Two years after they were married, my parents moved from New York to southeastern Connecticut, where they bought and sold a series of antique farmhouses over the next twenty-five years. The house where my parents were living when I was born had been a tavern during the American Revolution—the curved wooden bar still stood in the front room—and George Washington was supposed to have stopped there for a drink. All of these houses had a central “keeping room” with an oversize stone fireplace that provided heat, light, and fire for cooking. Over the years my mother acquired the hearth and kitchen accoutrements that a colonial family would have used: a big black cast-iron pot, a row of wrought iron spoons and forks, bellows, a butter churn, and a long wooden paddle to remove the bread from the beehive oven. When I was little, I would pretend to cook in the fireplace and imagine that we were Pilgrims trying to make our way in a foreign land.

Indeed my parents had come to Connecticut as hopeful settlers, looking to secure for their children a contemporary version of the American dream. When my mother was pregnant with my brother, they bought a ten-room house with a pool and a tennis court in a rural neighborhood, miles from any friends or family. The exceptions were Robert Pack, a Barnard professor and Wallace Stevens scholar who played in my father’s weekly volleyball game, and his wife, Patty. My parents’ social life consisted of having dinner with this couple every Wednesday night at alternate houses.

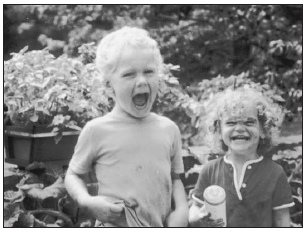

But then in July 1964, Todd was born, providing reason for their self-imposed isolation. By this point my mother had asked my father about his racial background. He’d mostly evaded the question, saying something vague about “island influences.” But my mother had gotten to know Lorraine—the three of them traveled together in Europe for three months the previous summer—so she didn’t have reason to feel that my father was hiding his family. If either of my parents had any lingering apprehension about how a baby would come out, my brother’s appearance must have put them at ease. Towheaded, blue-eyed, and pale-skinned, he looked like a pre-Raphaelite angel. Two years later, I arrived, with more of my father’s darker coloring, but not so much to make anyone wonder about my ancestry.

My father may not have thought of the move to Connecticut as a conscious decision to pass as white, but it did settle the question of which side of the color line his children would be raised on. While the fact that he was mixed race was common knowledge in New York, the rumors didn’t follow him outside the city. In Greenwich Village he had never seemed bothered, or even aware, that people were gossiping about his background, but once my brother and I were born, the stakes were higher. Part of Connecticut’s appeal might have been the unlikelihood that we’d accidentally discover the truth. It was also, in my parents’ opinion, a wonderful place to raise a family.

My father had been greatly looking forward to having children—fueled perhaps by regrets over his neglect of his first daughter—but he was unprepared for the depth of his feelings for my brother and me. He told a friend: “You think you’ve been in love in your life, and then you have children, and you realize that you’ve never really been in love before.” Like any parent he wanted us to be happy. And it seemed, from what he said to my mother and various friends over the years, that he thought living in Connecticut and living as white were our best shot. With rigorous schools that combined high expectations and mollycoddling to coax forward our best selves, wide-open spaces in which to exercise our growing bodies and exhaust our youthful spirits, and neighbors whose friendships could one day prove beneficial, our exurban life offered all the advantages that my dad’s upbringing had lacked. Yet my father still indulged a predilection for viewing our childhood as marked by narrow escapes.

When we were young, he would entertain vainglorious fantasies of rescuing us. The scenarios he concocted were usually far-fetched: he’d yank us at the last minute from the path of a Bengal tiger or snatch us out of the surf, away from an incoming tidal wave. He seemed to view the role of father as a kind of homespun Superman.

He reveled in the physicality of the job. My brother was a colicky baby who required constant motion to keep him from fussing. My dad happily rocked him for hours on end, even playing tennis in the afternoons with his racket in one hand and Todd’s carriage in the other. He delighted in parading me through the house after my bath, seated naked on his large palm, perfectly balanced, like a waiter with a tray.

The games he played with us involved small, exhilarating risks. We would toboggan down a rarely used country lane that led into a busy intersection. Near the end of the ride, my father would leap out of the sleigh and stop it before it ventured too close to traffic. Or we would run down a blanket chest that he’d placed like a diving board at the foot of my parents’ bed and fling ourselves torpedolike at our father, who sat against a barricade of pillows piled against the far wall. Every time he would catch us in midair.

By saving us, could he begin to save himself? By appearing heroic in our eyes, could he feel more like a hero? I suspect so. Just as he’d managed to divert the outward signs of his black ancestry with the infusion of my mother’s Nordic blood, he could deflect the inward turmoil he’d felt growing up through providing us with a childhood of “ideal experiences.”

What my father didn’t seem to realize was that the world was changing. Being black or mixed race when my brother and I were growing up wouldn’t have marked us with social inferiority the way that it did in the 1930s. But out in Connecticut, snug in our antique farmhouse, the clocks might as well have been turned back a generation or two. The evolution in civil rights that was rocking the country didn’t upset life along our country lane. Given that blacks made up less than 5 percent of the population in Fairfield County in the 1960s (and most of them lived in Bridgeport), it was almost possible to put African Americans out of one’s mind entirely if it weren’t for the nightly news.

