There was an inherited love of the land in Jeeter that all his disastrous experiences with farming had failed to take away.

—Erskine Caldwell, Tobacco Road

“This is what Hyde Park looked like when I was young.” It was early evening in mid-October. I sat in the backseat of the Utley family’s midnight blue Buick as we rode through Waynesboro, Georgia, about thirty-five miles south of Augusta. In between rows of Georgia pines, long, dusty fields dotted with light gray puffs of cotton framed either side of the one-lane road. Every so often, we passed a cluster of houses surrounded by wide green lawns. Reverend Charles Utley, fifty-three, a minister and middle school guidance counselor, drove the car and narrated. Next to him sat fifteen-year-old Anthony Utley, a tall, muscular boy who played basketball and sang in his high school choir. Like many kids who spend a good bit of time in the country, Anthony had learned to drive several years earlier. In typical teenager fashion, he frequently remarked on his father’s skills behind the wheel. Utley’s wife, Brenda, a second-grade teacher, sat next to me on the backseat. We chatted about Demetra, the Utleys’ oldest child, who lived in Ohio while she pursued a master’s degree in speech therapy. We were on our way to Bible study at the Utleys’ “home” church, somewhere on the outskirts of the town (the main intersection of which consisted of two gas stations, a barbecue pit, a hotel, and a McDonald’s). As we got closer to the church, Reverend Utley proclaimed that we were in “Utleyland,” and the scattered homes we passed in the fading light were those of his relatives.

Like many of Hyde Park’s original settlers, Reverend Utley’s parents moved their young family to Hyde Park from Waynesboro in the mid-1950s in search of better job opportunities. As we drove through the broad green fields of rural southeast Georgia, Utley continued to compare the landscape to the Hyde Park of his childhood:

Well, Babcock [an industrial ceramics factory] was there. The power plant was there, but it wasn’t as large as it is. The rest of it was just beautiful landscape. Just land, trees, and sage fields. Where the junk-yard is, that was the area that we could plant. Nothing there.

Utley’s description highlights how, for its original settlers, Hyde Park combined the best of two worlds: surrounded by trees and fields, it appeared bucolic, but, just six miles from downtown Augusta, it was also close to the many job opportunities that the city’s growing economy promised. Relocating to Hyde Park, then, gave its residents the chance to take a giant step toward a prosperous future while keeping a toehold in their rural pasts.

The story of Hyde Park begins in the middle part of the twentieth century with the hopes and dreams of its original settlers. These former sharecroppers were the first in their families to own property and build equity to pass on to future generations. However, their dreams came to a crashing halt in the 1990s when residents discovered that nearby factories and hazardous waste–generating facilities had contaminated their land, potentially endangering their health and making their homes almost impossible to sell. For Hyde Park residents, this turn of events resonated with a history of struggle and discrimination.

Clearly, people address environmental problems according to how they conceptualize and understand the “environment.” Anthropologists Michael Paolisso and R. Shawn Maloney, for instance, illustrate how Maryland farmers viewed the environment as something that could never be fully understood, quantified, or regulated, whereas environmental professionals believed that science could both diagnose and resolve the region’s environmental problems. In both cases, professional identities were the lenses through which people viewed the environment.1 In Hyde Park, residents’ conceptions of the environment and land were shaped by race and class identities. Yet in this case I found that “land” and the “environment,” rather than appearing as synonymous terms, were almost antonyms.

Although Hyde Park residents had a long history of interacting with the land as farmers and rural residents, they had traditionally been quite removed from the environment as a movement. Historian Michelle Johnson explains that, for African Americans, the land has generally connoted concrete natural resources. The environment, however, has remained a “nebulous concept” that is not often part of everyday discourse, particularly because it is seen to be a white, middle-class concern.2 In recent years, however, a formerly “nebulous environment” has become all too real for hundreds of African American communities as they realize that their neighborhoods are contaminated. This chapter illustrates how the environment entered Hyde Park residents’ consciousness along with news of contamination, coming to mean something poisonous and discriminatory from which they needed to be saved. Whereas the land had represented the American Dream of ownership and a hope of overcoming racial discrimination, the environment represented the very obstacles that discrimination imposed against achieving that dream. Once they characterized the environment as a site of racism, activists added it to their traditional social justice agendas. They then expanded their definitions of the environment to include all the resources to which they lacked access (i.e., housing, schools, and police protection).

