During a visit with my aunt Shirley in the late winter of 2002, I raised the subject of disposing of her parents’ ashes. They represented one piece of my father’s unfinished business that I felt I could put to rest. For a while I’d been looking for the right moment to tell her that they were still sitting in their boxes in a closet in our house. Shirley had been telling me how at the end of my grandmother Edna’s life, my father hadn’t been involved in her care other than arranging for her funeral. Since all of their mother’s friends were dead, there was no service, just a private cremation.

“Actually, the ashes, we still have them,” I said. “And your father’s too. My dad never did anything with them.”

Shirley made an annoyed face.

“I know,” I said, shaking my head. “I was thinking that perhaps you might want them back. Since they were your parents, and you had a relationship with them...”

“Well, what am I supposed to do with them?” Shirley asked.

“Do you have a family plot or somewhere you could bury them?”

She shook her head. “There’s no room.” Shirley explained that the vault where the ashes of her husband and Lorraine were stored had a limited number of spaces and they were all spoken for.

I could see that she resented having the responsibility of yet another thing her brother had neglected thrust upon her. We sat there in an awkward silence. Finally she asked, “What do you think your father intended to do with them?”

“I don’t know for sure,” I said. I told her about a chapter that my dad had written for his novel in which his character headed to the Brooklyn Bridge to scatter his father’s ashes and then changed his mind just as he was about to toss them into the East River. I shrugged and said, “So maybe he couldn’t bring himself to part with them.”

“Then why don’t you bury them next to him,” she suggested.

My heart beat a little faster. I said, “I think that would be really nice.” I told Shirley about an idea I’d been entertaining—that she and Frank and Denise and the kids could all come up to Martha’s Vineyard, and we could hold some kind of ceremony to bury the ashes. “Since our two families have never gotten together, it would give us a chance to talk,” I said. “It could be healing.”

Shirley nodded; she seemed to like the idea. I offered to call Frank and extend the invitation to him as well.

After leaving Shirley’s house, I headed for the subway on Central Park West, but when I reached the avenue, I decided to walk through the park instead. It was the middle of the day during the middle of the week, and the park was nearly empty. The air held the damp clinging cold of late winter, but with my hat pulled over my ears, my scarf wound around my neck, and my fantasies about this weekend on Martha’s Vineyard, I felt snug and warm.

I pictured us in the living room after dinner. Shirley is talking about her father—how he used to wear his pants high under his chest (he thought he had unusually long legs), which would draw sarcastic remarks from her mother. Frank recalls his grandmother’s dating advice when he was in high school, and her prediction when Denise came along that she was the one. Todd and I share the little we know from our father’s stories, delighted each time Shirley corroborates a detail. But mostly we listen. Maybe Frank’s kids are hearing some of these stories for the first time too.

The conversation moves on to the family’s racial identity. Shirley describes the confusing climate of her childhood and her own process of becoming politicized about civil rights. Frank mentions all the gains for blacks that his parents helped to secure, and Denise talks about their efforts to instill in their children a sense of pride in being African American. They all share how my father’s rejection of their family hurt them. Perhaps my mother tries to explain my father’s decision from his perspective, and while Shirley and her family don’t offer their forgiveness, there is a sense of satisfaction that comes from everyone having their say. My brother and I emphasize that we hope to be in their lives now, that we would like to be a family moving forward together.

I had walked seven or eight blocks, lost in my thoughts. Near the Eighty-first Street entrance to the park, I came upon some massive outcroppings that called to mind the boulders pocking our yard in Martha’s Vineyard. We’d moved a smaller one to the cemetery down the road to mark my father’s grave site. I paused to lean up against the rock face and looked up at the gray sky. I thought how my mother’s potter friend could make urns for Nat’s and Edna’s ashes—as she’d done for my father’s ashes a decade before—and that hundreds of years from now, the clay of the different urns would break down and the ashes would migrate through the dirt to mingle together. I thought how I could bring my own children to the grave site and tell them the complicated story about their grandpa Anatole and his ancestors and the wide-reaching effect of racism. But there would be a happy ending, because here were his parents: my father’s family belonged to us too.

