After a few months in New Orleans, I’d gone from having no past at all on my father’s side of the family tree to uncovering 250 years of history. Where before I only thought of myself as an “American” during a college semester in Europe—and then with some reluctance because of the negative associations it invoked: loud, crass, materialistic—now the term began to actually mean something to me. I came from a line of people who had helped to settle the country, who’d arrived here under difficult circumstances and made the best of it, who had sometimes even flourished. It amazed me to realize that my family’s story paralleled much of the country’s larger narrative; to discover that we, the Broyards, were at once ordinary and emblematic.

Walking through the French Quarter, I thought of my ancestors traveling these same streets more than two centuries earlier—heading to a job with a wooden box of tools propped on one shoulder or going off to church with a gang of kids in tow. I imagined them walking along the banquettes, the plank walkways that served as sidewalks, and wading through the rivers of mud that filled the streets when it rained. I pictured my ancestors’ shoes: leather clogs or boots caked in mud or covered in dust; Etienne or Henry cleaning them the first thing when they got home, perhaps the father and son performing this chore together. And then I remembered something that I hadn’t thought of in years: my father’s own ritual of cleaning and polishing my brother’s and my shoes—his wicker basket full of brushes and tins of polish; the rags he made from lone socks and ripped T-shirts; his caution against gumming up the brush’s bristles with too much wax; the last step, when he’d have us put on our shoes and prop up each foot on a stool while he knelt on the floor. Put your hand on my shoulder, he’d say, and we’d balance ourselves as he shimmied a cloth hard and fast across the leather, teasing out a high and glossy shine.

It was strange to stumble onto this memory of my father as I strolled down the streets of New Orleans, to suddenly feel this connection from his ancestors to him to me. I began to notice other traits that had traveled down the family tree, many landing on my brother despite his scant knowledge of our father’s past. I had always thought of myself as the child that most took after my father, but Todd turned out to be the classic Broyard of the family.

We didn’t grow up attending church, nor were we even baptized, but Todd had become a Catholic when he was twenty-one. Although we’d been surrounded during childhood by artists, intellectuals, and professionals, my brother worked first as a carpenter after graduating from college and then started a business installing security systems, a career, as he proudly declared, that placed him squarely “in the trades.” In high school he began playing the harmonica; his favorite numbers were the blues. The more I learned about our history, the more it seemed as if heredity was a force as inescapable as the gravity that had pulled Newton’s apple to the ground.

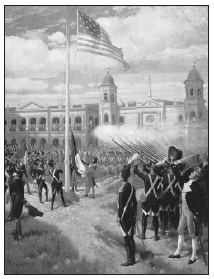

The Broyards officially became Americans on the twentieth of December in 1803, but they were still thinking of themselves as French in 1920, when my father was born. On the day of the ceremony transferring Louisiana to the United States, crowds of Frenchmen gathered in New Orleans’s town square to watch their beloved tri-color flag lowered for a final time. Men and women dressed in their finest clothes packed the balconies surrounding the square, with a select few invited to join the civic leaders in the inner chambers of City Hall.

A roll of drums accompanied the American troops as they marched into New Orleans along the riverfront. They turned into the square and came to a stop in front of the French militia—including the two black units—assembled in battle formation. The Americans were shocked by the great number of brown and black soldiers staring back at them, all with muskets in hand. The territorial commissioners, William Claiborne and General James Wilkinson, later confided that they were barely able to get through the ceremony without registering their alarm.

My great-great-great-grandfather Gilbert Broyard was seven at the time. His uncle Louis was a member of the French militia, which might have drawn his family out to watch. Also, as members of the ancienne population—the settlers who’d arrived during the first French rule—the Broyards would be stirred by the brief reappearance of their flag. The scene would have made a lasting impression on a young boy, even if the new rule didn’t have much effect on Gilbert and his family. For all of his young life, the flag of Spain had flown over New Orleans, yet everyone around him still spoke French, drank café au lait, and scanned the French paper for the latest news about the upstart general Napoleon Bonaparte overseas. It would take more than a change of colors on a flagpole to make the French of New Orleans think of themselves as anything but French.

