a few documents from the waterproof pouch he kept secured by a lanyard around his neck and handed them to O’Connor. “Destroy these,” he said. “They’re no good to us now.”

As O’Connor and Mousseau ignited a chunk of C-4 explosive and lit the papers on fire, Wright motioned for the team to head back east toward their original insertion point. It was a risky move, but there were no other clearings in the vicinity, and the helicopters were inbound. Between their own firepower and the cover fire of the extraction slicks and their gunships, with any luck they’d be picked up and gone before a large-scale NVA reaction force converged on the area.

INSIDE THE Forward Air Controller’s Bird Dog, the radio sprang to life with the sound of gunfire, and the firm voice of Leroy Wright declared the obvious: “We are taking fire. Request immediate extraction. We are in heavy contact. What is your ETA?”

Almost an hour had passed since Jones had been relieved of his command of the mission. Yurman did not wait for an order, but immediately radioed the 240th reaction force on standby at Loc Ninh, telling aircraft commanders Jerry Ewing in Greyhound Two, Roger Waggie in Greyhound Three, and William Armstrong in Greyhound Four to launch immediately as the primary extraction team. McKibben would be reserve.

“Be advised,” Yurman said, “it’s going to be a hot one.”

The pilots at Loc Ninh, including McKibben, ran to their slicks and gunships that their crew chiefs—having anticipated what was to come—had prepped for takeoff. Jumping into his seat, McKibben got on the ship-to-ship radio and told Armstrong and Waggie to stand down, and told Ewing to crank. “We put them in,” he said. “We’ll get them out.”

But when he attempted to fire up the engine, there was no juice. His battery was dead, perhaps from monitoring the radio. Throwing his arms up in frustration, McKibben radioed back to the other pilots, “I’ve got a dead battery here—you’d better launch. I’ll catch up.”

Waggie’s crew chief, Michael Craig, piped in with the line he used whenever his aircraft got the green light for an extraction: “Let’s go get ’em, then.”

On the ground, the B-56 team was concealed just within the trees beside the clearing. As O’Connor and Mousseau divided the men into two groups of six, Wright contacted Tornow to reconfirm that they were ready for extraction and standing by at the “exact location” they had been inserted at nearly two hours prior. A hush had enveloped the jungle, an eerie calm after the explosive firefight. This quiet did not mean the men were alone. They waited, ears tuned for any sound—the creaking of a tree, the snap of a branch, the sudden cry of a monkey—that might betray the enemy’s approach. The harder they listened, the longer the minutes seemed to stretch.

WAGGIE AND Armstrong had launched from Loc Ninh a few minutes after Yurman’s order. They didn’t take the time to gain altitude; instead they flew low and fast, a couple of hundred feet above ground level, Waggie in the lead, his copilot, Warrant Officer David Hoffman, beside him. Behind Waggie, his crew chief, Michael Craig, pointed his M60 machine gun down toward the jungle canopy to cover the seven to eleven o’clock of the aircraft. The right-side door gunner was covering the five to one o’clock.

Fifteen minutes after they’d taken off from Loc Ninh, Yurman got a visual on both slicks, flying in a staggered trail formation with Armstrong about thirty seconds—or half a mile—behind Waggie. While James held the C&C slick in a wide clockwise orbit, giving Yurman an open view of the clearing—no longer considered the LZ, it was now referred to as the pickup zone (PZ)—he vectored the two Greyhounds in from the east, northeast. Standard operating procedure called for both aircraft commander and copilot to have their hands on dual controls that moved in unison; the commander kept a firm grip on the stick and did the actual flying, while the copilot “covered” the controls with a light hand, ready to engage the controls and operate the aircraft at a moment’s notice if the commander was wounded or killed.

In the event that either the pilot or copilot was wounded or killed, the crewmen behind could yank on a red lever on the back of each of their seats, reclining them. This allowed the crewmen to pull a wounded or dead pilot backward into the cargo area of the helicopter, clamp a spurting artery, or climb forward to assist the surviving pilot. If both pilots were dead, a crewman could take the stick himself—the stuff of crew members’ nightmares.

