12

IF SOMEONE NEEDS HELP…

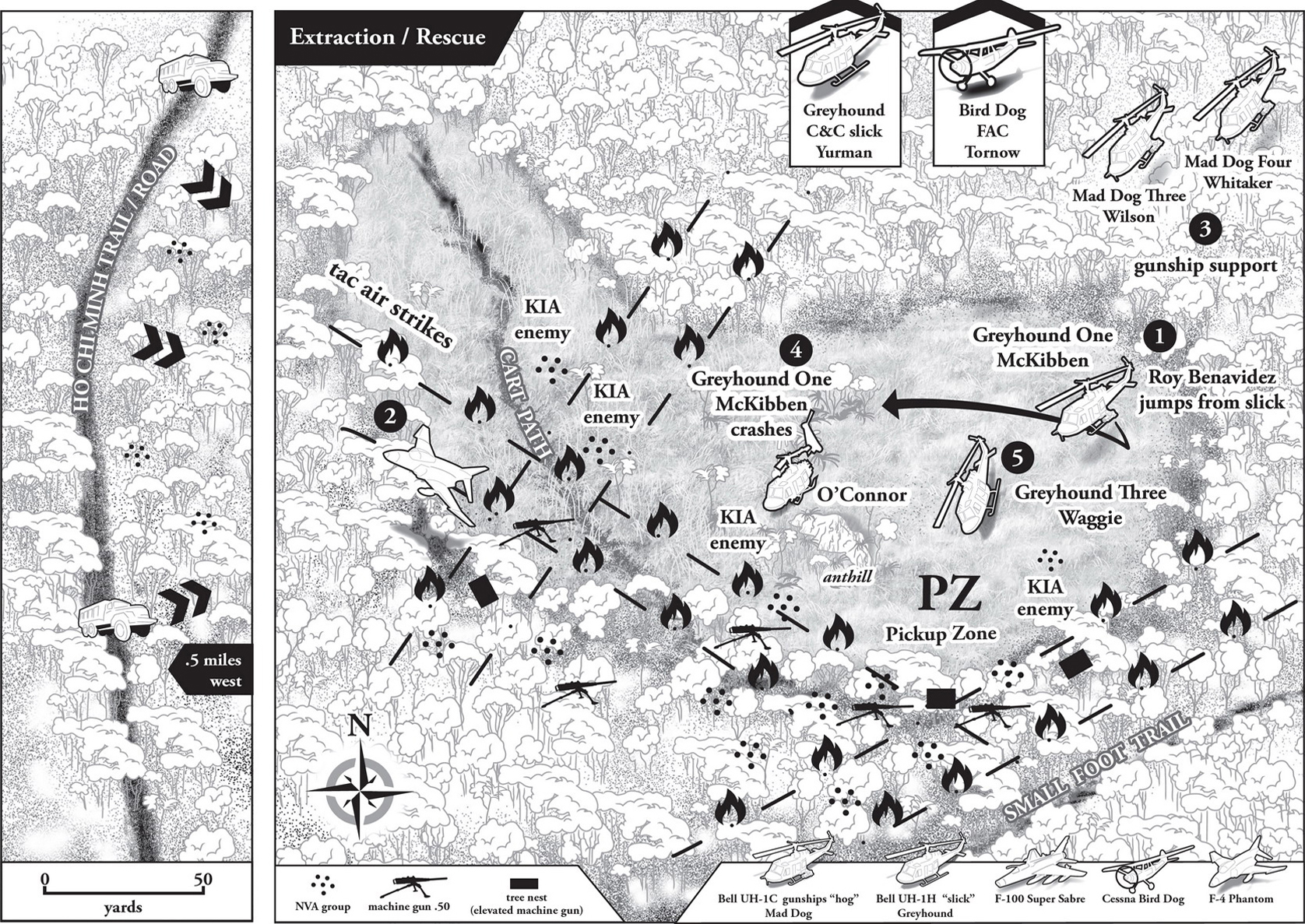

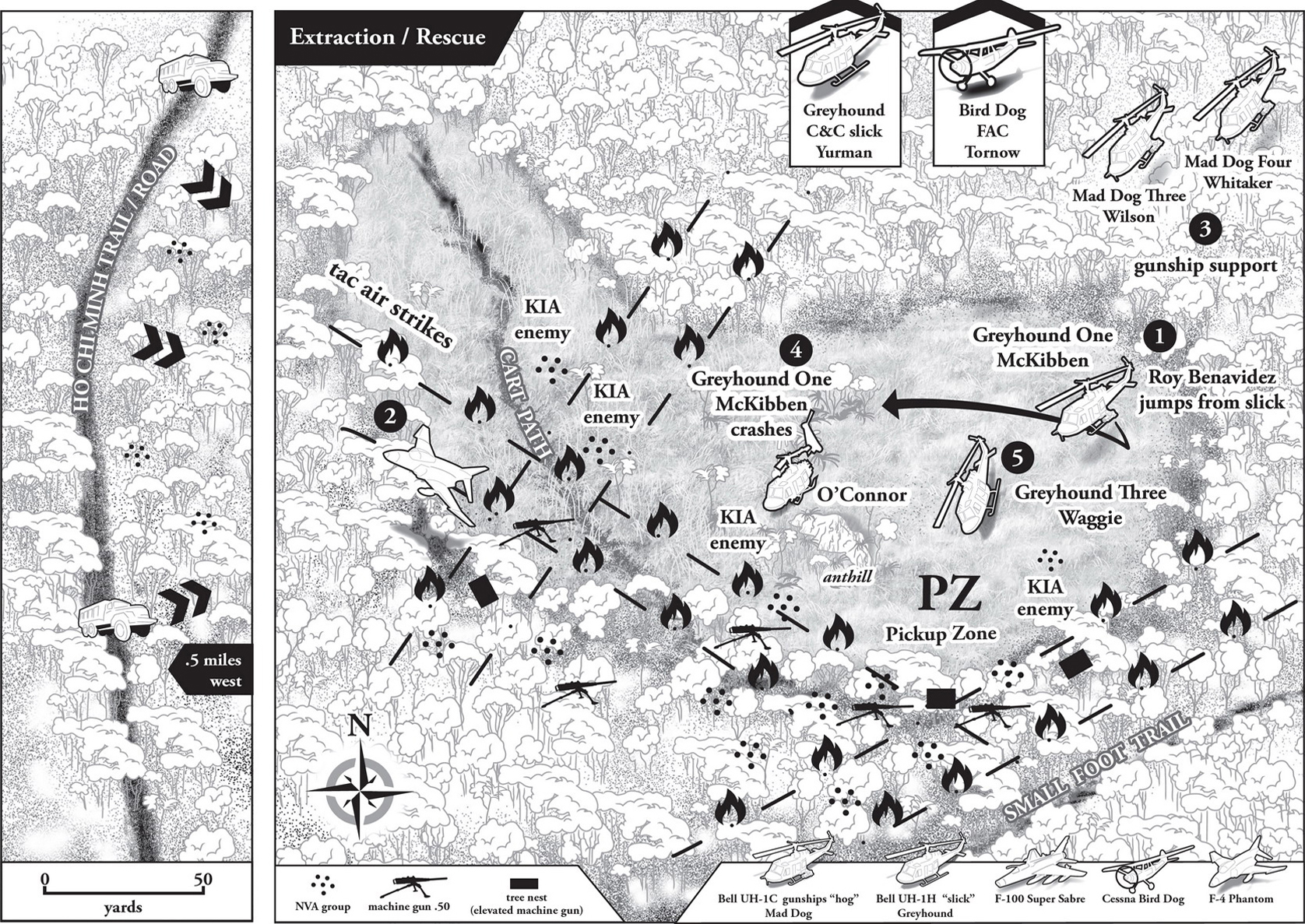

AT LOC NINH, Roy Benavidez gently set Michael Craig’s body on a stretcher beside Greyhound Three. He said a prayer, then walked away, leaving Roger Waggie and David Hoffman kneeling beside their dead crew chief.

Within a few minutes, two more helicopters from the 240th returned from the border. The first was Mad Dog Two, the second gunship in the fire team for Greyhound Three and Four’s extraction attempt. Pilot Michael Grant had been forced to abort his support run when Curry in Mad Dog One began trailing smoke and banked away from the PZ. Grant’s aircraft had been shot up even more than Curry’s, but somehow he’d stayed in the air long enough to help cover the downed crew until backup arrived. His control system was badly damaged, however, and Grant had been uncertain that he could make it back the extra miles to Quan Loi—the designated base for refueling, rearming, and maintenance on the mission.

Following close behind was Larry McKibben in Greyhound One, carrying Curry and his crew—all of whom had shrapnel and/or bullet wounds. They were immediately transferred to a medical transport helicopter and whisked away to the field hospital at Quan Loi.

Roy walked from helicopter to helicopter, overhearing conversations and collecting snippets of information from their crews: “Never saw ground fire like that before…” “If there’s not at least a battalion of NVA down there…” From what he was witnessing—the radio transmittals, the firsthand reports from the extraction attempts, the shot-up aircraft, the death of Michael Craig—Roy held little hope for the team’s survival.

He returned to Greyhound Three, where Waggie and Hoffman were going over their slick and counting bullet holes: fourteen in all, the worst of them a gaping, jagged gash on the panel that covered the tail rotor driveshaft. With closer inspection, they realized that it had been caused by a bullet ricocheting off a bearing; they weren’t sure how much longer this aircraft could fly.

Roy, who still hadn’t found out which Special Forces team members were involved, asked Waggie if he had any idea. Waggie didn’t know their names, but he recalled seeing “that big black sergeant” among them when he’d flown backup during the insertion. That man, Roy suspected, was his friend Leroy Wright.

