When Henry Broyard returned to New Orleans in October 1863 after the battle at Port Hudson, he found Paul Trévigne and the rest of his colored friends engaged in a battle of their own. President Lincoln was eager to bring the conquered Confederate territories back into the Union, a process that had been dubbed Reconstruction, and Louisiana, as the rebel state under federal control the longest, was the obvious starting place. For Lincoln the goal was to establish a state government that would be loyal to Washington as quickly as possible, but the Trévigne camp wanted to seize this opportunity to realign race relations in the South—a divisive issue that would surely cause delays.

The first step in the reconstruction process was the election of delegates to write a new state constitution. These delegates would face many thorny questions, beyond emancipating the slaves. For example, would a reconstructed Louisiana continue to enforce segregation in public spaces? Would blacks be allowed to vote? How would the economy accommodate this sudden transition from slave to free labor? And what about schools to educate the newly freed men and women? Even those whites who recognized the need for abolishing slavery weren’t prepared to accept civil and political equality for Negroes.

Paul Trévigne, however, wouldn’t settle for half measures. For him the future health of the country depended on finally honoring the Founding Fathers’ vision that all men were created equal. Using his newspaper as a platform, Trévigne helped to organize a rally in the beginning of November in support of voter registration of blacks for the upcoming election of delegates to the Constitutional Convention. The colored radicals figured they had some bargaining power. The majority of white Louisianans had supported the Confederacy; the administration in Washington could hardly now turn to these rebels to restore the Union. Since there weren’t enough white Unionists in Louisiana to make up a representative electorate, the free colored community was going to be needed for its sheer numbers.

The white Unionists at the rally finally agreed to draw up a resolution requesting the registration of blacks who were free before the rebellion to present to Louisiana’s military governor, General George F. Shepley. (They had convinced the Creoles of color that amending their original request, which included newly freed blacks too, would give the petition a better chance for success.) Elsewhere in the country, the question of Negro suffrage had barely been considered.

General Shepley never responded to the petition, and then President Lincoln disappointed the colored men too. Impatient with delays, Lincoln issued his own guidelines for the reconstruction process in early December of 1863. His plan called for the use of existing election laws, thus excluding black voters, and pardoned most Confederates, as long as they swore to uphold the U.S. Constitution and support abolition. Soon enough, Michael Hahn, a German immigrant who had been elected to Congress shortly before the war, won the gubernatorial race on a platform opposing Negro suffrage. At the same time, a labor program instituted by General Banks forced the ex-slaves back onto the plantations and sharply curtailed their movements. It was beginning to look as if reconstructed Louisiana would be indistinguishable from its antebellum days.

Trévigne helped to organize another petition, signed by one thousand colored property owners, twenty-seven veterans from the War of 1812, and twenty-two white radicals, in which the colored men’s right to citizenship was demanded on the basis of paying taxes and serving the country. Julie Hilla’s grandfather, Arnold Bertonneau, as a captain in the Union army and prosperous wine merchant, was selected, along with Jean-Baptiste Roudanez, the brother of the cofounder of Trévigne’s paper, to deliver the petition to the White House and to Congress.

Lincoln had declared his opposition to Negro suffrage during his debates with Stephen Douglas back in 1858, but his meeting with the two colored delegates from New Orleans made him reconsider the question. After hearing their case, the president explained that he could only act if the issue was “necessary to the readmission of Louisiana as a State in the Union.” (It went without saying that blacks and the ballot box weren’t exactly a unifying cause.) But Lincoln was impressed enough to pen a note to Louisiana’s Governor Hahn the following day: “I barely suggest for your private consideration whether some of the colored people may not be let in [to the franchise]—as, for instance, the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks.”

Governor Hahn ignored Lincoln’s suggestion. When the white delegates convened during the summer of 1864 to draw up Louisiana’s new constitution, they failed to grant blacks voting rights. They did establish public schools for black children but ordered their segregation from white schools. Slavery was abolished, as Lincoln’s plan required, and some radicals sneaked in a loophole that allowed the Louisiana legislature at some future date to extend suffrage to certain Negroes who had “demonstrated their capacity...by military service, taxation, or intellectual fitness.” But the end result guaranteed a two-tiered postwar society, with whites on top and the formerly and newly free blacks below them.

