My father’s family settled in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, which in 1927 was known as Stuyvesant Heights. It was middle-class, 90 percent white, and “one of the most attractive home sections in the entire boro,” according to the Brooklyn Eagle. By the time I moved to Brooklyn, in 1996, Bed-Stuy had long been recognized as one of the country’s worst urban ghettos. Its name—synonymous with poverty, gang violence, teenage mothers, and crack—served as shorthand for the hard lot of African Americans. Most whites, along with many blacks, wouldn’t dare to go there.

When someone asked my father where he was from, he answered simply “Brooklyn” or offered nearby Brownsville (a neighborhood that, ironically, has since developed a similar reputation to Bed-Stuy). He may have justified his evasion by reasoning that the integrated middle-class environs of his childhood weren’t the same place as the notorious Bed-Stuy. But he was also trying to distance himself from the events that had brought about Bed-Stuy’s transformation—events that conflated blackness with desperation in white America’s imagination, that circumscribed the dreams and opportunities for a bright colored boy growing up on those streets, that made the desolation of Bed-Stuy inevitable. To my father’s mind, leaving behind this hard lot necessarily meant leaving behind his hometown and the people he’d known there too.

Blacks have lived in Brooklyn since the midseventeenth century, first as slaves, then as free people of color after slavery was phased out in New York State in 1827. By the time my father’s family moved to Brooklyn, the borough had developed a reputation as home to a better class of colored people, but it didn’t offer much of a black community. By far in the minority, blacks were scattered across a half-dozen different neighborhoods. In the early years of the Great Migration, most southern Negroes who came to New York City were heading to Harlem, considered the “Negro Capital of the World.”

During the 1920s alone, nearly 100,000 blacks streamed into Harlem, more than doubling its population. The influx of so many newcomers—who arrived with few resources and no jobs—quickly led to overcrowded slums, which helps to explain why my grandfather chose Brooklyn instead. Also, after growing up Creole, living in the center of American black life wouldn’t hold much appeal for Nat. Stuyvesant Heights, on the other hand, had enough black people that his younger daughter, Shirley, who was turning out to be browner than the rest of them, wouldn’t cause anyone to look twice, and plenty of whites among whom the family could get lost if they ever needed to.

My grandfather found construction work right away. For $50 a month, he rented the family an apartment on the top floor of an apartment building on a busy avenue. At age six my father became a city boy. The double-laned roads filled with cars and lined with tall brick and stone buildings were nothing like the narrow streets and one-story wooden cottages of Tremé. In New Orleans my father had run around outside in his bare feet, eaten fresh figs from a tree in the backyard, sat under the overhang of the shed’s tin roof listening to the thrum of rain during storms. In Brooklyn he and his friends played stickball in the street, and he had to ride his bike to Prospect Park if he wanted to walk around without his shoes on. Anyway, it was usually too cold.

The people in the neighborhood were different too. Russian, Jewish, Irish, and Italian immigrants lived among a handful of southern Negroes and transplants from the West Indies. My father’s parents knew only one other Creole family, and they lived way out in Queens. My father later recollected: “In the 1920s in New York City everyone was ethnic.... We found our differences hilarious. It was part of the adventure of the street and the schoolyard that everyone else had grown up among mysteries.”

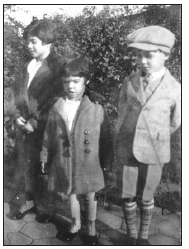

My father’s two best friends during childhood were both “colored,” meaning that their families were mixed-race and tended more toward a middle-class lifestyle than “blacks.” The family of one of the boys, Carlos deLeon, became friendly with the Broyards and often shared Sunday meals with them. My father and the other boy liked to gang up on Carlos. My father would ask him how to spell a word, and Carlos would answer correctly, but my dad and his sidekick would insist that Carlos had gotten it wrong, enraging him in the process.

Carlos was darker than my father, which introduced a subtle subtext into their play. As small as the Negro population in Stuyvesant Heights was, it contained a rigid hierarchy, with the light-skinned descendants of free blacks or Caribbean emigrants on one end and the darker sons and daughters of former slaves on the other. The fathers in the uppermost class were all professionals—dentists, doctors, or lawyers. Their wives didn’t work, except as volunteers at the National Association of Colored Women or the Brooklyn Urban League. These families owned their own houses and drove their own automobiles. During the summer they vacationed at one of the black resorts: Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard or Sag Harbor in Long Island.