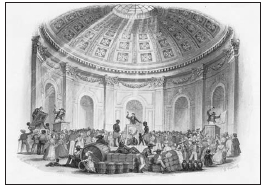

And so while the tears may have fallen freely on some faces in the crowd that day, the champagne flowed just as copiously at the ball that night. Glasses were raised to Spain, France, and the United States, and partygoers of all three nations danced, drank, and played cards together well past dawn. They weren’t stupid, after all: since the river had reopened to trade with the United States, Louisiana had more than doubled its exports in just three years. Membership in the Union could only bring greater financial gain to the aspiring merchant class.

New Orleans could stand some progress. The city hadn’t grown much in the fifty years since Etienne, the first Broyard settler, arrived. A little more than eight thousand residents were now living in New Orleans. Charleston, South Carolina, by comparison, had almost four times as many residents, according to the 1800 census. While the Spanish-style brick-and-stucco Creole town houses that replaced the old wooden one-story buildings destroyed in the fires were much more substantial, open sewers still ran down the center of many streets, and they were often clogged with garbage and the carcasses of animals. New Orleans was world famous mainly for its stench.

Watchmen went around in the evenings, lighting rows of lanterns that hung from ropes strung across the street intersections, but the blocks themselves remained in darkness, offering cover for the robbers and vagabonds who roamed about freely. At nine o’clock, the guards shut the city gates, closing in the residents for the night behind a crumbling earthen rampart that had never been effective in the first place. Most would agree that the city could tolerate some internal improvements.

The morning after the ceremony transferring Louisiana to the United States, General Wilkinson shot off a dispatch to the secretary of war calling for more troops and ammunition with the explanation that the “formidable aspect of the armed Blacks & Malattoes [sic], officered and organized, is painful and perplexing.” Claiborne sent off his own letter to James Madison at the State Department, asking for advice with his problem. He needed to commission the French militia into the American army, but if he included the colored troops, he feared objection from whites; yet if he didn’t muster them in, he feared creating “an armed enemy in the heart of the country.” Both commissioners resolved to do nothing until they heard back from Washington.

The black and mixed-race soldiers, though, were impatient for recognition. A few weeks after the change of rule, fifty of them signed a petition stating that they expected full rights of citizenship. During the transfer ceremony, they’d listened closely as Louisiana’s cession treaty was read aloud, in English and in French, and they’d heard how every inhabitant of the colony had been granted “the enjoyment of all rights, advantages, and immunities of citizens of the United States,” with no qualification about race or color. Furthermore, the soldiers reasoned, they’d fought on the American side during the American Revolution. Didn’t that count for something?

Claiborne stalled the men with the assurance that the United States wouldn’t try to take away their freedom or property. But he and the administration in Washington—who answered back with little practical advice—were both caught off guard: nowhere else in the United States had free blacks demonstrated such a sense of entitlement.

For the Louisiana planters, the unfolding drama, with free blacks agitating for equal rights, resembled events in St. Domingue too closely for comfort. The sugar crops in Louisiana were finally bringing in some profit, and the planters weren’t about to risk losing their precious slave labor, especially with all these Americans pouring into the territory, eager to grab up power and patronage for themselves. As it was, the new government was interfering with the planters’ efforts to expand their plantations. Claiborne had continued the Spanish ban on importing Africans from the French Caribbean, and the U.S. Constitution, to whose laws they were now bound, seemed to suggest that the import of foreign slaves might be outlawed altogether as early as 1808.

While Commissioner Claiborne (soon to become territorial governor) fretted over a response to the free blacks’ demands, boatloads of refugees from St. Domingue were arriving daily on Louisiana shores, keeping the specter of a slave revolt on everyone’s minds. A few weeks before the transfer ceremony, the insurgents had succeeded in overthrowing the French local government. Then on January 1, 1804, the victorious blacks in St. Domingue declared their independence. Their new nation—the first black republic in the Western Hemisphere—was called Haiti after the name given to it by its original inhabitants, the Indian natives, before the colonizers wiped them out.

A few weeks later, twelve black Haitians were spied on a boat heading up Bayou Lafourche, just west of New Orleans. In a letter to Claiborne, a white informant described the blacks’ taunting of whites on shore with stories about “eating human flesh” and “what they had been and done in the horrors of St. Domingo.” Word spread throughout the territory that the principles of liberty and equality would soon be delivered to Louisiana in an equally bloody fashion. Up in Pointe Coupée, where the blacks greatly outnumbered the whites, Henry’s brother Etienne, along with ninety-seven other men, added his name to a petition asking for more troops, saying that the slaves were showing a “spirit of Revolt and mutyny [sic].”

