My great-grandfather Paul turned six the summer that his father put on the blue Union uniform and moved out to Camp Strong. For a few weeks, Paul’s father remained an intermittent presence in his life. Paul probably headed out to Gentilly Road with the rest of the free colored community to see his dad march and drill, and Henry might have come back for a home-cooked meal a few times. But at the end of October 1862, Henry’s regiment was sent out of the city for its first assignment, and Paul wouldn’t see his father again for months.

My great-grandfather was just old enough to understand that the country was at war. He might have picked up bits and pieces of news: about the holdup in his father’s pay, about the terrible conditions and rampant fever out at the camp, or about President Lincoln’s recent Emancipation Proclamation, which would free all the slaves in Confederate territories. And the day-to-day hardships that the War Between the States was imposing on the family’s life would be impossible to miss.

Food had become scarce in New Orleans and outrageously expensive, with the price of flour shooting up to $30 a barrel (equivalent to about $540 today). Henry would serve for six months before he received his first paycheck. And then his salary was short: only $7 a month, not the $13 that was promised—and was the salary paid to the white troops. But the colored soldiers had little recourse, and there was no work to be had in New Orleans either. Most trade and businesses had slowed to a halt. The levee sat quiet and deserted. The city’s streets, though, were packed with runaway slaves, all looking for work themselves.

Since the war began, slaves had been stealing away from their plantations and making a dash for Union lines. They arrived in New Orleans, sometimes as many as two hundred a day, close to starving and nearly naked. Unable to find employment or food in the city, they took to hanging around the Union camps, offering their labor in exchange for leftovers from meals.

The packs of desperate-looking Africans wandering the streets sent alarm through New Orleans’s white population. After numerous complaints, General Butler began rounding up the runaways, snatching back the freedom they’d just tasted for the first time. He placed them in refugee camps on the edge of town, where conditions were so crowded and unsanitary, especially during the summer months, that many people died.

To stem the arrival of more runaways, Butler issued an order that any Negroes caught on the street without work passes were to be seized and sent to one of the abandoned plantations taken over by the federal forces. The new pass system made it dangerous for free black people to venture onto the streets as well. Paul’s godfather, Paul Trévigne, who’d been free his entire life, was thrown into jail and had to bribe a marshal to avoid getting shipped out of town with the runaways.

Many blacks in New Orleans, free and enslaved, were beginning to realize that the presence of the Union army didn’t necessarily mean an end to their bondage and discriminatory treatment. They began to organize themselves in order to demand what they saw as their natural rights. Leading the way was Paul Trévigne.

On September 27, 1862, the same day that Henry Broyard’s regiment became the first officially sanctioned black regiment in the Union army, Trévigne put out the inaugural edition of a new French-language biweekly newspaper called L’Union. The paper was funded by a colored Creole doctor, Louis Charles Roudanez, who had been educated in France, where he’d witnessed firsthand the revolution of 1848. Trévigne as editor was an obvious choice for the doctor. They both thought of themselves as equal or superior to the average white man and resented being viewed as no better than the common slave.

In the first issue, Trévigne announced the basis of the paper’s platform as the Declaration of Independence and its founding truth that “all men are created equal.” He condemned slavery and the degradation it brought on American values, writing, “Equal rights before the law, freedom of conscience, freedom of the press, all of these things were...trampled underfoot and spat upon.” About the war he predicted swift Northern victory and the end to slavery for good. And a few months after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, Trévigne began to campaign for the black man’s right to vote. Given all the Confederate loyalists remaining in the city, Trévigne was putting himself at great risk by making public such opinions.

At just six years old, Paul Broyard wouldn’t be able to understand much of what his godfather wrote about in his paper. But I imagine that some of Paul Trévigne’s radicalism rubbed off on young Paul, because my great-grandfather grew up to agitate for equality and universal suffrage himself. Then too there was the example of his own father’s courage in battle when Henry Broyard finally got his chance to fight.

As fall stretched into winter, Henry’s regiment waited for an opportunity to prove itself. At every bivouac the men of the First Louisiana were stuck with the worst of the fatigue duty—digging latrines and unloading supplies—while the white soldiers stood around and watched. The blue uniforms that the colored men had once worn so proudly had become tattered and filthy. Tempers flared and morale sank under the steady dose of hard labor. Henry’s first lieutenant, Emile Detiége, shot and killed a new recruit for not falling into line quickly enough.

When Nathaniel P. Banks replaced Butler as commander of the Gulf, conditions worsened. While Banks wasn’t necessarily opposed to black soldiers, he certainly didn’t support them and even began demoting some after an incident in which white enlisted men refused to obey their orders. Henry’s own captain would eventually resign with the explanation that “daily events demonstrate that prejudices are so strong against colored officers, that no matter what would be their patriotism and their anxiety to fight for the flag of their native Land, they cannot do it with honor to themselves.” Even the white officers associated with the Native Guard began to suffer.

