My great-great-grandfather was surrounded by the noise of revolution. It was the spring of 1848, and Henry Broyard was a young carpenter, just eighteen years old. Night after night, cannon fire disturbed the air of New Orleans, revelers paraded through the streets, shouting “Vive la République” and singing choruses of “La Marseillaise,” ecstatic crowds cheered and applauded speaker after speaker at the St. Louis Exchange. Word had just arrived from France that a group of radical republicans and members of the working class had overthrown the monarchy that had been reinstated in 1814. Between increasingly repressive laws, a recent economic crisis, and the exploitation of the poor by the Industrial Revolution, the insurgents became fed up and forced King Louis Philippe to abdicate, restoring democracy to the country once more.

For some people in New Orleans, especially people who, like Henry, were outside the merchant class, the state of affairs at home didn’t look very different from that in France. Over the previous two months, the city had been shrouded in cotton—nearly a million bales. It lined almost every inch of the levee and blocked off half their streets until it could be sold and shipped away. But the average worker would see only a tiny portion of the profits from its sale. Nor did much benefit trickle down through improved city services, especially not in the French parts of the city.

The sanitation in New Orleans was still world-famously bad. Sometimes, when the wind shifted in the afternoon, carrying the stink into the Quarter, one house after another would start closing up its doors and windows until a whole neighborhood disappeared behind shutters. There were few public schools to speak of. And epidemics of yellow fever and cholera continued unabated. As Louisiana’s planters and the businessmen who brokered their cotton grew richer, it seemed as if the man on the street just dropped lower on the socioeconomic scale.

But at the center of town, at the St. Louis Exchange, Louisiana senator Pierre Soulé took to the podium to lift up the workingmen. He singled out the laborers of France in whose “rough and bony hands” the aim of the 1789 revolution had been realized. A common workingman was invited to take the stage. “Oh how happy I am,” the laborer began, “to be able to speak in the midst of a gathering so large and so capable of appreciating the significance of the questions that I touch on and the prejudices that I fight.” The audience cheered in agreement.

The next speaker was Thomas J. Durant, the federal attorney for the Eastern District of Louisiana, who read out a drafted proclamation to send to the people of France from the residents of New Orleans. It opened with the city’s response to the French provisional government’s decree that ended slavery for good in the French territories. (In 1802, eight years after the French assembly had abolished slavery in the colonies, Napoleon had reinstated it.) “A ray of liberty has come to shed its regenerative warmth over nations long weighed down under the detested yoke of slavery,” Durant read. The next resolution applauded the French government’s second decree, granting voting rights to all men, including those of African descent who had just been freed, because, as Durant read on, “man possesses the natural and inalienable right of self-government.” And finally the citizens of New Orleans offered their praise for this renewed appreciation of the worker. The crowd shouted their approval and raised their voices in three cheers apiece for France, for the United States, and for freedom in an uproar that was said to have echoed throughout the city.

I like to imagine that at this moment Henry, as he hurrahed along with the crowd, decided that his life would be different. Perhaps he understood for the first time that his lot as a worker aligned him with the slave to some degree—both were being economically exploited. Or maybe he was just a young man swept up by a mood of rebellion. Public support for abolition or equal rights was not only unpopular in the Deep South but dangerous and illegal. Espousers of language “having a tendency to produce discontent among the free colored population, or insubordination among the slaves” could face imprisonment or death, at the courts’ discretion.

It’s possible that feelings Henry had been storing up already were vindicated by this victory for liberté, égalité, and fraternité. All his young life, he’d watched the law draw a “line of distinction” between him and his colored half siblings and he’d heard science expound about their biological differences. Yet in all likelihood, he and his father’s colored children looked alike, with the same dark hair and tawny complexions. His relatives were probably at least as educated as he was, or even more so. According to the 1850 census, 80 percent of free people of color could read and write, while Henry had only learned how to read.

Or maybe the course of Henry’s life changed simply because he fell in love. Whatever the explanation, in a few years’ time, he would meet and marry a free woman of color named Pauline Bonée. There was only one problem: intermarriage had been outlawed in 1808. And so just as hostility against free Negroes in New Orleans was reaching a boiling point, my white great-great-grandfather started passing—as black.

Up in Washington, southern senators won passage of the Fugitive Slave Act as part of the Compromise of 1850, engineered to maintain the equilibrium in the country between free and slave states. The new act, which allowed the capture of runaways on free soil, emboldened unscrupulous slave hunters, who began with increasing frequency to seize free blacks and sell them into slavery.