Troops, however, were in short supply. Claiborne resolved to ask the territorial legislature to enlist the black and colored militia’s help in controlling the slaves. After all, as in St. Domingue, many of the free men of color were slave owners themselves, and they hadn’t been asking for the emancipation of their bonded brothers, only that their own political rights be recognized. Claiborne reasoned that by treating the colored men as if they had the same concerns as whites, the state could win their loyalty. But the legislators wouldn’t stomach any action that further emboldened the free people of color. As it was, some colored planters were beginning to outstrip their white counterparts in amassing money and land. And so over the next few years, the lawmakers repeatedly ruled against the inclusion of the black and mixed-race corps in the militia and tightened the codes governing the rights of slaves and free people of color too.

Now blacks were expressly forbidden to even conceive themselves equal to whites. If they struck or insulted a white person, they faced fines or imprisonment. Free black men were restricted from emigrating to Louisiana, whether from Haiti or anywhere else. Many managed to enter the state anyway, particularly during the second migration of St. Domingue refugees at the end of 1809 and the beginning of 1810. They came from Cuba, where they’d settled after fleeing the slave revolt, but with France and Spain back at war in 1808, they’d been kicked out. These ten thousand new residents, about evenly split between whites, free people of color, and slaves, made even more difficult the execution of another new law designed to prevent free blacks from trying to pass into white society. All public records had to include an indication of racial status—with FMC for free man of color and FWC for free woman.

In 1811 the planters’ fears came to pass, with the biggest slave revolt in the history of the United States. Fifty miles upriver from New Orleans, three hundred slaves rose up, led by a free man of color from St. Domingue. The city’s free blacks saw their chance to demonstrate their solidarity with whites and rushed to volunteer their assistance to Governor Claiborne. The slaves were poorly armed and quickly put down. After the danger passed, Claiborne wrote testimonials lauding the free blacks’ patriotic conduct and again pressed for their enlistment into the militia, but the planter-legislators refused to be persuaded.

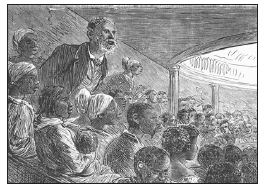

Soon, however, the United States was at war with England, and the lawmakers had no choice but to accept the colored militia’s offer of aid. At Claiborne’s urging, General Andrew Jackson, who was charged with defending New Orleans, wrote an appeal that was posted throughout town, in which he formally requested the service of free men of color in this “Glorious Struggle for National Rights.” He referred to them as “sons of freedom” and the country’s “adopted children.” He also promised the colored soldiers that they would receive the same pay, $124 in cash and 160 acres of land, as the white troops.

The speech infuriated many white Louisianans, who resented its suggestions of equality between the races. They predicted—accurately—that such treatment would encourage the free men of color to keep pressing their case for recognition. But the headstrong general had no patience for racial disputes. Over the summer, British troops had marched into Washington and torched the White House and the capitol building. Jackson couldn’t let America’s newly acquired southern port fall too.

After arriving in New Orleans in December of 1814, General Jackson immediately mustered the existing battalion of 350 men of color into the U.S. Army, and directed Colonel Joseph Savary, a free man of color who’d served in the French Republic Army in St. Domingue, to raise another unit among his countrymen. Jackson also enlisted a ragtag crew of white and black St. Domingue revolutionary insurgents led by pirate Jean Lafitte, who agreed to lend desperately needed flints and muskets to the cause. Whites also rallied to the general after witnessing his forceful speech in the town square, where Jackson had sworn to “drive their enemies into the sea, or perish in the effort.” Henry Broyard and his son Gilbert were among those who signed up.

In the early morning hours of January 8, 1815, British general Sir Edward Pakenham led an army of 8,700 veteran soldiers in a two-pronged attack that straddled the Mississippi at a point nine miles below New Orleans. Pakenham was so sure of victory that he carried on him papers appointing him as the British governor of Louisiana. But Jackson anticipated the assault and had 4,000 troops—including Lafitte’s followers and two battalions of free men of color—waiting behind some hastily erected fortifications.