While this class thought of themselves foremost as Negroes—striving for the betterment of all their people—they didn’t mingle with the more disadvantaged among their race. The singer and actress Lena Horne, who has been described as America’s first black movie star, came from the colored bourgeoisie of Stuyvesant Heights. In her book about her family’s history, Horne’s daughter, Gail Lumet Buckley, described her maternal grandparents as representing “the upper class of America’s ‘untouchable’ caste—the small brown group within the large black mass.”

No matter how light their skin or esteemed their profession might be, however, the white world still didn’t want any Negroes living or working near them. As Buckley points out: “Although members of the black bourgeoisie were vastly more successful than their poorer and blacker brethren, they rarely had opportunities to make real money....Who you were and where you came from—‘roots’—meant more than money.”

In New Orleans the Broyards, by virtue of who their people were, had belonged to the better set of black people. But in Brooklyn they didn’t quite measure up. Their pale skin was all right, but neither Nat nor Edna had more than an elementary school education. Also, while the white side of the Broyard family tree had been in Louisiana since the colonial era and the African side had arrived from St. Domingue as free people, there weren’t any other Creoles around to attest to the illustriousness of their connections.

The Broyards had been in Brooklyn for two years when Nat received word that his father’s house in New Orleans had been seized by the sheriff for failure to pay back taxes. Fourteen years before, Paul had put the property in Nat’s name to protect his investment should his construction business ever run into trouble. Paul’s “slow horses and fast women” had finally caught up with him, and he needed to sell the house to pay his debtors. One May morning in 1929, Nat headed to a notary in downtown Brooklyn to get power of attorney authorizing his father to unload the property.

Nat must have been grateful that he didn’t have to witness his father’s final fall from glory, but the sale of the house was also a loss for him. His dad had owned it since before Nat was married; it was where the family had always gathered. Nat likely celebrated his wedding there and the baptisms of his children. Even if my grandfather wanted to go back to New Orleans, he no longer had a home to return to. At the same time, Nat didn’t feel at home in Brooklyn.

My father, reflecting on his childhood, noted that his father turned into a “silent and solitary figure in New York,” after being “dislocated by moving...from the intimacy and immediacy of the French Quarter to an abstract and anonymous city.” In New Orleans, Nat had six siblings and a dozen aunts and uncles. He was kin one way or another to almost everyone he knew. In Brooklyn he had no one with whom he could share all the Creole customs that had shaped his first thirty-eight years, no one with whom he could speak the French patois of his childhood. Yet there was no denying that living up north had improved his family’s chances for success in the larger world.

My father and my aunts were attending a good integrated elementary school down the street. In New Orleans black people had to send their children to one of the private colored schools to get a decent education. If they couldn’t afford the tuition, the only other option was passing for white. In a few years, one of Nat’s cousins would change his last name—to avoid being associated with any black Broyards—in order to enroll his kids in a white school. His wife had never learned how to read in the city’s black schools and she was determined to secure a better future for her children.

In Stuyvesant Heights, a person could go where he wanted without having to confront signs for coloreds and whites. While prejudice and de facto discrimination certainly existed—blacks of all shades were routinely refused service in local restaurants—white supremacy wasn’t always presumed to be the natural order. When the ushers at the Bedford movie theater tried to Jim Crow some patrons, charges of discrimination were reported in the Brooklyn paper. A local Episcopal minister who sent letters to his black congregants discouraging their attendance was met with a national outcry. White clergies from around the city publicly censured him while opening their own doors to his colored worshippers. Despite these improvements over the racial attitudes in New Orleans, a mood of loss and longing lingered beneath the cozy surface of the Broyards’ family life.

At night my father and his sisters would do their homework around the dining room table, while Nat sat in his armchair, smoking his pipe and reading the paper. Nearby in the kitchen, Edna prepared dinner. Sometimes she brought out a bowl of peas for the girls to shell or a pot of potatoes for her husband to mash. In minutes Nat had the potatoes whipped into a high fluff, his arm moving up and down as fast as a piston. After dinner they listened to radio dramas, The Shadow or The Lone Ranger, or they played a few hands of fan-tan. Sometimes my dad made them laugh by putting on a record of the Cuban music that he loved and trying to imitate the dances.

