Chapter 3

Cryptocurrencies Take Off

At first, many people were attracted to Bitcoin for one reason: anonymity. In February 2011, the Silk Road Dark Web opened. It offered various illegal goods and services, including drugs, stolen identities and passwords, weapons, and sex trafficking. It accepted payment in Bitcoin only. At that time, one Bitcoin was worth about thirty cents. Critics dismissed Bitcoin as the currency of choice for criminals and terrorists, but some investors noticed that Bitcoin’s premise was holding true. It allowed strangers—even criminals—to establish trust and conduct transactions. In short, Bitcoin was working the way its creators intended.

This attracted attention, especially as Bitcoin’s price began a series of dramatic rises and falls. For speculators, Bitcoin appeared to be an opportunity to make a lot of money fast. Law enforcement also began investigations. In the spring of 2013, the US government took down the Silk Road Dark Web bazaar and confiscated more than 150,000 Bitcoins.

Bitcoin, and cryptocurrencies in general, preoccupied government regulators. Regulators are charged with enforcing government rules, especially in finance. At the time, other tech-based services such as Airbnb and Uber were causing a huge disruption in the taxi and hotel industries. Taxi services and hotel companies were forced to compete with drivers and apartment owners who, through the internet, could connect directly with customers.

Regulators wondered if this could also happen to finance. At conferences, they asked nervous questions. Are cryptocurrencies a fraud? What impact could they have on financial institutions? Could cryptocurrencies break the government monopoly on money? US authorities seized cryptocurrency accounts that had traded without being properly registered with federal agencies. China also cracked down, declaring that no financial institution could use cryptocurrencies (although citizens still could). The price of Bitcoin rose and fell with these announcements, but the general trend was higher. At the start of 2014, the value of Bitcoin shot up from about $13 to $770 per coin.

Bitcoin stories now appeared regularly on news shows and in headlines. Bitcoin holders, who had once swapped them for pennies and begged anyone to notice them, were making fortunes. Bitcoin had arrived.

All around the world, cryptocurrencies attracted those who saw a chance to make a fast fortune. South Korea became the third-largest market in cryptocurrency, after the United States and Japan. Poor, young Koreans called themselves dirty spoons. The name was based on the contrast between them and the elite who were said to have silver and gold spoons because of their jobs, wealth, and opportunity. To the dirty spoons, cryptocurrencies seemed a chance to make good money and potentially upend a social order that seemed stifling. They could buy cryptocurrencies even when they had no chance to buy stocks or get a loan to fund a business.

One dirty spoon, twenty-nine-year-old Remy Kim, hosted social media channels on cryptocurrencies. He first learned about them when a hacker took over his hard drive and demanded ransom in Bitcoin. Kim came up with the 1.2 Bitcoins (then worth about $800), but he grew fascinated by the cryptocurrency and bought some Bitcoin for himself. As the market rose, he bought a navy-blue Rolls Royce worth $500,000. Online, he took the name Les Mis, after the musical and novel Les Misérables, in which the poor rise up to overthrow a corrupt and brutal government.

Bitcoin’s rise became parabolic. It started 2017 worth just below $1,000. Over the summer, its value broke $4,000. By mid-December, the value had soared above $19,000.

In New York City, an open-air Bitcoin market opened up in Union Square. People gathered under a statue of Abraham Lincoln, and they had backpacks full of cash and bid for the digital coins. The market, renamed Satoshi Square, and its participants were reminiscent of the first New York traders centuries ago, who gathered in open areas near Wall Street.

Bitcoin machines, called BTMs, began to appear. About four thousand were in use around the world by the end of 2018, with more than two thousand in the United States alone. In New York City, 110 stores offered a Bitcoin machine. One estimate claimed that five new Bitcoin machines were installed each day. Money could easily be deposited and then converted into Bitcoin in a digital wallet that was instantly accessible from anywhere in the world.

This BTM sits in a train station in Poland.

Those who were lucky—or smart—enough to take a chance on Bitcoin in its infancy grew rich. One twelve-year-old, Erik Finman, borrowed $1,000 from his grandmother to buy Bitcoin when it was $10 per coin. He was later offered $100,000, or 300 Bitcoin, for video technology he had developed. He accepted Bitcoin, and his wealth compounded. Finman, who hated school, convinced his parents to agree to a deal: if he made $1 million before he turned eighteen, he wouldn’t have to attend college. He won the deal.