Solomon Northup, a black man who had been born into freedom, had been kidnapped in Washington, DC, in 1841, even before the tightening of the fugitive slave laws, and sent by ship to the New Orleans slave market, where he was sold as a field hand. Northup described his capture and life on various plantations throughout Louisiana in his autobiography, Twelve Years a Slave, which was published in 1853, one year after the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, also set partly in Louisiana.

Stowe’s melodrama pitting virtuous slaves against wicked slave catchers had become an instant success. (It would eventually outsell every other book during the nineteenth century except the Bible.) Twelve Years a Slave didn’t find as big an audience, but its “true story” aspect greatly stirred its readers. As a writer for the New York Tribune observed, “No one can contemplate the scenes which are here so naturally set forth, without a new conviction of the hideousness of the institution from which the subject of the narrative has happily escaped.”

These books and other slave narratives made the cruelties of slavery real to many northerners for the first time. Passage of the Fugitive Slave Act also meant that residents of the free states had to witness blacks being hunted down in their own backyards and were sometimes even forced to join the search posses themselves. As popular sentiment against slavery grew up north, so did hostility against free blacks down south. In New Orleans it was vexing to the proslavery forces that no matter how many articles ran in the newspapers promoting the old argument about slavery being the natural state for people of African descent, all anyone had to do was put down his paper and look around him to see that Negroes were handling freedom just fine.

Strolling along the riverfront at night were free blacks riding in fine carriages, with their wives clad in silk dresses, velvet capes, and the occasional diamond. Nelson Fouché, a free black architect and contractor, had built himself a three-story brick house with fanlight transoms, French doors, granite lintels, and turned balusters. According to the 1850 census, the tailor Philippe Leogaster owned $150,000 worth of property (more than $3.6 million today), and the cigar maker Lucien Mansion had hundreds of workers under his hire, with white people likely among them.

In 1848 Fouché, along with some other leading free black men of the city, opened the Catholic Couvent School, where their children could study English and French composition, history, rhetoric, logic, and accounting under the directorship of another colored man, Armand Lanusse. The city’s foremost intellectual of color, Lanusse was the publisher of a journal in which he and other colored writers wrote about the social issues of the day, informed by their reading of the European Romantic movement and German idealism. He had also edited a volume of poetry, Les Cenelles, whose publication in 1848 made it the first anthology of “Negro verse” in the country.

Starting in 1850, the Louisiana legislature began to pass even more laws to reduce the rights of these free blacks, and by the end of the decade, their lives were nearly as restricted as those of the slaves.

Henry Broyard’s wife, Pauline Bonée, didn’t come from the colored elite of New Orleans, but her family had prospered enough to annoy most southern slavery apologists. Pauline’s parents could afford to send her and her brother Laurent to one of the private schools for free colored children where they’d learned to read and write. Her father, Pierre, a carpenter, earned enough money in 1850 to support his wife, mother-in-law, two children, and a widowed stepdaughter and her child. And the family had achieved these trappings of middle-class comfort despite having arrived in New Orleans as refugees to a cold welcome only a few decades before.

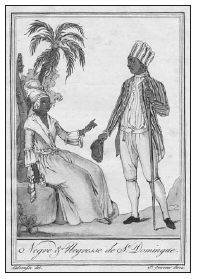

Pauline was first-generation American, born in New Orleans on January 24, 1833. Both of her parents had come to Louisiana as small children, among the St. Domingue free people of color who had fled the island’s slave revolt at the turn of the century. No specific details survive about either family’s early days in New Orleans, but their circumstances couldn’t have been easy. They’d left a homeland that had been scoured by astonishingly brutal violence—fetuses cut from living wombs and impaled on spears and people’s eyeballs yanked out with corkscrews. And these atrocities—committed by whites, free colored people, and ex-slaves alike—had come on the heels of a slavery regime so cruel that the threat of sale to St. Domingue was enough to keep slaves elsewhere in line.

By 1850 Pauline’s family had settled in the Tremé neighborhood in a two-story house on St. Ann Street, the very same block where Henry Broyard lived. And so, while my great-great-grandfather might not have spotted his future wife sitting in a tree—according to my father’s mythology—he could have spied her sitting on the second-story porch of her parents’ home.

A few years earlier, Henry had had a relationship with a different free woman of color, who gave birth to a daughter, but he hadn’t legitimized that union. If the timing of his wedding to Pauline is any indication, Henry didn’t reach the decision to marry her easily. The couple’s first son, Pierre Gilbert, was born two days after the ceremony.