In 1963, the year that my parents left the city, image after image from the civil rights movement scrolled across the television screen every evening: water hoses and attack dogs turned on black teenagers in Birmingham, Alabama; Martin Luther King Jr. leading hundreds of thousands of men and women in the March on Washington; four little girls killed by a bomb in a church basement. The following summer the focus moved closer to home, with riots sweeping through Harlem and Bed-Stuy following the fatal shooting of a black boy by a white police officer. If my father tuned in to these events, he didn’t talk about them, and despite the fact that some of it was taking place on the streets where he grew up and his mother still lived, he never gave any indication of relating them to his own life.

Martin Luther King, lunch counter sit-ins, protests and marches—my father didn’t like any of it. He was opposed to turning race into a movement that collapsed affiliation and identity, requiring adherence to a group platform rather than to one’s “essential spirit.” While many African Americans would argue that the civil rights movement was a bid for recognition of the Negro’s humanity—after all, one of the most popular picket signs was “I am a man”—my dad only saw the ways that such collective action could become an avenue of flight, distorting a person’s sense of self.

In the late sixties, Michael Vincent Miller began to notice an edge in my father’s attitude about race that hadn’t been there before. My dad started regularly using terms like “spade” and “jigaboo” and making derogatory comments about black people. Another friend from that era and his future colleague at the Book Review, the novelist Charles Simmons, later hypothesized that this stance was ironical on my father’s part—almost a way to test the listener’s own racial attitudes. But in hindsight Mike understands it more as a reaction against the rise of black nationalism.

Black pride certainly complicated my father’s already fraught relationship to his racial identity. On the one hand, it made his ambivalence about his background seem misplaced and embarrassing, leaving him the lonely defender of a debunked position. On the other hand, the movement narrowed the acceptable ways that my father could be black, if he had been encouraged by the advancement of civil rights to head in that direction. Anything short of growing an Afro and donning a dashiki might not have measured up.

Mike suggests that my father found the African American identity that emerged during the Black Power movement sentimental and false. After all, for his entire life, he’d been against their basic principles—that blacks were and should be different and separate from whites. “He wasn’t racist as much as he was opposed to a certain liberal embracing of an idea of blackness that struck him as inauthentic,” Mike observes.

Indeed my dad was particularly put off by the way white liberals had taken up race as their cause. Kit Blackwood, who dated my father in the late fifties, remembers telling him how bad she felt about the state of affairs for black people in New York and that she wanted to find a way to help them. Growing up in Texas, she’d been mostly raised by her family’s black housekeeper, which had sensitized her to racial injustice. Since she and my dad had talked openly about his background—he’d even introduced her to Lorraine—Kit expected him to encourage her impulse, but in fact he’d come down hard on her. “He said, in essence, that white people don’t understand and they should stay out of it,” she recalls.

Luckily for my father, people didn’t tend to move to Cheever country to proselytize for progressive causes. They came to wrap themselves in the safety and comfort of bourgeois trappings. Of course this good life required money.

After Todd was born, Greenwich Hospital wouldn’t release him until my parents paid the bill—$500, which they didn’t have. My dad’s advance for the novel was long gone, and my mother had been swindled by a dishonest uncle out of her inheritance from her grandmother. What little she could access from her father’s estate had been used for the down payment on the house. If my mother asked her siblings for the money, it would only confirm their suspicions about my father’s inability to provide for their little sister. My dad called a friend from the Village, Albie, who was a jewel thief and always seemed to have a lot of cash on hand. When telling this story later, my father would portray Albie as a Robin Hood figure: he took from the rich and gave to the poor. That was us, the poor, living in the big house with the pool and the tennis court.

After bailing out my mother and brother, my father took the train back into the city and got his first full-time job, as a copywriter for a New York advertising agency. To the shock of his old friends, he stayed for seven years, working on accounts of Time-Life Books and Columbia Record Club. Anatole, the consummate Village bohemian, had become a company man, a daily commuter! But as the pal of his novel’s narrator said, “Your life is there and you live it.” Which didn’t leave much time for anything else.

During my father’s first year in Connecticut, away from the diversions of the city, he managed to produce more writing than he had in years. Living an ordinary life could be fruitful. He published a story in Playboy and another one in the New Yorker, and wrote a handful of new chapters for the novel. But that period of productivity soon ended, and my father found that he had traded in one set of distractions for another.

During the summer months, he convinced Tim Horan, his boss at the ad agency, who’d read his fiction back in the fifties and was as anxious for the novel as everyone else, to give him an extra ten days of vacation. “He’d always say that was all he needed, a few more weeks,” Tim remembers. “Then he’d come back and say, ‘Well, I got it pretty well finished. I’ll certainly finish it by next spring.’”