At the same time, General Banks began an assault on Trévigne and his colored cohorts. The general had his eye on the White House, and his success with Reconstruction, on top of his military victories, would go far in furthering his campaign. The Creoles of color’s constant agitation over suffrage was interfering with the general’s plan. Bertonneau and Roudanez’s trip to Washington had been covered extensively by the New York and Boston newspapers. The colored men’s quest for the vote had also gained support from various Northern Republicans, including influential congressmen. Louisiana’s readmission into the Union ultimately depended on the approval of Congress, and Banks wanted to prevent Trévigne and his fellow radicals from persuading their new friends in Washington to make universal suffrage a necessary condition.

By mid-July 1864, one of Banks’s lackeys had forced Trévigne’s paper into bankruptcy. Luckily L’Union’s founder was able to fund a new enterprise, the New Orleans Tribune. A white radical from Belgium, Jean Charles Houzeau, joined Trévigne as coeditor and launched an English section to reach a wider public. Contributors from Boston, Washington, and Paris began reporting from the national and international fronts. By the fall the expanded Tribune—published in the heart of the Deep South in the midst of the Civil War—became the first daily black newspaper in the United States. Copies were sent to every member of Congress.

The paper’s launch on July 21, 1864, coincided with my great-grandfather’s eighth birthday. To a boy the life-and-death crusade embodied by the newspaper must have seemed both exhilarating and frightening. Paul Trévigne bursting into the Broyard house on young Paul’s birthday, the first issue of his new platform in hand, declaring that their cause could not be stopped, would set a much different tone than the mass exodus of friends and neighbors to Haiti and Mexico just a few years before. But as the call for universal suffrage widened, uniting New Orleans’s free and newly freed Negroes with black leaders and white radicals across the country, the stakes grew even higher, with opponents of the movement willing to stop at nothing to prevent the colored men from winning the franchise.

On the evening of April 11, 1865, President Lincoln stood on the balcony of the White House and addressed a crowd of a few thousand people gathered on the lawn below him. Two days earlier General Robert E. Lee, the commander in chief of the Confederate army, had surrendered at Appomattox, effectively bringing about the end of the war. When the news reached the nation’s capital, cannon fire began booming throughout the city, rousing people from bed and shattering their windowpanes. Eventually the city’s residents made their way to the White House, where they gathered on the mansion’s lawn and called for their president to speak.

“We meet this evening,” Lincoln began, “not in sorrow, but in gladness of heart.” He took a moment to acknowledge Ulysses S. Grant, the general who had led the Union army to victory, along with his “brave soldiers”—tens of thousands of whom had died and hundreds of thousands of whom had been injured. Then the president turned to the matter of Reconstruction. “It is fraught with great difficulty,” he explained.

Indeed Louisiana’s new state government had yet to be restored to the Union, and members of Lincoln’s own party couldn’t agree about how to proceed. The radical wing of the Republicans argued that the president’s plan didn’t go far enough in restructuring the South. Thanks in part to the lobbying efforts of Trévigne and the other New Orleans Creoles of color, Congressman Thaddeus Stevens from Pennsylvania and Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts had begun to call for Negro suffrage and civil rights as a necessary condition for readmission to the Union.

In his speech that night, President Lincoln focused on Louisiana. He had consistently taken the position that the rebel states must first be returned “to their proper practical relation with the Union” before other concerns about reshaping Southern society could be addressed. Lincoln now posed for his audience: “Concede that the new government of Louisiana is only to what it should be as the egg is to the fowl, we shall sooner have the fowl by hatching the egg than by smashing it?”

But in recognition of the growing movement for universal suffrage, the president declared publicly for the first time what he had expressed in private to Louisiana’s Governor Hahn a year earlier. Regarding the vote for colored men, Lincoln told the people gathered below him, “I would myself prefer that it were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.”

For many in the crowd, this was a startling admission. And for one man standing toward the back, a militant white Southern separatist named John Wilkes Booth, it was the last straw. Booth turned to his companions and muttered, “That means nigger citizenship.” He’d been plotting to abduct Lincoln and deliver him to the Confederacy, but the war’s end was forcing him to amend his plans. Booth now swore: “That is the last speech he’ll ever make. By God, I’ll put him through.” Four days later, on April 15, 1865, Booth sneaked up on Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre, placed a pistol to the back of his head, and fired.