The British troops advanced across the plains of Chalmette hidden in a swirl of morning fog. The wind shifted and the mist was gone, leaving the winter sun to light up the Brits’ red coats. Jackson’s forces let loose a torrent of cannon shot and rifle fire, and in less than thirty minutes the field was empty except for the masses of dead and wounded British soldiers. The day scored a decisive victory for the Americans: the British retreated and soon left Louisiana altogether. In fact a peace treaty between the two countries had already been signed in Belgium, but the news hadn’t yet made it to American shores.

The Louisiana legislators recognized the bravery of Lafitte’s men and the free men of color, noting in particular Joseph Savary’s brother, who was credited with sacrificing his own life in order to kill the British general. But the sight of so many black men walking in the streets carrying guns roused the old fears of insurrection. Perhaps bending to local pressure, Jackson gave orders for the two colored battalions to repair some fortifications outside the city. Colonel Savary answered back that his men “would always be willing to sacrifice their lives in combat in defense of their country as had been demonstrated but preferred death to the performance of work of laborers.”

Henry and Gilbert were already out at the fort, hired on as carpenters to assist with the repairs. Savary’s defiance of Jackson’s order made the Broyards’ lives difficult: they were shorthanded on laborers, and the rest of the colored soldiers began grumbling about the insult of doing this menial work. The troops began deserting the post en masse. Henry and Gilbert soon walked off the job too, in solidarity perhaps, or because they were the last ones left.

The colored veterans were granted small pensions, but they didn’t receive the land they were promised, nor the recognition that Jackson had led them to believe was their due. Every year in the parade commemorating the battle, they marched with the whites—and were even in later years granted the honor of leading the procession—but their war efforts never brought them the equal political footing they’d hoped for. Anyway, with the war over and the threat of foreign invasion gone, the pace of migration to the port city was picking up, which gave rise to a different kind of ethnic tension.

In 1817 Captain Henry M. Shreve’s new steamboat, Washington, made the round-trip journey from New Orleans to Louisville, Kentucky, in an astonishing forty-one days. A trip that once took many months of hard rowing could now be completed in relative comfort in just six weeks. More and more Americans started the journey south. Goods from across the United States followed close behind.

Parades of pine rafts, each stacked with an acre’s worth of freshly cut boards from the forests of western Pennsylvania and upper New York State, began arriving regularly at the levee. From there the wood was carted away to the various building sites springing up all over town. From Pittsburgh came more barges, these piled high with coal to heat the blast furnaces in which ironworkers fashioned the ornate balcony railings and balustrades that began appearing in New Orleans architecture in the early nineteenth century. Other flatboats, from the Midwest, arrived jammed with cattle, hogs, and horses, or barrels of flour and whiskey and sacks of corn.

Captains and merchants shouted back and forth from ship to shore, striking deals. Sailors, roustabouts, draymen, and laborers unloaded and reloaded cargo, barking orders and trading curses in half a dozen languages. Negro women wove through the crowds, selling cakes, apples, oranges, and figs from trays they balanced on their heads. Groups of slaves worked the levee too, many of whom had first come to New Orleans as yet another type of goods to be unloaded and sold.

In 1808 the United States carried through on its promise to abolish the import of slaves from foreign countries; however, a domestic slave trade developed in its place that would thrive until the Civil War. By the 1840s slave markets populated many southern cities, with the largest one in New Orleans. The traders initially concentrated their slave pens in the far end of the French Quarter, with the Americans opening a second, larger slave market in New Orleans’s central business district after the 1840s.

During the day the enslaved men might be dressed up in blue suits and top hats, and the women in long-sleeved blouses and ankle-length skirts, and made to walk back and forth on the street outside the firm’s office. Sometimes a fiddler was produced, and the slaves were commanded to dance to show off their vitality. The markets became a popular destination for tourists visiting from across the United States and from Europe.

Buyers from Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, and Mississippi purchased their field hands or house servants, blacksmiths or “fancy girls.” In the decades before the Civil War, a healthy good-sized seventeen-year-old boy cost around $1,200 (about $28,000 today), while a wealthy New Orleans man might pay as much as $5,000 ($116,000 today) for a light-skinned beauty whom he “fancied” for his own.