The First Louisiana’s immediate commander, Colonel Spencer H. Stafford, was a New Yorker by birth and a lawyer before the war. He frequently championed the intelligence and discipline of his colored charges, and he petitioned his superiors to ease the regiment’s fatigue assignments so the men would have time to drill for combat. Stafford knew that his soldiers were eager to prove themselves, and he believed that “when tried, they shall not be found wanting.”

Before he got the chance to lead his regiment in battle, Stafford was dismissed. After another episode of prejudice against his troops—some white sentries refused to let his men reenter the camp after collecting firewood—the colonel lost his temper and called a subordinate officer “a God damned pusillanimous, stinking white-livered Yankee.” Stafford was found guilty of “conduct unbecoming of an officer and a gentleman” and removed. Four days later his regiment shipped out for Port Hudson—without its commander—where it would face off against the Confederate forces at last.

The town of Port Hudson sat on the Mississippi River about seventy miles north of Baton Rouge. Union control of it would effectively cut the Confederacy in half, but rebels had been dug into Port Hudson for months, and a Union fleet had already been badly cut up on one attempted run past the fort. By the middle of May, though, General Banks was ready to try a simultaneous naval and infantry assault on the Confederate stronghold, with the First and Third regiments of the Louisiana Native Guard assigned a place on the extreme right of the Confederate line.

With Stafford gone the command of Henry’s regiment fell to a diehard abolitionist, Lieutenant Colonel Chauncey J. Bassett; but unfortunately for the Native Guard, overall command of the colored regiments had been given to one General William Dwight. Dwight was a drunk who resented having to be associated with the black soldiers. His interest in them didn’t seem to extend beyond abstract curiosity. In a letter to his mother, he wrote about his plans for the men in the upcoming engagement: “You may look for hard fighting, or for a complete run away....I shall compromise nothing in making this attack for I regard it as an experiment.”

It was an experiment that Dwight practically guaranteed would fail. On the morning of the assault, May 27, 1863, Dwight was drunk by the time he met with his officers. When Lieutenant Colonel Bassett asked him about the type of terrain the Native Guard would have to travel to reach the rebels, Dwight assured him that it was the easiest of all approaches into Port Hudson. In fact the general had conducted no reconnaissance; otherwise he’d have known that the colored troops would face the most difficult section of the Confederate line.

Opposing the Native Guard were six companies from the Thirty-ninth Mississippi, dug in on top of a steep bluff that overlooked the river. At the foot of this bluff was a two-hundred-yard-wide moat, eight feet in depth, that the rebels had engineered as an additional obstacle. The only approach to the position was along a road below the bluff that ran between sixty Confederate sharpshooters on one side and a battery of artillery on the other, with no cover to be found.

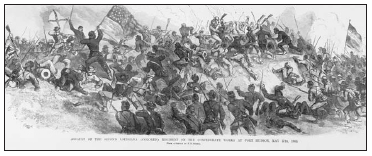

The morning of the assault was all sunshine and blue skies. After eight months of digging trenches and carting supplies, the colored troops were in high spirits as they assembled in a willow forest at the far end of the road. Henry’s company, Company C, and five other companies from the First Regiment would lead the charge. In the style of warfare of the day, the regiment lined up in two long rows in which the men would move forward in formation until they were within two hundred yards of the enemy’s position—shooting range.

At 10 a.m. Henry and the men of the First Louisiana started down the road at double-quick time. In the lead was Captain André Cailloux, a thirty-eight-year-old ex-slave. Cailloux, of unmixed African blood, liked to brag that he was “the blackest man in New Orleans.” His contemporaries described him as a “fine-looking man who presented an imposing appearance” and “a born leader.”

The Native Guard had covered about one-third of the distance toward the bluff when the Confederate artillery opened fire with a torrent of shot and shells and foot-long pieces of iron railroad. The sharpshooters began picking off the men from the left, and the two guns positioned on the river raked the right side of the line. One of the first to fall was the color sergeant—who carried the regimental banner that helped soldiers orient themselves in the fog of battle—with a shot taking off half his head.

The surprise and intensity of the slaughter sent confusion through the colored ranks. Soldiers fell back on those coming up behind them as they frantically sought cover. Cailloux had taken a musket ball in the elbow, and his left arm flopped uselessly at his side. But in his right hand the ex-slave waved his unsheathed sword, calling to his men, “En avant, mes enfants!” Forward, my children. His detachment reached the moat at the bottom of the bluff, where the colored soldiers unleashed a volley of shots upon the white men who would have them and their families enslaved.

It was the only round that the Native Guard got off. And not one of these bullets struck home. On top of the bluff, the Thirty-ninth Mississippi, in its excitement, opened fire on the black troops even before its commander had given the order to shoot. Cailloux was starting across the flooded ditch when a shell caught him in the head. Some thirty or forty of his men continued on, attempting to swim across the deep water with their muskets lifted above their heads. Nearly all of them were shot dead, with only six making it back to safety. The rest of the Native Guard had already retreated to the willow tree forest.