In fact he wasn’t making any progress at all. Going by the dates on his notebooks and drafts of stories, he seems to have ground to a halt not long after he started at the advertising agency. The sustained concentration required to produce literary fiction wasn’t easy to come by for a man with a full-time job, two children, and a house in need of constant repairs—and those weren’t my father’s only problems.

Bob Pack, my parents’ neighbor, says: “At that time, there were two fictions that were a part of your dad’s psychology. One was that he was working on the novel and was going to finish it. The other was the fiction of his white origins.” About the book, Bob, like Mike Miller, guessed that my father had set his standards to a paralyzing height. About my father’s background, Bob says: “The assumption that I made, and everyone else I knew made, was that people are entitled to see themselves the way that they want to. They have the right to make public what they want to make public, and keep private what they want to keep private.” Bob adds that for my father’s friends, his racial identity didn’t make a damn bit of difference.

But it did make a difference for my dad when it came to writing an autobiographical novel with a coming-of-age theme that centered on his relationship with his father. “He didn’t use the word ‘blocked,’ but it was a very painful business,” Miller says. Although Mike never talked directly with my dad about his background, he sensed that unresolved issues concerning my father’s identity were preventing him from gaining the required perspective for his theme.

It was only in my father’s conversation that Mike saw all the aspects of his background coming together: his vast knowledge of European and American literature and his ironic—normally Jewish—take on the world, combined with the raw earthiness of funk and the graceful improvisation of jazz. “If he could have turned this loose in his fiction, it would have been marvelous,” Mike says. “He would have synthesized the best elements of American culture.” But my dad was never able to write with the spontaneous elegance that was in his speech. Something kept making him tongue-tied whenever he faced the blank page.

That my father should feel compelled to make the subject of his novel the one subject in his life that he couldn’t address was the kind of irony that he appreciated. He greatly admired, for example, the idea at the center of Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents: since our human nature makes us want to have sex with everything in sight, all civilizations, in order to prevent themselves from falling into anarchy, must incorporate repressive rules about who a person can and can’t be intimate with. Such tensions demonstrated human beings’ selfish and selfless extremes. But while theoretically fascinating, living within an irresolvable contradiction could wear a person out.

Just as domestic life hadn’t loosened my father’s writing block, neither did it solve my mother’s problems. Her insomnia and anxiety only increased after the wedding. At my father’s suggestion, she entered analysis, a style of therapy that is now understood to be the worst possible treatment for post-traumatic stress syndrome. After suffering a breakdown in the analyst’s office, she only escaped hospitalization through the intervention of a progressive psychiatrist who put her on one of the first-ever antidepressant medications. But in the meantime she’d stumbled on a powerful elixir of her own—bourbon and sleeping pills—that could lift her out of her pain, and consciousness, for stretches at a time. Having babies and fixing up houses kept her distracted for a while, but after a few years in Connecticut, the old nightmares reemerged, and my mother began knocking herself out more and more frequently.

A wife who spent her days wrapped in an old blue bathrobe on the couch in the den, alternately crying or drinking some more until she passed out again, was a Cheeveresque aspect of exurban life that my father hadn’t anticipated. Beyond driving around to the local liquor stores and asking them to please not sell alcohol to his wife, he was at a loss about what to do. Just as he’d tried to avoid the problems of the city by heading to the country, he escaped his troubles in Connecticut by fleeing back to Manhattan, where he took refuge many nights at a pied-à-terre that he rented with a friend. No doubt the women in whose arms my father had always distracted and reified himself offered an additional palliative.

And so while my father may have succeeded in rescuing us from the pain of his childhood, we were left to deal with the pain of our own childhoods by ourselves. It wasn’t until a few years after my mother quit drinking, with the help of some therapists who specialized in trauma, that my dad recognized his misguided belief in the protective powers of the good life. In an essay he wrote in the late seventies for the Times, he wondered if being raised in the country was any better than a city upbringing. The wounds in exurban life “are too exclusive, too internal, too often originating in the family.” Perhaps it would have been healthier for us to have been hurt by the outside world instead.

Yet my parents kept on buying and selling houses in Fairfield County, as if the solution was simply a matter of finding the right environment. And actually the strategy sort of worked. With each new location, they allowed themselves a fresh start; as if struck over and over again by sudden amnesia, they continued to believe in the possibility of happiness. Finally, in 1976, shortly after my mother became sober, my parents moved to the last of their eighteenth-century farmhouses, where we would stay put for the rest of my childhood.

My father had also changed jobs, which helped matters. Since moving to Connecticut, the one kind of writing he’d been able to produce quite successfully was literary criticism. A couple of page-one reviews he wrote for the Times Book Review brought him to the attention of the paper’s cultural editor, Arthur Gelb, when a position for a daily book critic opened up in the winter of 1971. The job was arguably one of the most influential in publishing. Two to three times a week, the daily reviewer’s column could make or break an author’s career. Landing it meant that my father could spend his days doing what he liked best: reading books and thinking about writing. But he nearly took himself out of the running in his eagerness to settle an old score.

