During my visit to New Orleans, Keith Medley, the proprietor of the guesthouse where I was staying, secured me some invitations to a couple of Mardi Gras balls. Tourists tend to associate Mardi Gras solely with Fat Tuesday, but Carnival season actually begins in early January, and the weeks leading up to Lent are filled with dances and parades put on by krewes and social clubs throughout the city. Both of my invites, to the Plantation Revelers and Bunch Club balls, were known particularly as Creole events.

The divisions in New Orleans’s black community had been smoothed over to some extent during the civil rights movement. Although the city’s first African American mayor, Ernest “Dutch” Morial, came from an old Creole family, neither he nor his son Marc, who succeeded him eight years later, identified as Creole. However, in some of the older customs such as the balls, the legacy of this segregated culture continued. African Americans had their favorite event too, thrown by the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club. The most well known among the black balls, Zulu generally fell on the same night as the Bunch Club dance, but tickets to the Zulu party weren’t easy to come by.

Keith had also asked our friend Bev to the Bunch Club Ball, but as the date grew closer and he didn’t reiterate his invitation, she became convinced that he didn’t really want her to go. She’d heard the rumors about the Bunch Club members employing the “paper bag test” to screen partygoers at one time, and Bev thought Keith was worried that her darker skin and dreadlocks would make her unwelcome. I tried to suggest, gently, that Bev’s insistence on constantly referring to the party as “the light-skinned nigger ball” might have given Keith the impression that she was the one who didn’t want to go. In any case, she wasn’t coming. I was worried about fitting in too, but my main concern was about what to wear.

The Bunch Club Ball required a formal gown, and the invitation for Plantation Revelers called for “Strictly Plantation Attire,” with special instructions for ladies of “no pants or skirts above the knee.” Keith offered to ask his sister, who was about my size, if I could borrow one of her gowns from a previous Mardi Gras. But the “Strictly Plantation” dress code presented more of a challenge. For starters, I wasn’t sure if that meant dressing up like the slaves or the masters.

More like slaves, suggested Keith. “You know. It’s supposed to be Saturday night on the plantation.” I wondered out loud why a group of people who neither typically descended from antebellum slaves nor seemed eager to associate with that legacy would choose a plantation theme. Keith shrugged. He had a theory that many of the more theatrical aspects of the balls and parties originated from the movies. “I bet a bunch of Creoles saw Gone with the Wind and got to thinking, ‘Now, that looks like fun! Let’s dress up like slaves on a plantation and have a hoedown!’” he said.

Keith wasn’t able to offer any more advice on the plantation attire beyond the fact that red seemed to be popular, particularly red check, and that people wore a lot of denim. “But not cowboy,” he said. “They hate cowboy outfits.” And with that, I headed off to the French Quarter to go shopping.

Since I’d been in New Orleans, I’d heard locals grumbling about Carnival—the noise, garbage, stink, and throngs of college kids who’d begun descending upon them. As Fat Tuesday drew closer, residents of the Quarter were forced to shutter the bottom-floor windows of their homes during the day to keep out unwanted guests and grease the poles that supported their balconies to prevent rabble-rousers from shimmying up to their second floors at night. Despite the hassle, however, it seemed impossible to escape the contagion of excitement in the air.

Everyone bustled around, buying beads and masks, punch bowls and party mixings, booze and outfits for all the parades and parties. They complained about being too spent, hungover, stuffed, exhausted, to attend one more thing, then went anyway, and ate and drank as much as the last time, or more. Along with a spot on a parade float or a place to watch the procession in the stands of Gallier Hall, an invitation to a Mardi Gras ball was the hottest ticket in town. I wandered in and out of stores, griping to the shop clerks about having to find outfits for two different balls, feeling just like a native.

In a costume shop on Decatur Street, I told the saleswoman that I needed something for the Plantation Revelers dance. I thought she might recognize it as a Creole affair and wonder why a white woman was going to a black party. I found myself wanting to tell her my story. Covered in tattoos and piercings, the salesclerk, who was white, looked like someone who could understand another person’s struggle over her identity. But she didn’t ask me any questions, except if there was something in particular I had in mind.