Edna doted on her son, worrying that he was too skinny, and regularly chased him around the dining table, trying to force Scott’s Emulsion or cod liver oil down his throat. During the summer months, she bribed him with Tarzan books to stay inside during the hottest part of the day, and his lifelong love of reading was born. Lying on his bed inside the dark apartment, the curtains drawn against the sunlight, my father could escape his father’s silences as he swung from vine to vine through the jungle.

Eventually my father graduated to reading Alexandre Dumas, whose complete works, including The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers, lined one shelf of the family’s dining room. Dumas’ father was the son of a Frenchman and slave woman in St. Domingue, a legacy that gave the writer a common history with Creoles. For my dad and his sisters, Dumas’ books, their mother’s unique recipes, and the strange French their parents spoke when they didn’t want the kids to understand them were everyday reminders of their Creole identity. Yet neither my father nor my aunts were exactly sure what Creole was. Shirley only understood that it was a different kind of African American.

My father and his sisters weren’t taught to speak the language themselves, nor did they grow up hearing about the history of Creole activism and their own family’s contribution. From Nat’s perspective his father’s political career was a series of defeats. Nat was seven when the Plessy challenge was lost, nine when blacks were disenfranchised by the new state constitution, eleven when his dad was ousted from the Republican Party, and thirteen when Paul stopped voting in elections. Rather than recount these failures, Nat regaled my dad with tales of the impressive buildings his father built, his conquests of the ladies, and the stylish and charismatic figure he cut as Belhomme, the beautiful man.

Perhaps it was these stories—or Nat’s animation in telling them—that sparked my father’s interest in his roots. As a teenager he decided that he wanted to learn how to speak Creole too. Maybe he could follow these foreign words to his father, the same way that he’d followed Tarzan on those jungle vines. But the Brooklyn public schools didn’t offer Creole instruction, and my father’s parents weren’t inclined to teach him themselves. What was the point of their son learning this vestigial language? Even with all its immigrants, New York was an American city that offered a chance at the American dream. Better that my father focus on his studies, so he could do well on the civil service exam and get a good job at the post office, with a steady income and a pension. Even if their place in society had fallen since leaving New Orleans, and even though Nat’s removal from the Creole culture had left him heavyhearted, Nat and Edna could console themselves that New York offered the chance to make a better life for themselves and their children. But then came the Depression.

The stock market collapse in 1929 made things difficult for everyone in New York, but as the “last hired and first fired,” blacks were particularly vulnerable. There was no recourse for job discrimination during the worst years of the Depression—President Franklin Roosevelt didn’t establish the Fair Employment Practices Commission until 1941—and newspaper want ads regularly specified “whites only” among their hiring specifications. Even jobs as maids or laborers, once considered the exclusive domain of African Americans, started going to European immigrants. When blacks did get work, they were routinely paid less than whites. Trade unions traditionally blocked the entrance of African Americans; in 1930 only one in twenty black workers belonged to a union, compared to one in five whites.

My grandfather had joined the carpenters’ union when he first arrived in New York by passing as white. Membership qualified him to work on bigger commercial buildings, and his experience earned him a foreman’s grade, just one step below the superintendent. It was his job to translate the architect’s plans into orders for his crew of carpenters to carry out. Between this responsibility and his respectable paycheck, my grandfather was very proud of his job. On the work site Nat kept a hammer in the belt of his overalls, and regularly whipped it out to demonstrate how something was done. My father often bragged how his father could drive home a two-inch nail with two strokes of his arm. Nat had built an elaborate wooden toolbox outfitted with slots and compartments to carry his tools back and forth to the job site. In the neighborhood he could often be seen walking down the sidewalk with the long toolbox balanced on one shoulder, his other hand on his hat, ready to tip it for the ladies.

But even passing as white couldn’t protect Nat during the Depression. He was out of work for much of the 1930s, losing his dignity as much as his income. Over an eight-year period, the family moved five times in search of ever cheaper apartments. In one place, Edna tended the building’s furnace to offset the rent. The next apartment was a railroad flat adjacent to the El—Lexington Avenue’s elevated trolley. For three years my father’s sisters slept in a room whose window was eye level with the train tracks. Finally, in 1934, my grandmother took a job ironing six days a week at a commercial laundry. The owners hired Edna because they thought she was white.

