When my father entered Brooklyn College in January 1937, the first thing that people noticed about him was how out of place he seemed. He was only sixteen, having skipped two grades during elementary school, and one of the very few students who wasn’t Jewish. His classmates had never met someone named Anatole before; they’d never known anyone who was Creole or from New Orleans. He was also completely apolitical, while the rest of the students were swept up in the radicalism of the 1930s—reading the Daily Worker, holding antiwar rallies, and debating the relative merits of various socialist ideologies. My father later explained that he regarded politics as an “uninteresting argument with the real.” I imagine also that he couldn’t very well stake out a position on these social issues without first claiming his position in society, which was something he was unwilling to do.

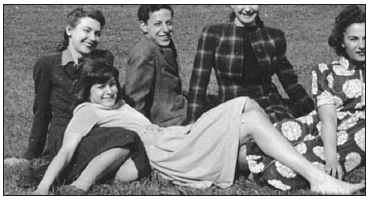

My father dressed differently from everyone else. Back then men put on dark suits and somber ties for school, and women wore knee-length skirts and plain sweaters. On top of the custom-tailored three-piece suit my father had bought with his earnings from delivering newspapers, he added a porkpie hat and short gray overcoat with hidden buttons that looked like the kind of cape someone might have worn to a nineteenth-century duel. A classmate later observed: “Anatole was the mysterious subject of many conversations, with everyone speculating about where he belonged.”

The question weighed on my father too. After his first semester, Brooklyn College relocated from its rented office buildings in downtown Brooklyn to a new forty-acre campus on Flatbush Avenue, complete with colonial redbrick buildings and the beginnings of ivy trailing up their fronts. There the cafeteria became the meeting place and testing ground for the student body. It was, in the words of my father’s future best friend Milton Klonsky, “a crowded, bustling, feud-ridden, volatile, and at times cacophonous place that had a continuous life of its own apart from that of the college itself.” A person was identified according to where he sat: there was a table for the Trotskyites, the Stalinists, the Socialists, the Communists, the jocks, the Orthodox Jews, the Catholic girls of the Newman Club, the handful of Wasps, and the even smaller handful of black students.

When Vincent Livelli first spotted my dad, he was standing alone in the cafeteria, looking for a seat among the crowded tables. “Nobody seemed to want his company,” Vincent recalls. “That coat was the problem. It was much too big for him—it must have been his father’s from New Orleans—but this was still the Depression, so I was willing to make allowances.”

Vincent was a bit of an oddball himself: an Italian Catholic from the largely Scandinavian neighborhood of Fort Hamilton. After being turned away by various fraternities, he ran for student council and lost, losing his interest in politics along the way. When he encountered my father, Vincent was peddling penny cigarettes in the cafeteria. Hoping to sell him a “loosie” after his meal, Vincent invited the odd fellow in the cape coat to sit down. My dad accepted reluctantly—lest he appear resigned to a future among misfits—and then ignored Vincent for the rest of his meal.

But the pair bumped into each other again riding home on the subway. Shouting over the loud clacking of the train across the ties, they discovered a mutual interest in Cuban music. From the time he was a kid, my father had listened to Xavier Cugat on the radio. Such was his love for the Latin bandleader that he was allowed to hog the family radio each week during Cugat’s program. Vincent impressed my dad by mentioning that he’d met some of the musicians who played on Cugat’s show in the nightclubs of Spanish Harlem.

Before long Vincent and my dad were stopping off on the way home at a bookstore in downtown Brooklyn that sold Afro-Cuban records. After winding up the Victrola, they crowded into a listening booth to decipher the lyrics full of puns and sexual innuendos. One of their favorites was “El Plato Roto” (the broken plate), about the girl who was made pregnant during the encounter that broke her hymen. Another man was tricked into paying for her abortion, which my father and Vincent thought was bad luck indeed.