Greyhounds Three and Four were joined by their gunship support, Mad Dogs One and Two piloted by William Curry and CW2 Michael Grant. Curry, the gunship fire team leader, had—during the insertion—remained airborne at the border with his wingman, Grant, ready to provide close air support with their full complements of four thousand rounds of M60 ammunition, six thousand rounds of minigun ammunition, and fourteen rockets. After the first half hour of quiet, Curry and Grant had flown back to Quon Loi to refuel. They had been on their way to stand by on alert at Loc Ninh with Mad Dog Three and Four when the B-56 team’s emergency call for extraction came in.

Still concealed at the edge of the clearing, the team heard the faint but distinct whop, whop, whop of the approaching helicopters. Wright held off throwing a smoke grenade that would help the pilots identify their position because it would also reveal their location to any enemy in the vicinity. If the slicks hit the original insertion point, the men—now divided into two teams of six—would have a twenty- or thirty-yard sprint to the open side doors. A half hour later, they’d be sipping a cold one back at Quan Loi.

“Two miles out, Greyhound Three. Stay on your current heading,” Yurman radioed, vectoring Waggie toward the PZ at shorter and shorter intervals.

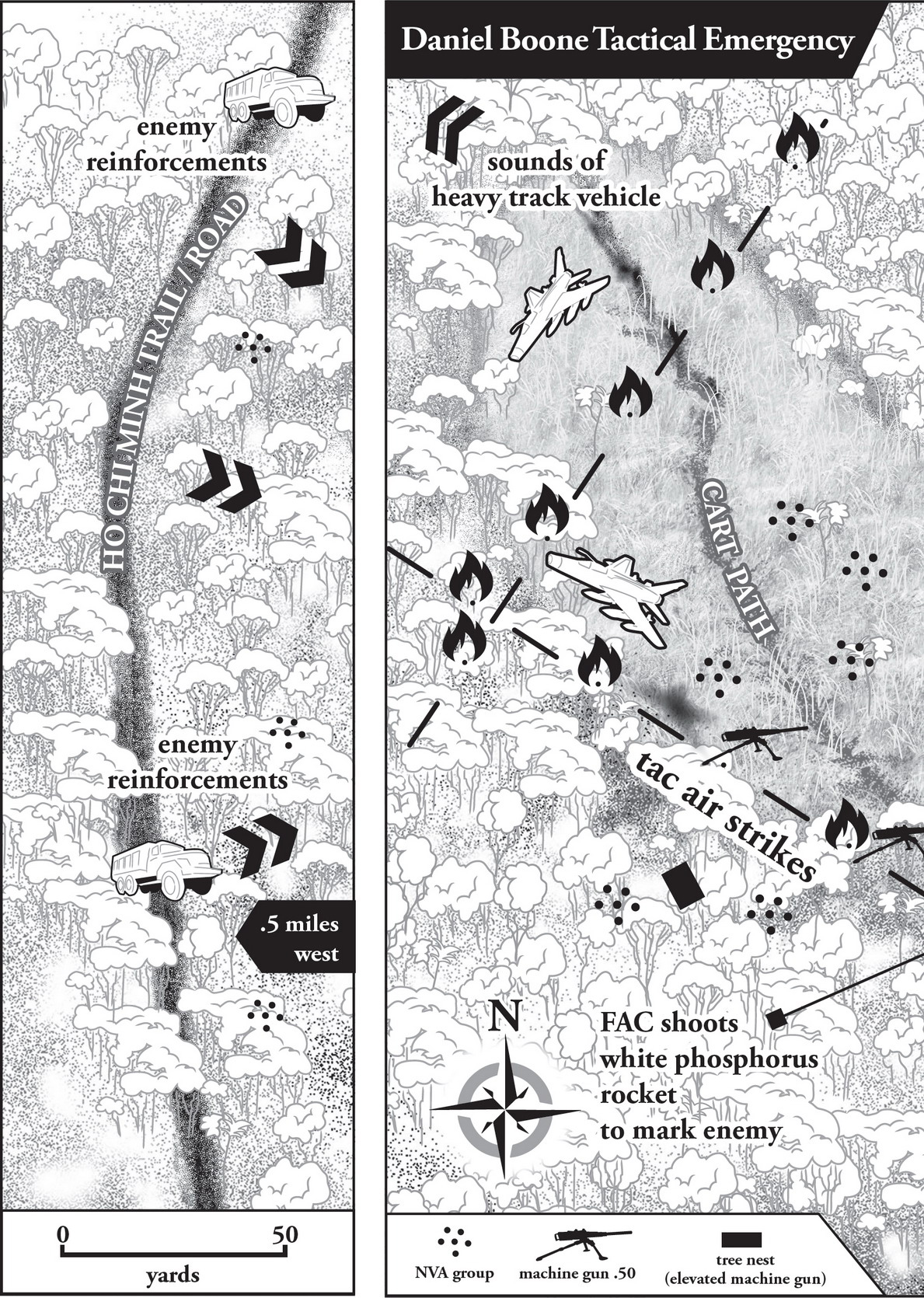

The B-56 team had readied themselves to sprint across the clearing when they heard what O’Connor described as “the roar of small-arms and heavy autofire” to the east that “intensified as the slicks approached.” In Greyhound Three, a half mile out, Waggie saw Mad Dog One lurch to one side, then start trailing black smoke.

Detail left

Detail right

The platoon sergeant for the Mad Dogs, Sergeant First Class Pete Jones, was so “short” he could almost taste the cold beer he planned to order on his freedom bird home in two weeks. But his crew chiefs had been flying so much the previous week, he’d decided to give one of them a break by volunteering for the mission, aboard Mad Dog One. Now the gunship was bucking through the air, and he was peppered by fragments of bullets as they ripped through the floor and bounced around the cabin. His gunner—a guy everybody called Swisher because his fake front teeth made a swishing sound when he talked—was blown off his M60 and lay motionless on his back, his eyes closed.