Out of the roughly 540 colored soldiers participating in the battle, 2 officers and 24 enlisted men were killed and another 3 officers and 92 men were wounded. Only one regiment—the 165th New York—suffered a higher percentage of casualties that day. No details of Henry Broyard’s particular experience at Port Hudson survive, but six of the fatalities came from his company, suggesting that he and the other members of his unit had been in the thick of battle.

General Banks praised the Native Guard’s performance in a letter written to his wife three days after the assault: “They fought splendidly!, splendidly! Every body is delighted that they did so well!” In his official report, Banks offered this assessment: “In many respects their conduct was heroic. No troops could be more determined or more daring....Whatever doubt may have existed heretofore...the history of this day proves conclusively...that the Government will find in this class of troops effective supporters and defenders.”

Newspapers across the country began broadcasting accounts of the Native Guard’s bravery—a good number of which were wildly exaggerated and distorted by racial stereotyping. But the New York Times observed that Banks’s report about the men’s conduct “settles the question that the negro race can fight with prowess....It is no longer possible to doubt the bravery and steadiness of the colored race, when rightly led.”

These accounts helped to change public sentiment about enlisting black troops in the Union army. Before Port Hudson the debate focused on whether arming former slaves would invite too much hostility from Southerners to be worth it. Now the Northern population measured the question in terms of the tactical advantage that the colored troops might bring to the fight. More than 180,000 colored troops would eventually serve the Union cause.

This rush of black volunteers represented a turning point in the war for the North. White enlistment had dwindled, and public support was beginning to falter in the face of the constant casualties. The influx of manpower helped to turn the mood around. The black troops freed up additional white soldiers for combat by taking over much of the guard duty and fatigue work. They also participated in a number of decisive battles themselves—the most famous among them at Fort Wagner in South Carolina.

For the country’s African American population, the participation of black soldiers and their honorable conduct in battle called forth a sense of pride that had been beaten down by slavery and race prejudice. With the possibility of freedom around the corner, the community would need leaders, and the men’s heroic conduct in war proved them up to the job. Also, the Negroes’ enlistment added strength to their political battle. If a black man was willing to die for his country, he should be entitled to the rights of citizenship. He should be allowed to vote.

Unfortunately for Henry and his fellows in the Native Guard, the elevation of their esteem in the eyes of Banks and the Northern press didn’t bring about practical improvements in their daily lives. Nowhere was this discrepancy more evident than in the treatment of their war dead. The day after the assault at Port Hudson, white flags appeared up and down the line, and the Confederates ceased their fire so that the Union soldiers could recover the fallen soldiers and bury them. Not only was this pause permitted for honorable reasons, but the stench of decaying flesh could quickly become unbearable for both sides. Yet the dead black soldiers were conspicuously denied this basic decency; their bodies were left on the battlefield to rot in the hot Louisiana sun.

Not until five weeks later, when the fall of Vicksburg forced the Confederates’ surrender, were the remains of the dead soldiers retrieved. The decomposed corpse of Captain Cailloux—identifiable only by a ring on his finger—was finally transported back to New Orleans. His funeral was the largest public event in the city since the burial for the first white Louisiana officer slain on the Confederate side. Thousands of blacks, both free and slave, lined the route from the hall where Cailloux’s body lay in state to the cemetery. As the coffin passed, borne on the shoulders of six of Cailloux’s fellow black officers, the onlookers waved small American flags.

For Paul Broyard, who turned seven that summer, the name André Cailloux would have been inescapable. The boy was perhaps even more inclined to latch onto the martyr’s story since his family had received no word of Henry’s fate. Union officials had insisted on a news blackout in New Orleans to prevent Confederate spies in the city from gaining any intelligence.

In another few months, Henry Broyard would be home to share his stories with his son firsthand. Banks continued to oppose the use of black officers, writing to President Lincoln in August of 1863 that black men were “unsuited for this duty.” One by one the officers were forced out. In late September Emile Detiége, from Henry’s company, resigned, citing prejudice as his reason, and a quarter of the men in Company C, including Henry, deserted as a result.

The soldiers were tired of facing attitudes like those held by a white lieutenant who shared this view with a newspaper reporter: “I must not only obey [a black officer], I must politely touch my cap when I approach him. I must stand while he sits, unless his captainship should condescendingly ask me to be seated. Negro soldiers are all very well, but let us have white officers, whom we can receive and treat as equals everywhere, and whom we may treat as superiors without humiliation.” In New Orleans the provost marshal under Banks likened the sight of black officers to “dogs in full dress, ready to dance in the menagerie. Would you like to obey such a fool?” But with Union victory and the beginning of Reconstruction in Louisiana, some of those “dogs” would seek to become the white men’s masters.