On January 13, 1753, Etienne Broyard arrived in New Orleans from La Rochelle, a port city on the Atlantic coast of France. He was about twenty-four years old, a soldier in the French Royal Army. More than likely he’d been assigned to the Louisiana colony against his will.

In fortresses around France, soldiers attempted to mutiny when they heard they were being sent to the “wet grave” of the New World, so called because its location placed inhabitants in the path of floods and hurricanes and exposed them to a damp climate that brought on sickness and famine. The discontent of the soldiers made the trip across the ocean tense, with the officers barely able to control the men. On landing in New Orleans, the soldiers were sometimes assembled in the town square and made to watch as the most defiant among them were hanged, to discourage further disobedience.

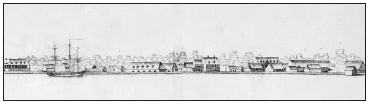

Etienne had indeed found himself in a new world. La Rochelle had a population of close to twenty thousand people and boasted a grand theater, numerous hotels and churches, taverns and shops. New Orleans was a small grid of dirt streets, nestled up against the riverbank, surrounded by swampland. Most of the buildings were simple one-story wooden houses. About three thousand people lived there—almost half of them were slaves. Etienne had probably never seen sub-Saharan Africans before. Despite La Rochelle’s position as a midway point in the triangular Atlantic trade route, slave ship holds were empty when stopping off to sell their goods on their way back to Africa.

Few people in Louisiana had come there voluntarily. Beyond a handful of Canadian fur trappers and holders of land concessions, the white colonists were mostly rejects from French society: convicts who’d been condemned to the gallows, vagabonds, and prostitutes, all deported to help populate the inhospitable outpost. To make matters worse, the Natchez and Chickasaw Indians, upset over French encroachment onto their lands, kept raiding the settlements, killing the men and taking the women and children as prisoners.

Back in 1731 the Company of the Indies, hired by the crown to colonize Louisiana, had gone bankrupt and pulled out. With their departure the slave trade into the colony temporarily dried up. The Africans who were already there were overworked and underfed and often ran away, sometimes taking their masters’ guns with them and teaming up with the local Indian tribes. In 1754 the outbreak of the French and Indian War between France and England over control of North America brought British blockades of French ships carrying desperately needed supplies.

As a soldier, Etienne fared no better than anyone else. Corrupt officials sold the food intended for the troops, leaving them with little to eat besides Indian corn, which the French considered animal feed. A French official complained to powers back home that the fighting force was often left hungry and naked. The soldiers who dared to desert risked capture by hostile Indians, who might burn them alive or scalp them. If the soldiers were caught and returned to the colony, the deserters would also almost certainly face execution.

With such desperate conditions, nobody paid much attention to segregating the races. From the very beginning, white men, confronted with a shortage of white women, had taken up with Indian women or slaves. Initially French authorities followed a policy established in Canada of encouraging mixing with native women to increase the colony’s population. Louisiana’s first priest went so far as to publicly declare that “the blood of the savages does no harm to the blood of the French,” and went around trying to get these couples to come to the church so he could marry them.

A few white men even managed to legally marry black women before the French Code Noir, or Black Code, introduced in 1724 to regulate the control of slaves and the few free blacks, put an end to the practice. It became a crime for white men to even have sexual relationships with slaves or women of color, although the many mixed-blood children whose baptismal records described them as having a “father unknown” suggest that this particular law wasn’t regularly enforced. Some of these unknown fathers eventually paid a visit to the notary public, where they acknowledged the children as their own and occasionally granted them their freedom too. Less frequently, the men emancipated the children’s mothers. Before long a new population of people began to emerge in New Orleans: blacks who had been born into freedom, who became known as les gens de couleur libre, or the free people of color.

A slave could also gain his freedom on the battlefield or for faithful service to a master or mistress. One African native, named Louis Congo, was emancipated in exchange for agreeing to serve as the colony’s official executioner. Nobody else wanted the job: it was brutal work, and Louis was always in danger of being assassinated by the friends and family of those he’d punished. Now that he was free, though, Louis could buy and sell property, marry whomever he wanted, and testify against another free person in court, just like white people. Marriage to a white person, however, was still off-limits. And he was no longer subject to the punishments outlined in the Code Noir that he was occasionally obliged to carry out—branding for first-time runaways, severing the hamstrings of those who made a second break for freedom. If a slave struck his master “so as to produce a bruise or shedding of blood in the face,” Louis was charged with executing him.