In New Orleans the Tribune mourned the passing of the president, who had “willingly jeopardized [his] life for the sacred cause of freedom.” Despite Lincoln’s gradualist approach to Reconstruction, his death dealt the Negro suffrage movement a severe blow.

President Andrew Johnson, like his predecessor, wanted to restore the Union as quickly as possible—a goal he thought best accomplished with as little oversight from Washington as possible. A Tennessee Democrat and former slaveholder, Johnson was disinclined to force Negro suffrage on the Southern states. Within a few months’ time, the new president’s priorities became clear when he granted amnesty to nearly all returning Confederate soldiers and officials. In November white voters across the South flocked to the polls to reinstall the rebels in the political offices they’d held before the war.

In Louisiana the Confederates swept the elections with a Democratic platform that was hardly discernible from their secessionist stance: “We hold this to be a government of white people, made and to be perpetuated for the exclusive benefit of the white race....People of African descent cannot be considered as citizens of the United States, and that there can, in no event nor under any circumstances, be any equality between the white and other races.”

Across the South and in Louisiana, black codes were instituted to allow the state to seize any freed person lacking proof of a “comfortable home and visible means of support” and hire him or her out to the highest bidder. At the same time, Louisiana lawmakers dragged their feet in establishing public schools for Negro children, despite the provision in the new state constitution requiring them to do so. As a final blow, in March of 1866 John T. Monroe, the Confederate mayor of New Orleans before the war—a man who’d been expelled from the city by Union forces for his refusal to take an oath of allegiance to the United States—was reelected to his former office.

The outlook for Southern blacks was growing bleaker by the day. For those who were already free, such as the Broyards, their standing in society was actually worse than before the war. After a century of occupying a legal and social middle ground, they were now subject to the same black codes as the ex-slaves. Most galling of all for my great-great-grandfather Henry must have been the fact that despite his having risked his life for the preservation of the Union—and belonging to the winning side—the reins of the South were now being handed over to the very men who had started the rebellion.

The colored radicals joined forces with local white Unionists, who were equally alarmed by the Confederates’ sudden return to power. Some of the Unionists came up with a plan to use a technicality as an excuse to reconvene the Constitutional Convention of 1864—the delegates had neglected to formally adjourn it—during which they could disenfranchise anyone who supported the Confederacy while at the same time granting Negroes the vote. There was concern, however, among the Tribune staff that the uncertain legality of amending the constitution would taint its validity. Beyond that, they worried that the proposed convention would incite racial violence. The planning continued without the newspaper’s support, and the organizers scheduled a meeting of the original convention delegates at the Mechanics’ Institute at noon on July 30, 1866.

Events in Washington were helping to push the matter forward. In June, Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed the rights of citizenship to all people born in the United States, regardless of their race, along with equal protection under the law. In addition the amendment barred from elected office any Confederates who had been officeholders before the war—which effectively destroyed the existing Democratic power base—while also limiting a state’s congressional representation to the percentage of eligible citizens, including blacks, it enfranchised. President Johnson submitted the amendment to the Southern states for ratification (as he was required to do), but he included a caveat advising them to reject it.

Not surprisingly, Johnson also refused to give his support to the reconvening of the Constitutional Convention in New Orleans. When an emissary from Louisiana sought his position on it, the president replied that if the local authorities needed to break up the meeting, he’d make sure the federal troops stationed in New Orleans didn’t interfere.

On the morning of July 30, 1866, about an hour before the convention was scheduled to begin, a crowd of local black families started forming outside the Mechanics’ Institute, in New Orleans’s business district. The men, women, and children had all turned out in their Sunday best. They’d heard that the conventioneers were going to give their race the vote, and they dressed up in honor of the momentous occasion. A Baptist minister, who was white, took to the steps of the hall and urged the onlookers to disperse. “You will only create more trouble by remaining here,” he told them. A half a block away, another group was gathering: rowdy white men and boys who’d begun to jeer at the black supporters as they passed by on their way to the institute. The women and children apparently heeded the minister’s request and headed home, but their men stayed on and soon had doubled their number.