The stone grew cold against my back, pulling me from my reverie. I never went to my father’s grave now—the public nature of its setting and the orchestrated tenor of the visit usually made me too self-conscious to feel any connection to my dad. As I straightened up and headed for the subway, walking briskly, I shook my head as if to clear it. Perhaps my fantasy about what this weekend might accomplish was a little far-fetched, but still, spending time with Shirley and Frank could bring some welcome closure.

Throughout the spring I called Shirley every month or so to try to arrange the visit. Frank had agreed to the idea as well, but the uncertainty of his kids’ camp schedules and various vacation plans kept preventing us from setting a date. Then one day, while I was at the New York Public Library, my cell phone rang. It was my aunt calling to say that she and Frank had changed their minds.

I had been working in the Allen Room, a workspace on the second floor available to authors. I stepped into the hallway to take the call, and stared out the window at the buses gliding down Forty-second Street as Shirley broke the news.

“This may come as a surprise to you, but we want to bury the ashes in New York,” she said. “Frank and I had a long conversation. He was very close to his grandmother, and we think that makes sense. They were New Yorkers, after all. They belong here.” But she stressed that the decision wasn’t final and that I should talk it over with my mother.

“But I thought that you didn’t have room for them,” I said.

“Well, we do.”

“But you agreed they should be buried next to my father since he couldn’t part with them.”

Shirley laughed a little bitterly and said: “I don’t think it was the case that he couldn’t part with them.” She explained that she had always felt uneasy about burying her parents on Martha’s Vineyard, only she hadn’t realized it until she talked to Frank.

“So I guess this means that you don’t want to come visit,” I said.

“It’s not that we don’t want to come. It’s just that there’s no point if we aren’t going to bury the ashes there.”

Outside, the streetlights started to sparkle and blur.

“But,” Shirley continued, “you should talk it over with your mother, and then we can discuss it again.”

I mumbled an answer, not trusting my voice to speak. We hung up and I lowered my head and began to cry as hard as if I’d just learned that a beloved grandparent had died. I turned from the window, and the library’s grand white marble hallway stretched before me.

Even then I knew Shirley was right. Her parents’ ashes didn’t belong on Martha’s Vineyard. They hadn’t been welcomed there when they were alive, and my father hadn’t earned being reunited with them in death. Frank had actually been a part of his grandmother’s life. His kids, not mine, deserved to visit wherever Edna ended up and hear stories about their ancestors. But I couldn’t get past my sadness over having to give up the one connection to my father’s parents I had.

The next time my mother came to New York, she brought the boxes of Nat’s and Edna’s ashes with her. I’d made a plan with Shirley to drop them at her apartment, and then the three of us would have brunch in the neighborhood. After my mother and I parked, she retrieved the vinyl shopping bag containing the ashes from the backseat. I tried to take it from her—it was heavy and we had three or four blocks to walk—but my mother insisted on performing this ritual herself.

On the way to Shirley’s, we talked about the other ashes that my mother had transported in her life: her mother’s from Norway to New York and my father’s from Cambridge to Martha’s Vineyard. In her midsixties, my mother still performed modern dance and did the chainsawing and brush cutting on her property. She carried her burden with her shoulders squared and her back straight. I realized that I had no idea where her parents were buried; I’d never asked.

After handing over the ashes, we headed for brunch. My mother and her sister-in-law hadn’t seen each other since my father’s memorial service twelve years earlier—the only other time they’d met—yet the conversation never flagged during the meal. We discussed opera, the current Bush administration, how much the Upper West Side had changed, with my mother and Shirley nodding continually in agreement.

When my mom got up to use the bathroom, I seized the chance to tell Shirley that I was hoping to be included if she and Frank were going to have a ceremony. She shook her head, and I wasn’t sure that she understood what I was asking.

“It would mean a lot to me if I could participate in disposing of the ashes,” I said, my voice low and urgent. “I just really want to be a part of this family.”