“It needs to be plantation attire,” I said. “You know, something that the slaves would wear on a Saturday night.”

The saleswoman nodded, unfazed by the potential minstrel show I’d just described, and started sorting through the racks. “What about this?” She held up a red-checked shirt.

“That could work,” I said, glancing at the tag. “Hmm, it says it’s ‘hillbilly’ style.”

The saleswomen held the shirt against me. “But it could totally go plantation,” she said. “Tie a kerchief around your head. You’re done.”

The Plantation Revelers dance was held in a convention center in Chalmette, a suburb south of New Orleans once known as David Duke territory because of its concentration of supporters for the former Ku Klux Klan leader’s 1991 gubernatorial campaign. Chalmette also had a reputation as a place where many Creole of color families had moved during the early twentieth century to pass as white. The fight in town against school integration had been particularly fierce, fueled in part by mixed families living as white who didn’t want black children with the same last names suddenly showing up as their kids’ new classmates. Yet Keith told me on the way to the dance that he’d never had a problem when he’d had a job in Chalmette.

I’d ended up in the red-checked shirt, a denim skirt (below the knee), a kerchief tied around my head, and some red tube socks, which Keith insisted were a key part of the outfit. Walking in I quickly surveyed the women in camisole tops corseted at their waists, long blue-checked skirts with aprons tied over them, and cotton shawls draped around their shoulders, and felt completely out of place. The only thing I had in common with the other women was my kerchief, although mine was red while theirs were white or blue. Keith had been right about the dance taking its inspiration from Gone with the Wind. The other women looked like sexed-up, light-skinned versions of Mammy, while I looked like somebody auditioning as an extra for Hee-Haw.

Keith gave me a sheepish smile. “You look fine, baby,” he said. (It turned out that the dance committee picked a new theme color every other year. For the last two years, it had been red; this year, it was blue. But throughout the night, I kept spotting other folks in red who also apparently hadn’t gotten the memo.)

Rows of picnic tables surrounded the dance floor, with two assigned to each party. Keith found our group and introduced me to the dozen or so men and women. “Bliss just found out she’s Creole,” he explained. “So she’s down here searching for her roots.”

They turned to me, gave me an appraising look.

I smiled, offered a little wave.

“She’s a Broyard,” Keith said.

“Oh!” Now people were nodding and smiling back. “A Broyard. Sure. I went to school with some Broyards.” They shifted around to make room. “I hope you’re hungry, bay.” A stack of plates was pushed my way. “You had any Creole cooking yet?” “Make sure you get some of them crab legs now, ’fore they’re all gone.”

Keith and I filled our plates from the spread of garlic-sautéed crab legs, jambalaya, andouille sausage, gumbo, rice and beans, spicy deviled eggs, and something called hog cheese, which I didn’t care for at all. Keith made us each a stiff rum and Coke, sharing another of his pet theories: that all the spice in the food counteracted the effect of the alcohol. I squeezed into one end of the table, next to our host, Ray. He was a tall, pot-bellied, barely tan-colored man, whose posture in his folding chair—feet planted before him, hands resting heavily on his knees—brought to mind Abraham Lincoln seated on his monument.

Ray leaned his head down to be heard above the din. “So your daddy was passablanc?”

I nodded, my mouth full of food.

“And you’re down here looking for your family?”

I smiled, nodded some more.

Ray laughed heartily and lifted his big hand to clap me on the back. “Isn’t that something?”

That was all of my story that I had to share that night. My fellow revelers could fill in the rest of the blanks themselves. We talked, drank, and ate. Then the band came on, and it was time to dance.

Plantation Revelers didn’t have a court the way some of the more formal balls did, but they held a “call out,” where the members lined up in two long rows and took turns strutting with their partners down the aisle toward a photographer who snapped their photo. I got up to head to the dance floor with the rest of the table.