A few months earlier, my dad had gotten word that his ex-friend Chandler Brossard had a new novel coming out. Over lunch one day with Tim Horan from the ad agency, my father mentioned that he was thinking of offering to review the book for the Times Book Review. Wouldn’t it be nice if Chandler finally had a hit, my dad had said, which Tim found curious, since he’d heard the story about how the passing Negro in Brossard’s first novel was based on my father. In any case, my father submitted the review long before the book critic position was even on the horizon, though the piece hadn’t yet been published when he learned that he’d gotten the job.

According to Gelb, the competition had come down to my father, the critic Alfred Kazin, and the Irish writer Wilfred Sheed. Neither Kazin nor Sheed particularly wanted it, and my father did. He was also seen as someone who could lend a bit of hipness to the paper’s rather staid image. Kazin later likened my father’s arrival in the Times’s offices to that of an ambassador for Greenwich Village sophistication. After his seven years of commuting back and forth from Connecticut to the advertising agency, it was a role my father was delighted to reprise.

His appointment was announced in the paper on a Monday. The following Sunday his Brossard review finally ran. It began: “Here’s a book so transcendently bad it makes us fear not only for the condition of the novel in this country, but for the country itself.” Within weeks articles appeared in the Village Voice and the Boston Globe denouncing my father for using the Gray Lady as his bully pulpit. The Book Review was forced to devote an entire letters section to the ensuing firestorm: Brossard’s charge, my father’s countercharges, and a chorus of bystanders weighing in. Tim Horan, then in frequent contact with Times editors regarding a business deal, heard talk that Broyard might be fired.

Again and again the history of the feud was laid out in print, except for one crucial detail: exactly what my father had found so offensive about Brossard’s characterization of him. In person, however, Anatole Broyard’s racial background became fodder for speculation once more. In the Village Voice, the columnist Nat Hentoff had included the first line of the French translation of Brossard’s novel, which had been published in the original version: Le bruit courait qu’Henry Porter avait du sang negre. Among my parents’ neighbors in Connecticut, some of whom were Voice subscribers, were people who caught the reference to black blood. Irving Sabo, who lived next door, recalls the article being the topic of conversation for a period.

Could my father really have believed that Brossard would remain silent? The recklessness of his behavior suggests that he was too blinded by his desire for revenge to think through the possible consequences, or else he didn’t feel that he had anything to hide. What’s very clear is his determination to defend his right to be the sole arbiter of his own identity at any cost.

If his new bosses hadn’t heard the rumors about Broyard before, they had now. My father managed to quiet the brouhaha with his assured dismissal of Brossard’s charges in the letters section of the Book Review. However, some of his collegues noted a trickster tendency about the new critic, which they never completely forgot.

The culture editor, Arthur Gelb, who was responsible for actually hiring my father, maintains that he had always known about his racial identity, while Abe Rosenthal, the managing editor at the time, told me a few months before he died that he only learned after my father joined the paper. Years later, both men took the position that it didn’t much matter to them and that they even felt sympathetic to my father’s situation. Gelb remembered discussing it with my dad in relation to a book that Gelb was working on about self-hating Jews, while Rosenthal said that he was delighted to learn about the “addition of his background,” but the idea that my father had to declare himself as white or black was ridiculous. Still, given the climate at the Times, it was easier for my father’s bosses if he let people go on assuming he was white.

Mel Watkins—the first African American editor in the Sunday section, which included the Book Review, Arts and Leisure, and the magazine—explains that it would have been difficult for the higher-ups to acknowledge having hired a black reviewer in the early seventies because of “an abiding assumption in America at the time that blacks were not capable of the kind of objective analysis that was necessary to be a critic.” Watkins, who worked as an editor at the Book Review between 1965 and 1985, had actually been told that by a senior editor at the paper.

During his tenure Watkins made an effort to suggest black reviewers for books by white writers to correct what appeared to him to be a major inequity. “Although no one would think twice about having Norman Mailer review James Baldwin,” he observes, “no one at the Times would have easily accepted the idea of Angela Davis reviewing William Buckley.” But his efforts were rarely successful, which served to perpetuate the belief that black writers could only write about black subjects. Another African American editor at the Book Review, Rosemary Bray, recounts in her memoir, Unafraid of the Dark, how she was turned down for the job of daily book critic in the early 1990s. After looking at her clips, the hiring editor determined that she wasn’t ready yet: too much of her writing was about black people and she needed to expand her range.

During his nineteen years at the Times, that accusation would never be hurled at my dad. From the beginning, African American writers and intellectuals believed that he was particularly hard on black authors. It’s true that he was harshly critical of any writer whom he judged to be sacrificing aesthetic concerns for a political agenda. About Toni Morrison’s otherwise well-regarded fourth novel, he wrote: “Tar Baby may be described as a protest novel, but the reader might have a few protests too,” and then went on to pick apart Morrison’s book. At the same time, Mel Watkins remembers my father defending Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver, leader of the Black Panther Party in the late sixties, because the memoir delivered its message with inimitable style. What’s certain is that my dad didn’t use his platform to promote black literature, a fact that made some African Americans who knew about his ancestry very angry.