While many of Etienne’s fellow soldiers defied the Code Noir and slept with (or raped) black women, Etienne appears to have been an exception. He had barely arrived when he impregnated a young white New Orleans native named Louisa Buquoy. Louisa’s mother’s family was originally from La Rochelle, which may explain this speedy conquest.

The couple married before the baby came, and went on to have ten more children over the next twenty-five years—each one promptly baptized, sometimes at all of a day old. In a city fraught with famine, flood, and frequent outbreaks of smallpox and yellow fever, Etienne and Louisa apparently were unwilling to take any chances of a dead child ending up in purgatory. Despite the difficulty of life in the territory, nine of the eleven children survived to reach adulthood and have families themselves.

In 1763 New Orleans was handed over to Spain, as part of a peace treaty brokered at the end of the French and Indian War. The French settlers, resentful of Spain’s attempts to curtail their commerce, organized a revolt and kicked out the first Spanish governor in a coup that left the colony unstable for a few years. Though Etienne was educated and had a useful trade—master carpentry, which every Broyard male in my line practiced until my father—the few notarial records I could find suggest his fortunes rose and fell through the rocky transition. At one point he had enough money to lend 10,000 livres—about $500 at the time, or $12,000 today—to an associate; at another, a surgeon to whom he owed money got a court order allowing him to intercept Etienne’s wages and collect his debt.

But Spanish rule eventually brought an influx of cash and people to Louisiana—the Acadians came down from Canada (and became Cajuns), and emigrants arrived from the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa, which were also under the Spanish crown. And Spain began importing again the slaves that settlers viewed as crucial to their economic success. By the time Etienne died, in 1791, he’d become the owner of several houses on the corner of Bourbon and Orleans streets in the French Quarter and a Negro woman named Mariana.

That the Broyards owned a slave didn’t necessarily place them among the elite of New Orleans. Mariana likely worked together with Louisa—cooking, cleaning, and caring for the children. Nevertheless, Etienne could afford to educate his children, probably at one of the local private libraries that served as schools, and they went on to marry well and become property and slave owners themselves.

The couple’s ninth child was my great-great-great-great-grandfather Henry, a name that would reappear in almost every generation of Broyards to come. He was born around 1770, which made him twenty-one when he lost his father. His mother had died a year earlier. In the eyes of the law, he and his younger sister, Emilie, were still minors, and their share of the inheritance was entrusted to custodians, who probably auctioned off the houses and Mariana. Slaves weren’t fetching very high prices at the time. The agricultural market was soft, and there were stirrings of rebellion on the neighboring French colony of St. Domingue, which was making people wary of buying unknown hands lest they carry the “infection” of revolutionary ideas.

A few years before Etienne died, a crisis in the royal finances of France sparked a general rebellion in the country against the aristocracy. In August of 1789, the revolution led to the convening of a new government body, the National Constituent Assembly, made up solely of “the People” (rather than the clergy and nobility who had been ruling). Inspired in part by the U.S. Declaration of Independence, the assembly outlined a set of principles for writing a constitution, entitled the Declaration of the Rights of Man. The document established as its guiding principles liberté, égalité, and fraternité and, more to the point, declared that “men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” As soon as the free black population in St. Domingue heard the news, they rushed representatives to Paris to demand equal citizenship. Many of them owned sugar and coffee plantations on the island, on which they paid taxes, earning them the right to vote too.

At the time about twenty-eight thousand people of color on St. Domingue had managed to gain their freedom through means similar to those used in Louisiana: by serving in the military, being freed by their master, or, most frequently, having the good or bad luck to be the mistress or child of a white man. The revolution-era French government didn’t immediately capitulate to the free blacks’ demands, but in 1792, after two slave uprisings, the government granted the freemen their request, in hopes they’d help to keep the slaves in line. Since many of the free blacks were also planters, they counted on slave labor to work the fields too. But the slave revolt was too far along to stop, and finally, on February 4, 1794, the French government voted on the question of abolishing slavery altogether.

By this time the French legislature had become even more radicalized. When a deputy announced to a packed hall that “a black man, a yellow man, are about to join this Convention in the name of the free citizens of San Domingo,” the new members entered amid cheers and applause. The black man, an ex-slave named Bellay, took to the podium to call upon the French legislators to free his brothers. When Bellay finished, a white member stood up and made this motion: “When drawing up the constitution of the French people we paid no attention to the unhappy Negroes....Let us repair the wrong—let us proclaim the liberty of the Negroes.” Every last member rose to make known his acclamation.