There was a hum of turbines, and Roy saw the rotors on Larry McKibben’s slick begin to spin. Without a moment’s pause, he grabbed a medical bag that had been left on the helicopter pad and ran to Greyhound One. In back, crew chief Dan Christensen and his gunner, Nelson Fournier, were behind their weapons.

“You going back in?” Roy asked.

“We’re gonna try,” said Christensen. “At least drop them some ammo.” He held up an assault pack of ammunition.

“I’m in,” Roy said. “You need a bellyman.”

Christensen informed McKibben over his intercom, and McKibben looked back to see Roy, medical bag in hand, already halfway inside the slick. He gave Roy a thumbs-up, and Roy climbed all the way in and set the medical bag on the floor beside him.

Then they were airborne, flying low over the pancake-flat farmland of the Mekong Delta, leaving the ominous round hump of Nui Ba Den rising three thousand feet above the delta in their wake. The American radio relay station on the mountaintop—which Roy had used to keep tabs on a different Special Forces team the night before—was critical for missions into Cambodia.

Everyone on board was silent and stone faced—and Roy was just another passenger taking the bus to work. Christensen and Fournier were cordial strangers; they looked out their windows down the barrels of their M60s, keeping to themselves, leaving the driving to the guy on the stick up front.

Although they were all working on the same team and had the same objective, they had little to say and knew little to nothing about one another. Roy didn’t know that Larry McKibben, the pilot, was a fellow Texan, with a sister whom he missed like crazy about to graduate from high school, or that he sent home tape-recorded letters every chance he got. Or that the copilot, Warrant Officer William Fernan, was, at twenty-six, the old man on the slick’s crew, with a wife named Diane and a degree in biology from the University of Washington that allowed him to actually identify many of the plants and trees of the jungle they were flying over.

Nor did Roy know that Christensen was a twenty-four-year-old father of three from Wisconsin who spent his summers in the Dakotas baling and combining wheat and hay. Or that nineteen-year-old Fournier went by the nickname “Sonny Boy” back home and was a favorite human jungle gym for his nieces and nephews. One of Fournier’s proudest moments, after getting his helicopter door gunner’s wings, had been winning a radio in a raffle right before he’d deployed. It was the only thing he’d ever won.

As he watched the world rush by below, Roy pondered his spontaneous decision. Was it because he couldn’t sit back and listen to his friends getting slaughtered and not do anything about it? Was it an involuntary response, like when he was a kid, jumping into a fight without considering the consequences? Was it his Yaqui blood, the ancestral warrior in him? Or was it rooted in the lesson he’d learned from Grandfather Salvador? When someone needs help, you help them.

He noted the aircraft commander and copilot’s personal weapons: two M16s strapped on the back wall. In the event of a crash landing, the crew chief would hand these weapons to the pilots as they exited the helicopter. Both gunners also had holstered .38s strapped to their thighs, and Roy realized with a start that in his haste he had broken the cardinal rule of any Special Forces soldier; the most basic rule of a buckprivate grunt. He was going into battle without his weapon.

Had this been a regular mission, he’d have brought along his carbine and revolver as unconsciously as he’d bring his arms and legs. But he was not on a regular mission, and he carried none of his normal survival gear: radio, a compass or two, pen flares, a map, signal mirror, two or three shots of morphine. He had no web gear, the load-bearing, vest-like carryall that accommodated the standard twenty-one magazines of ammunition, his pistol, water canteens, smoke canisters, and grenades. He had no rucksack, which carried extras of all the items above, plus a Claymore mine, explosives, medical supplies—including a blood expander and IV bags—and other mission-specific equipment. Strapped to the side of the rucksack was a short machete called a “banana knife,” and, shoved around anything that might rattle, he kept his poncho and poncho liner, as well as food rations to sustain him for a day or two. Beyond all of this, and his personal weapon, he would carry an extra weapon—a grenade launcher or a sawed-off shotgun.

Today, as he sped to the massive firefight taking place within Cambodia, Roy had with him the medical bag, the small bottle of Tabasco sauce he’d intended to use for the breakfast he hadn’t eaten, and his recon knife, eight inches of steel blade custom made without a serial number or identifying marks at the Counterinsurgency Support Office in Okinawa, Japan.

He was covered head to toe in tiger-striped camouflaged combat fatigues, but he might as well have been wearing one of the loincloths of the Montagnard tribesmen employed by SOG—something Green Berets had been known to do while training and bonding with the indigenous warriors who fought beside them. They called it “going native.”

Not long after 3:00 p.m. Ewing in Greyhound Two was orbiting east of the PZ, waiting for the air strikes to stop so he could follow in as second extraction slick to whoever was inbound, when Yurman came over the radio and instructed him to come around and begin a descent for a low-level vector into the PZ. Taken aback, Ewing replied, “It’s not my turn,” then immediately thought, What the fuck? Did I really just say that?