Among many readers, however, my father’s high-toned pronouncements earned him a devoted following. The novelist Evelyn Toynton, who later became his student and close friend, recalls discovering my father’s column. “It was so amazing to read anything so literary in a newspaper. I still think it was some of the best literary journalism we’ve ever had in this country.” In his criticism my father was finally able to find the fluidity and confidence that had been evading his fiction. Mel Watkins comments: “What I found fascinating was his ability to take the strict academic or intellectual approach that at the time was presumed to be a part of white culture and combine it with the looseness, vividness, and spontaneity of black culture.” Yet my father still couldn’t synthesize these different aspects of himself in his more personal writing.

After my dad had spent a couple of years on the job as book critic, it became apparent to his publisher that he wasn’t going to finish his novel anytime soon. His editor canceled his contract, and my father had to pay back the advance he’d received fifteen years earlier. But he himself still didn’t give up hope of finishing the book. During his vacation that summer, my father took out the manuscript for the first time in nearly a decade. He started revising the last thing he’d been working on: a chapter about the narrator visiting his newly widowed mother, who has begun to act as if she is dying too, although there’s nothing physically wrong with her. At first the son suspects that she’s trying to shame him into being more attentive, but then he wonders if she’s launched her campaign out of concern for him, as if to say, “Here, feast on me, fill up while you can.”

When my father began this chapter back in the mid-1960s, his mother was as far from death as the mother in the story. But in the intervening years, Edna had suffered a series of small strokes that left her unable to take care of herself. As my father started the new draft, the idea of his mother’s mortality was no longer abstract. Neither was his guilt about their relationship. Except for lending a hand with the arrangements to move her into a nursing home a few years back, he hadn’t seen his mother much since my brother and I were born.

Say, Mom, what’s this all about. You’re not dying.

I want to have time to say goodbye, Paul. You know I never could move fast.

The previous fall Edna, accompanied by Lorraine, had come out to Connecticut to pay her single visit. I had just turned seven and Todd was nine. In my memory I can see an old unfamiliar woman reclining in a lawn chair, with her feet propped up on a pillow. After spending an hour or two sitting in the backyard, we all had an early dinner at the country club next door, and then Lorraine and Edna drove back into the city.

Last suppers. Meals as elaborate as bequests...she drank me in as if she expected never to see me again.

Among my father’s correspondence, I found a note from his mother dated a week or two prior to this visit. Over the years, she’d sent birthday and holiday cards and letters. Always they struck the same note: chatty and nonconfrontational, with a teasing admonishment of her rascally son and a motherly pride underneath. This note was written in shaky penmanship, and Edna had used a Christmas card, although it was late August. It read: “Dear Anatole,...I am [not] that young and gay and would love to see the children for once in my life. Why don’t you bring [them] or come get me for a day. I would love that very much. I am getting 76 in Dec....Love, Mom.”

Her old-person handwriting and the skipping record of her brain, along with the straightforwardness of her appeal, as if she no longer had time for diplomacy, must have scared my father, for Edna came out a week or two later. Afterward another note arrived, this one addressed to my mother, thanking her for the visit. Edna mentions how pleasant the yard had been to sit in, and how adorable Todd and I were. Perhaps, she writes, she can come again before the weather gets too cold.

But there would be no more visits. My mother was drinking heavily at this time, and she suggests that my father wouldn’t want to risk his mother and sister seeing his wife drunk. And by the time my mom was sober, Edna’s health had deteriorated to the point that she couldn’t leave the nursing home anymore. But for Edna that single trip could at least silence any doubts about what her son was doing out there in Connecticut. She could tell anyone who dared to ask (and no one would, except perhaps Shirley or Frank) that Anatole had even taken her and Lorraine to his country club for dinner.

As Shirley points out, being seen in public with her mother or Lorraine wouldn’t have caused a problem for my father; she and Frank, on the other hand, weren’t invited. But Edna wasn’t inclined to dwell on how my father was living his life, as long as she could maintain some kind of relationship with him. “She never raised a question about why you didn’t know that we existed,” Shirley tells me. “It might upset something.”

Over the next few summers, my father kept writing and rewriting the chapter about Edna, each draft slightly different from the last, each one increasingly marked by cross-outs and additions, each mother a little less tangible than the last one. But he never managed to bring the story line to some satisfying conclusion.

If [Nat] resembled his blueprints—a pale diagram of a father—she was like her cooking, palpable. She wasn’t going to “pass away.” She’d spill and splash, flounder and putrefy. She might even make a scene...

In the end Edna simply devolved into vagueness until she no longer recognized her son. And it was my father who made the scene, tearing apart the refrigerator on Mother’s Day. I can still recall the surprise and hurt in his voice when he told me about visiting her at the nursing home. “She didn’t recognize me,” my father had said. “She didn’t even know her own son.” It hadn’t occurred to him that just as a son could forget his mother, so too could she forget him.

I’m dying, too, I’m next....Have you anything to say, Paul, something you’ve forgotten to do? I hope you won’t put if off too long.