The mood regarding plaçage and “living in sin” had changed since Henry’s father’s day. In his publications, the colored intellectual Lanusse often included cautionary tales in which free women of color who took up with white men came to tragic ends. He also published poems that attacked the system of plaçage, accusing mothers of prostituting their daughters out of greed. One anonymous work, titled “A New Impression,” scolded: “...a shameless mother/Today sells the heart of her grieving daughter;/And virtue is no more than a useless word which is cast aside.”

The campaign seems to have worked. By the 1850s the majority of baptisms for babies designated as free people of color occurred within wedlock. Pauline’s own parents, after living together for more than twenty years and having four children, finally consecrated their union with a wedding at St. Augustine’s in 1847. The sacramental record makes careful note that the couple’s two surviving children, Laurent and Pauline, now carried the status of legitimate, which entitled them to inherit their parents’ property.

As Henry watched Pauline’s waistline grow, the public shame awaiting her must have weighed on his mind. What did he have to lose, after all, by making the free woman of color his lawful wife? The few family members that Henry had left were mostly people of color already. The name Broyard was already tainted with blackness. He didn’t have the money, property, or standing in society to entice a white woman. Why should he consider himself too good for another carpenter’s daughter?

Because Henry was white. And no matter what else he lacked, to be white meant something in the 1850s in New Orleans. For some people it meant everything.

In early 1854, a few months before Henry and Pauline’s first child was conceived, the city’s newspapers were dominated by coverage of a trial that came to be known as the Pandelly Affair. At issue was the racial identity of a man named George Pandelly. He had recently been elected to serve on the Board of Assistant Aldermen (who were responsible for maintaining the streets and sidewalks), but a gentleman named George Wiltz had contested the election on grounds that only white men could hold public office. Pandelly, Wiltz asserted, was colored through his maternal line.

Pandelly denied the charge, maintaining that while he may have some Indian ancestors, as many white Creoles from the ancienne population did, there were no Negroes hiding in his family tree. Then Wiltz published a pamphlet to back up his claim, and Pandelly took him to court, suing for $20,000 in damages. The accusation was particularly scandalous because Pandelly’s mother was a Dimitry, sister to Alexander Dimitry, a prominent educator and leading spokesperson for the white Creole community. The New Orleans Crescent reported that one of Pandelly’s lawyers declared during opening remarks that “the [Dimitry] name would last when this trial and those concerned would be forgotten,” and then, overcome by emotion, he burst into tears.

Day after day the local papers carried testimony about the women in the Dimitry family, trying to establish their racial identity. That the maternal ancestors carried some blood other than white was quickly established: Pandelly’s great-grandmother and great-great-grandmother had been slaves during the latter part of the eighteenth century at a time when only Indians or Africans were enslaved. The question was, to which race did they belong?

The oldest residents in town were rounded up and brought to court, where a team of lawyers questioned them about the texture of the Dimitry women’s hair (crépu, or crisp, suggested African blood), the height of their foreheads (a high brow indicated Indian ancestry), and the quality of their gaze (Africans were said to have dull eyes, while the Natives’ eyes were piercing). The lawyers asked, Did whites or blacks call at their home? How did people address the women in the street: Madame—reserved for white women? Or Man—a familiar term used for colored? Where did the women attend school? In what part of the classroom did they sit?

If the trial revealed the depth of fear in the white Creole population about their racial purity, it also exposed the city’s many contradictions around race. Readers discovered, for example, that back in the 1820s, Alexander Dimitry had been thrown out of a society ball for being colored, only to be spotted a little while later dining at a local restaurant with his very accusers. Pandelly won in the end, but the case marked the beginning of a resolve within the white Creole community to divorce the notion of color from Creole for once and for all.

For Henry Broyard, though, it was too late in many ways. If his racial identity had been put to trial, he’d have had a hard time defending his whiteness. No matter what he looked like or what his ancestry actually was, he could be considered black by association. His family had worked in a colored trade for generations, he’d been seen around town with free people of color, other Broyards were known to be of mixed race, and he’d consorted with at least two women of color. Perhaps, ultimately, he didn’t care what people thought he was.

In the early winter of 1855, Henry accompanied a very pregnant Pauline to the justice of the peace, where they obtained a marriage license that described them both as “FPC,” free people of color. And then on February 12, 1855, the couple went to St. Ann’s Church, on the north end of Tremé—not St. Augustine’s, where they normally worshipped. The priest, after inspecting their license, asked the congregation if anyone knew of a reason to object to the union. With no objections coming, he blessed the nuptials before a group of witnesses, and that is what the moment of mixing in the Broyard family was like.