“Hold on a minute, bay.” One of Ray’s daughters stopped me. “Let me fix this.” She took hold of my kerchief, which was tied in back at the nape of my neck Grateful Dead–style, and rotated it so the knot sat at my brow. “Much better.”

After the call out the band traditionally started a “second line” number. “Second line” referred to the row of stragglers who tagged along behind brass bands in parades, but it also was the name for the type of music that followed a funeral. During the procession to the cemetery for the burial, the band would play a solemn dirge, but on the trip home, the members would break into a sprightly number, with the second liners in tow, dancing and strutting, their spirits lifted by the music.

Two long notes on the trumpet announced the start of a second line number. At that cue everyone still sitting at the table hopped up and flooded the dance floor. They began waving handkerchiefs in the air, stepping up their feet as if marching in place, and snapping their fingers in time to the music.

“You look like you’ve been dancing to the second line all your life,” Keith marveled while we stomped across the floor.

I thanked him while keeping to myself the observation that it wasn’t exactly hard to keep up with this crowd. One stereotype about African Americans that I was quickly abandoning was their supposed superior dancing skill. Not only did I see plenty of people at the ball who appeared to lack natural rhythm, but the partygoers seemed on the whole as reluctant and self-conscious about getting down as attendees of most all-white affairs I’d been to. The only other song, besides the second line, that got people truly enthused was “Electric Boogie,” the theme music for the Electric Slide.

Keith likened the number to the black national anthem. Indeed there was something duty-bound about the way everyone lined up in rows and moved in unison through the dance’s steps. After four or five rounds of the same routine, I grew bored and sat down. Alone at the table, I watched my fellow revelers. Notwithstanding my inability to grasp their penchant for line dancing, I felt as if I fit right in.

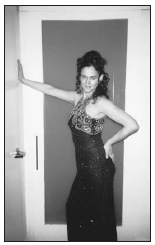

For my other Creole event, the Bunch Club Ball, I was fortunate in that I didn’t have to rely solely on Keith for fashion advice. His sister had brought by the guesthouse a big plastic crate with a dozen gowns to choose from. I selected a floor-length one made out of dark blue sequins with golden braiding crisscrossed over the bodice. It was by far the fanciest dress I’d ever worn. Then Cherry, a waitress at the Italian restaurant where I often ate, offered to style my hair for me.

Cherry was a preoperative transsexual who was training to become a beautician. The money was better than waiting tables, she said, and she was trying to save up for sex-change surgery. On the afternoon of the ball, Cherry, along with her friend Sissy, came over, bearing a big bag of styling supplies. I showed them my dress and we decided on a hairstyle.

The elaborate “Egyptian princess” updo required Cherry to curl my hair piece by piece and pin it to the top of my head. It was a slow process that left plenty of time to chat. They wanted to know about the ball and my date for the evening. During my visits to the restaurant, I’d never gotten around to telling Cherry what I was doing in New Orleans, and so I shared my story.

If anyone could understand what it was like to grow up as one thing, then realize you are something else, it was Cherry and Sissy. But it became evident as we talked that our experiences had been different. While neither of them had any doubt that they’d been born into the wrong bodies, my attachment to my blackness felt tenuous. While they weren’t waiting for anyone to give them permission to be female, I wanted someone to tell me it was okay to call myself something other than white.

For Sissy and Cherry, their external transformations were occurring in degrees—from wearing women’s clothing to taking hormones to surgically altering their bodies—but internally they’d felt themselves to be feminine for a long time. My experience was nearly the opposite. By acquiring enough knowledge about African American culture and my own Creole history, and meeting the kind of people and having the sorts of experiences that went with growing up in this community—by putting on the right clothes—I was hoping to transform myself from the outside in.

As transsexuals, Cherry and Sissy were vulnerable to ridicule or even violent attacks, but they went about undeterred from living as they felt themselves authentically to be. I remarked that it was a courageous choice, but they didn’t seem to view their lives as ruled by choice at all. “It’s who I am,” Sissy said. “It would just make things harder if I didn’t accept it.”