People infuse their physical surroundings with memory, experience, and history, and these interpretations are often a crucial inspiration for collective action. When people’s places are threatened, the force of the meanings and identities that they have ascribed to them transforms into powerful forms of activism.3 In Hyde Park, residents’ cultural experiences seeped into the land on which they lived and nurtured a strong community identity, which fed their activism. However, residents’ attachments to place also became quite complicated by the end of the 1990s.

Gardens? Yes, we had a pretty garden. Grew turnip greens, collards, cabbage, butter beans, string beans, okra …

When the Utley family moved to their new house in Hyde Park, they found themselves in a burgeoning neighborhood, replete with opportunity. Men could walk to work at Merry Brothers, as well as to Babcock and Wilcox ceramics factory, Piedmont Wood (later, Southern Wood Piedmont), or a new Georgia Power plant. Women could take the bus a few miles into Augusta’s “Hill” section to work as domestics. Moving to Augusta, then, offered families a double wage and, with it, a chance for economic mobility. Perhaps even more important than the promise of economic opportunity and dual incomes, however, was the fact that, for fifty dollars, the African American farm laborers of Waynesboro and other nearby rural areas could finally acquire their own piece of land. As Charles Utley explained,

A lot of families moved in that were [from] the rural areas. Because in the rural areas, you couldn’t own the land—you were crop sharers [sic]. And that was the reason my family moved here because otherwise they would never have the opportunity to purchase the land. They had to sharecrop it. And they had saved up money to move to this area.

Landowning is a goal for many Americans, but for the Utleys and their neighbors, it had a particularly intense meaning, given the fact that they had come directly from the harsh sharecropping realities detailed in the last chapter.

Moving to a neighborhood like Hyde Park was thus attractive for both practical and symbolic reasons. On the practical side, it was close to a number of industries, and one could buy a substantial portion of land for relatively little money. Of course, one of the primary reasons that the land was cheap was that it was undesirable. Hyde Park is only minutes from Phinizy Swamp, and “the swamp” was a common and well-founded nickname for the neighborhood. But its marshiness also made the neighborhood relatively bucolic. In other words, moving to Hyde Park meant that former farmers did not have to leave their country lifestyles entirely behind. Charles Utley explained why Hyde Park appealed to its early settlers:

I would say 98 percent of people had a garden. Matter of fact, when we moved, we brought the cow, the hog and everything else. So you didn’t lose your country life in the city. Matter of fact, the idea was you could move to the city and keep your country life at the same time.

It is not by chance that Utley prefaced his statement by mentioning how many of his neighbors had gardens.

Gardens played an important role in early Hyde Park life, and they permeate social memories of the neighborhood. Almost unfailingly, when I questioned people about Hyde Park’s history, they immediately mentioned gardens. For example, when I asked David Jackson to tell me about his fondest memories of growing up in Hyde Park, he responded,

When we came out here we didn’t have problems with the land a whole lot. My daddy used to have a garden right out there. And we used to raise sweet potatoes, all kinds of good stuff out there. And it was good.

Other residents similarly remembered how, in the 1950s through the 1970s, large and bountiful gardens dotted the neighborhood. As one man who began renting a house in the neighborhood in the early 1960s said,

Everybody had a garden out here just about I know of. [They] planted a garden because people love to do that.

As this man commented, people love to garden, and gardening is an important part of American history and culture in general. But for the residents of Hyde Park, gardens took on particular significance, given their history as not-too-distant descendants of slaves and as sharecroppers.

Depending on the type of work they did and the hours in which they did it, slaves were sometimes able to cultivate “patches” of vegetables, which they harvested and possibly even marketed or bartered. In Georgia’s cotton belt, there is evidence that slaves traveled from rural areas into cities and towns to vend their vegetables.4 After the Civil War, as black farmers became more transient under sharecropping conditions, it was more difficult to grow gardens. But the ravages of the boll weevil and the Depression made self-sufficiency even more important, and sharecroppers struggled to cultivate even a meager garden. The ability to cultivate and maintain “patches” became a source of satisfaction and pride—by staking a claim and cultivating even a minuscule plot of land, slaves and sharecroppers were able to carve out an aspect of their lives that was not entirely controlled by their oppressors.5

Many years later, in Hyde Park, gardens continued to symbolize security, pride, and self-reliance. For example, Arthur Smith recalled how his father would share the produce from his garden with friends and relatives:

And the crops so good, you would give part of your garden to other people. I remember my aunts coming down and picking greens out of my father’s garden and other crops.