A shadow of resentment obscures my recollections of my grandmother during our single meeting. There’d been a quality of formality to the day—my brother and I were made to dress up and sit quietly. I had trouble understanding my grandmother’s strong New Orleans accent. I think, too, I found something vaguely threatening about her presence, as if these strangers who had appeared out of the blue would take my father with them. I’d only ever known him as my dad, and in the blunt logic of my seven-year-old brain, I didn’t understand that he could be a son and brother too.

I imagine that my mistrustfulness made me taciturn and stand-offish with my father’s mother. The few times I’d been around old people—mostly the grandparents of my friends—their frailty, medicinal smells, and incongruous turns of conversation had made me keep my distance. I wonder, did I let Edna hug me? Did I call her grandma? Did she look at me as if to drink me in?

After his mother’s death, my father began to second-guess some of the choices he’d made, often in the Times column he had recently started writing about our life in Connecticut. He wondered if the “excessively sheltered” upbringing that he’d provided for my brother and me might prevent us from developing the necessary toughness or tolerance to survive in the larger world. Also, although he liked the Wasp lifestyle for the security and advantages it promised, he hadn’t necessarily counted on his children becoming Wasps themselves. Was he raising my brother and me to be as innocent and uniform as sheep, lacking any irony or a tragic sense of life? Was he guaranteeing that we would grow up to be dull? He questioned whether his creative energy had become stagnant in this picturesque setting, ensnared by rose vines and ivy into complacency. Perhaps he could have finished his novel if he’d been more anxious, more desperate. A view of skyscrapers, empty lots, and discarded mattresses might have been more conducive to the modern sensibility. Was this life worth everything that he’d forsaken?

In April 1979, six months after my grandmother died, my father recounted in his column how as a young man he’d run away to Greenwich Village, “where no one had been born of a mother and father.” There he and his friends had “buried our families in the common grave of the generation gap.” But now that he was a father himself, he had begun to reconsider his relationship to his parents. “Like every great tradition, my family had to die before I could understand how much I missed them and what they meant to me.” He wondered if my brother and I would ever try to put him behind us. Or did we understand that “after all those years of running away from home, I am still trying to get back?”

A year or so later, my father was waiting for an elevator with Evelyn Toynton in a friend’s apartment building when he mentioned, almost out of the blue, that there was a C on his birth certificate. When she asked him what it meant, he told her it stood for “colored.” Then the elevator doors opened, ending the conversation.

After that my father would occasionally raise the subject with Evelyn, but always when they were about to arrive somewhere or walking back from lunch and there wasn’t time for much discussion. He told Evelyn about his father sitting the family down in the living room and telling them they had to be white. Another time he mentioned that he’d been beaten up by the darker-skinned kids in the neighborhood. Evelyn recalls: “He stopped walking and said, ‘You don’t know what it was like. It was horrible.’”

Looking back now, Evelyn thinks that my father may have been probing to see how people would respond to the revelation of his background. “And it almost felt like, when he realized that people wouldn’t care—certainly people like me didn’t care—that it was weird for him,” Evelyn says. “Because if nobody would care, then why had he done it?”

It was around this time, the early 1980s, that my father toyed with the idea of going public about his racial identity. One evening he visited Harold Brodkey and his wife, Ellen Schwamm, at their apartment in Manhattan for help with his novel. After listening to him read from various sections, they gave him the same feedback he’d been hearing for years from other friends and editors: the writing was too controlled and distant; he needed to let go to get back to the immediacy of his earlier fiction. Harold told him that it seemed like he wasn’t being honest, and if you evaded the truth, this was what you got. My father wondered out loud if he should try to write about being black.

Harold and Ellen had heard the rumors, but they’d never discussed my father’s racial identity with him before. Ellen, who is also a novelist, thought that writing about it was a wonderful idea. She suggested that such a book would free him. But Harold said that he didn’t believe that my father had lived it. That he was really black wasn’t the truth either. If my father had felt himself to be actively passing as white, Harold surmised, there would have been more of a gulf between my dad and my brother, my mother, and me, that the act of keeping a secret would have made my father seem more different.

Harold and Ellen asked him why he needed to be secretive about his background in the first place—almost everyone seemed to know already, and wasn’t it just one black relative somewhere in his past anyway? My dad told them that in fact both of his parents were black. He said that he had never had anything in common with his family; they didn’t understand him. When he started Brooklyn College at age sixteen, he’d felt more at home among the Jewish students. Sometimes it seemed to him that he’d been born into his family by mistake.

When I talked to Harold and Ellen in 1994, Harold described my father wearing a “shit-eating grin” when he talked about being black. “He said how well a book like that would sell,” Harold recalled. “How he could make a lot of money.” My father’s writer’s block wasn’t only frustrating creatively; my brother and I were about to start college, and my dad needed a book advance to help pay for our tuitions. Harold also thought that my father told him because he knew that Harold would out him one day and then he would be forced to explain himself. But my father died before Brodkey got around to exposing him, and then Harold was diagnosed with AIDS and busy finishing up his own life.