One day Vincent came to my father’s house to loan him a record and was invited to stay for dinner. It was during this visit that Vincent realized, with a bit of a shock, that my father’s family was Negro. Over the years other friends of my dad’s would learn of his racial identity this same way. Yet this revelation didn’t induce them to start viewing Anatole as a black person. They all offer the same explanation: people didn’t think in racial terms back then, in spite of—or perhaps because of—the persistence of segregation. Anyway Anatole didn’t look or act like most black people. Vincent says that he was simply happy to have found a kindred spirit—someone more social than political and equally passionate about music, dancing, and women.

Flora Finkelstein at Brooklyn College was my father’s first real girlfriend. She was Jewish, although after growing up in a socialist commune in the Bronx, she wasn’t religious, particularly interested in politics, or conventional in the least. Another classmate, the writer Pearl Bell (who is the sister of Alfred Kazin and the wife of Daniel Bell, two leading New York intellectuals), remembers: “Flora wore her bangs down to her eyes and had a way of taking her shoes off and dancing in the grass in the spring, which nobody did in those days. She was eccentric and so was Anatole.”

Flora knew that my father was part black—he’d told her so—and it didn’t matter to her in the least. She was under the impression that it didn’t much matter to him either. The young couple could be seen walking hand in hand across the quad or hunched over a table in the cafeteria deep in conversation. They talked mostly about literature—not the dusty canonical texts, Beowulf and Swinburne, assigned for their English literature course—but the erotically charged works of D. H. Lawrence, the brutal nihilistic vision of Céline, and Kafka’s disturbed symbolic universe. Flora had a keen analytical mind, and her unusual upbringing gave her the courage of her own convictions. She listened closely to my father’s opinions, which made him phrase things more carefully in order to impress her. When he showed her the poems and bits of stories he’d begun to write, she encouraged him.

My father had known some classmates at Boys High who had interesting things to say about books, but he’d never before had someone with whom to share his love of literature—someone who could join him in deciphering the secret codes that unlocked these imagined worlds and celebrating the patient exquisite precision that it took to create them. For my father and Flora, books and each other were their first loves, their true loves, with each feeling redoubling the other.

In English class my father started to draw attention to himself. Pearl Bell remembers him as having a “wonderful capacity for hitting at the center of whatever it was that was being talked about.” The acuity of my father’s insights helped to erase the distance between him and the other students who were also “aware” about literature—which were the only people he cared about. In the cafeteria he took his seat beside the other literary men. Books became the place where my father could belong: his sole allegiance, his primary ethnic, political, and religious affiliation. They provided a refuge from all the boxes in his life, an opportunity to escape into himself, literally.

Back in Bedford-Stuyvesant my dad wanted to spread the news. He loaned Shirley his collection of Kafka stories. After dutifully reading Metamorphosis, she opined that a guy turning into cockroach was pretty weird. “But you see that it’s operating on more than one level?” my father pressed. Shirley was still in high school, reading Hawthorne and Mark Twain, and didn’t know anything about different levels. Anyway, who talked like that—and to his kid sister! No one Shirley knew.

My father couldn’t share his newfound enthusiasm with his neighborhood friends either. Many of them were bright, with some also earning spots at one of the free colleges, but they had more practical concerns on their minds, such as who would hire them when they graduated and what would their place in American society be. As they ventured farther from Bedford-Stuyvesant, my father’s friends had begun to experience discrimination for the first time—being turned away from clubs in Manhattan or refused service in a restaurant—and this had drawn them into the fight for racial equality.

An old classmate from Boys High, Alfred Duckett, had also been passionate about writing, publishing his poetry in the school’s literary magazine, but when he got older, he turned his attention to politics—joining the local chapter of the NAACP, canvassing the neighborhood for signatures to demand that businesses hire blacks and picketing those that wouldn’t. Duckett’s writing career increasingly reflected his concerns—he published his poetry in Negro anthologies and eventually became an editor at the New York Age, a black newspaper.

Being a black writer was exactly what my father feared. Given his racially indeterminate upbringing, he wasn’t exactly equipped to represent the black experience. Anyway, he wanted to write about the human condition—the existential problem of being, how to find meaning in an irrational world, and the possibilities of transformation; the subject matter of his literary heroes. My father saw himself as special—isn’t that what his classmates at Brooklyn College thought?—so why should he voluntarily consent to the indiscriminating smear of discrimination? Especially if he didn’t have to.