Inside the Mechanics’ Institute, another two to three hundred spectators were assembled, nearly all of them black, in addition to the twenty-seven white delegates belonging to the convention. A handful of the men carried pistols or sword canes, but most had left their arms at home. The convention organizers were determined to keep the peace. They’d assured the local authorities that they wouldn’t put up a fight if the police came to break up the meeting. If trouble did start—as talk in town predicted—they were counting on the federal troops to restore order. Unbeknownst to them, the bulk of the Union force was stationed at Jackson Barracks, at least an hour’s travel time away. The commander, General Absalom Baird, mistakenly thought that the convention didn’t commence until 6 p.m. Anyway his hands were tied. President Johnson had specifically ordered him to stand down.

With the federal troops out of the way, the responsibility of peacekeeping fell to the local police force, nearly two-thirds of whom were Confederate veterans. Barely a year off the battlefield, these rebels were still smarting from their defeat and the economic hardships that came with belonging to the losing side. For their troubles they blamed “the Yankee sons of bitches” along with “the damned niggers,” and viewed the efforts to reconvene the Constitutional Convention as nothing short of insurrection.

The white press fanned the racial tension with its sensationalist coverage of black-white relations. Two days before the opening of the convention, one local paper ran a front-page story with the headline “A NEGRO ATTEMPTS TO VIOLATE A WHITE WOMAN,” despite the incident’s being three weeks old.

The police chief ordered the entire force of 499 men to report to duty on convention morning. New Orleans’s sheriff had sworn in an additional 200 deputies, also all Confederate veterans. A few officers were posted at the Mechanics’ Institute itself, with the bulk of the men held at surrounding station houses, from where they could be quickly summoned.

By midmorning about 100 policemen were lounging on the grass at Lafayette Square. Although the men were only supposed to carry nightsticks when on duty, all of them had guns, with some carrying two. When a passerby asked an officer if the men were planning on breaking up the convention, he replied, “I won’t say, but by and by we will likely have some fun.”

The heat—pushing ninety degrees by 10 a.m.—didn’t help to calm the men. Neither did the whiskey bottles that were passed around as they waited. Three hours had passed when they heard the alarm that signaled trouble—twelve taps of the fire bell, the same signal used a few years earlier to warn city residents that Union warships were heading their way.

Also out in force that morning were members of Henry Broyard’s old regiment, the First Louisiana Native Guard. Between seventy and a hundred veterans had gathered downriver to march to the Mechanics’ Institute, armed with pistols, broomsticks, even a slingshot. Three drummers and a fife player led the procession, along with a black veteran carrying a tattered American flag, reportedly the bloodstained one salvaged from the charge at Port Hudson. I don’t know whether or not my great-great-grandfather Henry was among them. The exact whereabouts on that day of Henry and of my grandfather Paul remain unknown. Their names don’t appear in any of the surviving records, and as with so many other details of my family’s past, no mention was passed down of this defining moment in Louisiana’s and the country’s history.

The trouble began when the Native Guard passed through the gauntlet of hostile whites lining Canal Street. A white boy pushed down a black marcher, yelling, “Go away, you black son of a bitch!” Blows were exchanged and a few shots were fired, but the procession managed to reach the Mechanics’ Institute, where the men were greeted with a roar of cheers. Some of the black spectators had also begun to drink in the hot sun, and their mood was growing increasingly rowdy.

Before long the troublemaking white boy reappeared to continue his taunts. Some black men, by way of reply, began lobbing bricks from a nearby construction site. Then one black man removed his revolver and opened fire. The ensuing shooting match left one black man dead and two others lying bloody in the street. A handful of courageous policemen posted at the hall tried to intervene, but they were no match for the hostile crowd. A few minutes later, the twelve-tap alarm began to sound. The police officers, special deputies, firemen, and bands of armed white citizens who headed to the institute outnumbered the conventioneers and colored onlookers by more than five to one.

Inside the Mechanics’ Institute, the white delegates, still hoping to conduct the meeting, urged the black spectators to disperse. The onlookers began exiting the building, but they found themselves surrounded by police and the armed white citizens. Before they could head back inside, the white mob started forward, firing their guns as they came.