The increasingly profitable cotton and sugar plantations fueled the need for slave labor and provided the fortunes to buy it. During February and March, when the cotton crop was brought into town, hundreds of thousands of bales piled up on the levee and barricaded the streets until they were sold and reloaded on ships, bound for France or England or New York. All this activity meant more duties and taxes for the city and more business for nearly everyone: commission merchants, exporters, importers, banks, insurance companies, lawyers, hotelkeepers, tavern owners, shoemakers, tailors, and carpenters too, all stood to gain.

In the decade following the transfer of Louisiana to the United States, my great-great-great-great-grandfather Henry started to acquire slaves. There were two male African natives in their early twenties, who probably assisted on carpentry jobs, and a thirty-year-old black woman, who likely helped Henry’s wife with the cooking, cleaning, and care of Gilbert and his siblings. No details of these peoples’ lives exist beyond the records of their purchase and sale, so I don’t know whether Henry was kind or cruel to his human property.

While New Orleans natives such as Henry welcomed the increased opportunity brought by American rule, the newcomers’ attempts to impose their own lifestyle and values set off a culture war that would eventually divide the city. Part of the problem was that the two populations shared so little common ground. New Orleans natives spoke French, worshipped in the Catholic Church, bet on cockfights and cards (even on Sundays), and favored a spicy cuisine full of Spanish and Indian influences and cooked with methods that the slaves brought over from Africa. The Americans, on the other hand, had Anglo-Saxon roots, spoke the Queen’s English, were Protestants, frowned on gambling—especially on the Sabbath—and liked their food boiled and bland. Also, New Orleanians were far more casual than the Americans with their slaves and the local free people of color—appearing in town with their colored mistresses and illegitimate colored children, which the Yankees pointed to as ultimate proof of the moral bankruptcy of the Latin race.

For their part, New Orleans natives bristled at the hypocrisy of the Protestant ministers’ sermons railing against their pastimes when half the churchs’ parishioners had been enjoying those same pleasures twelve hours before. They referred to the northerners as “Yankee Buzzards” and griped that they were only drawn to the port city by their get-rich-quick schemes. More practically, the natives also recognized that in the contest for city rule, the Americans, with their experience in democratic government, held the upper hand.

In trying to distinguish themselves from the arrivistes, the New Orleans natives began referring to themselves as Creoles. Previously the term had been mostly used as an adjective to differentiate between native and nonnative born, but now it became a catch-all description for the ancienne population and St. Domingue refugees, both black and white. It wasn’t until American mores, including their racial attitudes, prevailed after Reconstruction that the white Creole population began insisting that it had always applied only to themselves, lest the Yankees doubt their racial purity. The ubiquity of plaçage relationships (a formalized mistress or common-law relationship) between white men and women of color gave the Americans reason to wonder about the Creoles’ blood.

Shortly after the Louisiana Purchase, marriage between the races had been outlawed, making such unions null and void. In 1828 the legislators changed the state’s civil code so that illegitimate children could no longer inherit from their fathers—even in cases where paternity had been officially recognized before a notary. At the same time, the New Orleans city council began to ban the attendance of whites at the “quadroon balls,” where many plaçage relationships were initiated. But threats of fines and imprisonment couldn’t keep the white men—Yankee and Creole alike—from searching out these nightly affairs. For male visitors to New Orleans, a trip to a quadroon ball was as customary as a tour of the slave pens and a stroll along the pier.

The most elegant of the balls were held at the St. Phillips Theater, off Bourbon Street, or the Globe, just outside the French Quarter. On most evenings white balls were held too, and men would leave one, meet up in the street to swap tickets, and then go to the other. When they recounted the dances later in their diaries or in letters to friends, they often commented on the superiority of the colored events: their finer furnishings and better orchestras, the exceptional poise and propriety of the young women in attendance.

At the St. Phillips Theater, three immense cut-glass chandeliers flooded the ballroom with light. The finest liquors lined the bar at one end of the room, and on the other end, one of the best orchestras in town accompanied the lines of quadrilles and rounds of waltzes. The women wore long gowns, and masks to cover their faces. Some of them had fair hair and pale skin, while others were almost as dark as Africans. The men disguised themselves too, dressed as young Turks or Peruvian Indians. In between dances and polite conversation, the men and women sized each other up as potential companions, and outside on the balcony or in the courtyard, under the cover of shadows, the couples appraised each other more frankly.