In the evenings and on the weekends, my dad hung out in the neighborhood with his friends as usual, but more and more, his real life seemed to be taking place somewhere else. My father’s regular partner at the weekend dances, Lois Latte, remembers him as seeming very distant. “Bud wasn’t like the other fellows, who were raucous and loud and always carrying on, except for that he really loved to dance.”

My father taught Lois steps that he had worked out to Artie Shaw’s hit version of “Begin the Beguine.” “I remember feeling so proud that your father wanted to dance with me,” she says. “He could have asked anybody he wanted.” Lois wasn’t surprised when she heard a few years later that Bud Broyard had gone to the other side. During the time they’d known each other, Lois’s mother had been supporting Lois by passing as white to waitress in a fancy hotel up in Westchester, making Lois inclined to defend my father’s decision. “There were times when you had to do what you had to do to live,” she reflects. And then she ventures a guess that the rest of their friends would have done the same thing if they could have.

Shirley suspects that her brother was passing as early as Brooklyn College. To his parents and sisters, he certainly seemed to change around that time. But then again, going to college was unlike anything that had ever occurred in their family. Neither of their parents had even made it to high school. And Lorraine, who was the oldest of the siblings, had opted for secretarial school instead, so she could start earning money and contributing to the household income.

“College could have meant that this is how you behave,” Shirley says. “You make new friends, you’re busy, you have homework, you have all these classes, and you have to make your way to Brooklyn College, which is not exactly around the corner.” You also learn things that make you discontented with the world that you’ve always known.

It’s hard to say when my father started presenting himself as white, if he ever explicitly did so. What’s more likely is that he didn’t identify himself as black, neglecting to mention that he lived in Bedford-Stuyvesant and avoiding the colored students’ table at lunchtime. But his transformation wasn’t as sudden or absolute as that of Kafka’s Gregor Samsa, who woke up one morning to find that he’d changed into a cockroach his parents couldn’t recognize or understand.

As my father became more articulate with his friends at Brooklyn College, he did grow less intelligible to his family—purposefully so with his father, using words that Nat wouldn’t know to pay him back for his years of silence. But his conflict wasn’t between black and white as much as it was between provincial and sophisticated, old world and modern, literal-minded and literary-minded. And this struggle wasn’t exactly uncommon among his college friends, as they too grew mysterious to their immigrant parents.

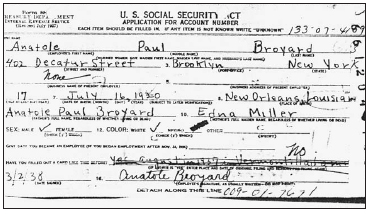

My father’s situation differed in one important aspect. Besides the universal question Who are you? that all of them were asking themselves, my father had to confront the question What are you? on occasion too. In March 1938, when he was seventeen, my father visited the local field office of the Social Security Administration to apply for a social security card. While his responses on this application concerning race represent the first tangible evidence I have of what he considered himself, the form raises more questions than it answers.

I’ve studied the muddled notations on the small sheet of paper countless times, spent hours wondering about my father’s train of thought as he completed the application. And while I don’t think that this visit to the social security office necessarily demarks a turning point in my father’s life, the occasion has become the repository for all my imaginings about the different moments over the years when he had to make a calculation about how to describe his race.

Bud retrieves an application from a stack and finds a spot at one of the counters to fill it out. In his carefully rounded schoolboy print, he answers the questions: name, address, birth date, place of birth, full names of father and mother, sex, and then question number twelve: color, with the choices white, negro, or other.

Bud has never faced a form like this before. He’s never had to answer this question. He hesitates, trying to imagine the future of this slip of paper—where it will go and who will see it; how question number twelve might affect his life. He knows very well, from his parents and people in the neighborhood, that he won’t be able to get any kind of decent job if an employer thinks that he’s black. But he also knows that no white person is going to suspect that he’s any different from themselves. He decides that identifying his COLOR on this form is merely a formality of the modern age, and whatever shadow self that is created from it will live on only in the dusty file rooms of federal warehouses. Convinced that his answer to question number twelve doesn’t matter, he touches his pencil to the piece of paper....But what should his answer be?

