During the first half of the twentieth century, the blunt force of Jim Crow cut through New Orleans’s colored Creole community, scattering people on opposite sides of the color line, threatening their livelihoods, insulting their manhood, and toppling the institutions that had always sustained them. Every trip to the movie theater, beach, or opera house; every ride on the streetcar or visit to a hotel or restaurant; every stop in a public bathroom and drink from a water fountain posed the question: Was a person “colored” or “white”?

For those Creoles whose appearance made clear their black ancestry, there was no decision to make. They headed to the back of the streetcar or the balcony of the movie theater, where they sat alongside the American Negroes, who made up the majority of the city’s black population. Other Creoles who could have passed for white joined them there—people who didn’t want to abandon their friends and families or to deal with the trouble that could come from bucking the city’s color line. Over time some of these Creoles not only resigned themselves to the label of Negro, but they began taking on aspects of the lifestyle that went with it. They stopped teaching their children how to speak French. Because the public schools offered instruction exclusively in English, a new generation of Creoles grew up unable to understand what their elders were saying. On the political front, they joined forces with the American Negroes in the local chapter of the NAACP, after its opening in 1915, where they worked together to fight discrimination.

Many other colored Creoles, however, saw the bifurcation of the racial order in the city—and its elevation of a person’s blood over his culture and accomplishments—as a crude American invention. Obeying it meant conceding to the gradual effacement of their Creole identity. Already their claim to the term was threatened by the white Creole population, who since Reconstruction had been trying to redefine “Creole” as strictly Caucasian, lest the northern newcomers suspect them of being “tainted by the tarbrush.” And so many colored Creoles—rather than relinquish the sense of themselves that had fueled their self-worth over the last century—put off choosing between “white” and “colored” for as long as they could. They turned inward, to their church and clubs, to their Creole neighborhoods, and most of all to their families. In this way Jim Crow at once crystallized the colored Creole identity while also fracturing it. It encouraged Creoles to set themselves apart, where they stood proud, protected, and finally sidelined by history. The trajectory of my great-grandfather’s life—from a proud Creole businessman to a man who, in his grandson’s words, “was as shabby as shabby can be”—echoed the colored Creoles’ demise.

In the early decades of Jim Crow, Paul Broyard and his family could avoid situations where they’d be reminded of their second-class citizenship. When my grandfather Nat rode the streetcars, he might head past the white and colored sections to stand on the back platform. Or if he or his sisters went to Canal Street to go shopping, they could make sure to use the toilet at home rather than having to choose between the different public restrooms. And in Tremé or the Seventh Ward, it was pretty much business as usual. While Paul was no longer the Republican ward boss doling out treats from his goody bag of patronage, his successful construction business still earned him a respectful “Monsieur” from his neighbors.

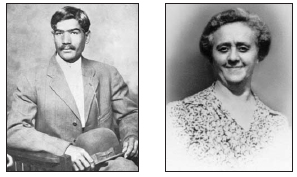

With most blacks shut out of skilled work in factories and from jobs in white-collar professions, many colored people were beginning to feel the economic sting of Jim Crow. But the Creoles of color continued to dominate the building trades, of which carpentry was considered among the most prestigious. With a construction firm and an architect’s office in town, Paul was doing better than most. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, he was regularly hired, mostly by whites, to build residential housing and rental properties, with as many as three jobs going at once. By 1905 he was able to purchase a two-story home on a nice block in Tremé, with plenty of room for his seven children.

In his house Belhomme could be assured of receiving the treatment due the man of the family, no matter how low his standing in the world might fall. My grandfather Nat, along with his two brothers, worked for the family business, while the four girls helped out with chores and tended to their father. My grandfather liked to describe for my father how on hot evenings Paul would retire to the porch, where one daughter would bathe his feet in a tin of lemon-scented water, another would wind the gramophone to play his French opera records, the third would bring him a cold drink and the paper, and the fourth would ply him with a fan.

At work Paul would have had to act respectfully to his white employers: taking off his hat in their presence, calling them “Mister.” But white people had always expected that treatment. Only one building contract out of three dozen secured by the Broyards in the two decades following the Plessy verdict stipulated that the construction be supervised by a white man. Otherwise the white men hired Paul, paid him his money, and left him alone.

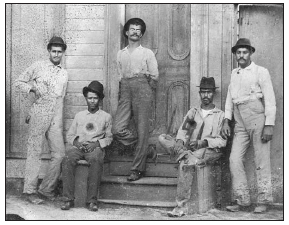

On the job site the color line worked a little differently. All the skilled workers under Paul’s hire—the carpenters, lathers, plasterers—were Creoles of color, while the laborers—the men digging foundations, sawing boards, nailing up shingling—were American blacks. The two groups didn’t mix. During lunch hour they sat apart. They headed to different water barrels when they were thirsty. Posing for a photo, Paul and his brothers stood, while the darker-skinned laborers were seated beneath them. Compared to these men, the Broyards were the bosses, the ruling class, the whites.