Among the wealthiest white men and most desirable young women, courtship involved a negotiation with the girl’s mother. She’d question the suitor about his net worth and business affairs to ensure that he could support her daughter adequately. They’d set an annuity amount, $2,000 perhaps, that he’d have to pay if he should ever leave her. Usually the man then bought or rented his mistress a little cottage on the edge of town. While her new home was being readied, the girl’s friends would fuss around her with all the same excitement as if she were having a church wedding. Sometimes the couple even lived together as man and wife; other times the man divided his time between his colored mistress and a white wife.

As the two branches of the family went on to have children themselves, all bearing the same last name, it became increasingly difficult to remember who among the dark-eyed, dark-haired children carried the taint of Africa and who did not. Indeed the siblings often knew each other—if the colored children became orphaned, it was not unheard of for the white wife to take them in. In my great-great-great-grandfather Gilbert’s case, the opposite seems to have been true: his colored “wife” and their children took in his white son, my great-great-grandfather.

Gilbert was the first white Broyard I discovered who was romantically involved with a woman of color. In the 1820 census, at the age of twenty-five, he was living with a young free woman of color, and ten years later, his house was full of children: two girls and two boys, all free blacks. The nature of Gilbert’s relationship to these people—who are not described in the records beyond their racial status and approximate age—isn’t clear. He may have been a tenant in the house; many free women of color took in boarders. Yet if that were true, his landlady’s name should have appeared as the head of the household rather than Gilbert’s. More likely he had taken a colored mistress.

Just as Gilbert entered his teenage years, the city’s streets had filled with the daughters of the St. Domingue refugees. Many of these girls owed their freedom to the beauty of their mothers or grandmothers, which had caught the eye of their slave masters, and the young women carried this cursed legacy in their own faces. Men visiting New Orleans likened the mixed-race women to sirens. One Englishman waxed on about their “lovely countenance, full dark liquid eyes, lips of coral and teeth of pearl, long raven locks of soft and glossy hair...” At the same time, white women were in short supply: in 1820 there were twenty-three white men over the age of sixteen for every ten white women of the same age. A white man without much wealth or property would have a hard time finding a desirable mate. But while visiting a quadroon ball or strolling along the levee, even a young white carpenter like Gilbert might catch the eye of a free woman of color.

For men in Gilbert’s class, the plaçage arrangements were neither as taboo nor as formalized. Gilbert couldn’t afford to pay a hefty annuity nor buy a mistress her own home. Nevertheless, a young woman of color might opt to throw in her lot with a white man with a skilled trade. No matter his degree of success, his station would be higher than that of a man of color. And at the very least, he could lighten the stigma in her children’s skin. Also, free women of color were legally prevented from marrying whites or slaves, and they greatly outnumbered the men of their caste, leaving them few alternatives.

If the woman living with Gilbert was in fact his mistress, she got a bad deal. Gilbert never acknowledged the offspring as his own: there are no records of their baptism under his name, nor do any Broyards of their age and hue appear in the public records over the next few decades. Some of them grew up and had children themselves, no doubt. Today their descendants, who would be my fourth cousins, can only guess about the story behind this empty branch of their family tree.

Gilbert, however, was not directly responsible for the mixing of my own blood. Sometime in the 1820s, he married a white woman named Marie Panquinet. He and Marie had one son together, another Henry, my great-great-grandfather Henry Antoine Broyard, born on July 18, 1829. On his baptismal record, the boy’s status as legitimate was mentioned, establishing him as Gilbert’s sole heir, and his name too—a combination of his grandfather’s and his uncle’s—indicated his rightful place in the family line.

The people assembled at Henry’s baptism on the first of October, 1829, at St. Louis Cathedral—the various Broyards and Panquinets, along with Marie’s aunt Adelle and Gilbert’s brother Anthony, who served as godparents—surely were familiar to each other, if not old friends. The Panquinets were also members of the ancienne population. Marie’s grandfather had been the sexton at St. Louis Cathedral: he rang the church’s bells at funerals and weddings and oversaw the digging of graves at the cemetery. Marie had grown up on Bourbon Street, a few blocks away from the Broyards, on the lower end of the Quarter, where the poorer Creoles and free blacks lived. And her uncle had been in the French militia too.