Bud knows what “they” think: that his color should be negro, even though the arm resting on the counter before him is no darker than the arm of the young Italian guy to his right. For that matter, his hair is no curlier than the Jewish girl’s across the room. His lips are no bigger than the lips of her father. And his nose is no wider than the broken one on the Irish thug over there. But “they” have already decided this question for him on other slips of paper stored in dusty file rooms. Bud’s birth certificate identifies him as “colored” and that’s how the census taker recorded him and his family too. If a person accepted the one-drop logic of race that seemed to be the law of this irrational land, then Bud was colored, thanks to his great-granddaddy falling for the beautiful island girl from Santo Domingo...

And what was so wrong with that? These distinctions between black and white were exactly that, arbitrary distinctions that had been imposed by “them” with no basis in fact or science. Any intelligent person knew that whatever differences existed between the races were caused by social conditions, such as poverty. Professor Otto Klineberg, student of the “father of American anthropology” Franz Boas, had just lectured at Brooklyn College on that very topic. If Bud opted against electing negro on question twelve, then he would appear to be giving credence to the “crackpot race theories” that Klineberg had just exposed.

And yet...and yet... Bud drums his fingers on the countertop. These slips of paper have a way of trailing a person around—like a piece of toilet paper stuck to your shoe. Hadn’t he heard stories his whole life in which a person’s “papers” figured as the punch line? There was the one about his uncle Jimmy, when he got into a scrape with the police down in New Orleans. They were going to lock him up in the colored part of the jail—which, needless to say, was full of roughneck lowlifes and not where his uncle belonged—until Jimmy protested that he was white and pulled out his driver’s license to prove it. The cops apologized, addressing him as “Mr. Broyard,” and let him go. Ha. Ha. Ha. His father slaps his knee. Just because Jimmy had those white papers...

Bud shifts his pencil in his grip. Anyway, he wasn’t really a Negro like “they” thought of them—the sullen toughs that were moving into his neighborhood; the poor, downtrodden, uneducated masses. His people had never been slaves; they’d never bowed and scraped before white people. What did “they” know about the wide variety of Negroes—that they ranged in color from ebony to alabaster; that some of them spoke French or Spanish in their homes; that their history had taken them across not only cotton fields but battlefields, barricades, and fields of knowledge too? And who were “they”? Where were “they”? These invisible authorities with their nonsensical rules were like something out of Kafka.

Recalling the author gives Bud a warm feeling in his chest, like the memory of a lover. Perhaps literature could provide an answer to number twelve. Bud thinks of the penultimate section of the brilliant Wallace Stevens’s poem “The Man with the Blue Guitar,” which had just been published. Yes, he would recite that to the clerk as his response to the question of his COLOR.

Throw away the lights, the definitions,

And say of what you see in the dark

That it is this or that it is that,

But do not use the rotted names.

How should you walk in that space and know

Nothing of the madness of space,

Nothing of its jocular procreations?

Throw the lights away. Nothing must stand

Between you and the shapes you take

When the crust of the shape has been destroyed.

You as you are? You are yourself.

The blue guitar surprises you.

The young Italian glances over. Bud has been mumbling under his breath. As he turns his attention back to the form, his father’s voice pops into his head: “Get your head out of your books for once, Bud. Check off white, hand in the slip, and walk away. That’s how people see you, and that’s all there is to it.”

But it’s one thing to be mistaken for white and something else to actually present himself that way. Yes, the color line is shot full of holes, and crossing it could be as easy as crossing the East River. Every day people from his neighborhood who are black when they enter Fulton Street station become white just by taking the subway to Manhattan and going to their jobs. Bud knows that people’s perception of him changes according to his context—among his colored friends from Stuyvesant Heights he’s viewed as colored; sitting with his white classmates at Brooklyn College, he’s seen as white. But he also knows that people can become exiled on the other side of the color line. He thinks of Ethel, his half sister.