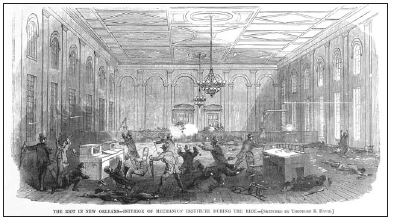

In the main hall, a white delegate took charge, commanding everyone to sit down—on chairs or on the floor—to indicate their lack of resistance. The Baptist minister moved through the crowd, telling the men to place their trust in God. The front doors were left open, in another display of submission, but when the policemen burst through the doorway, they opened fire without hesitation. Scrambling for cover, the crouching men cried out, “For God’s sake, don’t shoot....We are peaceable.”

Repeated attempts to surrender were met with more gunfire. When the minister tried to exit the institute, waving a white handkerchief atop an American flag, a policeman shot him twice, causing injuries that would end his life six days later. The remaining men inside started to fight back. With flimsy cane chairs, they tried to fend off the guns and knives of the police and the white mob. But it was hopeless. When the fighting was over, the wooden floorboards were so wet with the conventioneers’ blood that they squished underfoot.

A few white delegates managed to escape the hall and were taken into custody and protected by policemen who recognized them. Most blacks weren’t so lucky. Officers handed over black prisoners to the mob, who shot them and beat them to death. My friend Julia Hilla’s grandfather Arnold Bertonneau managed to slip out undetected and was hiding in an adjacent lot when a gang of whites discovered him. A policeman spotted Bertonneau and intervened, mistakenly thinking the light-skinned Creole of color was a white man.

When it was all over, an estimated forty-four black men had been murdered, with another forty severely wounded. On the side of the police, only one man died—a young student who accidentally stepped into the line of fire—and no men at all suffered severe wounds. The commanding officer of the Union troops, in a report to Ulysses S. Grant, came to this conclusion: “The more information I obtain of the affair...the more revolting it becomes. It was no riot; it was an absolute massacre.”

The following week a grand jury convened in New Orleans to determine the cause of the violence. None of the twenty-nine witnesses called were black or had been present inside the Mechanics’ Institute during the massacre. The all-white jury found the convention delegates and black spectators to blame for what they deemed a “riot,” and refused to charge a single policeman or white citizen for the killings. As one Unionist observer described the situation: “The rebels have control here and are determined to maintain it.”

The New Orleans massacre proved the error of President Johnson’s claim that the Southern states could be trusted to reconstruct themselves. Not only had unarmed blacks been attacked, but white men—loyal Unionists such as ex-governor Michael Hahn and R. King Cutler, who’d been elected to the U.S. Senate—were badly beaten; and other whites, such as the Baptist preacher, had died from their wounds. More practically, rebuilding the Southern states after the devastation of the war was going to require Northern investment. But with the safety of Northerners and Republicans in the South uncertain, investors were unlikely to sink their money into the region.

As the November 1866 congressional elections approached, word about the massacre spread across the country. The cover of the influential magazine Harper’s Weekly featured an illustration of the Baptist minister being fired upon while he waved a white handkerchief affixed to the American flag. A few weeks later, the American electorate—composed mostly of white Northerners—voted into Congress a two-thirds majority of Republicans, more than enough votes to override any presidential vetoes.

With the power of the House now firmly in the hands of radicals and moderate Republicans, the lawmakers soon passed the Reconstruction Acts of 1867. The bill divided the Southern states into five military districts, overseen by federal troops who would back up the authority of the local government. The act also required that every state write universal suffrage into its constitution and ratify the Fourteenth Amendment regarding citizenship as a condition to rejoining the Union.

Three years later Congress wrapped federal protection around the black man’s franchise with the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, which ensured that the “right to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” However, the wording of the amendment left open the denial of the vote on grounds of education level and property ownership, a loophole that would be exploited soon enough.

But for the moment, the reformed Southern society imagined by Paul Trévigne and his compatriots appeared tantalizingly within reach. Back in New Orleans, the radicals began calling for civil equality too—particularly the desegregation of public spaces. The Tribune commented: “All these discriminations that had slavery at the bottom have become nonsense. It behooves those who understand the new era...to show their hands, and gain the friendship of the colored population of this State.”

Pragmatic whites such as future governor Henry Clay Warmoth assessed the state’s changing political landscape, where black voters would soon outnumber whites by nearly two to one, and followed this advice. In 1868 an interracial coalition of delegates, elected by Louisiana’s first-ever multiracial electorate, headed back to Mechanics’ Institute, where they peacefully wrote Louisiana’s new constitution. The conventioneers, including Arnold Bertonneau, granted the vote to all men, except for the Confederate officeholders disfranchised by the Fourteenth Amendment, and ended segregation in schools and public places. Two years later the newly elected state legislature—more than half of whom were colored—ventured into the last bastion of equality, the bedroom, and quietly removed the ban against intermarriage that had been in place since colonial days.

