During the first half of the twentieth century, Greenwich Village became a haven for writers and artists. With Midtown executives and Wall Street bankers to the north and south, and New Jersey factory workers and Brooklyn shopkeepers to one side and the other, that square mile in lower Manhattan provided refuge from the daily grind of dollars and cents. As my dad’s friend Milton Klonsky put it, “The Village, with its unpredictably digressive streets and twisting free-associational byways, was divided from the straight and square-away world uptown like the ego from the id.”

In the Village, a cold-water flat could be had cheaply. Barkeepers let a person sit for as long as he could nurse a beer. A ten-cent plate of spaghetti and meatballs from the Waldorf Cafeteria on Sixth Avenue could fend off hunger for most of the day. Among the artists and writers who hung out in the San Remo Bar, the Cedar Bar, and the Minetta and White Horse taverns, conversation was the only currency that mattered.

Nobody cared where a person was from; nobody asked about your family. They wanted to know what you thought—about Freud, Surrealism, the Modernists. Had you been to Paris?...Were you in analysis?...What did you make of the Stevens poem in the latest Partisan Review? Everyone in the Village had run away—from conventional backgrounds and burdensome family histories, from petty lives short on grandeur and futures that would leave them as normal and discontented as everyone else. It was in Greenwich Village that my father could figure out the person he most felt himself to be.

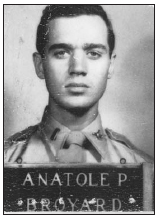

It would be a while, however, before he made it across the river. The same fall that Hitler invaded Poland, my father dropped out of Brooklyn College, explaining to his friend Vincent Livelli: “It doesn’t coincide with my frame of mind.” The college administrators may also have encouraged him to leave. His grades had never risen above Cs and Ds (except for one B in Hygiene). Vincent doesn’t remember ever seeing him carrying books or studying. “I don’t think he was very serious about college,” he says. But my father continued to hang around the campus in his spare time, and one day he noticed a pretty girl and struck up a conversation with her. Her name was Aida Sanchez and she was Puerto Rican, which made her almost as much of an outsider at Brooklyn College as he was. Before long Aida replaced Flora as my father’s constant companion.

While today there’s much cross-pollination—cultural and otherwise—between Puerto Ricans and African Americans, that wasn’t the case in 1940. The Puerto Rican migration to the United States had barely begun, and the new immigrants didn’t tend to settle in black neighborhoods. Shirley says that her parents didn’t know what to make of Aida when Bud brought her home for dinner, figuring only that she was an extension of his obsession with Latin music. But in fact Aida’s family and the Broyards had more in common than any of them realized.

Like that of New Orleans, Puerto Rican society during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was characterized by three distinct racial groups: whites, slaves, and free people of color (which included the native Indian population), with much blurring of the boundaries between them. As a result the majority of Puerto Ricans were mixed, but the absence of Jim Crow laws meant that black and white identity had never been measured in blood as in the United States. Class dictated a person’s side of the color line.

In the United States, Puerto Ricans, and Hispanics in general, remained outside the one-drop standard applied to mixed-race African Americans. For example, up until 1960, census enumerators were instructed to record mixed white and black people as Negroes no matter how small the black component. Hispanics, on the other hand, were generally classified as white unless their appearance was too black for the enumerator to ignore.

For my father’s friends in Bed-Stuy, his decision to marry Aida marked the beginning of his living as a white man. Indeed, both he and Aida described themselves as white on their marriage license. When I track down Aida in a nursing home in Los Angeles, she says that my father wasn’t being dishonest. She describes the pale skin and wavy hair of her former in-laws, insisting that there was very little black in the Broyard family. Aida has a daughter with my father, which might explain her reluctance to acknowledge his African ancestry. Also, by the standards in the Puerto Rican community, my father was white.

My father used to say that he married Aida because with the war around the corner, everyone was getting married to have someone to write home to. Shirley suspects that her brother may have also wed and impregnated his wife as a way of avoiding going to war altogether. When I ask Flora Finkelstein what she made of my father’s decision to marry Aida, she says simply, “Well, she was very beautiful.” Aida was vibrant, smart, and fun too. But it’s also true that marrying a Puerto Rican woman was a way for my father to postpone committing to a specific racial identity. For a mixed-race person, the choice of a mate is often viewed as an indication of the world—black or white—in which a person locates him- or herself. Whenever I tell my aunt Shirley I’m dating someone new, she asks about the fellow’s race. I imagine that an answer of black would convince her that I’d truly embraced my African American heritage.