When she arrived from New Orleans with her new husband, Walter, it was as if his father had woken from a long nap. Bud was ten, and Uncle Jimmy and his son, Jimmy Jr., had just come up to New York too. All of a sudden, there was a burgeoning Broyard clan in Stuyvesant Heights, and their house was its center. One Sunday his dad made a big show of having to fetch from the basement the extra leaf he’d made for the dining room table, but everyone could see how delighted he was to have so much family around.

Watching his dad at the head of that table, carving the roast, telling his stories about the French Quarter, puffing away on his cigar after the meal—sending up regular clouds of smoke, like a miniature train locomotive—Bud felt himself shaking off a sort of slumber too. After supper he found on the radio some of the Latin music that he liked, and he began to imitate the Cuban dancers—braiding his steps as fast as lightning with his arms crossed in front of his face, snapping his fingers, and spinning his head left and right. He meant it as a joke—but then when everyone quieted and began to watch him, he started playing off the beat of the claves, stalling then rushing the tempo. When he was done, they laughed, but he could see that he’d impressed them too with his witty interpretations. Walter offered him a nickel to dance again.

After Ethel gave birth to Charmaine, things started to change. His parents began talking in Creole all the time, so that he and his sisters couldn’t understand them. When his mother took care of the baby, sometimes Bud would catch her just staring at Charmaine’s face for minutes at a time. Then one day Ethel came home with her hair tamed into neat waves and a new set of clothes, which she referred to as her traveling outfit. She explained that they were going away for a while.

“But where?” Bud asked. “When are you coming back?” He worried that his father’s newfound vitality would disappear with them. Ethel promised to write when they got settled and that Bud could come visit soon. Then she knelt down and hugged him hard, saying, “You’ll understand when you get older.”

He still remembers the day that they left. His dad wanted to take a picture of Ethel—usually he made everyone go up to the rooftop because he didn’t think there was enough light on the sidewalk—but Ethel said there wasn’t time. Besides, she didn’t want to soil her traveling outfit by climbing up to the dirty roof. His father became insistent, nearly yelling that he wasn’t going to have his only photo of his eldest daughter ruined. Finally they compromised by walking to the street corner, where at least they weren’t under the shadows of the buildings.

His father was right—the picture didn’t get enough exposure. Ethel’s face under her hat lies half in darkness. Her skirt blurs with movement, as if she has already begun to walk out of the frame. Sometimes Bud would take the photo out from his mother’s drawer and try to read his sister’s expression. Had she already made up her mind to disappear?

By that time Bud was aware that life was easier for people who lived as white, but he couldn’t understand why Ethel should have to move across the color line so absolutely. They didn’t even know where she was, whether she was alive or dead. No one would think anything if they saw her with him, or with his father or mother for that matter. It was almost as if she was ashamed of them, as if she believed all the things “they” thought about Negroes.

The Italian guy has gone. Bud needs to go too. “Don’t make this so complicated,” he thinks. “It’s just a slip of paper.” He closes his eyes and asks himself, What are you, Anatole Broyard? After a moment he opens his eyes and on the line following other, he writes in his careful print a faint C.

The clerk is a young woman, just a few years older than Bud. As she looks at the young man standing across the counter from her, she feels her cheeks coloring slightly. He’s very handsome, she notes. Then she sees the corner of his lips raise slightly, as if he knows what she is thinking.

“So Mr....” She pauses, puzzling over his name.

“Broyard,” he supplies, rolling the r’s slightly. “It’s French.”

“Right. I see here that you are from New Orleans, which of course was a French territory.”

He cocks an eyebrow. “Very good. You’d be surprised, Miss...” He glances around her desk area.

“Watkins,” she says, touching her chest. “My nameplate hasn’t arrived yet. I’ve just been here for two weeks.”

“Miss Watkins.” He croons her name, making it his own. “As I was saying, you’d be surprised by how many people don’t know anything about the history of our country. Or maybe you wouldn’t be surprised—you must have met so many different people, working here for even a short time—that you have, as they say, seen it all.” He whispers this last bit.