Henry, Pauline, and Pierre Gilbert moved into a house on St. Ann Street with one of Pauline’s half sisters and her family. The following summer, on July 21, 1856, my great-grandfather was born. (Pierre Gilbert died sometime before 1860, making my great-grandfather the oldest child in the family.) The family headed back to St. Ann’s Church, where the infant was christened Paul after his godfather, Paul Trévigne. This choice of godparent suggests how immersed Henry had already become in the colored Creole community: Trévigne was one of its most prominent members.

A writer and language instructor at the new Couvent School, Paul Trévigne embodied the principles of the colored Creoles. Born in New Orleans to free people of color of Spanish descent, Trévigne was fluent in the classical and Enlightenment traditions, strongly influenced by the republican ideals in France, and an outspoken champion of racial equality. A colleague described him as a charming blend of playfulness and poise, “with a little of the pride (the good kind) of the Castilian character.”

At the party back at the house that customarily followed christenings, Trévigne would have held forth on the news of the day. While none of the colored men could vote (nor could Henry, having forsaken this right along with his white identity), they followed local and national politics closely. Of particular interest would be the upcoming presidential election. A candidate from a new political party called the Republicans had recently entered the race, and the party’s platform gave the colored men reason to feel hopeful.

The Republican Party had been formed by a coalition of political groups united by their opposition to extending slavery into the western territories. Already the question of whether Kansas would enter the Union as slave or free had sparked bloody unrest in the state. And recently in Washington, on the floor of the Senate, Senator Charles Sumner had been beaten almost to death in retaliation for a speech he made against slavery.

Closer to home, New Orleans’s largest local paper, the Daily Picayune, had called for the expulsion of all free Negroes from the city, claiming that they were “a plague and a pest in our community, besides containing the elements of mischief to our slave population.” The white Creole paper, the New Orleans Bee, had come out in favor of the free blacks’ colonization to Liberia the year before. At the same time, the Louisiana legislature kept chipping away at the rights of people of color, most recently barring them from forming any new scientific, religious, charitable, or literary societies.

As Paul Trévigne and the other men stood outside smoking their cigars, they might have speculated about what would happen next. Forced emigration of free blacks to Africa was being debated in some of the other southern states, with a threat of reenslavement if people didn’t comply. Any conversation along these lines must have been hard for Henry to hear. It was one thing for him to voluntarily enter this circumscribed life, but he’d also hung this fate on his children.

The Democratic presidential candidate, James Buchanan, won the November election. In his inaugural address, Buchanan came out in support of “popular sovereignty,” the policy put forth by Democratic senator Stephen Douglas in the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which allowed territories to decide the slave question for themselves, thus postponing resolution of the slavery debate for the time being. But the Republicans’ respectable showing in the election—winning 38 percent of the electoral college in a field of three candidates—highlighted the growing division in the country. Then, two days after Buchanan was sworn in, the Supreme Court announced its decision in the Dred Scott case, intensifying the split even more.

The court case focused on the status of a slave named Dred Scott, who had sued for his freedom on the basis of his four-year stay on free soil. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, writing the majority opinion, held that slaves were not citizens of the United States, and therefore Scott was not entitled to sue in the federal courts. Taney also declared that blacks, free and enslaved, were “so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Furthermore, the court determined that Congress had no authority to regulate slavery in the territories, overturning the Missouri Compromise and other legislation that had maintained the balance in the country between slave and free soil. The decision greatly alarmed antislavery forces and gave the Republican Party a key issue around which to rally support.

The more threatened the southerners felt their peculiar institution to be, the more they attacked the blacks who were already free. In 1857 Louisiana governor Robert C. Wickliffe appealed to the state legislature “that immediate steps should be taken at this time to remove all the free negroes who are now in the State, when such removal can be effected without violation of the law. Their example and associations have a most pernicious effect upon our slave population.” The state lawmakers still weren’t ready to take this step—some of them had relatives who were free people of color—but they did decide to put an end to all manumissions. Slaves could no longer be freed for any reason. Also they forbade free blacks from assembling without white supervision to worship (which had been previously excluded from laws restricting their congregation), as well as banning them from running coffeehouses, billiard halls, or any establishments serving liquor, a ruling that put many colored proprietors out of business.