Jones looked for a wound, then found it: a bullet had hit the edge of Swisher’s helmet and entered his forehead, leaving a tiny hole from which blood oozed. The impact had cracked the helmet from front to back. Jones barely had time to register that Swisher was dead before he smelled the burning oil, saw the smoke, and heard the change in the tone of the engine. The helicopter banked away from the PZ, leveled off over the trees, and began to gain altitude as it accelerated west.

An instant later, Waggie flew Greyhound Three into the same wall of anti-aircraft fire. He could hear the bullets coming up around his feet, distinct thuds and pings that penetrated the Plexiglas nose bubble, ripped through the thin metal skin of the aircraft, and impacted with the underside of their armored seats.

Leaning over their M60s, the gunners returned fire into the jungle, but the deep, stuttering roar from Michael Craig’s gun stopped abruptly as a bullet cleared the underside of his “chicken plate” (ballistic armor worn by air crews) and tore into his ribs and chest. The impact from the round flung him up and backward onto the cabin floor. “Your crew chief is hit!” yelled the Special Forces bellyman on board to assist with the extraction. He reached over to help Craig just as the door gunner was spun backward by a bullet to the shoulder.

Copilot Hoffman instinctively gripped the controls and yelled, “Breaking right!” as Waggie radioed Armstrong, who was hot on their tail in Greyhound Four and about to fly into a wall of fire. “Bank right, Greyhound Four, bank right! We’re taking hits! Abort extraction! Abort extraction!”

O’CONNOR THOUGHT it sounded as if the slicks “had the whole jungle firing at them,” yet the area surrounding the team remained silent. Suddenly Greyhound Four raced into view over their left shoulders, skimming the treetops from the northeast. Its nose flared upward to arrest its speed and the slick dropped into the clearing, whipping and flattening the grass below in the hurricane created by the rotor wash. The helicopter hovered there momentarily about a hundred yards away from the men, close to where the team had originally encountered the woodcutters.