After fifteen years together and the births of eight children (six of whom survived), my great-great-grandparents Henry Broyard and Pauline Bonée saw their union legally sanctioned at last. A few months later, the census enumerator came round to the Broyard house on St. Ann Street. When he was there in 1860, the enumerator had recorded everyone in the family as “mu” for mulatto. But this time Henry let it be known that he was actually white, although his wife and their six sons were mulattoes.

According to his death certificate, Henry was still a white man when he died three years later. It’s unclear whether his death from “a violent nosebleed” was sudden (resulting perhaps from a brain aneurism) or the result of a lingering illness, whether his identification as white on the certificate was his last wish or a spontaneous decision made by his wife’s nephew when reporting his uncle’s demise. Fittingly, after a lifetime of playing racial musical chairs, Henry went into the ground as a white man in the colored section of St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 on the edge of the French Quarter.

After stumbling across the location of Henry’s interment during my research, I spent a morning trying to find it, accompanied by my cousin Sharon Broyard. Sharon also lived in New York, where she worked for a financial services company, but the busyness of our lives prevented us from getting together much up north. She surprised me one June weekend in New Orleans by showing up at a genealogy conference where I was speaking about the free people of color. We decided to go look for Henry’s vault, to see if it provided any additional clues about his life.

I was also hoping to find Henry’s burial place so that he might be included in the local tradition of visiting the tombs of one’s ancestors on the first of November, All Saints’ Day. Every year, on the days leading up to the holiday, Catholics flocked to the cemetery to repair and whitewash an ancestor’s tomb, plant fresh flowers, and clean up the grounds. On the evening of All Saints’ Day, when the tombs were decorated with pots of chrysanthemums and lit with votive candles, a priest came to bless the dead.

I’d been to an All Saints’ Day celebration at a cemetery in Lacombe, a town across Lake Pontchartrain where another branch of my father’s family had lived. There, as in New Orleans, the dead were also interred aboveground. Live oak trees surrounded the small graveyard, and their twisted boughs trapped the pale glow from the candlelit tombs, forming an eerily beautiful open-air cathedral. As I moved through the ghostly light, scanning the faceplates for my family names, surrounded by other descendants of the people buried there, my connection to my dead forebears had never felt closer at hand.

My cousin Joe, the son of candid Jeanne, was already tending two other family tombs in the “black” section of St. Louis Cemetery. His parents had purchased the second one in the 1960s during a secret meeting with some family members who were living as white. Because the tomb was in the colored section of the cemetery, this family didn’t want it anymore. Joe, who works as a fireman, laughed when he told me this story. But it still bothered him that nobody was taking care of a Broyard tomb in the white part of the cemetery. Joe couldn’t because of the unspoken code that kept the white and black branches of the family from mixing. He had no better idea than Sharon or I did where exactly Henry Broyard had been buried.

The cemetery’s closing hour of noon was fast approaching. I started walking faster up and down the rows, trying to decipher the location of “tomb no. 8, left alley, facing east, upper arch.” I wasn’t sure why I’d suddenly become so anxious to find Henry’s vault. Visiting my own father’s grave generally left me feeling hollow and unsatisfied. If anything, the close proximity of his ashes just obscured my sense of him. Henry was an even more elusive character. The contradictory circumstances of his death made it impossible to finally locate him on one side or the other of the color line. I was hoping, improbably, that the wording on his vault might provide some conclusion—maybe even a reference to his race—and I would then know where the rest of the story of my mixed blood began.

Yet as I scanned the walls of vaults and rows of tombs, I was struck by the tenuousness of all these distinctions—between water and dry land in this cemetery where the dead were buried above-ground; between the blacks and whites of this city who’d been intermingling for the last three hundred years; between the legacies of the past and their consequences on the future. If dividing lines existed at all, they were conditional, temporal things.

The cemetery closed. We never managed to find Henry. Too many of the faceplates had been stolen or broken to figure out where he’d been laid to rest.