I, on the other hand, was hesitant to proclaim myself as part of the black community, for fear of offending someone or stepping on a racial land mine or having to field accusations of being an impostor. Just a few days earlier, when describing what had brought me to New Orleans, I’d been dismayed to hear myself backpedaling in the face of opposition once again.

I’d been at a club called Café Brasil, down the street from Keith’s place. A friend from New York, Laura, had come to visit for the weekend, and we headed out to have a few cocktails, hear some live music, and do some dancing. The place was packed. It didn’t take long after we hit the floor for two young men, both African American, to claim us as their partners.

Laura, a tall European beauty with silky black hair and striking eyes from her Chinese grandmother, was paired with the cuter of the two guys, who we soon learned was named Deforest. He was also tall, and dark and handsome, with long dreads that clouded his face and a remote demeanor (no doubt from the “blunts” he kept disappearing to smoke) that added to his sex appeal.

My guy, Edwin, was equally long and lean, but he looked sort of nerdy behind his Malcolm X horn-rimmed glasses. And he insisted on making conversation while we danced, which he seemed to think was a better mode of seduction than just keeping quiet and letting our bodies try to find some common ground.

Glancing over at Laura, I saw her and Deforest engaged in a sexy pas de deux: he was pantomiming her form, his hands held off at a respectable distance but alive and shaking at the fineness of her body. I felt jealous and thought (uncharitably) how that should really be me. Laura seemed to be enjoying herself, and she looked truly gorgeous, but she just wasn’t giving Deforest much to work with. Their dance had no dialogue to it.

Finally the band took a break, and we headed to the bar for a refill. Edwin was bursting to talk now that he could be heard. He quickly made it known that he and Deforest weren’t from New Orleans originally, saying something about the natives being a sorry collection of colored people. Edwin wondered how such a fine pair of women as ourselves had ended up at Café Brasil.

“Our friend Keith told us about it,” Laura said. “We’re staying at his guesthouse down the street.”

“In town for pleasure then?” Edwin asked, cocking an eyebrow toward me.

“I am,” Laura said, “but Bliss is here working on a book.”

“A book?” Edwin repeated, glancing at me again. Clearly books were a subject about which he had much to say. “Fiction or nonfiction?”

“Nonfiction.” I hoped that my tone would discourage further inquiries. Particularly because these guys weren’t locals, I expected that they might feel judgmental about my dad’s story. But Edwin insisted on hearing more, and Laura looked suddenly apologetic, realizing perhaps the potential awkwardness of my having to explain myself.

“Well.” I took a deep breath. “Actually you guys might find this interesting.” I launched into my spiel about how when my father passed away, I learned about a secret...“And so I came down here to find out more about my ancestry.”

Edwin shook his head, gave a little grin. He turned to Deforest, who hadn’t been paying attention, and said something I couldn’t hear. Deforest rocked back on his heels, arms crossed, and looked me up and down. It was impossible to tell what he was thinking behind his forest of locks and glassy-eyed gaze. He directed a comment my way with a lift of his chin. “So you saying you’re a sister?”

“Well, I didn’t say that I was. I said that my father was a—you know, black, or Creole, whatever.” I struggled to match the challenge of Deforest’s stare. “But if I’d been born here, I would have been considered black, legally at least.”

“What do you consider yourself?” asked Edwin.

“Biracial,” I said, trying to keep the question out of my voice.

Edwin saved me, unwittingly, by embarking on a discourse about how there was no such thing as race. “It’s a social construct with no basis in biology.” He began pontificating about the Atlantic slave trade and African essentialism.

“Right. Right,” I said. I waited for Edwin to take a breath so that I might demonstrate that I too grasped the finer points of this conversation. But the band had started again, and Deforest had moved closer to me, and I was having trouble concentrating.