Smith’s statement implies that having a bountiful garden with enough produce to share was a status symbol. Importantly, Hyde Park residents only occasionally spoke of the grocery money that garden-tending saved them or the sustenance that garden produce provided. More frequently, they emphasized the degree to which a good garden was a source of pride. Smith explained,

You know the gardens, they were like the pride of the men that lived in this area. Part of feeding your family.6 I think that’s part of the responsibility of manhood that I was taught. You know it was nothing new, certain times of the year, to see my father out plowing his field. He had a little roll plow that had a wheel and he would break the lanes up.… It was nothing unusual to see collard greens, tomatoes, okra, squash, watermelon. I remember big plum trees, fruit trees, all types. And each house had their own garden.

MC: Only men worked the gardens?

AS: I’d seen ladies hoe, but it was like, “I’m Arthur Smith and this is my garden and this is my wife.” It was a man thing.

Smith’s statement ties gardens to male identity. Gardens symbolized not only a man’s ability to provide for the family but also his autonomy. Whereas many of Hyde Park’s men moved from one factory or laboring job to another, subject to the whims of their employers and the economy, their gardens were stable, productive, and, for the most part, under their control.

For Hyde Park residents, gardens also symbolized racial progress and a chance to salve the wounds of slavery. Because they had grown up sharecropping on former plantation lands, Hyde Park residents lived in particularly close proximity to slavery’s ghosts. Possessing and cultivating their own land allowed African Americans finally to own the products of their labor. Community activist Terence Dicks explained,

I think [southern African Americans] have a point of view that they are after, all of this, entitled to, you know, that American culture that we sacrificed and slaved for and everything.… Some people … that’s the only thing they ever worked for and the only thing they ever had, that’s all they got to show for a life of misery, toil, and drudgery.

Owning land thus provided an enduring sense of security that had been denied to African Americans during years of enslavement and exploitation.

In her exploration of return migration, a growing trend among northern African Americans who move back to the rural South, anthropologist Carol Stack similarly argues that for African Americans, owning land promised the kinds of security and liberty that were denied to slaves. She writes,

The appeal of God’s little acre crosses all bounds of race and time, but the urgency could seem shrill for African Americans. If security and liberty were to be found anywhere, wouldn’t it be under one’s own roof, safe on one’s own land?7

Stack finds that even several generations after sharecropping, owning land in the South became a metonym for recovering and re-creating history. According to Stack, unlike past migrations of African Americans northward, return migrations are motivated not by economics but by “a powerful blend of motives” that represent “the chance to start something new, to remake the South in a different image.”8 Hyde Park’s settlers and the children of its settlers similarly viewed landownership as a chance to remake the past.

Part of this “remaking” included former sharecroppers’ chance to build real equity to pass down to future generations. Long-term resident Bernice Jones moved from Waynesboro to Hyde Park in 1954. Jones explained,

This is a neighborhood where people who were basically farmers and other people who had probably done sharecropping and who had never owned property came together buying property with the idea that they were going to buy something and build homes to have for their children to be raised in.

Real estate does more than provide equity for current and future generations; in many ways, it acts a linchpin for economic and social opportunity. Because land- and homeownership open doors to better education, employment, safety, insurance rates, services, and wealth, barriers to homeownership effectively bar people from social mobility. In marking the first step on the road to prosperity, homeownership often acts as a “key benchmark” in the story of individual African American progress.9

Owning land thus gave Hyde Park residents a chance to rewrite a history of racial subordination in a number of ways, all of which converged on the fifty-by-one-hundred-foot plots of swampland that composed Hyde Park. Together, the land and the opportunities it promised became prime ingredients for the American Dream. As Arthur Smith described,

These houses were bought with sweat and tears. When I say that, I mean sacrifice. It’s easy to say, “I’m going to live here and pay rent,” but these people wanted something in life. This was my father’s first home and my Uncle C.E.’s first home and many other peoples that moved out here. This was the first opportunity for them to live the American Dream, buy a piece of land, and “build me a home and raise my family and then leave it for my children.” That’s part of the American Dream in this great country.