There was no time for Wright to signal Armstrong—smoke or mirror—because a half-dozen NVA immediately emerged from the trees adjacent to the helicopter. They approached Greyhound Four, waving. The slick’s skids tapped the ground, then settled into the grass, ready for the team to board.

My God, thought O’Connor, they think that’s us! At the same moment, the team’s CIDG came to the same realization and fired on the NVA that were nearing the helicopter. From within Greyhound Four, Specialist 4 Robert Wessel, the right-side door gunner, identified the CIDG’s fully automatic gunfire as enemy fire and strafed the B-56 team’s position.

“Cease fire!” Wright yelled at the CIDG. The guns fell silent, and Wright shouted into his radio, “Get that chopper back in the air!” There was no response, and he switched channels, attempting to reach the forward air controller, the C&C slick, the extraction pilot across the clearing—anybody who could get the message that Greyhound Four was about to be ambushed by the NVA: “Get that chopper back in the air! Get them out of there! That is Charlie, I repeat…”

GREYHOUND FOUR’S pilots and crew were watching the approach of what they assumed was the American-led team dressed in their NVA-disguise uniforms when Mousseau and O’Connor took aim and dropped the lead NVA soldier. In response, the remaining five NVA raised their AK-47s and charged, opening fire on the helicopter. Gunner Wessel leveled his M60 at the group, their bodies flung backward thirty yards from the aircraft.

Wright ordered Mousseau to try to signal the helicopter with a mirror. If that didn’t work, they would risk a grenade of red-and-green smoke in front of their position. As O’Connor flipped switches on the radio, holding the antenna overhead, cursing, and praying for a signal, Wright tapped him on the shoulder and pointed across the clearing.

Within the tree line, a column of some thirty NVA was rapidly nearing the helicopter.

MAD DOG One, mortally wounded and hemorrhaging—oil, hydraulic fluid, and fuel spraying out over the jungle—continued flying west, farther into Cambodia. Curry fought the gunship’s controls to gain altitude and mileage, willing it into a bank that would bring the helicopter back on an eastern bearing. At the same time he scanned the ground below for a place to set down. There was the Ho Chi Minh Trail with its stream of enemy trucks, the PZ he’d just been shot out of, and the green of the jungle. So much green.

Alone in the backseat with the dead gunner, Swisher, Jones gripped his M60, acutely aware of the unnatural sounds of the laboring aircraft. He kept glancing down at Swisher on the floor—his closed eyes, the speck of blood in the middle of his forehead, and that perfect vertical crack down the center of his helmet. Out the window, the horizon receded while the gunship shook, rattled, and fought to gain altitude—two hundred feet, three hundred, four hundred; from hell to purgatory they climbed. They were no longer taking fire, but this was dangerous air, low enough to be reached by enemy small-arms ground fire and high enough to be spotted and tracked by anybody looking up.

And then there was a very distinct quiet of an engine suddenly stopping. “Hang on,” Curry said calmly over the intercom. “We’re going down.”

Curry had managed to gain enough altitude that he could initiate the helicopter’s version of a glide, autorotating so that its blades can catch the wind as it falls like a rock; if the pilot is able to conjure up the necessary “glide,” a powerless helicopter can land without certain death to all those on board.

This is something all the pilots had done during training over a big clearing or a runway, but not over solid jungle full of enemy forces. Jones, who felt as if his stomach was pressing up against his tonsils, could make out plenty of them through the trees below as they fell. He also caught a glimpse of a bomb crater, and then Curry flared from his autorotation glide and hit hard on the skids, landing in a postage stamp–size clearing. Somehow, he had brought them down in a barely visible speck that would have been hard to hit with full power.

Jones went to unlatch his M60, then realized he had spent his last bullets on the pass over the PZ. Grabbing his rucksack, which held grenades, a couple of C rations, and extra ammo for his M16, he jumped from Mad Dog One and hurried to the front of the helicopter to help Curry and his copilot, David Brown, both with .38s in their holsters, carry Swisher.