“We’ve got an opening; I need you now,” said Yurman, and Ewing rogered, circled, and set up for final approach.

“I’m here, Greyhound Two,” McKibben announced over the radio. “I’ll go in next.”

“Negative, Greyhound One,” Ewing said. “I’m already on my way in.”

“Nope, my turn,” said McKibben as he banked wide around Ewing and cut in front of him.

“Okay, Greyhound One,” Ewing replied. “I’ll go down with you to draw some fire.”

Roy listened in over the radio while McKibben flipped to the ground frequency and announced that they were incoming. The only response was gunfire.

“It’s going to be hot,” McKibben told his crew. “If they can’t get to us or we can’t get to them, we’ll drop ammo.”

Both Christensen and Fournier checked their weapons and positioned themselves with their M60s down and forward, ready to provide suppressive fire. Looking forward through the cockpit, Roy saw nothing but treetops and smoke.

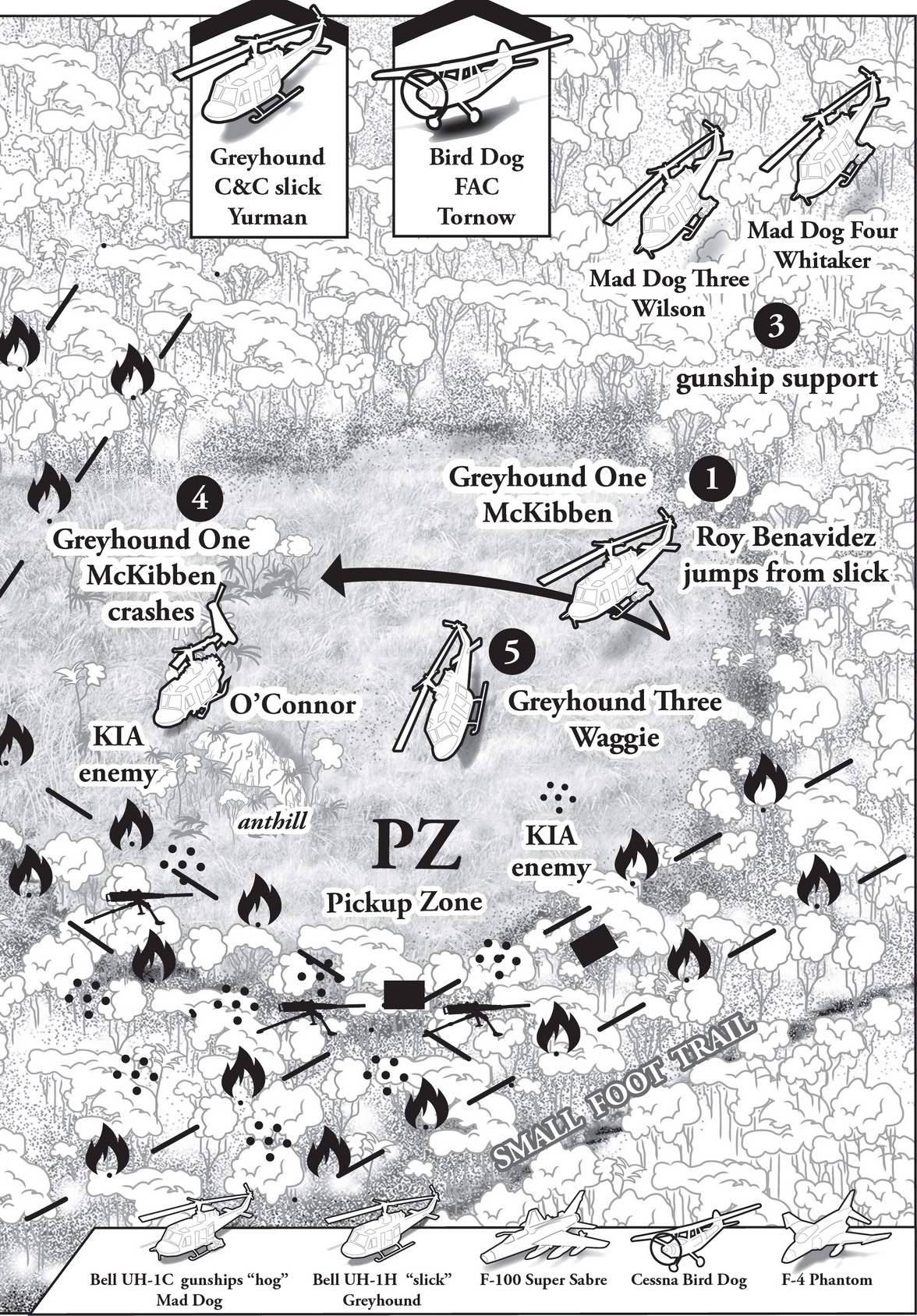

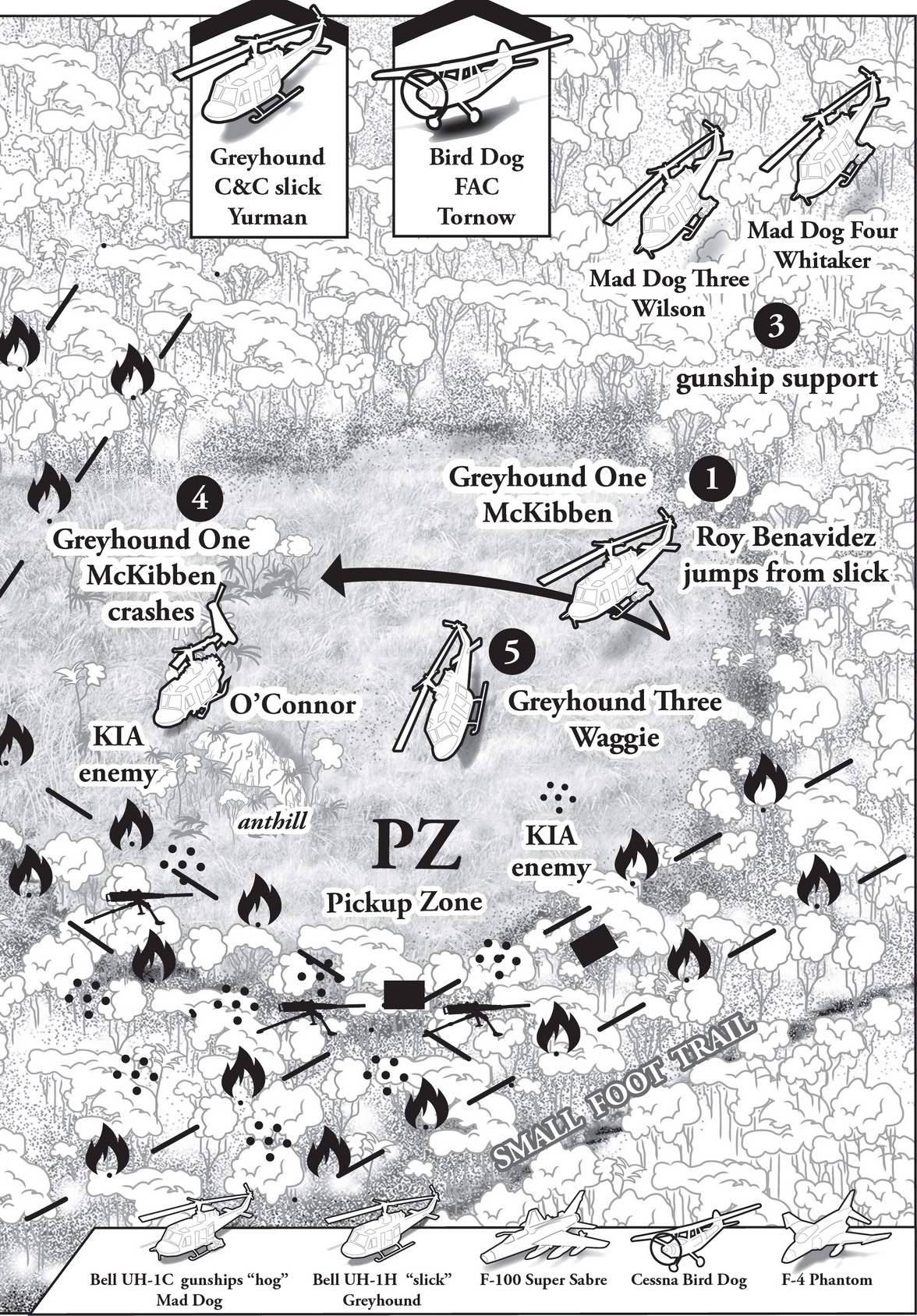

O’CONNOR WAS lying behind Wright’s body, bleeding steadily, fading in and out of consciousness, waiting to be overrun, when through the din of gunfire he heard the faint but distinct whop, whop, whop of approaching helicopters.

The beating rotors coaxed him away from the descending darkness, allowing a sliver of hope. He envisioned a swarm of helicopters, brimming with weaponry and soldiers, a “strike force coming en masse to recover what was left [of us],” he would write in his statement, “but instead a lone slick flew into the middle of the PZ and hovered with door gunners blazing.”

The enemy fire shifted from the team on the ground to Greyhound One. McKibben had dropped into the PZ a hundred yards east of the thickets and flared to a hover ten or fifteen feet off the ground. Faint streaks—NVA tracer rounds—crisscrossed from both sides of the clearing while the door gunners returned fire, blasting away at the tree line. To Christensen, there were so many barrel flashes it looked like the blinking lights on a Christmas tree.

“We’re taking heavy fire,” McKibben reported over his microphone. “I don’t think we can get in close enough.” He began to pull pitch.