“Mr. Broyard,” she says reprovingly. “I don’t wish to take up any more of your time than is necessary. If I may...?”

“Of course.” He rests his chin on his hand and stares at her intently.

But she is more flustered than ever. The young man’s efforts to engage her in conversation have turned their interview more intimate than she would like. She frowns at the form, clarifies a few points, makes some addendums, and then says, “About number twelve, color, you indicate C. That stands for...”

“Creole,” the young man says confidently.

She shakes her head, indicating that she doesn’t know what that means. When he doesn’t explain further, she asks, “Is that black or white?”

“Well, what do I look like to you?”

His tone tries for affront, but he doesn’t quite pull it off. The clerk takes his question literally. He doesn’t really look black, but there’s something about him—a slight insolence maybe—that makes her think of Negroes. “Mr. Broyard, I can help you fill out the form,” she says, “but I can’t provide the answers for you.”

“Very well, Miss Watkins. Creoles are from New Orleans. They are descended from the original settlers and date back to before the Louisiana Purchase.”

“And so Creoles are...?”

“French.”

“I mean are they white or black,” she says, resenting the exactitude he has forced upon her.

“Well, they can be either. I myself am mostly white.”

Miss Watkins raises her eyebrows.

“I also have a little Indian blood as well as some”—he pauses—“Caribbean influences.”

“Meaning that you’re colored?”

“Well...”

“Is that what it says on your birth certificate?”

“Yes,” he says quietly.

And the clerk feels like she’s won something, something that she fought hard for, only to discover that she didn’t really want it. She looks down at her desk, ashamed of her own tenacity. She reflects unhappily that the young man must think she’s prejudiced.

She taps her pen on the paper, trying to think. She can’t risk running into trouble with her supervisor before her nameplate has even arrived. She’s lucky to have this job, given all the people out of work. “Well, it’s important for the success of the social security program to try to be as accurate as possible,” she says. She begins to make a check next to negro and then changes her mind and starts to write “Creole” in the space instead. Let them—the powers that be—decide what that meant.

“Miss Watkins,” the young man says, beseechingly. With his confidence gone, he looks his seventeen years. She notices that the shoulders of his jacket stand out beyond his narrow frame, making his head look small and delicate. He must have bought the suit a few sizes too big, to stretch more use from it. Or maybe it was his father’s, borrowed especially for this trip. Life, she knew, was very hard for Negroes.

“Is there a problem here?” Her supervisor is suddenly standing beside her. He nods to the long line that has formed in front of her desk.

“No, sir.” Where did all these people come from? “I was just helping Mr. Broyard complete his form.” She cuts her eyes at the young man.

“And what’s taking so long?”

“We had just a little confusion on number twelve. Mr. Broyard is Creole, which are the group, as perhaps you know, who originally settled Louisiana. They were there since before—oh, what did you say?” She glances at the young man for help.

“Miss Watkins,” the supervisor admonishes, “the Social Security Administration is not in the business of conducting genealogical surveys. This gentleman’s color is white. That’s as plain as the nose on your face.” He turns to my father standing at the counter. “I’m sorry, sir, for the delay. I’m sure Miss Watkins’s overzealousness can be explained by the fact that she is new and therefore eager to prove herself.”

The supervisor looks on as the clerk scratches out “Creole” and makes a check next to white on the young man’s application. On the top of the form, she records the next available social security number and then fills out the card for the fellow to keep. She hands it over, mumbling an apology, and the young man with a wave of his hand indicates that all is forgiven. After he has turned to go, Miss Watkins places the young man’s application in her outbox to be sent to the main office in Baltimore and gestures for the next person on line to come forward.

Of course I don’t know what actually transpired in that social security field office to explain the cross-outs and mysterious C that constitute my father’s answer to question number twelve. It looks to me as if a different hand made the check next to WHITE—likely the same person who made the other corrections on the form. But there’s no way to be certain. The original application was destroyed in the 1960s, after its image had been filmed for storage—not in a dusty file room but a defunct salt mine in Kansas, chosen for the aridness of its environment.