Shirley gave me a sad, curious smile. “But you didn’t know them, Bliss,” she said gently. She gestured at an envelope of photos of my brother’s new twin daughters that my mother had brought along. “And you have a big family of your own.” Well, not exactly.

My mother returned to the table and sat down. I was quiet while we paid the bill. We accompanied Shirley to her corner on the way back to the car. Just before we parted, she clasped her hands to her chest and said: “I can’t wait to call Frank and tell him we have the ashes back!”

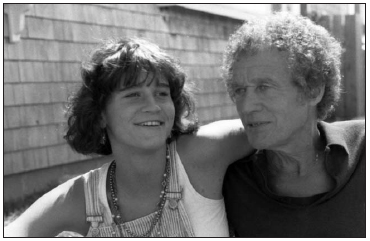

I’ve continued to visit Shirley or talk to her on the phone a couple of times a year. Her warmth toward me always takes me slightly by surprise. When I tell her that my boyfriend and I are thinking about having a baby, she exclaims excitedly about having another grandchild. “Grandniece or nephew,” I correct her, smiling broadly. She answers my endless questions about her parents and her childhood and digs through files in her basement for family photos and birth certificates to help me in my research. “When are you going to finish that book?” she pesters. “I can’t wait to read it.” And despite my father’s rejection of her, she often comes to his defense, alerting me to some favorable mention of him in the press and commiserating when he has been portrayed badly or unfairly.

Yet while Shirley knows that I don’t have any other close relatives nearby, I have never been invited over for Christmas or Thanksgiving or even a Sunday dinner. She tells me news of Frank’s kids—how they’re faring at college, whom they’re dating, what they’re doing for the summer—but she doesn’t encourage me to see them. Whenever I suggest all of us getting together, she makes an excuse about Frank’s and Denise’s busy schedules. My efforts to make plans myself with my cousin and his family were always greeted enthusiastically, but somehow the follow-up call to arrange the logistics would never come. Eventually I just stopped trying.

Talking with my mother in her car after brunch that day, it occurred to me for the first time that my father’s family might not want me in their lives. My mother suggested that Shirley and Frank could be unconsciously keeping their distance to protect me from their anger.

“But it wasn’t my choice not to see them growing up,” I said. “And it’s not fair to hold what Daddy did against me.”

“It wasn’t Shirley and her kids’ choice either,” my mother reminded me. She suggested that I had to respect their wishes, just as they had respected my father’s wishes for all those years by never showing up on our doorstep.

“But wouldn’t coming together as a family now be a way to get over this?” I said. “Wouldn’t it be better to try to put this pain behind us?”

My mother put the key in the ignition and turned over the motor. She looked at me and said, “Some wounds can’t be mended.”

The extended Broyard clan has shown more interest in connecting with their estranged relatives. For these second and third cousins, my father was just one of a number of aunts, uncles, and cousins who’d become lost to the family after crossing over the color line. His rejection of them wasn’t viewed as anything personal. In June of 2001, my mother, my brother, his wife, and I attended a family reunion in New Orleans that I’d helped my cousin Gloria to organize. There I encountered many relatives who sought the kind of reconciliation that I’d been hoping to achieve with Shirley and her family.

Gloria had contacted me after reading about my father in the New Yorker. She’d also recently discovered her African ancestry, and she was eager to meet the family members whom her grandparents had cut off after moving out west to live as white. I mentioned the idea of a large-scale reunion that some of the California cousins and I had been tossing around, and Gloria took the initiative of coordinating it. After two years of planning and hundreds of letters, phone calls, and e-mails, ninety-seven Broyards assembled in a historic, old-world-style hotel in downtown New Orleans.

People came from around New Orleans and across Louisiana; from Massachusetts, California, Georgia, New York, Arizona, and Utah; from as far away as Hawaii and Germany. Raised as African American, Creole, or white, some had pale skin and blue eyes, others were dark with brown eyes and black hair, then every shade in between. Later many people admitted that they’d been hesitant to attend the reunion because they didn’t know which side—the white or black one—was throwing it. For three brothers from Florida, the weekend was confirmation of what one of them had already suspected—their mother wasn’t part Mexican as she used to say to explain their dark skin tone.