“Wait!” Roy shouted back. He edged his way to the door of the slick. “Just get me as close as you can. I’ll get to them.” With one hand on the medical bag and his feet dangling, he watched the grass swirl about from the rotor wash, ten or fifteen feet below, while Fournier strafed the trees with his M60 on full automatic. Taking a deep breath, Roy crossed himself several times, pushed the medical bag out the door, and jumped.

PETE GAILIS was looking down on Greyhound One from Mad Dog Four as his pilot, Gary Whitaker, dove into the PZ and released two rockets. Warrant Officer Cook, the copilot, directed his miniguns on a group of NVA, and seventeen-year-old Specialist 4 Danny Clark, an infantryman turned door gunner, swung his gun methodically from target to target, dropping the enemy with short bursts from his M60. Having been outnumbered himself on a search-and-destroy mission just months prior, Clark knew that every NVA he killed from the air took some heat off the guys on the ground.

On the other side of the gunship, Gailis had swung his M60 on a smooth, steady arc to the left, providing suppressive fire into the southern tree line. The helicopter banked, and he could see Greyhound One drop down suddenly, flare, and hover off the ground in the northeast corner of the PZ, some distance east of the beleaguered team.

As tracers flew everywhere, several NVA soldiers ran into the open and sprayed the slick with bullets. A body went out its door and Gailis thought, Oh my God, they’re shooting ’em out of the aircraft! It was inconceivable to him that anyone would “willingly jump into the battle when everybody on the ground wanted out.”

O’Connor watched the Special Forces soldier in his jungle fatigues jump from the helicopter and disappear in the grass. Then he was up and running hard, following in the wake of the slick that had dropped its nose and raced toward the team’s position, gaining altitude as it went. O’Connor provided cover fire for the lone soldier, pausing briefly to look up as the slick passed directly overhead. A crewman tossed out a web belt of ammo pouches, but its trajectory took the belt far beyond his position, landing to the west of the thickets.

Detail left

Detail right

Just a few strides into his mad dash, fifty yards from O’Connor, the soldier abruptly went down. He was back up and running a moment later, heading for the nearest cover: the northern thicket where Mousseau was also providing cover fire.

Bullets tore up the grass around the soldier as he ran, and at least two RPGs were fired at him. He went down a second time.

Mad Dog Four banked low and tight over the trees and came back around, with both Gailis and Clark firing on automatic, raining brass over the floor of the helicopter and out the doors into the PZ below. When the M60 ammo, mini-gun ammo, and rockets were gone, Whitaker made one more pass to draw fire, and both gunners took up their M16s and fired their remaining bullets as Gailis searched the grass for the soldier he thought had been shot from the slick.

IN THE northern thicket, Mousseau was scanning for the Special Forces soldier when he heard someone calling out softly yet urgently, “Leroy! Leroy!”

“Who is that?” Mousseau called back.

“It’s Benavidez,” Roy answered. “I’m coming in.”

Roy crawled through the trampled grass into the blood-soaked perimeter, up to Mousseau who was propped between a CIDG body and the roots of a small tree; a few yards away, Bao and two more CIDG were prone at their weapons. Wiping blood from his eyes—his face had taken shrapnel from the RPG blast—Roy examined Mousseau’s bandage then pulled up his own pant leg to find that a bullet had passed completely through his calf.

“Where’s the rest of the team?” he asked, and Mousseau nodded toward the other thicket. “Okay,” said Roy, “let me have your radio. We’re getting out of here.”

A moment later, FAC Tornow, Yurman, the Greyhounds, the Mad Dogs, the fighter-bomber pilots—all the personnel who had been fighting to keep the team alive on the ground and everybody else who had been monitoring the deteriorating situation from afar—were surprised to hear a new voice on the ground. He identified himself with the call sign Tango Mike Mike and reported he was with the team.

“They’re in bad shape down here,” Roy said. “Multiple wounded. Request immediate medevac.”

He looked over to the adjacent thicket and spotted O’Connor. “You okay?” he shouted.

“Ammo?!” O’Connor yelled.

“Who’s alive?!”

Chien had been killed, leaving just O’Connor and Tuan. He raised two fingers. “We’re going out!” Roy yelled back. “Try and get over here!”

Tuan was semiconscious when O’Connor told him they were getting out. “We gotta move,” he urged, but Tuan was too weak from blood loss to do anything but lie there. “Don’t leave me here,” he pleaded.

“I won’t,” O’Connor assured him. “Let’s go.” O’Connor began to slide forward on his side, guarding his stomach wound, while physically pushing the interpreter in advance of him—a few painful inches at a time. A slick passed overhead—either McKibben or Ewing targeting the enemy with long bursts of fire that were lost in the steady reports of the AK-47 fire, larger-caliber machine-gun fire, and mortar rounds.

A few more inches and O’Connor faced the gap between the thickets where the first two CIDG had fallen hours earlier. Machine-gun fire raked across his path, and Roy waved him back.