Cryptocurrency holders, now worth more money than they had once dared to dream, became very protective of their identities. It wouldn’t take much for a person with a gun to simply demand their passwords. Journalist Nellie Bowles noted that, considering blockchain is supposed to provide security on the internet, people who hold cryptocurrencies appeared to be very insecure. “There’s a common paranoia among the crypto wealthy that they’ll be targeted and robbed since there’s no bank securing the money, so many are obsessively secretive,” she wrote. Conspicuous consumption of wealth was discouraged among cryptocurrency holders, though a few exceptions applied. Purchases of Lamborghinis—or Lambos—were celebrated.

As Bitcoin prices rose, some jubilant holders planned to cash in, only to find that they had lost their private keys. One IT worker mined over 7,500 coins in 2009. “There were just six of us doing it at the time,” he noted, “and it was like the early days of a gold rush.” He stored his private keys to the coins on a hard drive that sat in his desk drawer. “Four years later, I had two hard drives in a desk drawer. One was empty and the other contained my Bitcoin private keys,” he recalled. “I meant to throw away the empty drive—and I accidentally threw away the one with the Bitcoin information.” By that time, his Bitcoin were worth $60 million. He begged his town to let him excavate the landfill where his hard drive was likely dumped. They refused.

Another Bitcoin holder, Mark Frauenfelder, spent $3,000 on 7.4 Bitcoins that he stored on a hardware wallet, a secure hardware device. As part of the security procedure, the wallet, called Trezor, generated twenty-four random words that he wrote down on a piece of paper and stored in his desk drawer. If he lost the Trezor, he could simply get a new one and use the twenty-four words to access his account. Just before a trip to Tokyo, Frauenfelder decided to put the paper beneath his daughter’s pillow in case he died in an accident. Bitcoin was rising fast, and he wanted his daughter to have access to the money. His daughter, however, was in London at the time and didn’t return for another week. In the meantime, his cleaning service went through the apartment, found the piece of paper with obscure names all over it and threw it away.

When Frauenfelder discovered the error, he thought it would be a minor inconvenience. He still knew his PIN, which would allow him to generate a new account and transfer the Bitcoins over. But when Frauenfelder tried the PIN, Trezor kept rejecting it. Frauenfelder tried dozens of variations. Nothing worked.

“I felt queasy,” he recalled. “After my sixth incorrect PIN attempt, creeping dread had escalated to heart-pounding panic—I might have kissed my 7.4 Bitcoins goodbye.”

Frauenfelder continued to try PINs; he kept failing. “This decentralized nature of the Bitcoin network is not without consequences—the main one being that if you screw up, it’s your own damn problem,” he noted ruefully.

These stories, however, did little to suppress what had become an investing craze. The Long Island Iced Tea Company changed its name to Long Blockchain Company. Its stock rose 500 percent in a single day.

A blockchain game allowed users to produce, or breed, a cryptokitty—a computer graphic image of a cat. Because each image was unique, scarcity occurred, which drove up prices. Users could only pay via Ether, and one kitty, Dragon, reportedly sold for $170,000.

These are some examples of cryptokitties. Each kitty is a unique combination of features, making it hypothetically valuable.

Jonas Lund, a thirty-four-year-old Swedish artist, used blockchain to create 100,000 Jonas Lund Tokens (JLTs). He gave these tokens to a board of trustees, who used them to vote on what artistic and professional steps Lund should take. In one instance, Lund had four ideas for artistically transforming a piece of plywood: with an engraving, with metallic gray paint, with pictures of birds and bullet points explaining his process, or with paint and then fire “in a controlled way to create something very fragile.” Lund asked his board of trustees what he should do. They used their tokens to select the third option: pictures of birds. This selection will correlate to 1,041 tokens in the future. When someone buys the piece, they will be awarded the tokens, which they can then use to vote on the direction of Lund’s art.

With the blockchain-based tokens, Lund is simply formalizing what he sees as the personal, market, and community forces that influence art. Lund has given the tokens to people he knows, and some people were awarded tokens for buying his work. He also offers tokens to individuals who invite him to a talk, tweet about him, or use the hashtag #jonaslundtoken.