Soon after Henry’s birth, Marie vanished from her son’s and husband’s lives, according to public records. It’s possible that she left over objections about her husband’s colored mistress. The writer Charles Gayarré, who lived in the city during the antebellum period, described the scene in the home of a white husband who kept a mulatto mistress: “The household peace was destroyed; there were secret tears, placid resignation, or open strife and deserved reproaches.” But in the small Catholic community, divorcing one’s husband brought about just as much social stigma as an interracial affair. A more likely explanation for Marie’s disappearance is that she simply died. Shortly after Henry was born, a cholera epidemic decimated the city’s population, leaving no record of the deaths of thousands of victims.

By the time Henry was two, Gilbert had moved on to a new mate, a free woman of color named Eulalie Urquhart, with whom he had another five children. This time the kids received their father’s last name and proper baptisms (although they still weren’t entitled to inherit his property). Even Gilbert’s white siblings seem to have accepted his colored brood, with a few of them stepping in as godparents.

The census only began enumerating the names of individuals beyond the heads of households in 1850, and so the details of Henry’s young life are few. No pictures of him remain, but his military record describes him as having a yellow complexion, yellow eyes, and dark brown hair. And he’s taller than most other Creoles of that era, reaching five feet nine inches in his adulthood. I don’t know for a fact that Henry was raised in the house with his father and his common-law wife, but it appears that Gilbert and his colored family remained an important part of my great-great-grandfather’s life. Henry also became a carpenter, and he grew up close to his father’s colored children, so much so that he asked one of his half sisters to serve as godmother when his first child was born.

Yet as intimate as Henry may have been with his father’s other family, the world was increasingly drawing distinctions between them. The slaying of more than fifty whites during an 1831 slave rebellion in Virginia led by slave Nat Turner, on top of a growing abolitionist movement up north, led to clampdowns on people of color and slaves alike. If Gilbert took his family to the opera or theater, he’d be able to sit with Henry in the first tier while Eulalie and her kids were relegated to the balcony above them. If Henry and his siblings took the new omnibus that connected the different parts of the growing city, they would have to ride in separate train cars. Eulalie’s family members couldn’t legally meet with other free black friends or relatives (to prevent them from plotting a slave revolt or the overthrow of the government). And Eulalie and her children had to carry papers at all times to prove that they were free—the implication being that the natural state of blacks was enslavement. Also, as Gilbert’s only legitimate child, Henry was the only one who could inherit his property, which further reinforced the irreconcilable differences between them.

During the 1830s, thinking among whites about the origin of racial differences began to shift as well. For centuries the subject had been a favorite for theologians, philosophers, and scientists. During antiquity, the variation in people’s looks was generally ascribed to some force outside themselves. The ancient Greeks referred to blacks as Aethiops, or Ethiopians, which translates literally into “burnt face.” To explain the population’s darker skin, the philosophers pointed to the myth of Phaëthon, in which the god of the sun, Helios, lends his sun chariot to his son, Phaëthon. The boy crashes it, burning the earth and drying up all the rivers, “and that was when...the people of Africa turned black, since the blood was driven by that fierce heat to the surface of their bodies.” Aristotle, considered the father of biology, credited the range in people’s appearances to the varying climates where they lived (which is much like the way contemporary evolutionary anthropologists explain what we perceive as racial differences today).

Between the second and sixth centuries, a biblical explanation for the origin of blackness emerged in theological interpretations of a story in Genesis that came to be known as the Curse of Ham. In the text Noah is angry at his son Ham for looking at him while he is lying naked in his tent, sleeping off his drunkenness. It’s actually one of Ham’s sons, Canaan, though, whom Noah punishes. The passage reads: “And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.” Future readings of the passage began to associate Noah’s curse on Ham’s son Canaan with blackness.

Proslavery forces seized on the phrase “servant of servants” to justify the enslavement of Africans. A sticking point, however, was the story’s genealogical explanation for how the world became populated. According to the Curse of Ham, blacks and whites were descended from the same family tree, making them distant cousins to each other. Then, in the eighteenth century, the Enlightenment’s movement away from religion toward science offered a resolution to this problem.