In oral histories collected by the historian Arthé Agnes Anthony about the Creole of color community during the early twentieth century, an interviewee recalled the Broyard family as belonging to a “high class” group of Creoles. That meant that my grandfather and his siblings grew up speaking French at home, the family’s bookshelves displayed their Francophile tastes in literature, they visited the French Opera House to hear the latest performers. And as a general rule, they didn’t socialize with darker-skinned American Negroes.

Unlike the situation in previous generations, a formal education wasn’t needed to belong to the upper crust of Creole society. Following the resegregation of public schools in 1877, many Creole families opted against sending their children to the “colored schools,” which were seen, according to another of Anthony’s interviewees, as “for the poor and those with limited backgrounds.” Yet few people could afford private schools or tutors. Many in my grandfather’s generation left the classroom after the eighth grade. In Nat’s case, rather than continue on to secondary schooling, it made more sense for him to begin apprenticing in his father’s business, given that carpentry was the best occupation available to him.

Creoles with social aspirations were also expected to conform to a certain standard of respectability. Mothers made sure their children were outfitted in clean, neatly pressed clothing, with their hair combed and shoes shined. Families were to be seen in church on Sunday. Daughters must be kept close to home until they were married, young children were expected to mind their elders, and no one in the family should ever have babies out of wedlock or engage in extramarital affairs. Families whose members began to stray might find themselves snubbed at a Creole dance or church services. They could run into difficulties when trying to court a girl from a good family or they might become the subject of gossip among the grocers at Tremé market. Many believed that by continually improving his character, the colored person might even one day convince whites of his worth in the world.

In the early days of Jim Crow, black leaders around the country were also stressing the importance of respectability. Ida B. Wells, famous for her crusade against lynching, encouraged blacks to “strive for a higher standard of social purity” through her activity in the National Association of Colored Women. Booker T. Washington suggested that African Americans, through hard work and the demonstration of their Christian virtues, would “give lie to the assertion of his enemies North and South that the Negro is the inferior of the white man.” Even the educator and activist W.E.B. Du Bois’s push for higher learning and acculturation for African Americans contained a note of moral uplift.

Still, a decade into Jim Crow, it became increasingly clear that no matter how useful to the economy or inoffensive to society southern blacks strove to be, whites weren’t going to get rid of segregation or restore universal suffrage anytime soon. They had too much economic self-interest to voluntarily concede their superior position. If anything, the separation of the races was making white prejudice more deeply entrenched. The formation of the NAACP in 1909 and the subsequent ascendance of Du Bois over Washington as the leader of the country’s black community signaled a change in tactics. Agitation, not accommodation, was the only way to win back their rights. It would take almost fifty years of fighting before the Supreme Court would finally acknowledge in the Brown v. Board of Education decision that separate status had never been equal.

By 1920 the Louisiana legislature had passed the bulk of statutes that formalized the legal wall between the black and white population in the state. Now blacks were lawfully prevented from moving into predominantly white neighborhoods. Prisons, mental institutions, and circuses too all drew the color line. In 1916 the Catholic Church segregated worshippers in downtown New Orleans with the inception of Corpus Christi, an all-black parish in the heart of the Creole Seventh Ward. Many Creoles, including my great-grandfather Paul, stopped attending services in protest.

Between the clampdown of Jim Crow laws and the stiffening of the moral code in the community, a man like Belhomme was left with little room to move. He had always lived best by living large. And the more white southerners tried to make him feel small, the bigger his personality became.

In 1915 Paul Broyard had given over his house to his oldest daughter and bought a second home on a mixed block of whites, Creoles, and a few blacks in the Seventh Ward. This house was even bigger than the first, with seven large rooms, two fireplaces, a wide arched hallway, and a side porch. Out back was a stable for his horses, above which were the servants’ quarters. The sight of these people working in the kitchen, who appeared phenotypically black compared to the nearly white-looking Broyards, helped Paul and his family to maintain their sense of occupying a middle position.

Belhomme was nearing sixty but didn’t show any signs of slowing down. For much of his adult life, he’d been known as a ladies’ man. His grandsons—including my dad—would grow up hearing stories about their grandfather’s exploits: how he liked to say that if you spread a woman’s hair on the pillow and kiss her on the lips, she will open her legs like a Bible. Or that he would head to the Tremé market with six baskets on his arms—one to fill for each of his girlfriends.