While Aida defended my father’s subversion of his racial identity, she wasn’t so happy about the rest of his unconventional behavior. After finding them a cold-water flat on Gay Street in Greenwich Village, he painted a love poem that he’d written to Aida on the bedroom door, but on most nights, he could be found out dancing with another girl in his arms. During the daylight hours, when he wasn’t working, he spent his free time studying art at the New School, browsing the bookshops along Eighth Street, or arguing the relative merits of Baudelaire and Mallarmé in a café. Six months after the couple wed, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States entered the war. It wouldn’t be long before my father was drafted, and he didn’t intend to spend what little time he had in the Village staying home with his new bride.

After Aida became pregnant, the couple moved in with my father’s parents to await his orders to ship out. Six months before their daughter was born, my dad headed off to basic training at Camp Edwards in Massachusetts, as a white man. By then checking off that box was getting to be old hat. Or perhaps, as happened with his buddy Harold down the block, the clerk at the draft board simply looked at him and marked him as white without my father having said a word. As a white man with some college, he was tapped for officer training school, and in a twist of fate that would help to set his course on his return, my father was placed in the command of a Negro stevedore company.

More than 1 million African Americans served during World War II, but they were segregated from their white counterparts for much of the war. Overwhelmingly, black servicemen were assigned to noncombat roles: they cooked meals, drove trucks, and loaded and unloaded ships, like the men in my father’s company. Aside from the famed Tuskegee Airmen, few units saw any action.

In the war stories that my father occasionally told, he would mention that he’d commanded black troops. One time I asked him why—I had the sense that the assignment was unusual—and he said that his senior officers must have figured that as a city boy, he was better able to understand them. Ironically, this answer may not have been so far from the truth.

A few black units had black officers, but the majority were led by white men. Part of the problem was logistical: at the beginning of the war, there weren’t enough existing Negro officers to supply the necessary command—only five in the army in 1940, three of whom were chaplains. The military also had a longstanding bias that blacks didn’t make good leaders. But the War Department soon discovered that white officers didn’t effectively lead black troops either.

Initially the department followed a policy of tapping white southerners to command black units, with the rationale that these men had more experience with the race. Not surprisingly, many of these white officers resented being assigned to a Negro unit. Not only did maintaining segregation impose extra duties, but discrimination in the world at large meant that black soldiers entered service with less education and technical preparation than their white counterparts, which made training them more difficult. And then some white officers were simply prejudiced. Fairly typical was the opinion expressed by this commander when writing to a friend that black soldiers “are for the most part afraid and the few smart ones have no desire to fight.” Another officer seeking transfer to a white unit described his “disgust for [black soldiers’] inherent slovenliness, and their extreme indolence, indifference and frequent subtle insolence.” Of course, these attitudes didn’t exactly encourage confidence in their leadership among the black soldiers. Neither did the constant turnover, from all the white officers who managed to get themselves reassigned.

By 1942 the War Department realized that morale in the black units was abysmal and set about trying to improve the caliber of their commanders. When my father was assigned to the 167th Port Company in Noumea, New Caledonia, in March 1945, the department had implemented standards for officers of Negro units. They were supposed to possess demonstrated leadership ability, along with evidence of maturity and patience. Efforts were made to ascertain whether an officer would be amenable to working with black troops, either through personal interviews or by reviewing the candidate’s personnel file. For the previous three years, my father had been a drill instructor stateside and then a troop commander for an antiaircraft unit stationed in New Guinea. This experience, along with the fact that he’d grown up in New York City—perhaps he even mentioned living in a mixed neighborhood—apparently qualified him for the assignment.

The French colony of New Caledonia, after throwing off Vichy rule early in the war, became a staging area for American operations in the South Pacific. My father was hardly off the boat before he began trying to chat up some of the native women who were hanging around the dock, quoting lines in French from Baudelaire. To the amusement of his new fellow officers, these women, who were mostly prostitutes, burst into laughter, and my father’s nickname Frenchy was born. The long workday didn’t leave much time for extracurricular activities. My father and the other lieutenants served ten-hour shifts, overseeing the crews of black stevedores as they loaded and unloaded ships.

Two of my father’s fellow officers remember my dad having some trouble getting the black soldiers to take his orders. Normally the company was run like a combat unit, with orders passed down through the chain of command. When an officer wanted a ship unloaded or a truck moved, he relayed instructions to a sergeant, all of whom were black, who then got the enlisted men to execute the order. This system, explains Edward Howard, who was a second lieutenant like my father, limited opportunities for the noncoms to regale the commanders with their complaints. “Because as long as they were talking, they weren’t working,” says Howard. Receiving orders from other blacks also helped to keep the morale high. Ellis Derry, who’d been a first lieutenant in the 167th, tells me that not all companies ran as smoothly. In another port company, the white officers were forced to go around armed.