In 1859 the Louisiana legislature went so far as to pass an act that allowed free blacks to choose masters and voluntarily enslave themselves for life. By this time Henry and Pauline had three small children: my great-grandfather Paul, his brother, Pierre, and his sister, Pauline. Surviving family photos suggest that the kids wouldn’t have looked recognizably black, but their baptisms identified them as free people of color. If the government started to round up the free Negroes of New Orleans for expulsion or enslavement, their names would be on the list too.

Henry and Pauline’s neighbors and friends began leaving the city in droves. In early 1860 the city’s Daily Delta observed that “scarcely a week passes but a large number of free persons [of color] leave this port for Mexico or Haiti.” The Broyards, however, stayed put. Pauline’s maternal grandmother, who was living with them, was more than eighty years old, and she’d been moving all her life, from Jamaica, where she was born, to St. Domingue until the slave revolt forced her out, to Cuba until they were expelled, and finally to New Orleans. How could the family ask her to pick up and move again?

For the 1860 election, the Republicans put forward a young candidate from Illinois who had recently garnered national attention in a series of debates on the slavery question. His name was Abraham Lincoln, and his conciliatory stance—he was against slavery’s extension into the western territories, but he wasn’t calling for immediate emancipation—helped to gain him the party’s nomination. Then infighting among the opposition propelled him into the White House. By the time Lincoln was sworn in, on March 4, 1861, seven Southern states, including Louisiana, had seceded to form the Confederate States of America.

A few weeks later, Alexander Stephens, the newly elected vice president of the Confederacy, made a speech in Savannah, outlining the Southern states’ reason for secession. “Our new government is founded upon...the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and moral condition. This, our new Government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.” Then on April 12, 1861, Louisiana native General Pierre G. T. Beauregard fired on a boat bringing provisions to federal forces at Fort Sumter in South Carolina, and the Civil War began.

Almost immediately the free men of color of New Orleans, along with the white men of the city, began organizing themselves into volunteer militia units to help defend against a Yankee invasion. Among those who signed up was Henry Broyard. The colored men later explained that they’d been threatened with death or destruction of their property unless they volunteered. One man claimed that a policeman advised him to join up if he didn’t want to be hanged. But some men also volunteered with the hope of improving their position in society. Throughout Louisiana’s history, men of color had taken up arms with this aim in mind (only to be disappointed time and again). Also many free men of color owned property, which they intended to defend, no matter the moral implications. In any case, more than 80 percent of the free blacks in New Orleans were of mixed race in 1860, and they’d already been emulating white social mores for years.

The Confederate government regarded the Native Guard (as the colored troops were called) as mostly for show. The men were never given arms, uniforms, or any tactical assignments. Henry and his fellow troops did little else but parade up and down the streets in the gray coats and trousers they had purchased themselves, carrying their own antiquated muskets or walking empty-handed. But the troops made a good story for the local papers, with one predicting that the colored men would “fight the Black Republicans with as much determination and gallantry” as their white brethren.

When the time came, however, with the run of Union admiral David Farragut’s fleet past the Confederate forts guarding the mouth of the Mississippi, neither militia took a stand against the Yankees. The white soldiers fled when they heard the twelve tolls of the church bells, notifying citizens of the approaching federal forces, and the Native Guard troops were ordered by their commander to disband. They did as they were told, first hiding their muskets in buildings around the city, including the Couvent School, before returning home to their families.

Soon after Union general Benjamin F. Butler took control of New Orleans on May 1, 1862, he published an edict in the local papers, ordering the citizens to turn over any weapons. After some deliberation the Native Guard members dispatched a committee to visit Butler and offer their guns and service to the federal cause. But Butler had already contemplated using black troops and dismissed the idea, observing in a letter to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton that black men were “horrified of firearms.”

In any case, President Lincoln was hesitant to employ black soldiers for fear that arming the former slaves would push some of the border states still in the Union into siding with the South. Furthermore, Butler had read the local newspaper accounts describing the colored men’s enthusiastic response to the Confederate call to arms. Despite the Native Guard’s explanation about the coercion accompanying their previous enlistment, the general was skeptical about their loyalty to the Union. Circumstances soon forced him to change his mind.

In early August the Confederates launched an attack on Baton Rouge and were rumored to be heading for New Orleans. Butler lacked the forces for an adequate defense. He’d already enlisted all the white Unionists in the city, and Secretary of War Stanton refused his request for reinforcements, claiming they were more badly needed elsewhere. Finally the general decided to “call on Africa to intervene.” He issued a general order requesting the men of the Native Guard and the rest of the free colored population to volunteer for the Union army. Immediately the most prominent colored men of New Orleans began trying to raise companies. A fifty-three-year-old free man of color named Joseph Follin recruited men for Company C, and one of the first he signed up was Henry Broyard, age thirty-three.