As Jones leaned over the body, Swisher opened his eyes, startling all three men. What appeared to be a bullet hole was actually a small gouge from shrapnel, Jones realized, as he examined Swisher’s head. The impact of the shrapnel had split his helmet and knocked him out cold. Though awake, he was dazed, looking around blankly while Jones and Brown carried him from the wreckage of the helicopter to the bomb crater some twenty yards away and settled inside its berm. There they waited, scanning the green around them for NVA while Curry called in a report over his emergency radio. A second later their wingman, Grant in Mad Dog Two, swooped overhead, marking the spot but passing them by, not wanting to further alert the enemy to the location of the downed aircraft.

GREYHOUND Four—turbines still whining at full power, M60 barrels still hot—sat in the grassy PZ, empty except for the six dead NVA soldiers to its right. Inside, the pilots and crew were electric with post-firefight adrenaline and feeling uncomfortably exposed without gunship support; per standard operating procedure, Mad Dog Two’s pilot, Michael Grant, had chased after Mad Dog One as soon as he saw it was in trouble, while his copilot, Chief Warrant Officer Ron Radke, attempted to reach them on the radio.

In Greyhound Four, Specialist 4 Gary Land and Robert Wessel, crew chief and right-door gunner, guarded their flanks and searched for the B-56 team while Armstrong and his copilot, Warrant Officer James Fussell, scanned in front of the aircraft. Armstrong’s grip—slick with sweat—was closed tightly on the controls, ready to pull pitch and exit at a moment’s notice.

“Where the hell are they?” Armstrong said aloud into his microphone. The slick had been on the ground too long already. He asked if anyone could see a panel—a bright orange-colored fabric square used to identify U.S. and allied forces. “Smoke?” came his voice over the radio. “Anything?”

“Negative,” Land and Wessel reported back. The glint from the opposite side of the clearing, where Mousseau was working his signal mirror, was not visible to them. Nor was the large group of NVA moving in at the helicopter’s twelve o’clock.

Thirty seconds more, Armstrong told himself. He counted down as he tried to reach the FAC for a situation report on the team. Had they been killed? Were they lying low? Were they on the run and ready to burst from the trees any second? He didn’t want to leave them, but he had to get some sort of signal, ETA, or radio contact ASAP.

WATCHING THE NVA column press forward, Wright waited a full minute before he was certain the aircraft commander had not received his communication to get the slick the hell out of there. A hundred yards was too far to run to the helicopter; the risk was too great that his team would get cut down halfway through.

Wright tried the slick’s crew on the radio one last time. Nothing. He ordered Mousseau to fire a light anti-tank weapon into the NVA column; the rocket-like projectile streamed across the clearing while Wright and O’Connor pumped out grenades from handheld launchers, lighting up the distant tree line with a series of explosions.

The NVA broke loose from the jungle and charged the front and right side of the helicopter. To the left of Greyhound Four, another cluster of enemy soldiers charged out from where they had been lying in wait.

Unarmed except for the .38 revolver he kept strapped to his thigh, Fussell could only watch the attack from his copilot seat inside the helicopter. He heard the spray of enemy bullets hitting the slick and the hammering automatic fire of dual M60s as crew chief Land on the left and door gunner Wessel on the right opened fire, targeting the lead NVA. At his feet, green-colored movement under the nose bubble caught his eye. A soldier was trying to aim his AK-47 upward into the cockpit, but the space between the ground and the helicopter was too short. Fussell shot down through the glass, feeling the kick of the revolver three times as he yelled into his mic, “Let’s go! Let’s Go! Let’s go!” Armstrong was already bringing Greyhound Four off the ground.

Glancing back into the rear of the helicopter, Fussell saw Land working his M60, laying down fire into what appeared to be dozens of green uniforms rushing from the trees through the grass, bayonets fixed on their AK-47s. The crackling thunder of the incoming and outgoing weapon reports and rounds was deafening. NVA bodies were flung haphazardly in the grass—several with their faces torn off by the 7.62 mm bullets—but the charge was relentless.