As Roy threw a smoke grenade, O’Connor squirmed backward to the modest but effective cover of the anthill, pulling Tuan with him. “Don’t leave me here,” Tuan said again. “Don’t leave me.”

GREYHOUND ONE was providing cover fire over the PZ when McKibben heard Roy say, “Identify smoke.”

“I see green smoke,” McKibben replied. He came in fast over the treetops and flared to a hover a few yards west of the northern thicket—placing his slick between the team and the western tree line, where the heaviest concentrations of enemy fire were coming from.

The rotor wash turned the thick, billowing green smoke into a swirling haze. Gunfire erupted from the clearing’s edge, and Fournier answered from the right side of the helicopter, steadily firing rounds from his M60 at knee- to chest-level—a horizontal line of protective lead into the tangle of charred, napalmed jungle. A second slick, Ewing’s, came in a hundred feet off the deck, closer still to the trees, drawing some fire while his right-door gunner strafed even deeper into the vegetation.

Roy stayed crouched in the thin cover of the thicket beside Mousseau and his CIDG, all wounded. He picked up an AK-47, likely the one Mousseau had retrieved from one of the dead, and then—under the temporary cover offered by Greyhound One’s door gunners, Roy said, “Let’s go!” In a hunched-over run, he ushered Mousseau, Bao, and the other two CIDG toward the helicopter. They limped and dragged their way toward the open door of the slick as Roy stood beside the skids, covering them until the final man had heaved himself on board. Then Roy signaled to McKibben, directing him to the other thicket.

Holding Greyhound One steady, its skids a couple of feet off the ground, McKibben gently nosed down and crept forward while Roy jogged alongside, firing into the southern tree line. They got as close to the thicket as possible—some twenty feet away—and Christensen had a clear line of fire in the ten and eleven o’clock of the southern tree line. Anything that moved, he hit.

Roy darted the distance and dove down beside O’Connor, leaning up against the base of the anthill. Tuan was six feet farther down the berm-like hill, and a few feet farther still was Leroy Wright’s body.

“Can you walk?” Roy asked O’Connor.

“I can crawl,” O’Connor said, then gestured to Tuan, who had fallen unconscious again. “He can’t.”

“What does Leroy have on him?”

“The SOI [standard operating instructions] and some maps in a green plastic pouch tucked in his shirt.”

Noticing that O’Connor carried only a .22 pistol, Roy handed him the AK-47. “Cover me,” he said, and crawled through the grass to Wright’s body.

Unbuttoning and reaching inside his friend’s shirt, he pulled out the pouch of sensitive material. Wright’s camera bulged in his chest pocket, and he took that as well. Hearing movement, Roy quickly crawled back to Tuan, grabbed two grenades from his web gear, pulled the pins, and tossed them into the tall grass just beyond Wright’s body. Two NVA jumped up to run, but the grenades exploded and took both men down.

Slapping Tuan’s face, Roy was able to revive him enough to get him to move over to O’Connor, with Roy pushing from behind. Roy retrieved his weapon from O’Connor and explained that the helicopter could not get any closer because of the trees. “You’re going to have to crawl,” he said, then crouched low, turned his back on O’Connor and Tuan, and returned to Wright’s body, where he dropped to his knees. He was determined to bring Leroy back to his wife and his two boys, whose drawings he had seen taped to his locker at Ho Ngoc Tao, with the word Daddy scribbled in crayon at the top.

Tears were rolling down his cheeks, Roy realized, but there was no time to mourn—the pitch of Greyhound One’s engine was already getting higher, screaming as it hovered impatiently. O’Connor and Tuan were almost to the slick’s door, and a CIDG reached out to help them aboard. Roy worked his arms under Wright’s body—prepared to drag Wright to the slick if he couldn’t lift his 200-plus pounds up onto his shoulders—when something slammed into him so hard it pitched him forward, knocking the wind out of him. A bullet, the third he had taken in the half hour he’d been on the ground, had entered his back, exiting beneath his left armpit.

There was a heat that came with the impact, as though he’d been touched by fire, run through by a red-hot spear that ignited his insides. And then, the explosion.

ON GREYHOUND Two’s second pass across the PZ, Ewing’s door gunners expended the rest of their ammunition. Greyhound One was still hovering beside the thicket. The green uniforms of the enemy speckled the woods around the clearing, their numbers increasing by the minute.

“Mac, come on, man, you’ve been down too long!” Ewing said over the radio.

“Larry, get the hell out of there!” Yurman cut in.

As calmly as if he were picking up some buddies to go to a movie, McKibben replied, “Yeah, they’re just getting them on board now. Be done in a minute…”

Tornow had dropped in altitude and was in a wide observation bank, putting his binoculars to his eyes periodically to monitor the extraction, when he saw an NVA soldier run out from the tree line and unload his AK-47 into Greyhound One’s cockpit. He watched helplessly as Greyhound One “spun awkwardly…almost in slow motion…the blades slicing the trees, and in a moment it lay in a twisted shambles on the ground.”