Opposition to slavery played a role in motivating the enlistment of many colored men. They’d also grown up hearing romantic tales of heroism from their fathers and grandfathers who had taken up arms against the British in the War of 1812. But the men had practical considerations too—work and food were growing scarce under the war conditions. They needed the pay and rations to feed their families. Within two weeks two thousand colored men from across the city presented themselves at the Touro Building in the French Quarter to volunteer.

Still passing as black, Henry Broyard entered the regiment of the First Louisiana Native Guard as a colored corporal. When his turn came to swear in, his white appearance probably didn’t even cause the federal marshal to look twice. As a reporter for the New York Times observed, several officers in the colored regiment “were, to all superficial appearance, white men.” Butler himself claimed to Secretary of War Stanton that the darkest member of the new regiment would resemble in complexion the late senator Daniel Webster. In fact out of the ninety-five men originally enrolled in Henry’s company, twenty-six were identified as “fair, bright, yellow, or light,” while another thirty-four were described as “brown,” with the remaining thirty-five listed as “black.”

Some of those listed as black in the new regiment were runaway slaves. Despite the legal and social differences that had existed between the castes of free men and slaves, a spirit of solidarity and common cause now united them. In a letter to a new Republican newspaper, a captain in one of the regiments wrote, “In parade, you will see a thousand white bayonets gleaming in the sun, held by black, yellow, or white hands. Be informed that we have no prejudice; that we receive everyone in camp; but that the sight of human salesmen of flesh makes us sick.”

On September 27, 1862, my great-great-grandfather Henry’s regiment, the First Louisiana Native Guard Infantry, was mustered into service, becoming the first black regiment in the history of the U.S. Army. Following their enlistment, the thousand colored men marched to Camp Strong, four miles outside of town near the racetrack, to set up their tents and begin their training. The sight of these men in the dark blue coats and light blue pants of the Union uniform filled members of the local colored community with pride. They lined the streets to cheer them, and hiked out Gentilly Road to watch them drill and parade.

A few whites cheered the troops as well. The reporter from the Times praised the soldiers’ bearing and conduct. And a white officer privately complimented the colored men’s deportment in a letter: “I find them better deposed [sic] to learn, and more orderly and cleanly, both in their persons and quarters, than the whites.” The men of Henry’s company benefited from the experience of their first lieutenant, a man named Emile Detiege, who’d been schooled in military deportment by his uncle, an old Belgian who’d fought in Napoleon’s army.

But the majority of the white community, including Union soldiers, displayed their hostility for the colored troops at every turn. The Union paymaster refused to release funds for the colored troops; the supply officers neglected to fulfill requests to outfit them. The men had to scavenge their belts and knapsacks from the discards of the white units. Their commanding colonel, Spencer H. Stafford, described the regiment as “the most indifferently supplied regiment that ever went into service.”

Black soldiers returning to camp at night risked being jumped by white Union soldiers, who stripped them of their uniforms, forcing them to walk the rest of the way back in their underwear. Whites lined Canal Street during parades to shout insults at the soldiers; they turned their families out of their living quarters for late rent despite explanations about the holdup in their pay. Police officers imprisoned the soldiers’ wives and mothers on trumped-up charges and arrested members of the colored regiment at the slightest provocation.

Perhaps most insulting to the Native Guard was the whites’ constant disparagement of their fitness for military service. Even before the regiment had been officially mustered in, the Daily Picayune forecast the men’s imminent failure as soldiers because of the Negro’s “innate inferiority, natural dullness and cowardice, indolence, awe of the white man, and lack of motivation.” People on the street claimed that any three white men could send the whole regiment running with a whip and a few shouts.

For Henry Broyard, being in the Native Guard was probably the first time he experienced such prejudicial attitudes firsthand. No matter that the recent 1860 census identified him as a mulatto, he had still been walking around the world looking like and being treated as a white man. But now, as Henry marched alongside the other members of the Native Guard, the jeers of the crowd and taunts of “coward” and “damned nigger” fell on his ears too. At camp he felt the cold stares from the white soldiers. He listened to the hollow promises about the colored men’s pay that was endlessly delayed, and his family suffered because of food rations that never came. Henry learned what it meant to be black in the antebellum South by making the concerns of people of color his concerns, by joining their fight.