One day not long after my father arrived, First Lieutenant Derry received word that the men had gone on strike and were refusing to work. When Derry arrived at the dock, he found all the stevedores hanging around on top of the ship and the new officer, Second Lieutenant Broyard, leaning on the gunnels alongside them.

Derry approached one of the black sergeants and asked him if he was planning on working that day. The sergeant had to say yes or risk being court-martialed. When Derry told him to get into the hold, the sergeant tried to protest that no one else was down there, and Derry said, “I didn’t ask you if there was anyone else there or not, I told you to go to work.” The sergeant went into the hold, and after a moment the rest of his men followed.

Derry attributes this episode to my father’s inexperience in commanding black troops. But I wonder. It hadn’t been so long ago that my father was being chased through his neighborhood by gangs of darker-skinned boys. Some of his men may even have suspected his black ancestry—his curly hair and tawny skin, a certain ease my father had around blacks, or his slightly “pimp roll” style of walking—which could lead them to make subtle challenges. It’s possible too that my dad heard out their complaints because he knew firsthand that blacks received a bad deal and he felt compassionate toward them. Unfortunately I haven’t been able to track down any of the soldiers who were under my dad. The records for individual military units only contain the names of officers, and, unlike many whites who served in World War II, the stevedores weren’t inspired by their experiences to hold regular reunions.

For African Americans who didn’t grow up under Jim Crow, military service was often their first experience with formalized segregation. During his time with the 167th, my father had a chance to witness such humiliations up close. He would have heard the kinds of remarks that whites felt free to make when blacks weren’t around. He would have seen black soldiers barred from entering USO clubs by armed white soldiers. While his fellow officers in the 167th seem to have genuinely respected their black enlisted men, there was no getting around the fact that simply because of their race, the whites gave the orders while the blacks sweated in the ships’ hold beneath them.

Novels about racial passing often feature a pivotal scene where the light-skinned protagonist witnesses some mistreatment of blacks that convinces him or her to cross to the other side. In James Weldon Johnson’s The Autobiography of an Ex–Coloured Man, the narrator decides after watching a lynching that he will never again identify with a group of people who could be treated worse than animals with impunity. I wonder if my father saw something during his time with the 167th that helped him make up his mind about how he would live his life when he returned to New York.

Was he there on that scorching day when the men were unloading a freighter that was anchored offshore? At break time the black men headed for the ship’s water fountain—they’d been working for four hours in a hot, cramped hold—where they were met by a white crewman armed with a loaded pistol. Ignoring the demands of the presiding officer, the man prevented the stevedores from getting a drink for hours, until the Coast Guard finally arrived to arrest him.

There was also the story that my father told about the black soldier who suddenly went crazy and slashed open another enlisted man’s belly with a jungle knife. The perpetrator fled into the woods, with my dad—so he told my brother and me—right behind him, in hopes of reaching the deranged man and convincing him to give himself up before the white guards got to him. As my father ran through the forest, did the shouts of “catch that crazy nigger” make him fear for his own life? I have no way of knowing.

While my father’s service in the army probably made him feel more distanced from blacks than ever, I suspect that it left him mostly determined to live outside a world where roles were predicated on race, because he didn’t necessarily draw any closer to white soldiers. He told another story about sitting on the ship’s deck very early one morning during a transpacific crossing. With his arms hugged around his knees, he stared onto the ocean, adrift in the loneliness of being surrounded by a thousand strangers. A shipmate walking by commented, “Feeling anthropomorphic this morning?” My father nearly jumped up and hugged him—he was so grateful for someone who could recognize his “existential absurdity.” (He discovered later that the guy was being discharged on a Section Eight; he was considered crazy.) But for the most part, my father didn’t know anyone who could remind him of the person he’d been at home.

Instead he had a collection of poetry by Wallace Stevens. One night while standing watch on the dock in Yokohama, my father began reciting all the lines he could remember—“The windy sky cries out a literate despair,” “These days of disinheritance we feast on human heads”—and the idea suddenly hit him that when he returned stateside, he’d move back to Greenwich Village and open a bookstore.