Deforest stood at my left shoulder. The smell of shea butter from his dreads filled the space between us. I tried focusing again on Edwin, who was now expounding on the one-drop rule and the practice of hypodescent, designed to increase the slave population.

Deforest bent toward my ear. “I don’t believe you’re black,” he said. “I saw you on the dance floor and you don’t move like a black girl.” I turned to him, protest rising: Well, if your friend here would have just shut up for a minute....Plenty of other men, black men, have disagreed. But Deforest had moved closer still; I could feel his breath on my neck. Edwin was directing his oration—Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks—to Laura in the vacuum of my attention. “You want to prove you’re black?” whispered Deforest. “Then come home with me and let me fuck you, and we’ll see what kind of a black girl you really are.”

I jerked my head up. A smile was sneaking across Deforest’s face. I knew that he was playing with me, but his proposition also contained a real dare: Could I follow him? Could I do whatever was required to convince him of the lack of separateness between us? I knew that I couldn’t, not because he was black—by then I’d dated a few African Americans and hadn’t felt distanced by our outward differences—but I couldn’t get any sense of this guy, behind his shield of hair, smoke, and posturing. He’d unnerved me so much that I could barely muster a comeback.

“Well, that might work with some of the other Creole girls, but...”

Deforest burst into laughter, as if he’d been joking all along, then wandered off outside. With his wingman gone, Edwin seemed to lose his game and soon excused himself too. I never got around to telling Laura what Deforest had said, but she seemed to sense that my mood had shifted, and before long we called it a night.

Recalling this moment days later still sent a surge of heat roiling through me—anger mixed with anxiety and shame. I hated the image of myself in Deforest’s eyes—a silly white girl making a big fuss over nothing. I hated how uncertain I became when trying to locate myself on this racial landscape or even recognize its terrain. Torn between trying to pinpoint the boundaries between black and white and an urge to deny their existence at all, I was caught in a dialectical tug-of-war. The futility of my efforts reminded me of a skit I once saw in which a man kept moving a wooden chair around an empty white room, unable to find a spot that suited him, despite their being all the same.

I tried to explain my confusion to Cherry and Sissy. But as I heard myself voicing various complaints and objections, I imagined that I just sounded like someone mired in denial. And perhaps I was hesitant to separate myself from my white-girl roots because I feared losing some social advantage. Maybe Skip Gates had been right when we’d argued about his writing the piece about my dad: I was afraid of being stigmatized by calling myself black. Sissy, reclining on the bed, smiled benevolently as I babbled on. Stretching her arms out to her sides, she gave a big yawn. “I hear you, girl,” she said. “The whole coming out thing is really really hard.”

“All finished,” Cherry exclaimed, coming around to face me. She clasped her hands at her chest. “But wait till you see how fabulous you look! Now put on that dress and let’s take some pictures!”

There’s nothing like hamming it up for the camera, coached by two transsexuals, to make you stop taking yourself so seriously. Heading over to the party in a taxi, I got to thinking that maybe Sissy, Cherry, and the folks at the Plantation Revelers all had the right idea. Identity was a performance of sorts; I was just arriving late to rehearsal. Perhaps before Deforest turned into a Jamaican “rude boy,” he’d been a choirboy in New Jersey. Maybe Edwin picked up his racial politics at Howard after a childhood in white suburbia. Sissy and Cherry had certainly found expression for their femininity through the theatrical side of womanhood, with their interest in fashion and makeup and penchant for Sex and the City–style girl talk. We were all straddling fences of one kind or another. We were all in the process of becoming the person whom we felt ourselves most to be.

At the Bunch Ball, Keith’s services as a dance partner were in high demand, since single men seemed in short supply. I spent much of the night sitting at the table, feeling like an overlooked Cinderella. Then at the stroke of midnight, everyone started to leave in a big rush, heading off to the Zulu party, to which I hadn’t been invited.