Back in Louisiana the Spanish governor, Esteban Rodríguez Miró, heard news of these developments and grew increasingly worried. Under Spain’s watch the colony’s population of free people of color—believed to be the principal instigators in St. Domingue—had swelled to more than eight hundred people by the early 1790s. That made them 15 percent of New Orleans’s residents, which, combined with the slaves’ 36 percent, put whites in the minority. Indeed it was Spain’s very policies that caused the great increase in the free blacks’ numbers. Bondsmen and women could purchase their own liberty through wages they’d earned by doing extra work for their masters or from hiring themselves out during the little spare time they had.

The colonial society not only tolerated the newly freed Africans but had come to depend on them so much that Louisiana would be hard-pressed to function without them. The free blacks provided much of the skilled labor—the men became carpenters and shoemakers, and the women worked as seamstresses or laundresses. Spain also relied on the free blacks for help in defending the territory and controlling the slave population. Organized into light-skinned and dark-skinned militias, these soldiers served as a wedge between the free and enslaved black populations. For the most part, though, everybody—whites, free people of color, and slaves—had been coexisting peacefully for years.

Governor Miró began introducing measures aimed at reminding the free blacks about their proper place—beneath whites. He banned them from gathering in groups, which had little effect on the men’s card games and cockfights. And he forbade the women to wear anything ornamental—no more feathers, jewels, or silks—while also requiring them to cover their hair with kerchiefs to signify their lower status. They obliged by wrapping their heads in colorful scarves, called tignons, in a style made popular among the fashionable women of Paris by Empress Josephine.

When refugees from St. Domingue started trickling into port, bringing stories about former slaves slaughtering their masters and raping their white mistresses, Miró started to clamp down on the slaves. The Africans’ tradition of gathering on Sundays in Congo Square on the edge of town to trade their wares, play their drums, and perform the dances they had danced back home now came under attack. No matter how well everyone had gotten along in the past, the revolution in St. Domingue pointed out blacks’ and whites’ inherent status as enemies.

Within months of his father’s death in 1791, my great-great-great-great-grandfather Henry became a father himself, to a little girl named Felicity. The mother was twenty-one-year-old white New Orleans native Adelaide Hardy. Although the couple went on to have four more children, they never married. At the time, lots of couples didn’t bother to get married—weddings were expensive and unnecessary to establish legitimate heirs.

After their second child, my great-great-great-grandfather Gilbert, was born, on October 11, 1795, Henry paid a visit to the notary public in town. There he recorded an official declaration that read “for the great love and affection that he professes for his natural children,” Henry Broyard donated a house to Gilbert and his sister “to have and to hold from now and always.” This act ensured that the children could inherit their father’s property even though they were illegitimate.

The ongoing political and racial tension in Louisiana gave Henry reason to put his affairs in order. In 1795 Governor Miró’s fears proved to be founded. An elaborate plot for a slave insurrection, hatched over months of secret meetings between free people of color, slaves, and white radicals, was discovered in Pointe Coupée, the outpost a hundred miles upriver where Henry’s older brother Etienne lived. Before the date set to begin the revolt arrived, some Indian women revealed the plan. Fifty-seven slaves and three local white people were found guilty of the crime of plotting revolution. The prisoners were sent to New Orleans for sentencing, bringing the threat of racial unrest closer to home for Henry.

While the condemned men waited in prison, their family and friends among the local slaves set a series of fires throughout the city. Six months earlier a massive fire, started from a prayer candle tipping over in a breeze, had torn through the streets, burning up entire blocks. The slaves hoped to create a similar state of chaos, during which the prisoners could escape. But the militia—including free black members—managed to contain the fires, and the sentences were carried out without further disruption. Twenty-three of the slaves were hanged in the town square. Their severed heads were displayed on poles along the banks of the Mississippi, all the way from Pointe Coupée to New Orleans.

In 1800 Spain, under pressure from Napoleon, with whom the country had formed an alliance, ceded Louisiana back to France in a secret treaty. Before the transfer of government took place, Napoleon turned around and sold the colony to the United States to help cover France’s debts from the war in St. Domingue. Throughout these changes in power, the intermingling between the races in the city went on as it always had, and during the American regime it even increased.

The Broyard family suffered a personal tragedy as the century drew to a close. Henry’s wife, Adelaide, gave birth to their fifth child on Christmas Day in 1799, which also happened to be Adelaide’s thirtieth birthday. She developed complications from the labor and died the following day. The Broyard children disappear from the public records for the next fifteen years. Most likely they remained with their father, who soon got married to a woman who also happened to be named Adelaide. Gilbert was only four when his real mother passed away. She had belonged to a world that was quickly disappearing.