The first night, we gathered for a cocktail party in a small banquet room. The family tree, dating back to Etienne Broyard’s arrival in 1753, covered the tables lining the walls. Everyone leaned over the sheets of paper, looking for their own name, tracing the crooked branches until they found another name they recognized. Sometimes their paths crossed with the person beside them, and they straightened up, extended a hand or opened their arms, and said, “Looks like we’re related.”

When I explained how I fit into the family, people nodded and said, “So you’re Anatole’s daughter.” Even before his story became public knowledge, many of my relatives knew about the Broyard who wrote for the New York Times and was living in Connecticut as white with his family. No one openly criticized his choice, and many were quick to point out that they didn’t judge him, citing the lack of opportunities facing blacks at the time and “your father’s understandable desire to better the lives of your family.” But there were also stories like the one told by my cousin Janis, who was raised as black in Los Angeles among my other California cousins.

When Janis was growing up, her uncle Emile once came over to her house with clippings of cousin Anatole’s writings. When Janis asked if she could meet my dad, she was told that she must never contact my family, because we were living as white and we didn’t want to know her. “It made me think there was something about myself that I should be ashamed of,” she said. As an adult, Janis understood the economic rationale for passing. Yet whenever she came across any Broyards in the phone book or on the Internet and thought about getting in touch, that admonition repeated in her head: They don’t want to know you.

I told Janis in a quiet voice that I would have liked to know her if I’d just been given the chance. I hoped that my yearning now to be part of this family could make a small amends for what my father had done.

Unlike some families, for whom seeing each other feels more like a duty than a pleasure, the attendees at the reunion couldn’t wait to get together again. For so many of us, even those who stayed on the black side, the color line had come between people in some way, and we were eager to get past it. The New Orleans Broyards began having lunch once a month. When I was in town, I would meet up with them too. The clan in California began to include more of the extended family at their gatherings. The handful of us in New York got together as a group or one-on-one on occasion. And Gloria kept us posted on the milestones in people’s lives with a family newsletter. Everyone clamored for another reunion. The natural choice would have been 2006—five years after the first one—but then Hurricane Katrina devastated the city that had been home to generations of Broyards and scattered many family members across the country.

The majority of my New Orleans relatives’ homes were located in the flooded neighborhoods. My cousin Sheila, who started me on my family research, her aunts Nancy and Jane, and her grandmother Rose managed to leave in time, but all of their houses were destroyed. The nursing home where my outspoken cousin Jeanne had moved because of her worsening asthma had no provisions to evacuate its residents. She arranged a ride to the Superdome herself and then spent three days and nights praying that the emergency generator would continue to power her respirator. Eventually Jeanne was airlifted to a hospital in Baton Rouge, where a nurse contacted me after spotting my inquiry on a Red Cross list.

In the weeks following the hurricane, a network of cousins and I managed to locate all the New Orleans Broyards who had attended the reunion to ensure they were safe. More than a year later, however, I’d lost track of many people’s whereabouts. Some were headed to Austin and Houston; others planned on settling in Baton Rouge or Lafayette; still others spoke of going to Atlanta. I only know of two family members who returned to New Orleans. One of them, my father’s second cousin, O’Neil Broyard, was the proprietor of the Saturn Bar, an infamous dive in the lower Ninth Ward that was popular with locals and visiting celebrities for the surrealistic murals that covered every inch of its walls and ceiling. After being forcibly evacuated to St. Louis by state troopers, O’Neil came back to reopen his bar and then died of heart failure in the midst of cleaning it up.

The city’s black middle class, to which the majority of my family members belonged, has mostly disappeared. Thousands of city employees and schoolteachers—the bulk of whom were black—were laid off, which meant that the black lawyers, doctors, dentists, and businesses that served them lost their clientele. Despite the celebration by the national press of the first post-Katrina Mardi Gras, my friend Keith Medley, whose guesthouse was spared by the hurricane, pointed out the absence of black Carnival balls compared to twenty or thirty in the past.