Everyone, it seemed, was talking about cryptocurrencies. But regulators remained skeptical. Crypto supporters, or cryptobros, urged the SEC to approve a Bitcoin exchange traded fund (ETF). “Adapt or die,” wrote one supporter. “Approve Bitcoin ETF and take the leading step for advancing the human race through the revolutionary technology we have been gifted.”

In July 2017, Ethereum was two years old. The price of Ether had risen from $8 to $400 in the first half of 2017, giving many people plenty of reasons to celebrate. An anniversary party for the coin drew three hundred people to a rooftop bar in Manhattan. Michael Casey and Paul Vigna attended, noting that they had witnessed many of the booms and busts in the city, from the dot.com craze in the late 1990s to Bitcoin. The scene, they said, was virtually the same.

“The energy of the crowd was palpable,” the journalists wrote. “The expectations of instant wealth unmistakable. Like most other tech breakthroughs, this one contained a mixture of utopianism and capitalism. Some people wanted to change the world. Some wanted to get rich. Many imagined they could do both.”

In 2017 initial coin offerings (ICOs) drew exuberant attention. Digital companies issued their own coin, and investors hoping to enjoy the returns realized by the first Bitcoin owners piled in. These companies raised $6.6 billion in 2017. Dozens of coins or tokens appeared, many of them variations on Bitcoin called altcoins. EOS, “the most powerful application for decentralized applications,” raised $4.2 billion. TaTaTu, “social entertainment on the blockchain,” attracted $575 million. Dragon, “the entertainment token,” raised $420 million.

In 2018, a Ukrainian social media network wanted to raise publicity for its ICO. It decided to send four crypto enthusiasts to the top of Mt. Everest where they would bury a hard drive containing cryptocurrencies at the summit. Two of the climbers never reached the summit. The other two reached the peak and were trapped in bad weather. They were later evacuated and treated for frostbite. One Sherpa accompanying them died. The company, ASKfm, reported that the hard drive supposedly had 50,000 worth of cryptocoins on it, and they encouraged others to search for it.

Stunts like this attracted negative publicity, and many critics continued to see cryptocurrencies as little more than a tool for criminals. People hesitated to use them as a medium of exchange because, according to economist Martin Wolf, “law-abiding people and businesses do not want to own assets that are, by virtue of their anonymity, ideal for criminals, terrorists and money launderers.”

Other critics focused on cryptocurrencies’ volatility, as well as the controversies that hit the more established digital coins, especially related to security. “None of that is encouraging for anyone who needs a currency to reliably pay for groceries and rent,” noted columnist Lionel Laurent.

A Fork in the Blockchain

As Bitcoin transactions became more frequent, they also became more expensive. Bitcoin transactions were hardwired to be limited to one megabyte. Because of this small size, the blockchain network only processed seven transactions per second. By comparison, credit card companies can handle more than fifty thousand transactions per second. As more and more Bitcoin transactions were processed, the network became clogged.

Some users offered miners higher fees to include their transaction in a block. By 2017 users were paying miners an average of five dollars per transaction. This made small transactions prohibitively expensive—buyers of movie tickets or a cup of coffee would have to pay five dollars extra. Worse, to blockchain supporters, the preferential system was starting to resemble the system of intermediaries—banks, agencies, and so on—that blockchain was trying to replace. Users who wanted to pay cheaper fees found they had to wait hours, or even days, to have their transactions processed.

An obvious solution was to make the transaction sizes larger, but miners protested that these would cost more to process. If costs rose, fewer miners would participate, potentially making the system more vulnerable to manipulation. One side wanted greater ease and convenience. The other stressed security.