Greyhound Two had banked out over the jungle for another pass, and Ewing was contemplating whether he should hover directly on top of Greyhound One to draw fire when he heard McKibben key his mic and expel a soft groan, almost like an exhale.

“Mac! Mac! You okay?!” asked Ewing, streaking back over the clearing. He saw the wreckage at once, the dust still hanging in the air, and he knew that his friend and wingman, Larry McKibben, was dead.

Oh God Oh God Oh God, what happened? he thought. Did my hesitation kill him? Oh, please no! I was going in! I swear I was going in! He cut me off. Oh, Larry, man, f—k! I’m sorry! I’m sorry! It should have been me!

A MOMENT before, Tornow had been cautiously hopeful that his twelve men, dead and alive, were coming home. Now he was hit with the despair of having both the Special Forces team and a slick crew trapped in the PZ, with the enemy emerging from the trees all around. The main body of the slick was nosed over on its right side, the tail boom broken and separated from the fuselage, lying in the grass. Bodies were dumped out on the ground beside the wreckage, the wounded attempting to crawl away. Through his binoculars, Tornow could see McKibben was slumped in his seat, motionless.

Yurman watched Greyhound Two making a slow, low pass over the clearing and knew his door gunners were unloading on the NVA in the open. He would not allow another helicopter to be shot down.

“Do not attempt extraction, Greyhound Two,” Yurman ordered Ewing. Greyhound Two’s gunners reported they were out of ammo; the helicopter’s fuel was nearly at bingo. Turning the slick’s nose east, Ewing gained altitude and headed back to Quan Loi to rearm and refuel.

“Mac, you copying this?” Yurman continued to radio. “Anybody on Greyhound One, you copy?”

Tornow, too, was trying to reach anyone on the ground. He prepped his fast movers, even as he received only a long, deafening silence.

WHEN O’CONNOR came to, he heard “a steady hissing sound, like steam escaping.” Then he felt someone going through the rucksack on his back.

“Radio, radio,” said a CIDG from Mousseau’s team. Confused, O’Connor rolled over and saw the slick about ten feet away, pitched over, nearly on its side.

Roy, his face bloody, the left side of his shirt soaked with blood, was at the right door, which was angled toward the ground, pulling the crew and team members out of the crumpled rear cabin. McKibben and Fournier were dead—McKibben from a bullet to the head and severe abdominal wounds, Fournier crushed by the transmission. Some survivors were dazed and lay sprawled motionless on the grass; others rallied around Mousseau, who sat low beneath the tail boom. Meanwhile, the slick was taking so many hits from enemy fire that it sounded like a tin can at a gun range—not a good sign, given the overwhelming stink of jet fuel and burning oil.

O’Connor called out to Roy, who turned to look at him. “You okay, O’Connor?” he asked.

“I think so,” O’Connor replied.

Sending a slightly wounded CIDG in O’Connor’s direction, Roy said, “Form a perimeter.” He pointed at a slender, wispy tree beyond the front of the helicopter, growing beside a mound of earth—what was left of the anthill. Its top had been gouged off when Greyhound One’s main rotor plowed into it during the crash. They were back where they started.

“I need ammo and a weapon,” O’Connor said.

“The chopper’s gonna blow,” Roy said. “Move out! Get weapons and ammo from the dead.”

Mousseau, along with Greyhound One’s copilot, William Fernan, Bao, and another CIDG crawled away from the tail boom back to the northern thicket, while O’Connor, Tuan, and the remaining CIDG moved toward the anthill.

“O’Connor!” Roy yelled. “Do you have a radio?”

With the help of the CIDG, O’Connor was able to retrieve two emergency radios from his pack and another from Tuan’s rucksack.

THE NVA were either terrible shots or they were focusing all their efforts on the slick, because somehow Roy, Fernan, Bao, and the two CIDG were able to scavenge the dead NVA close to their original perimeter, each yielding a weapon.

Ammunition, however, was scarce. “Single shots!” Roy told them. “No auto.” He pointed out the designated field of fire each was responsible for. “Save your bullets,” he said. He crawled over to O’Connor and retrieved a radio. “I’ll come back in a few minutes. I’ll call the tac air closer.”

Taking in the scene around him, O’Connor saw that Roy had organized the remnants of a nearly destroyed recon team and slick crew “into a force to be reckoned with,” he wrote in his statement years later. “Seriously wounded, he crawled around, constantly under fire, and gave tactical orders, took charge of air support, medical aid, ammunition and…saw to it that we positioned ourselves in a way that would increase our chances of survival, inflict maximum casualties on the enemy, and secure the PZ against almost impossible odds.”

O’Connor felt the fight that had been lost in him coming back. It was Roy’s “courage, actions, words, and coolness” that did it, he would write. “He boosted our morale, giving us the will to fight and live.”

Still, they were a battered group, almost out of ammunition, and the downed helicopter was like blood in the water, emboldening the NVA to move in and finish them off.