The uncertain future of New Orleans East—where many family members and other middle-class blacks lived—makes deciding whether to return particularly difficult. In large areas city planners are waiting to see who comes back before committing to providing basic services such as working sewers or police patrols. Those who decide to rebuild anyway risk having their houses demolished if their neighborhoods don’t attract a critical mass of residents. These sections would then be turned into “green spaces” that would provide flood drainage for the rest of the city. Better schools, more job opportunities, and less crime in the evacuees’ newly adopted hometowns give them other reasons to stay away.

The demise of these black middle-class neighborhoods threatens the future of what remained of Creole culture in New Orleans. The community’s previous diaspora, in the beginning of the twentieth century, spawned Creole outposts in Chicago, Houston, and especially Los Angeles. But the circumstances of Katrina not only made it hard for members of the community to relocate near each other, it destroyed their cultural touchstone in New Orleans too. Louisiana-based Creole genealogical groups such as the Creole Heritage, Education, and Research Society (CHERS) and the Louisiana Creole Research Association, Inc. (LA Creole), along with organizations such as the Louisiana Creole Heritage Center based at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana, are working to preserve the culture, but the state grant-making institutions and local residents they rely on for funding and support are struggling too.

The situation of the displaced Creoles brings to mind my grandfather’s departure from New Orleans eighty years earlier. I wonder whether some of the evacuees will also turn into silent figures, pre-occupied by a vanquished existence that survives only in their imaginings.

For me the Creole culture of New Orleans provided the backstory for my father’s relationship to his racial identity. It explained why the label of black or African American was an uncomfortable fit for him, and it expanded my understanding of the black American experience outside the narrative of Middle Passage, slavery, and sharecropping. The constant shuffling of the Creoles of color between the categories of mixed, black, and white made it hard to believe in the legitimacy of any racial labels. It was in New Orleans that I finally understood the dilemma that history had created for my father.

Of course he never acknowledged being plagued by any dilemma; he clung to the belief that his actions were governed exclusively by choice. My father told himself, and me, that he didn’t see his family because he had nothing in common with them, that sharing blood with people didn’t obligate you to them. However, the other relationships in my father’s life suggest that he didn’t actually feel this way. Over the years, he often voiced his disdain for drunks, yet he stuck by my mother through the worst years of her alcoholism. After bemoaning my decision to attend the University of Vermont—rather than the type of prestigious Ivy League school that he expected for his progeny—he came to praise the school’s “quintessential New England college experience.” Todd’s fascination with home security alarms was as incomprehensible to our father as his own love of literature had been to his father; nevertheless my dad applauded the zeal with which my brother applied himself to his chosen career.

None of these are heroic gestures. All parents must reconcile their fantasies for their children with the choices their kids actually make. But I believe that my father was able to put aside his disappointments because he loved us; and that he loved us because we were his family; and that family mattered to him because he’d loved his parents and siblings too. Still, he left them, which perhaps explains why he seemed so determined to prevent us from ever leaving him.

When I was in high school, he proposed turning part of the second floor of our house into an in-law apartment and building a garage with another apartment above it. That way, he told Todd and me, we could save money on rent while starting out our careers. And then when we got married and had children, he went on, he and my mother would be on hand for babysitting. He’d catalog all the advantages to having some grandparents around. Dad, I’d groan. Don’t you want us to have our own lives?

My father couldn’t argue with a desire to make one’s own way in the world. But to his mind, the life that he’d provided for us hadn’t contained any disadvantages. He didn’t recognize how his very overprotectiveness might give us a reason to want to get away. Of course his parents had also been trying to do their best for their children, and that they “failed” by being identified as Negroes hadn’t exactly been their fault.