My father eventually told Brodkey that he didn’t want to write about being black because he simply didn’t want to be viewed as a black writer. Also, he didn’t want Todd and me to be seen differently. Harold kept encouraging him to tell us about his background, but my father always refused, insisting that it had nothing to do with us. We were white.

My mother had also begun pressing my father about the need to tell the children. She felt that we had a right to know, both for ourselves and for the sake of our own children. But my father would immediately grow angry whenever she brought up the subject. To end the conversation, he would agree to tell us one day, but we didn’t need to know yet.

When was the right time, though? When we were so secure in our white identities that the revelation wouldn’t change our conception of ourselves? When the world no longer made distinctions between black and white? When we stumbled on the secret by accident? If he’d ever actually tried to imagine our reactions, he might have been scared. Perhaps he’d done such a good job raising us as white that we’d be upset or angry. Maybe the wall he’d erected between our lives and the colored world of his childhood would prove so high that we’d lose sight of him across the divide.

Equally troubling might be the possibility that we’d embrace our father’s background. To his mind, if we started to identify as black, then all the advantages he had worked so hard to provide us—and everything he’d sacrificed along the way—could prove for naught. Through the force of his personality, my father had managed to thwart any racial stereotypes’ being “pinned” on him by people who knew about his identity, but he couldn’t be certain that we’d have the same sureness of character to deflect the distorting influence of prejudice.

My father might have wondered how springing this news on us would be any different from what his father had done to him as a kid. He knew firsthand how confusing it could be to grow up thinking of yourself as one thing only to be told you’re another. His father had also been trying to make a better life for his family, but he’d hijacked his children’s sense of themselves in the process. My aunt Lorraine suggested to my mother that she’d never married because of the mixed messages she received as a child about her racial identity. Could my father expect us to keep his secret for him? Would forcing us into becoming his coconspirators be any better than withholding the truth?

My father could have come up with a million excuses about why he shouldn’t tell us. Perhaps the simplest explanation is that he was afraid we’d be disappointed in him. He might have gone on postponing forever, but then he got sick and his time ran out.

In a talk about having a critical illness that my father gave at the University of Chicago Medical School six months before his death, he mentioned the need to develop a style for finishing up one’s life. He’d always viewed a person’s style as the literal embodiment of his personality. For him style extended far beyond fashion to include how a person moved, the language he used to express himself, the angle of his observations. In his view we could deliberately cultivate these aspects of our character by paying very close attention to our instinctual likes and dislikes, our innate prejudices when responding to the world. As if we were each uniquely made instruments, our job in life was to continually tune ourselves, tightening this and loosening that until we hit upon our most natural, most authentic sound. My dad often spoke of life as a rhythmic process—“When I was happy, my rhythms, my tuning were good...and when I was unhappy, I didn’t have any rhythm at all.” Finding his unique sound allowed him to dance.

In finishing up his life, my father adopted a style that defied and disparaged his illness. When his oncologist suggested that the most effective remedy for prostate cancer was an orchiectomy—removal of the testicles—my father told him that losing his balls might depress him, and that depression could kill him quicker than cancer. He entertained us with stories about his hospital roommate, a thug who’d broken his jaw during a bar fight. After having a catheter removed, my father couldn’t make it to the bathroom in time and peed all over the floor, and this man, who had drawn blood in anger, leaped onto his bed and began dousing the room in air freshener.

Just as my father had counted on his style to protect him from the diminishment of self that came from being black in the 1930s, he expected it to safeguard him against the diminishment of self that accompanied having a fatal illness. Rather than wasting away, he would become a crystallized version of Anatole, more insistently himself than ever before. As cancer disfigured his body and disoriented his mind, this tactic would keep him in love with himself, which was crucial to maintaining his will to live. And it would also allow his family and his friends to continue loving him as he became more and more unrecognizable.

If my father told my brother and me about his racial background, how could he have remained himself while also revealing that he wasn’t who he seemed to be? Even if he convinced us that his few drops of black blood didn’t mean that he was black, would we nonetheless feel alienated by the drops of secrecy and conclude that he’d become a stranger?

In the final months of his life, my father agreed to see a family therapist with my mother. They’d been fighting a lot because my father wouldn’t go along with the macrobiotic diets and vitamin cures that my mother wanted to try now that they’d exhausted the treatments available through Western medicine. In the session, my father tried to explain to my mother that he was in too much physical pain to tolerate the taxing side effects of these alternative cures. When the therapist asked him about other moments of pain in his life that went unrecognized, my father began talking about his childhood and broke down sobbing. He described feeling caught between two worlds, and how much he blamed blacks for acting in a way that invited prejudice. He talked about being beaten up because of his white looks and black identity, and how his parents had pretended not to notice. And he railed against his father, dead now for forty years, for protecting him neither from those bullies nor from the turmoil of growing up in this racial limbo.