It took a moment for the sudden buzz in Fussell’s ears to register as silence from behind him. Both gunners had stopped firing. Pushing against his seat restraints, Fussell lifted up and looked over his left shoulder. He could see Land sprawled behind his gun, his boot blown open, revealing the raw meat that had been his foot. Blood pooled on the floor from a severed artery farther up his leg. Over his right shoulder, he glimpsed Wessel pulling himself back up to his gun. His cheek and neck were ripped open, his jaw hanging loose, dripping blood.

A higher-pitched tat-tat-tat joined the enemy fire as James Calvey—the Special Forces medic who was bellyman on the flight—grabbed his carbine and pumped rounds into the chests of two NVA soldiers a few feet away from climbing on board. Though severely injured, Land managed to pull his legs back up into what little cover the open doors of the helicopter afforded. He manned his weapon and rejoined the firefight while Calvey applied a compression bandage and tourniquet to his leg to stop the bleeding.

Calvey moved to Wessel, who had been shot through the neck but stayed on his gun; he pushed Calvey away as he attempted to bandage the wound. Picking up his M-4 carbine, Calvey began providing suppressive fire. He was alternating between the right and left doors when a bullet hit his elbow, traveled up his arm, and exited behind his shoulder. After quickly checking his wound, Calvey continued to fire, taking out the lead elements of the relentless enemy charge.

Another flash of motion drew Fussell’s attention forward just in time for him to shoot the NVA behind the bayonet-fixed AK-47 coming through the side window. To his left, Armstrong leaned forward in his armored seat, then sat back upright, blood pouring from under his flight helmet and down his forehead and neck.

Fussell gripped the controls, but they jerked in his hands.

“I got it!” Armstrong barked. The tail boom drifted lazily, nose pointing toward the tree line to the southwest. The controls felt heavy to Armstrong—like when a car loses its power steering—and he fought them for every inch of slow, steady, vertical climb. For the past few minutes he had been concentrating so fiercely on getting the helicopter launched that he had barely heard the gunfire or seen the attacking enemy. He knew from the initial kicks he’d felt on their descent into the clearing that their hydraulics had been shot out. He didn’t realize, however, that he’d been shot in the back of the head. He was unaware of the blood that soaked his shoulders and restraining straps, or of the fact that Fussell was poised, ready to take over the second Armstrong succumbed to his injury.

The turbines labored and the rotors beat at the thick, humid air. Brass bullet casings rained from both sides of the helicopter as the wounded door gunners blasted away at the NVA, who were firing on full automatic up into the belly of the aircraft. Seventy-five feet up, the ground fire became so intense that Armstrong could no longer wait for the blue-sky horizon; he plowed forward into the wall of green near the treetops, branches disintegrating as the slick’s main rotor cut a channel. At any moment an old-growth hardwood limb could drop the aircraft from the sky.

Fussell was shocked to find himself eye to eye with an NVA soldier who was more than a hundred feet off the ground in a tree stand, or nest, mounted with what looked like a heavy-caliber machine gun. The man likewise seemed shocked, frozen into paralysis by the sudden appearance of the helicopter tearing apart the jungle in front of him. If he opened fire at all, it was after Greyhound Four passed his position.

An instant later, the slick broke through the canopy and raced away, a mist of finely chopped leaves, vines, and branches drifting down in its wake. That was when Armstrong realized that he was seeing his instrument panel through a narrowing tunnel, and then he was seeing double and felt, for the first time, not quite right.

“Take the controls,” he said to Fussell. “I can’t focus.”

Tightening his grip, Fussell set his course east, back to South Vietnam. “What’s your heading?” Armstrong asked, rubbing his eyes to try to clear his vision. His hands came away covered in blood. Out the front of the Greyhound, the horizon looked different. Am I in shock? he wondered, peering at the pancake-flat jungle beneath him. He wasn’t picking up the landmarks he’d noted on the way in. No, not shock. Just confused. Something isn’t right.

The radio finally came back to life and Fussell was able to broadcast their SITREP, situation report: “My AC [aircraft commander] and entire crew are wounded; hydraulics are out. I’m coming in.”

Unbeknownst to Fussell, the magnetic compass had been damaged. They weren’t heading east; they were flying due west—deeper into Cambodia.