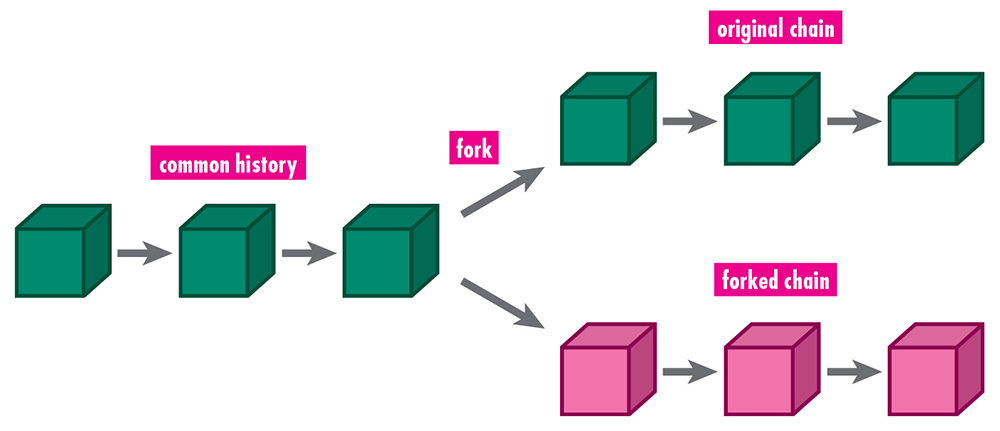

The debate grew acrimonious. One group proposed a “fork” to Bitcoin. A fork occurs when two miners solve the proof of work in a blockchain almost simultaneously, resulting in a discrepancy in the ledger. In effect, the two transactions present a fork in the ledger, offering two potential outcomes for the ledger to follow. At this point, a consensus mechanism in the community selects the most accurate transaction, leaving the other transaction to be ignored. The fork is then resolved.

Forks, however, can allow the community of miners and nodes to effectively change the rules of the blockchain. The challenge is to get the blockchain community to agree to the change. After all, there is no centralized decision-making body that can simply order everyone to obey its decrees. Rather, the community has to come to a consensus.

Forks can be either soft or hard. In simple terms, a soft fork limits a blockchain’s rules going forward, while a hard fork expands them. A soft fork is much like an upgrade to a piece of software. Just as an upgraded computer can still run older versions of software, the blockchain can still work with miners and nodes who haven’t upgraded. A soft fork only requires a majority of a blockchain’s users to approve. A hard fork, however, is more difficult because it splits the blockchain into two incompatible chains, one that follows the old rules and one that follows a new set of rules. As a result, a hard fork requires unanimous agreement from a blockchain’s users. Otherwise, two different timelines for a blockchain will come into existence. In effect, one group will observe one set of rules, while the other will obey the other set.

This diagram shows how each branch of a blockchain fork shares a common history, but one branch will follow a new set of rules, while the other follows the original rules. In a hard fork, the rules are so different that the two chains are incompatible.

One software developer proposed a soft fork to the Bitcoin blockchain that would make it more efficient to process more content, effectively doubling its capacity. The fork would also allow Bitcoin to be used on a new network called Lightning. The Lightning Network allowed users to sign contracts that enabled them to use two-payment channels according to a preestablished balance. More important, the system allowed users to transfer funds to third parties without the need for miners. Thus, Lightning could allow any number of transactions without miners’ fees.

The Bitcoin community considered this solution. Some miners strongly opposed it, with one group in China leading the resistance. They didn’t want to lose their fees. Others thought that Lightning transactions, which are harder to trace than those on the blockchain, would draw a crackdown from the Chinese government. The Chinese government opposed any transaction it couldn’t monitor.

In May 2017, more than fifty Bitcoin companies across the globe, including cryptocoin businesses, exchanges, vendors, and service providers, came together to try to resolve the impasse. They drafted a document called the New York Agreement, in which they agreed to work together to improve technology, communication, and coordination to increase the capacity of blockchain to support a higher volume of Bitcoin transactions.

Through this agreement, the volume of Bitcoin transactions doubled. However, another group sought an even higher threshold. On August 1 a new cryptocurrency was introduced: Bitcoin Cash. This currency represented a hard fork from Bitcoin, and thus the two currencies were mutually incompatible. Worse, the agreement to increase Bitcoin’s capacity ultimately collapsed in November 2017 when a necessary consensus could not be met.

To some observers, the angry debate, the inability to agree, and the chaotic proposed solutions proved that cryptocurrencies were too unstable and unmanageable. But others concluded just the opposite. Bitcoin and the blockchain ledger had proven to be enduring. It couldn’t be changed, even by powerful participants with significant resources.