The women in the family clucked about Belhomme’s “outside children,” many of whom took the Broyard name. His son Jimmy, visiting a girl he liked across the river one day, spied a picture of Paul on her mantle. When he asked the girl why she had the photograph, she explained that the man was her daddy! Retelling the story sixty years after Paul’s death, Jimmy’s son, Jimmy Jr., laughed, explaining how his father had hightailed it out of there.

It’s hard to know what Rosa made of her husband’s adulteries. During their forty-two years of marriage, Rosa bore eleven children and likely miscarried a few more. She might have looked past Paul’s transgressions because she simply didn’t want to be pregnant anymore. But she couldn’t stop the neighbors from gossiping about Belhomme’s excesses; nor could she prevent that talk from tainting the family’s good reputation.

For Nat, having a father like Paul must have been both a badge of honor and a mark of shame. As a young man, he could either compete with his dad’s lothario behavior or reject such shenanigans completely, a choice between vice and virtue that was echoed by the city itself. In 1897 New Orleans’s city council voted to establish a legalized red-light district in a corner of Tremé in an attempt to regulate the rampant prostitution. The district was nicknamed Storyville after Sidney Story, the unlucky alderman who suggested the plan.

When Nat was twelve, his father ran a saloon as a side business on the edge of Storyville, where people could stop off for a drink before heading to a gambling den, brothel, or cabaret. To entertain his customers, Paul might have hired a “professor,” one of the black piano players who were flocking to Storyville at the turn of the century, where they experimented with playing a new musical form, jazz. Segregation wasn’t strongly enforced in the red-light district; men and women of all races drank and flirted side by side.

For a colored boy on the edge of puberty, the scene in Paul’s bar offered a shortcut to manhood, compared to the strategy of patience and virtue endorsed by the world at large. But this underworld was threatening too. These pleasures of booze and sex could anesthetize a young man, content him with the status quo, and condemn him to becoming the image drawn by his accusers.

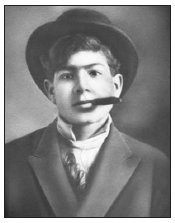

When it came time for Nat to begin courting, the consequences of his father’s behavior would make themselves known. If Nat’s marriage to my grandmother Edna Miller in 1917 was any indication, he was forced to look outside his family’s social circle. While the Millers were also Creoles of color, they didn’t belong to any of the community’s elite benevolent societies. Edna’s father was a laborer, and her mother hired herself out as a cook. By age thirteen Edna had quit school and gone to work rolling cigars in a factory and sewing for a local tailor to help make ends meet—another sign that her family wasn’t as refined as her future husband’s.

There were also whispers that Edna’s grandmother had been a prostitute, and that her mother was the offspring of a white Confederate general. Whether or not the rumors were true, the fact that Edna’s grandmother had consorted with at least four different men, not all of whom she married, would have raised eyebrows. After a childhood like hers, Edna may have been inclined to look past Belhomme’s proclivities. Also, Nat had begun to get his own construction jobs: in their first three months of marriage, he landed contracts totaling almost $9,000 ($130,000 today). Edna must have been relieved to let someone else support the family for a change.

When my father was born, on July 16, 1920, Nat and Edna were living in half of a shotgun house on St. Ann Street in Tremé. Edna’s mother lived there too, which made life in the three small rooms rather cramped for the young family. My father’s sister Lorraine was two years older, and Shirley arrived three years after my dad. My father’s few recollections of New Orleans paint an atmosphere that was congenial and cozy. In the evenings the neighbors sat out front of their houses and chatted with the passersby. Weekends were spent visiting with family. The days ran into one another, all hot and humid, wrapping my father’s childhood in a tropical sultry innocence.

But there were tensions in the Broyard household too. While both Nat and Edna were playful and loving with their children, their differences in temperament grated on their affection for each other. Nat told wonderful stories, embellished with improbable details, while Edna clung literal-mindedly to facts. He wasn’t much of a conversationalist and she was sociable, making friends easily. He walked quickly—a man with a purpose—yet with style, arching his back and kicking out his heels. She moved slowly, “like a glacier,” because her feet were bad and she was always in pain. My grandfather shared a bit of his father’s fondness for excesses—he smoked a long pipe, wore his cap pulled down over one eye, pulled his pants up toward his chest to show off his long legs. Edna summed up life with the precision of an accountant and had a talent for advising people how to solve their problems.

The real conflict, however, lay between Edna and the Broyard family. She was unused to such a patriarchal culture. Her childhood had been mostly dominated by women: her mother, aunt, and grandmother. As a Broyard wife, she was expected to wait on her husband, make all of his clothes (even his underwear), and defer to the men of the family. After working and earning her own money for so long, she didn’t take easily to this subservient role.