Even before the Depression, utility companies, department stores, factories, hospitals, hotels, and New York City’s transit companies had all practiced racial discrimination in hiring. For the paler Negroes of Stuyvesant Heights, passing for work was commonplace and acceptable. Everyone knew that most of the salesgirls and elevator operators at the Abraham & Strauss department store in downtown Brooklyn were really light-skinned blacks. Other colored people often applauded these racial infiltrators, happy to see one of their own “getting over.” Some of the darker blacks even encouraged the practice, since it meant less competition for the few jobs available to their race.

In New Orleans the phenomenon had been even more widespread. The ubiquity, however, didn’t make passing any easier. In the early 1970s, the historian Arthé Agnes Anthony collected oral histories about the practice from septuagenarian and octogenarian New Orleans Creoles. As a man who passed in order to work at a printing company explained, “The whites would be talking about Negroes and you’d have to take it. Once I had been seen at night...and I was later asked what was I doing with all those niggers. I told them that it was none of their damn business who I was with. They never asked me that anymore, but I didn’t like it.” This fear of detection and the stress of distancing oneself from one’s coworkers—you couldn’t socialize with them or ever invite them to your house—compelled many Creoles to return to colored employment, no matter the loss of wages.

But as the Depression worsened, colored employment in New York City wasn’t an option for my grandparents. Nat worked mostly in Manhattan, where he ran less risk of bumping into someone who knew about his background. For Edna, whose job was only a half mile from the family’s home, the threat of discovery was greater. Other blacks tended to protect people who were passing—by not acknowledging the person when in public—but a white neighbor wouldn’t be as inclined to keep a black person’s secret.

My grandmother was well known around Stuyvesant Heights. She often stood by the front gate of the yard, chatting with passersby. She had a talent for drawing people out about the difficulties in their lives and would freely offer advice about what someone should do in any given situation. She also had a habit of unconsciously mimicking a person’s accent. Before long she’d fall into an Irish brogue, Caribbean lilt, or the Yiddish inflections of a neighbor, which made her daughter Shirley worry that people might think her mother was mocking them.

While visiting my aunt Shirley, I try to ask, gingerly, what it was like for her to grow up under these circumstances. The subject is uncomfortable for the very fact that Shirley, unlike the rest of her family, couldn’t pass for white. In New Orleans I heard stories about Creole families who rejected their own children because they were too dark. Sometimes these families justified their decision by the fact that the child made it impossible for them to live as white at a time when passing was one of the few means of survival. Other times a family had simply absorbed the prevailing attitudes about skin color to such a degree that they willingly betrayed their own flesh and blood.

Shirley acknowledges that her childhood was probably very different from her brother’s and sister’s. On the street or in school, people knew what Shirley was by looking at her, which made her prey to the kinds of subtle prejudice—a waiter ignoring her at the lunch counter, a white classmate rebuffing her overtures of friendship—that black people experienced all the time. My father and Lorraine, on the other hand, could go through their day unharmed by such offhand cruelties. But I wondered if these differences in experience extended to their home life too.

We sit at Shirley’s kitchen table, where we always sit during our visits. Post-its decorate the cabinet doors, with reminders about upcoming appointments, calls to be returned, bills to be paid. In her early eighties, my aunt still goes out most nights, to meetings of her book club or performances at Lincoln Center or the Brooklyn Academy of Music—but I recognize these reminders as the efforts of a proud woman to resist the tide of aging. My aunt isn’t the type to talk easily about her vulnerabilities.

“Do you think that your mother or father ever had any close calls at work?” I ask. “It must have been sort of stressful for them. And for you.”

Shirley dismisses the question with a shake of her head. She says that she doesn’t know for sure, but she doubts that her parents ever worried about being found out. “I never worried about it myself,” she adds.

“But you knew, for example, that you couldn’t visit your mother at her job.”

“I had no desire to go to the Laundromat. It didn’t interest me.”

Shirley explains that after school she and Lorraine would do the grocery shopping and start dinner, and when their mother came home, she would finish the cooking. Their home life was just like other families’.

I tell Shirley that my father described the experience a little differently to a friend. He said that one day his father had sat the family down in the living room and announced that they were no longer going to be black. Because Nat and Edna had to pass as white for work, the kids had to be white now too. “Imagine having someone say that to you!” my father had exclaimed to his friend.

“Well, if it happened, I wasn’t there,” Shirley says flatly. I can see why she might doubt this account. How, after all, could her father have acted as if race was elective, when for his youngest child it obviously wasn’t?