I doubt that my father walked away feeling that he’d redirected the course of his life. Unlike his half sister Ethel, my father continued to travel back and forth across the color line—journeys that were often unconscious and inconsequential. As he came to be defined more and more by his intellect, the fact that he was part black became less and less important to him. By extension he made it unimportant to everyone else—or to his white friends at least.

According to Flora Finkelstein, their crowd of aspiring intellectuals didn’t think of my dad as a black student or a white student, just a bright one who was a talented writer. In the late 1930s, there weren’t enough blacks at Brooklyn College to create anything like racial conflict. The factions of communists dominating the cafeteria were eager to demonstrate their solidarity with Negroes and would have happily embraced my father as a comrade-in-arms had they known about his background. But most people didn’t know, because my father didn’t tell them and they didn’t guess it on their own.

“If someone came up to me in the course of my being there and said, ‘Did you realize that Anatole Broyard is part black?’ I would have said, ‘You’re crazy,’” observes Pearl Bell. “I also would have said, ‘Why is this important?’ [Race] just didn’t have the enormous significance that it came to have later on in the sixties.” The poet Harold Norse, who edited the college literary magazine and was a friend of my dad’s, insists that my father couldn’t have been black. “He didn’t look black,” Norse says. “Besides there weren’t any black students at Brooklyn College back then.”

Well, none who registered on Norse’s radar. But among the small number at the “black” lunch table was at least one fellow who knew the details of my father’s background quite well. My dad’s best friend from childhood and the brunt of his teasing, Carlos deLeon, started Brooklyn College in the fall of 1938, six months after my father’s trip to the social security office. When deLeon spotted my father in the cafeteria, he went up to say hello, but my father took him over to a corner and said: “I didn’t tell you, but I’ve decided that I’m going to be white.”

When I reached him by phone in Cleveland, Dr. deLeon—he became a psychiatrist and a professor at Case Western Reserve medical school—was in his late seventies. Age and health problems made his conversation difficult to follow (Dr. deLeon has since passed away), but his bitterness about this long-ago slight from his childhood friend was unmistakable. Harder to decipher was the rest of the story. Dr. deLeon also said that my father avoided him because he thought that Carlos was stupid. “But I graduated at the top of my class at medical school,” he insisted. “And I have many white friends.”

To gain admittance to Brooklyn College in those days, Dr. deLeon had to have been bright, but he excelled in courses like math and chemistry. He wasn’t literary like my father’s new pals, which may explain in part why my dad was reluctant to welcome Carlos to his lunch table. But Dr. deLeon interpreted his rejection as a judgment against his intellect—those childhood spelling games left a deep impression—and then further extrapolated that my father had reached this conclusion because Carlos was black.

That Dr. deLeon linked his racial identity to assumptions about his intelligence wasn’t simply paranoia. After he graduated from medical school in 1946, deLeon was interning for a black doctor located down the block from my father’s family’s apartment. By this time my dad had moved to Greenwich Village, but he bumped into Carlos outside the doctor’s office during a visit home. My dad said to him, “What the devil are you doing in a white coat with a stethoscope around your neck?” And Dr. deLeon answered, “Well, man, what would you think if you saw anyone else with a white coat and a stethoscope?” It was a reasonable question.

If my father believed that being black held a person back—because of the general limitations imposed on the race, such as job discrimination, or the specific ways that being black hindered a person’s development, such as inferior schools and lower academic expectations—then he could feel better about avoiding a black identity himself. But African Americans who succeeded despite these obstacles forced him to rethink his equation. Was my father unwilling to claim a black identity because he simply refused to go along with the prevalent notion that blacks and whites were different in an essential way? Had the confusing racial climate of his upbringing left him feeling racially neutered? Or had he to come to believe what “they” thought about black people: that they were necessarily inferior?

Was my father’s choice rooted in self-preservation or in self-hatred? Did it strike a blow for individualism or for discrimination? Was he a hero or a cad? And how did he justify his behavior to himself?