The question of what he would do had suddenly become real. It was the fall of 1945; the United States had dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Japan had surrendered. In Yokohama the weather had turned cold, and much of the city was bombed into rubble. The Japanese who were left wandered the streets, their remaining possessions tied to their backs in filthy blankets.

As my father watched his men unload pallets of milk, he pictured a secondhand bookstore, specializing in twentieth-century literature. The idea made him feel warm, and he took his hands from his pockets and squeezed them. In a few months he would be back at his parents’ apartment in Bedford-Stuyvesant, biding his time until the rest of his life began.

The Broyards’ household had changed since my dad went overseas. Aida, who had been living with Nat and Edna, moved out, taking her and my father’s baby daughter with her, after intercepting some love letters from an American nurse that had beaten my father home on a different Liberty ship. She might have forgiven him if he hadn’t been so determined to open the bookstore. Aida wanted her husband to get a job in an office, with a dependable salary. “I loved Anatole,” Aida tells me, “but my mother convinced me that I would never be happy with him.” The couple filed for divorce a few months later. (In a few years, Aida would remarry and move to Texas, where her daughter would grow up calling a different man father and never meet her biological father’s second family.) In the meantime Shirley and her new husband, a young NAACP lawyer named Franklin Williams, had moved into the apartment upstairs.

My dad spent his days canvassing Greenwich Village for a place to live and a space to open his bookstore. Vacancy rates hovered near zero immediately following the war, making an affordable rent hard to find. At night he was back in class at the New School. But on the weekends, he joined his family for dinner. Shirley says that she doesn’t remember anything unusual about those meals, but I can’t imagine that conversation came easily.

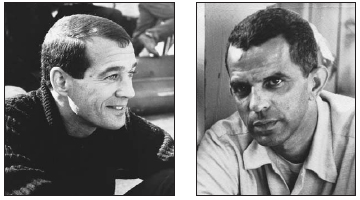

My father and his brother-in-law actually had a lot in common. Both men were bright and handsome, which made them a little arrogant, and they could be extremely charming. Each thought of himself as special—someone for whom the regular rules didn’t apply. My father and Frank even looked a bit alike, with the same close-cropped hair, tall forehead, and deep, penetrating eyes.

Frank also grew up among middle-class blacks. He lived in a big brick house in Flushing, Queens, that belonged to his uncle, the first black doctor in the borough. Frank was raised mostly by his grandmother, who was very light-skinned and looked more American Indian than African American, which initially confused him about his family’s identity. He used to tell a story from grade school about the time that the teacher asked all the students about their background. One kid said that he was Irish from Ireland; another answered that he was Polish from Poland. When it was Frank’s turn, he said that he was an Indian from Indianapolis, which was his grandmother’s hometown.

By the time Frank met Shirley, however, he knew exactly who he was: a black man who was dedicated to the betterment of his race. And he couldn’t understand how any thinking African American wouldn’t feel the same way.

Frank and Shirley had been living upstairs from the Broyards for a year and a half when my father returned from the war. By this time Frank had grown used to the family’s ambivalence about their racial identity. He knew that his father-in-law didn’t approve of him, because Frank was too dark and too insistent about being a black man. Because Nat had spent his first thirty-eight years in the South, Frank might have overlooked some of his father-in-law’s old-fashioned attitudes, but Shirley’s brother didn’t have that excuse.

I can imagine the scene of my father’s arrival home. In his letters he has complained to his parents about ruining his teeth from a diet of candy because he couldn’t stand the army food. Edna has spent the morning in the kitchen, where she prepares all his favorite dishes: roast chicken, mashed sweet potatoes, string beans, and fried banana fritters for dessert. Nat picks up some Rheingold beer and a copy of the New York Times.

Frank knows from Shirley that Bud served in the army as a white man. But he’s also heard about his brother-in-law’s sophisticated taste in literature, his love of jazz and French films, and his skill on the dance floor. Bud has stirred this family from its somnambulistic existence, and Frank can’t resist getting caught up in the excitement of the return of the prodigal son.

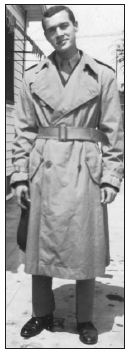

Everyone admires how handsome my father looks in his officer’s uniform, although Edna insists that he’s grown too skinny. In Bedford-Stuyvesant, there are a lot of young men in uniform, but not too many with officer’s insignia on their sleeves.