In three decades of marriage, my mother had never heard her husband talk about his childhood or internal strife about his racial identity with such honesty or anguish. She was deeply saddened to learn that he’d been carrying around this burden by himself for all this time. Both she and the therapist suggested that sharing this pain with the people who loved him could ease his suffering. Telling my brother and me would not only help us to understand him better, but it might make my father feel less alone at the end of his life.

I remember visiting my parents at their house after that therapy session. My father took up what had become his constant position in recent weeks—reclined on his side on the couch in the living room. But as he lay there, with his head propped in his hand, he held forth with such enthusiasm that I could almost view him as simply relaxing. He spoke optimistically about the efficacy of the alternative treatments and how he would give them another try. He mentioned writing projects that he was eager to finish and all the work that he could still get done. And he raved about this magician of a therapist who had accomplished in a single session what forty years of analysis had not. “I feel as if I’ve been completely recalibrated,” he said to me, without explaining what he meant. “Like a brand-new man.” In the therapist’s office, my father had glimpsed a way to reveal himself without betraying who he was or changing the way that his children saw him.

But in Martha’s Vineyard with Todd and me a few weeks later, the right words failed to come. In my father’s dream about being on trial for an unspecified crime, he’d made a speech in his defense that was so moving that even in his sleep he could feel himself tingling with it. The style in which he’d lived his life was a conviction he felt in his bones. But even though my brother and I were made from those same bones and blood and flesh, he couldn’t be sure that we’d share his feeling about the rightness of what he’d done. As he grew more sick, the frailty of his spirit couldn’t tolerate anything short of transcendence.

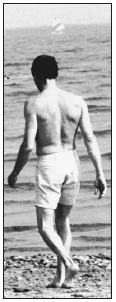

A few months before my father died, my friend Chinita and her boyfriend Mike paid another visit to my family’s house on Martha’s Vineyard. One early evening we all headed down to some nearby tennis courts. None of the three courts were occupied, and we spread across them, volleying back and forth. My father started out hitting with us, but he was too weak to play, and after a minute he said that he’d rather watch. Mike and my brother began a game, and my dad took a seat, leaning up against the wire fencing beside them.

Two courts away, Chinita and I had been playing for a half hour or so when the exhortations of my father caught our attention. We stopped to see what the commotion was about. Mike and Todd were both good athletes who could have been great tennis players if they’d ever put their minds to it, but Mike became a competitive rower while Todd took up running. Now Chinita and I watched Mike sprint to the net, scoop up a drop shot, and send it in a lob over Todd’s head, and Todd turn and race to the baseline, leaping to slam it back with a high backhand. The rally continued on like this, with neither of them able to make a bad shot and my dad exclaiming after each one: “Keep your eye on the ball!” and “Don’t think!” and then just calling out their names or hoots and cries of admiration.

The light started to fade but the match went on, and still they kept making improbable shot after impossible get. Chinita and I abandoned our game and sat down to watch on the other side of the court, adding our shouts of praise to the mix. Neither Todd nor Mike had played as well before, but they didn’t seem to be trying to win, because that would mean the end of this match and the spell that had come over them, and the end of the astonishment of Anatole, without which they would never play as well again.

I remember glancing over at my father, who sat with his knees tucked into his chest and his arms wrapped around his legs, the only movement his head tracking the ball back and forth across the court. He looked completely enthralled, as if he had a front-row seat for the finals of the U.S. Open. And he seemed so happy to be celebrating this evidence of vitality, strength, and panache in the world. How graceful life could be! How extraordinary were human beings! No matter the shadows stretching across the court, we could all live on through the immortal magic of this evening.

A few nights later, my father celebrated his seventieth birthday. His illness had reached a stage where it was apparent to everyone present that he wouldn’t live to see seventy-one. Michael Vincent Miller came down from Boston to join a collection of my father’s closest male friends from Martha’s Vineyard. Before dinner everyone sat upstairs in the living room, drinking wine and eating hors d’oeuvres. My father had been feeling nauseous and weak all day, but he insisted that my mother go ahead with the party. After chatting for a while, he announced that he was going to lie down in his bedroom but he wanted everyone to continue celebrating without him. His friends started protesting that he could lie on the couch, that he should try to eat something, that maybe they better leave so he could rest in peace, but my father silenced them with a raised hand as he paused in the doorway of the bedroom.

Never has a man been so rich in friendship, he began. He went around the room, describing the particular talents of each man there: this one’s ability to fix anything and find his way to anywhere; that one’s skill at deciphering the most mysterious human behaviors; another’s sophistication after living in a dozen different countries; someone else’s mix of subtle humor and exalted conversation. He talked about each friend at length, making sure that they knew that their best selves had been seen and appreciated. The men didn’t say anything in response, but I watched each of them nod slightly or sit up taller in his seat, as if to acknowledge acceptance of my father’s pact. They would carry on being their best selves in his absence, with even more wit and animation than before, and they would look past the hollow-cheeked figure who needed to lie down and recognize my father’s best self too.

Someone raised his glass and said, “To Anatole.”

“To Anatole!” came the answer.

My dad raised his eyebrows and smiled. Then he shut the door and didn’t come out for the rest of the night.