Luckily the writer Toi Derricotte, who was in town teaching at a local university, had come too, so we could keep each other company. I’d met Toi after reading her thought-provoking memoir, The Black Notebooks, in which she explored her racial identity as a light-skinned black woman who sometimes, consciously or unconsciously, had passed as white. While I could relate to the many awkward moments in the book when someone realized Toi’s “true” identity, she wasn’t questioning what she was. She described her intermittent flights from blackness as moments of denial or experiences of being an impostor.

In conversation with Toi, I had the impression that she viewed the Creoles’ tendency to distinguish themselves from African Americans as similar rejections of their black roots. When I first came to town, that’s certainly how I saw the insistence of some relatives on calling themselves Creole rather than black or African American. Despite their explanations about the unique Creole culture and history, I still interpreted their clinging to this designation as a way to set themselves apart—and above—the rest of the African American population. To avoid accusations that I was dodging my own African heritage, I’d avoided the label of Creole myself.

Yet learning the history behind the distinct Creole of color and African American cultures in New Orleans had made it harder for me to write off someone calling himself Creole as self-hating or a bigot in denial. Certainly comments about their neighborhoods “being invaded” and the problem with “the niggers” revealed prejudice on the part of some Creoles. But to judge them solely in terms of their distance from an African American identity seemed to miss a larger point. What had brought people together at these Creole balls was more than an agreement about what they were not. Rather they were united by all they held in common: their gumbo mix of European, African, and Native American ancestries; their French language and Catholic faith; and their legacies as artisans and activists. They shared family recipes, holiday traditions, a love for storytelling. They attended the same high schools and churches. And they were united by a complex kinship in a community that, for better or worse, had been culturally, geographically, and legally segregated from both whites and African Americans for more than a century and a half. After so many intermarriages in the Creole community, everybody was to some degree cousins with everybody else.

Home has been described as the place where people understand you. The people at the Bunch Ball made sense to each other. They could even make sense of me. Being among them did make me feel at home.

Toward the end of the evening, before everyone left for the Zulu Ball, the band started up a second line number. As at the Plantation Revelers Ball, the partygoers flocked to the dance floor. Toi headed off with someone too, leaving me alone. I was debating getting up myself, when I noticed a group of women rushing toward an older man seated in a wheelchair at the table next door. “It’s your song, Grandpa,” I heard someone say. One of the women pulled the wheelchair back from the table, and everyone closed around the old man, his face lit with joy and anticipation.

The women began to clap and step their feet in time to the music. The old man raised one hand, waving the traditional napkin, and with the other rotated the wheel of his chair back and forth. Delighted by this familiar trick, the women laughed, egging the grandfather on. He swung the chair forward and backward, angling it one way and then another. One of the younger women began to wag her behind, hands on hips, and turn in circles before him. The old man thrust out his chest and gyrated his shoulders, dipping them up and down. He took the girl’s hand and twirled her.

Watching the young woman dance with her grandfather brought my own grandfather to mind. He had also been confined to a wheelchair at the end of his life. He died from bladder cancer in 1950, long before I was born, but I knew some details about his death from a few autobiographical stories that my father had written. One of them is about a son visiting his father in the hospital. His dad is seated in his wheelchair, alone in a corridor, as the narrator watches him for a moment through a small window in the door. “Throwing his head back, [Father] closes his eyes and listens again to something only he can hear. He stays like that for a while and then he opens his eyes and claps his hands. I can hear it through the door. He’s beating a rhythm, and when the chair starts to move again, I understand that he’s dancing.”

I fantasized briefly about joining the group at the next table, imagining that I’d be welcomed into their circle. They would see that I knew the joy of dancing with your family; that I understood how this atavistic pleasure could give a person a sense of her rightness in the world. But I stayed seated. When my father’s family had moved away, they’d left behind these people and their music and rituals, forfeiting my spot along the cultural continuum.

In his writings my father described his father in Brooklyn as a “displaced person.” I was beginning to understand what he meant. No one in New York could grasp the particulars of my grandfather’s life. He’d become a man without a context, which left his children adrift to chart their own courses in the world.