Shirley tells me that she was never treated any differently in her family. “The only thing I can remember,” she says, pausing, “is them teasing me about being the cookie they left in the oven too long.”

I can’t help laughing. “They said that?”

Shirley laughs too, in amazement. “Yes, I was the brown sugar cookie or the ginger snap.”

“That must have hurt a little.”

Her face clouds. “Well, I still remember it, so I guess it made an impression.”

It’s clear from talking with Shirley that there wasn’t much conversation in her family about racial identity. It seems possible that my father and his sister could have grown up under the same roof with vastly different understandings about what race they were supposed to be. Neither my father nor his sisters were advised, for example, about how they should present themselves when applying for a job or meeting new classmates. Shirley doesn’t know how my dad and Lorraine were perceived in high school. “We never discussed it,” she says.

The example set by their parents had to be confusing. While the family visited with black people, attended black social events, and remained in the neighborhood even as white people moved out, Nat and Edna avoided being labeled as “black” themselves. Shirley remembers how the family sat apart from the other black families at the beach in Coney Island. In 1930, when the census taker came around, Edna claimed that her mother was born in Portugal, and Nat reported that his parents came from Mexico. Despite these attempts to explain away their dark hair and tawny complexions, the census taker recorded the family’s race as black anyway. When I ask Shirley about the deception, she shrugs and says, “Still trying to keep up the fiction.”

Around the time of the 1930 census, Nat’s brother James and his nephew Jimmy Jr. arrived in Brooklyn from New Orleans. Jimmy Jr. moved in with my father’s family until he found a place of his own. When I track him down in Louisiana, Jimmy, who is eighty by this time, tells me that my grandfather was never colored in New York. Jimmy knows that this was true, because Nat and Edna had told him so. Yet he also recalls black people visiting the Broyard house, which seems unlikely if the family was trying to pass among its neighbors.

Kathy Jeffers, who was my aunt Lorraine’s best friend during the latter part of the 1930s and was herself recognizably black, also has the impression that Nat was passing both for work and around home. One day in the early 1940s, she saw Mr. Broyard in the street and said hello, but he kept walking without acknowledging her. She confessed the incident to Edna and Lorraine, and she recalls being told that Nat was trying to protect his employment. But again this explanation didn’t quite make sense, since Shirley, and later her brown-skinned husband, was living in the Broyard household.

When it came to race, however, Nat wasn’t known for being logical. Shirley describes her father as “the biggest racist you ever set your eyes on,” adding that he hated everyone: blacks, Catholics, and Jews alike. Every night my grandfather read William Randolph Hearst’s newspaper, the notoriously conservative Evening Journal. She remembers her father agreeing with everything the paper said and even saving the front page each day for posterity. When the editors of the Brooklyn Eagle suggested that the influx of blacks into Stuyvesant Heights was bringing down the neighborhood, Nat agreed with them too. His disdain for African Americans underscored his feeling of separateness from them—a line of distinction that only deepened as the complexion of his neighbors darkened.

With the onset of the Depression, residents of Harlem began relocating to Brooklyn to escape the worsening ghetto conditions. But those same problems followed them across the East River. The deteriorating economic climate forced black homeowners in Stuyvesant Heights to take out second mortgages and then take in renters to pay for them. In 1931 the Brooklyn Eagle first described the central Brooklyn neighborhood as Bedford-Stuyvesant, linking together Stuyvesant Heights and adjacent Bedford Corner. Over the next ten years, the moniker gained currency—usually with negative connotations—as the boundaries of Bedford-Stuyvesant were increasingly defined by the presence of black people.

Ironically, federal policies implemented by Roosevelt’s New Deal hastened the neighborhood’s downfall. In 1933 the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was established to stem home foreclosures and bank failures. The agency developed lending guidelines to help ensure that struggling financial institutions would get back on their feet. To that end grades of A, B, C, or D were assigned to a neighborhood based on condition of its housing stock, transportation and utility services, maintenance of homes, and “quality” of the population. Specifically, federal agents looked at the percentage of blacks and foreign-born residents in a community and whether either population was on the rise. Needless to say, Bedford-Stuyvesant earned the worst grade, D.