And her father-in-law was such a domineering presence in their lives. Every Sunday the family was expected at Belhomme’s house for supper. Because Nat depended on his father for his paycheck, the family didn’t have control over their own purse strings. It was Paul who headed to the registrar to record the birth of my father in 1920. After his wife’s death, in the summer of 1921, Belhomme became even more overbearing.

Rosa had always managed the household, watched the finances, and ensured that her husband’s peccadilloes didn’t interfere with the family dinner. But her death left Belhomme without a leash at the very moment that the city’s racial wardens were cracking down. Over the next ten years, he veered toward ruin.

The story in the family went that after becoming a widower, Paul began spending the down payments from his construction contracts on “fast women and slow horses.” When he needed to buy materials for the jobs, he’d seize his sons’ savings to replace the squandered sums. Nat couldn’t stop his father because he had granted Paul power of attorney, but he probably would have given him the money anyway. Since Paul was sixteen, he’d taken care of everyone: his mother and five brothers, then his wife and seven children. Paul had provided jobs for his sons and looked after all of his kids’ families. He’d earned a little paying back. And he was the measure by which the fortunes of the rest of them rose and fell, so it was in their best interests to protect him.

Nat would have been motivated to help his father by love and sorrow too. He must have seen how Paul’s life had become circumscribed by loss—of his wife, his Creole culture, and his place in the world. And so Nat indulged his father’s gambling and women—pastimes that could make Paul feel like a man again, at least for a night. But Belhomme’s indulgences began to hinder Nat from being a man himself. Besides his three kids with Edna, he had to support another daughter, Ethel, from his first wife, who’d died back in 1915. And so when Edna began to nag her husband to move up north, where there was plenty of construction work and Nat would be able to hold on to his own earnings, he let himself be talked into the idea.

Since World War I blacks had been fleeing the South in huge numbers in search of better economic opportunities and a break from Jim Crow segregation. During the Great Migration, as the movement was called, roughly 1.5 million African Americans moved to urban centers such as New York, Chicago, and Detroit. For Edna the decision to join them, like so many things in her life, was practical. Anyway, she didn’t have the same attachment to New Orleans or its Creole culture that her husband did. She wasn’t raised speaking French. Her people hadn’t been active in the Republican radical movement. Her sense of self-worth didn’t depend on the fading Creole legacy.

Nat was thirty-eight when he finally agreed to leave New Orleans. By this time, he might have realized that he had no choice at all—the world of his childhood was heading toward extinction. While he kept to his promise to never go back—although my grandmother and my aunts made a few trips down south during his lifetime—Nat remained nostalgic for the city he’d loved. He also was faithful to its Creole legacy, including the disdain for blacks, feelings of betrayal by the Catholic Church, and notions of manhood that had characterized the community in its waning years.

If Nat also held his father and his extravagances responsible for the decision to move north, he kept these criticisms to himself. My father grew up hearing only romantic stories about the “operatic character” Belhomme. But neither, apparently, did Nat blame Jim Crow for his father’s decline in society. To acknowledge the effect of the color line on his family would mean acquiescing to its black-and-white depiction of the world, and Nat held fast, even up north, to the Creole’s intermediary position in the racial order.

It was winter, early in 1927, when my father boarded the train for New York City with the rest of his family. He was six and a half years old. Any excitement he felt about the prospect of an overnight train ride to a fabled northern city may have disappeared on entering the Jim Crow car that his sister Shirley recalls taking. These coaches were typically positioned directly behind the locomotive, and the air stank of smoke from the engine’s exhaust. Baggage belonging to white passengers often occupied the seats, leaving little room for the colored riders. Bathrooms rarely worked, and the coaches were infrequently cleaned. Since blacks were excluded from dining services, families had to bring enough food for the forty-hour journey, adding to the smell and garbage. It’s not unlikely that this train ride was my father’s first foray into a “colored” facility.

The world of my father’s childhood in New Orleans had consisted of his house, his grandparents’ house, his block, church, and school, and occasional trips to the Creole market in Tremé. He spent most of his time with people like himself: family members and other Creole kids from his neighborhood. If he’d been shielded from the contingencies that the South forced upon colored people, the trip north would have made them clear, especially after crossing the Mason-Dixon Line and arriving in Washington, DC. There Jim Crow service ended, and the family was able to move to the more pleasant cars and sit in the company of white people.

The journey from South to North was my father’s first trip from black to white. He saw that crossing the color line could be as simple as walking a few steps down the platform of Washington’s Union Station and as devastating as his father’s mood on arriving in New York City. Looking back on this moment, my father later wrote, “[My father] had left the French Quarter a popular man, but he got off the train in Pennsylvania Station to find snow falling and no one there waiting for him.” Ten years later my father would himself eventually have to choose between the world of his family and childhood and a new world where he could create his own history, with all the contradictions that implied.