When Bud sees the spread of food, he teases his mother that she’s made enough to feed the entire army. And he adds how if only she’d been cooking for them, they’d have won the war long ago. Edna hugs Bud again before scurrying back to the kitchen. Shirley introduces Frank, and the two men shake hands with a decisive grip, as if they are boxers greeting each other before the opening bell. Nat opens a beer for Bud and offers a toast to “the veteran.”

Over dinner my father tells his war stories. The one about taking a ride in a fighter with a friend and coming upon a Japanese warship. Seated in the bomber’s position, he razed the deck with machine-gun fire. He tells them how the men looked like ants swarming the ship, which made it easier to squeeze the trigger. And then there’s the story about the crazy guy who slashed open the stomach of another stevedore, and how the victim caught his guts as they fell out into his hands. Maybe Shirley or Edna objects that this isn’t dinner table conversation, but my father goes on, explaining how after the soldier was sewn up and the wound was healed, the doctor removed the bandage, taking the man’s belly button with it. My father laughs a little condescendingly, recalling that the soldier had become hysterical and wouldn’t calm down until the doctor promised to reattach it. My father subtly indicates the stevedores’ race by imitating their voices or mentioning a detail about hailing from rural Georgia. Frank watches his brother-in-law for some recognition that he also has roots in an African American community, but my father gives away nothing.

Frank also has some war stories he could tell. He might start with his arrival with some white friends at Fort Dix for basic training, where he was separated from them and made to line up with the other black soldiers. It was his first experience with formalized segregation, and from then on Frank could sense his white friends’ acceptance of the new racial order. He could have told his wife’s family how he arrived at his camp in Arizona to find that the black soldiers had to sleep in tents, while the white men were housed in barracks. After a few weeks of marching in circles and cleaning toilets, he realized that the fort was nothing more than a holding pen. The officers, all white southerners according to army policy, had no intention of letting the black men fight, lest proving themselves on the battlefield might lead them to expect equal treatment at home. But this kind of talk—political, indignant, racial—wouldn’t be welcome at the Broyard table.

At the end of Frank’s life, Enid Gort, a colleague and close friend, recorded his oral history in preparation for writing his biography. She tells me that Frank gave her the impression that he could pick up the phone and call his brother-in-law anytime he wanted, but because Anatole wasn’t interested in civil rights, they had nothing to talk about. “There was a lot of tension there too,” adds Enid, “that started with a sort of unspoken competition when they were young.” I can imagine Frank silently fuming at the dinner table as he watched my father receive the hero’s welcome befitting a returning first lieutenant—all because he’d passed as white. (In the war stories he told my brother and me, my father returned home with a captain’s rank, another example of his bending the truth.)

If my father felt embarrassed or self-conscious in front of Frank, he didn’t show it. During their rare interactions, he was always friendly with his brother-in-law, but in private he referred to him as a “professional Negro.” Had they ever discussed their views on the race question, the men might have agreed that blacks shouldn’t accept being treated as inferior. But unlike my dad, Frank didn’t have the choice to opt out. He had to try to change the system instead.

During the three years that my father was stationed overseas or on the West Coast, his childhood neighborhood had deteriorated significantly. In 1944 the health districts were redrawn, and Central Brooklyn officially became Bedford-Stuyvesant. A few years later, the Brooklyn Eagle sealed the neighborhood’s fate as the bastard child of the borough with its declaration that Bedford-Stuyvesant was “one big, continuous slum, largely populated by Negroes.”

The decline of the neighborhood gave my father one more reason to escape. After months of searching for a place in Greenwich Village, he finally met a woman at a party who told him that she had two adjacent apartments in a tenement building on Jones Street, and that one of them might be available. The woman, Sheri Martinelli, was an abstract painter and a protégée of Anaïs Nin’s. The next day, when my father went to see the apartment, he found it jammed full, with an old printing press and piles of canvases, half-empty boxes, and clothes. Confused, he turned to Sheri and asked if the apartment was available. The way she smiled at his question led him to understand exactly what she was offering. “I’ll take it,” he said, meaning, of course, that he’d take her.

My father went home, packed his things, and kissed his parents good-bye. They didn’t know what to say. Since he’d returned from the army, Nat and Edna had been treating him differently—calling him Anatole instead of Bud, asking no questions as he came and went at odd hours. When he told them he was moving out, they simply said, “You’re a veteran now,” as if his war experience had turned him into a stranger. As his taxi pulled away, Nat and Edna stood waving on the curb. Although he was only moving across the East River, a sense of finality marked the occasion. Nothing had been said out loud, but everyone understood that my father was embarking on a new life. His parents must have wondered if that meant that he, like his half sister Ethel, would disappear from their lives forever.