The historian Craig Steven Wilder, in analyzing the HOLC’s “Residential Security MAP” for Brooklyn in his book A Covenant with Color, found that while a heavy concentration of Jews, Irish, or Italians risked bringing a neighborhood a negative rating, the presence of African Americans absolutely guaranteed it. “Bensonhurst and a portion of Flatbush, with sizable Italian populations, managed at least B2 grades, just as a number of Jewish areas received B or better ratings. In contrast, not one of the eighteen neighborhoods that received a B2 or better had any black residents, except for Crown Heights, where the black population was described as ‘Nil,’ meaning ‘2 or 3 families.’”

Neighborhoods with D ratings appeared in red on HOLC’s map, which led to the infamous term “redlining.” By deeming these areas bad investments, the federal government helped to make them so. The difficulty in obtaining loans to buy homes or maintain existing properties in Bedford-Stuyvesant further decreased property values. Trying to cut their losses, whites sold their homes, often to unscrupulous white investors, who would then break up the houses into apartments, which they would rent out at inflated prices to blacks who found themselves unwelcome elsewhere.

As the black community in Bed-Stuy grew, class conflicts sparked between the old “colored” group and the new “black” population, with the flash point often occurring among the teenagers. The lower-class kids knew, if perhaps implicitly, that my father’s family, for example, fared better than their own because his parents could pass as white. Despite rough times there was never any shortage of food or serious deprivation for the Broyards. Edna continued to make her apple pies and yellow cakes throughout the worst years of the Depression. One December, when my grandfather hadn’t worked for a while, it looked as if the family would have to forgo Christmas. But at the last minute, Nat landed a job and surprised them by coming home with a tree and a bag full of presents.

During high school my father and his friends had the leisure time and pocket change for a jam-packed social life. In the summer they played tennis at the courts down on Fulton Street. In the winter they skated at the rink on Atlantic Avenue. On the weekends they took their dates to the movies at Lowe’s theater and then to Bruggerman’s for ice cream afterward. On any given night they could be found at one of the girls’ houses listening to records—Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Coleman Hawkins—and polishing their moves for an upcoming dance.

Most dances were sponsored by private clubs and were invitation only. The Guardsmen, a social club started by the black bourgeoisie in Brooklyn, held three parties annually, often at the Savoy Theater in Harlem, at which the Duke Ellington band regularly played. The biggest event of the year was the formal Christmas dance thrown by the Comus Club, usually held at the St. George Hotel in Brooklyn Heights. Young men and women from the best black families in Washington, Philadelphia, and Boston flocked into town to attend the annual party.

Meanwhile, by 1938 the Brooklyn Urban League was reporting that 90 percent of black Brooklynites depended on some kind of relief. Many children had to drop out of high school to look for full-time jobs. Their families were crammed into one-bedroom apartments, and they had no hopes of attending college. Needless to say, they weren’t invited to the Comus Christmas dance.

“Other blacks were jealous of us. We got into a lot of fights,” remembers Robbie King, one of my father’s friends. These other kids called Robbie and my father’s circle the four hundred, after Lady Astor’s four hundred—the members of New York society deemed worthy of an invitation to her annual ball. Marjorie Costa, a childhood friend of my aunts, tells me how in high school a gang of darker-skinned, poorer kids targeted their crowd. “Your aunt Lorraine was beaten by one of the gangs,” she explains. “They were going alphabetically.” With her turn coming, Marjorie got a rival gang to fight for her, but she understood the roots of the tension. “Many of our group were snobs and didn’t want to talk with [other kids] if they weren’t the right color and didn’t dress the right way.” The hard-off boys particularly resented that the girls in my dad’s clique wouldn’t go out with them. At the same time, lighter-skinned boys, including my father, were fooling around with the girls in their crowd. “They only wanted them for sex,” Marjorie says, disapprovingly. “They wouldn’t take them to a movie or to Bruggerman’s ice cream parlor.”

My dad once told a friend in whom he had confided about his racial background that he’d become such a fast runner from being chased by black kids during his childhood. Sometimes these kids caught up with him and he’d come home with his jacket torn, but his parents never asked what happened. Perhaps Nat didn’t want to acknowledge that his passing for white and superior attitude toward blacks had contributed to his son’s problems. Or he simply viewed these street scuffles as a boy’s rite of passage. Nat had probably gotten into fights with the American blacks in New Orleans when he was a kid. But for my dad, his father’s feigned ignorance was so painful that recalling it to my mother fifty years later made him break down into tears. It was the second and last time my mother ever saw my father cry. (The first was during his best friend’s funeral.) During childhood, though, it was easier for my father to turn his hurt into anger, which he eventually redirected toward black people.