In 1774 the British historian Edward Long first advanced the “scientific” theory that blacks and whites belonged to different species, based on his observation that their offspring were generally incapable of producing children with each other. This hypothesis of “mulatto sterility”—with the very word “mulatto” invoking “mule”—gained support throughout the first half of the nineteenth century. (The large number of mixed-raced people in the country—nearly half a million by 1850, according to the federal census—many of whom were having children with each other, was conveniently ignored.) Proslavery forces in the United States began arguing that the inevitable miscegenation that would follow emancipation would lead to the extinction of mankind altogether.

For Henry, though, no matter what the world told him about the biological difference between him and his colored siblings, Eulalie’s kids were among the shrinking number of people—white or black—who shared his last name. Even though the Broyards had been in New Orleans for four generations by this time, the family had mainly produced girls. The few sons who were born either died young or failed to have sons themselves. When Henry started fathering children in the 1850s, he was the only Broyard passing on the name to appear in the city’s sacramental or civil records.

At the same time, New Orleans’s population was more than doubling, jumping from 46,000 in 1830 to over 100,000 in 1840—mostly through foreign immigrants—which helped to throw into relief all that the white and black Creole communities had in common. The city limits exploded to handle the growth, overtaking swamps here, cypress marshes there, with city improvements close behind. Stones began to cover the streets’ dirt surfaces; gas-powered lamps replaced their hanging lanterns. Luxury hotels sprang up to accommodate the many visiting businessmen, with their high domed roofs shining above the city’s skyline.

The Americans tended to concentrate upriver of Canal Street in Faubourg St. Marie, while the French and Creoles of color stayed downriver, pushing inland into the Tremé neighborhood or farther south in the Faubourg Marigny. The arriving immigrants went where they could find housing, often along the riverfront and among the lower parts of the city. A single block in the Tremé might be home to natives of Ireland, Germany, France, Cuba, St. Domingue, Pennsylvania, and Louisiana; to people who were white, black, or mulatto and worked as carpenters, cigar rollers, laborers, or seamstresses. Surrounded by all these foreign tongues and traditions, a shared language and customs could make people forget about their differences in skin tone.

In 1835 a local newspaper had predicted that within twelve years New Orleans would rival New York City as the commercial capital of the United States. But squabbles between the French and American factions in the city council hampered progress. In 1836 the state legislators agreed to divvy up New Orleans along ethnic lines into three separate municipalities, with Canal Street as the dividing line. The Americans controlled the second municipality, upriver, and the French were in charge of the first and third, downriver. Each mini-government operated its own schools, promoted its own language, and oversaw business and economic development.

The Broyards lived among other French people in the first municipality—the French Quarter and the Tremé—where race relations were more relaxed. Free colored people were making money alongside the whites during this boom time: in 1836 they had over $2.5 million worth of real estate and slaves, with an average net worth among the property owners of $3,000, or more than $56,000 in today’s dollars. This made them the richest population of free blacks in the United States, wealthier than the whites of some southern cities, and certainly better off than Henry Broyard and his father, Gilbert.

Gilbert had tried to cash in on the building boom too. In the early 1830s, he purchased at auction a lot out on Bayou St. John, in the neighborhood that ran along the busy commercial waterway leading out to Lake Pontchartrain. But Gilbert ran into bad luck—before he was able to build his house, a problem arose with the property title, and he was forced to sell the lot at the price he’d paid for it. He never purchased any property again.

When Gilbert died, in 1851, he left no estate to pass along to his son. Being the sole legal Broyard heir meant nothing for Henry in the end. At the same time, the Creole legacy was rapidly dying out. It didn’t take long for the American sector to outpace the rest of the city, with more new buildings, better-kept streets, a superior public school system, and more wealth. In the cultural tug-of-war, the Americans had been helped along by the European immigrants. They’d come to the country for a piece of the American dream, and they soon realized that all its rules were written in English.

The Americans returned the favor, pushing for the right to vote for the German and Irish immigrants, despite the fact that most of them were illiterate. The move disgusted the free colored population—many of them had been educated in Europe or by private tutors and had fortunes a hundred times that of the unskilled laborers, and yet they weren’t entitled to vote. Finally, in 1852, when the Americans felt confident that they had the upper hand, they moved to reunite New Orleans, and with that, Creole dominance—over the French sections of the city, the general culture, or anything else—was finished.