My husband, Nico Israel, and I are about to become parents ourselves, and I’ve begun to appreciate the complexity and responsibility of legacy. What values and traditions will we pass down? And what accidental flotsam from our pasts will float down unconsciously? Will our child have dark hair and dark skin like some of our ancestors? If our son or daughter asks, What am I? how will we answer? Daddy is a Sephardic Jew with roots in Spain, Greece, and Turkey, and Mommy is Norwegian, French, black, and Choctaw Indian? Will our child’s birth certificate, school applications, and all the other bureaucratic forms encountered during life allow for the record of this complicated history? Since 2000, people have been able to check more than one box under the race question on the federal census, but many states are still following the single-box approach on school forms. What parts, if any, of this ancestral inheritance will our child want to mark down? And will these questions of origin even matter in the future?

From my own father, I inherited a legacy that connected me to the worst and best American traditions: from the racial oppression spawned by slavery to the opportunities created through becoming self-made. Recognizing my forebears’ place in the continuum of history has made me appreciate my own responsibilities as a citizen—of my community, my country, and the world—in a way that simply paying my taxes or casting a vote never did.

As T. S. Eliot put it in his poem “Little Gidding”: “We shall not cease from exploration/And the end of our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place for the first time.” I began this journey with the revelation of my father’s racial ancestry. After sixteen years of exploration—and being by turns impressed and dismayed by my father and his choices—I feel I have only now, with a child of my own on the way, begun to know the dilemma for myself.

I may never be able to answer the question What am I? yet the fault lies not in me but with the question itself. And with that realization, that letting go, I can finally say good-bye.

Every year on the anniversary of my father’s death, I have made a ritual of playing audiotapes of his voice. In none of the tapes I have is he speaking directly to me: one is a lecture he gave on Martha’s Vineyard about his frustration with the way Americans talk to each other; another is the address he gave at the University of Chicago Medical School about what he wanted in a doctor. But the way he offered his elaborate metaphors in a slow satisfied growl or his habit of stalling as he poked fun at himself, then exploded into a hoot of laughter recall his presence more vividly than any photograph or piece of his writing.

The one tape I could never bring myself to play after my father died was recorded at the funeral of Milton Klonsky, my father’s best friend from Brooklyn College. The only other time I listened to it I was fifteen. After overhearing my mother on the phone tell someone that my dad, in the middle of eulogizing Milton, had broken down, I noticed one day a tape labeled with Milton’s name lying on the desk in my father’s study.

I’d seen my dad lose his temper lots of times, and I saw the aftermath of his losing control that Mother’s Day after my grandmother Edna died. Sometimes he’d hinted at a deep sadness in his life before our family came along, and I sensed that he was plagued by vague unspoken regrets, but I’d never seen—or heard—him cry. And I’d thought that hearing such unrestrained emotion would reveal something essential about my father’s character that had been withheld from me so far.

This year, on October 11, the anniversary of his death, I retrieve the tape of Milton’s funeral from the shoe box where I keep my mementos of my father. I place it into a boombox and fast-forward until I come upon my father’s turn to speak, just as I did twenty-four years ago when I first stumbled across the tape. I listen to my dad recount visiting Milton in the hospital. A stroke had left him unable to speak except for a few words. Milton said to my dad, “Do what you have to do,” and then blurted out the word “debauchery.” My father describes trying to make sense of his friend’s enigmatic message. Of all people, Milton understood the bargain that my dad had made: he had introduced him to the literary life that my father eventually chose over his family.

In his typical crowd-pleasing fashion, my father’s portrait of his friend comes out sounding effortlessly artful; he pauses on certain particularly nice turns of phrase that capture the extraordinary qualities of his most luminous companion. And then he pauses for a longer moment, and the next phrase comes out sounding less certain, and his voice cracks as he tries again to speak.

I remember back to when I was fifteen, standing there guiltily in my father’s study, waiting to hear the sound of his tears. I’d been afraid that they might sound grotesque, after being twisted and stored up for so long, like some strange parasite that had taken root in his body years before. And then I remember the anguish I’d felt as the tape rolled on and I glimpsed the boundary beyond which my father would always remain opaque.

Seated at my desk in front of the tape player now, I find this idea less terrifying than strangely consoling. I listen for the moment when my father’s voice breaks off, followed by a distant muffled rustling in the background, the interminable whirring of the tape heads—louder and louder—and then the sound, brump-click, that signaled a button being depressed. Stop. Silence.