Learning about my father’s experiences growing up made sense of a story that my father liked to tell from my own childhood. When my brother was eleven or so, my dad took him to the movies in Oak Bluffs, a town in Martha’s Vineyard with a large number of African American vacationers. After the film my father had to use the bathroom and sent Todd outside to wait for him. When my dad exited the theater, he found my brother in a doorway down the street, having a fistfight with a black kid a head and half taller and three or four years older. My father, who had taught my brother how to box, would jab and feint at this point in the story, demonstrating how his son had knocked down this kid twice his size.

The detail that always struck me was not Todd’s prowess at boxing but my father’s disconcerting glee that my brother had trounced a “tough black kid.” Todd couldn’t remember anymore what started the fight, but he did recall that our father had stood back and watched him rather than breaking it up. People say that having children gives you the chance to relive your own childhood. With his victory Todd had unwittingly settled an old score for our father.

In a similar vein, Todd was taken out every month or so for “father and son nights,” while I had no special dates with our dad. Since my brother, particularly as a teenager, was himself a fairly silent character, my father claimed that if he didn’t hold Todd captive at a dinner table once in a while, he would never learn anything about him at all. My father was hoping that he and my brother could learn to talk as friends the way he and his father never did.

My grandfather had trouble simply looking my father in the eye. In his spare time, Nat liked to make furniture in a workshop that he’d set up in the basement of their building. As a young child, my father followed his father downstairs and tried to place himself in the way so that his father was forced to meet his gaze. Sometimes Nat would talk to himself as he worked, and my dad would strain to listen, in case his father mentioned his name.

As an adult my father blamed New York for turning his father into this taciturn, evasive man. In New Orleans his father had been “a popular figure, a noted raconteur, a former beau, a crack shot, a dancer, a bit of a boxer.” He was the kind of man who would suddenly throw himself upside down and walk on his hands over to a friend’s house for a laugh. But after moving north, Nat became preoccupied, always listening for something, “some New Orleans jazz, or a voice telling him a story.” My dad decided that his father “lived in New York under protest, a protest that he never admitted even to himself. He was ashamed to think that he had been pressured into leaving the city he loved.”

What my father didn’t acknowledge was that in Brooklyn, Nat was just another light-skinned black guy who could only make it in the larger world by presenting himself as something that he wasn’t. My grandfather was reacting not only to New York but also to the question the city forced on him: Was he black or was he white? Yet for my father to see the box that race had forced Nat into, he would have had to recognize that he was similarly hemmed in.

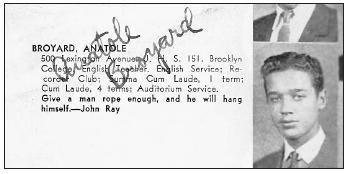

My father attended Boys High, located in Stuyvesant Heights, not far from where the Broyards’ apartment overlooked the El. Although no tests were required for entrance, the high school had a reputation for being where the smart kids went. The students, who came from across Brooklyn, were mostly the sons of Jewish emigrants from Poland, Russia, and Germany. A handful of my father’s friends from the neighborhood also attended Boys High. In the 1930s there wasn’t much racial tension, and the black and white students mingled easily with each other. A white classmate, Harold Chenven, assumed that my father was white too until their junior year, when my dad leaned over during a break in Ms. Wilson’s literature class and whispered that he was a Creole from New Orleans.

Recalling this conversation sixty years later, Harold says, “I guess I was worldly enough then to know that he was telling me he was of mixed racial parentage.” In hindsight Harold surmises that my father wanted to pass for white and that his confession “was like trying it on for size.” Harold didn’t answer, but he thought to himself that Bud Broyard didn’t look like a Negro. His skin was as pale or even paler than his own.

Not everyone was as worldly as Harold when it came to understanding that Creole suggested mixed race. By describing himself that way, my father could avoid the black/white question and let people draw their own conclusions. But this was more than a tactic of obfuscation. Just as this heritage could momentarily lift the fog of distraction and defeat surrounding his father, it also offered a way for my dad to explain himself to himself. In the absence of any real knowledge about his legacy, my dad turned New Orleans into a mythical city filled with irreverent characters: the swashbuckling pirate Jean Lafitte, romantic adventurers lifted from the pages of an Alexandre Dumas novel, and his own lady-killing grandfather. At college my father discovered how his New Orleans roots could even put an exotic spin on his difference from everyone else.