As Smith indicated, by becoming homeowners, Hyde Park residents achieved new status as Americans.

Homeownership also shored up this status for future generations—another critical part of the American Dream. Anthropologist Constance Perin argues that while renters in the United States are seen as flighty, irresponsible, and itinerant, homeownership constitutes a social category equated with perfected citizenship because it signals having earned the trust of a bank, the sense to invest wisely, and the desire to accrue equity.10 For Hyde Park residents, owning homes and land represented a chance to join the American mainstream and to claim their place as full, and even ideal, U.S. citizens. In the early 1990s, however, news of contamination stunted the future possibilities that landowning promised. Now homes were unmarketable and gardens were toxic. Thus, the soil in which Hyde Park residents had instilled their American dreams became the very source of their dreams’ destruction.

People used to make gardens. I had a good garden. Now they can’t make anything. From the contamination, I guess.

In 1998, memories of gardens were bittersweet. Some residents claimed that gardens became too difficult to grow as industry increasingly encroached on Hyde Park in the 1970s and 1980s. David Jackson described how as the junkyard behind his house grew, his father’s garden suffered:

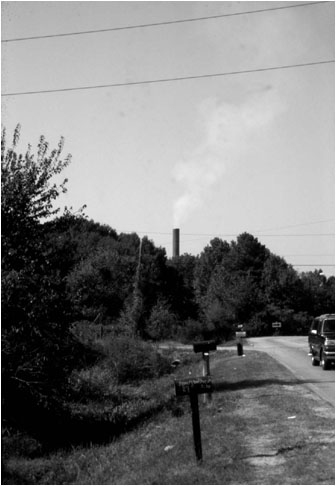

Entering Hyde Park on Dan Bowles Road, 1999. Photo by author.

But then when that junkyard moved in there and all this other stuff came in here, the property just went nowhere. You could plant something that’s rotten right there before you. When it’s trying to grow, it’s rotten.

Jackson’s account of the demise of his father’s garden is especially poignant when contrasted with his earlier description of it in its heyday. For Jackson, quitting the garden marked a significant turning point in his memories of life in Hyde Park.

Other residents faced a similar turning point in 1991, when the University of Georgia (UGA) Cooperative Extension Service for Richmond County tested produce and soil from Hyde Park gardens and found elevated levels of arsenic and chromium. The director of the Extension office later went on record as stating that he would not eat anything from a Hyde Park garden. Subsequent analyses of the test results varied (UGA scientists advised against eating from gardens, while the Richmond County Health Department contended that the food was safe for ingestion); but the results alarmed residents, and almost all decided to let their gardens die.11 Thus, contemporary memories of gardens were tainted with fear as residents wondered whether and when their health would bear the effects of having eaten garden produce. Ruth Jones said, “When they said not to eat anything, we stopped. We had a beautiful garden.” With very few exceptions, the vegetables and fruits that had once been the pride of the neighborhood were left to wither, uneaten and unharvested.12

Once contamination was discovered, all kinds of neighborhood memories became similarly associated with health worries. For example, prior to 1970, residents did not receive city water, instead using outdoor pumps connected to underground wells. However, after some reports concluded that both Hyde Park’s groundwater and soil were contaminated, residents feared that the water they had pumped had also been filled with toxic chemicals.13 Although narratives about the backyard pumps usually began with the kind of humor that comes from talking about “the old days,” they often turned to anxieties about whether the water had been toxic. Residents also now worried about having attended family barbecues on the SWP site. Wives of SWP workers wondered not only about their husbands’ health but also the fact that, back then, they had washed the men’s work clothes by boiling them.

Moreover, before gas lines were installed in the neighborhood (also in 1970), Hyde Park residents had cooked and heated their homes with wood-burning stoves. A common chore for neighborhood children was to go into SWP’s field, gather leftover creosote-treated wood chips, and take them home to burn in those stoves.14 Charles Utley remembered,

We would get the firewood from the chips that they would use to make the wood, and it was easy to burn so we would take that, and we would put it in the heaters and we would heat with that.

However, as Robert Striggles explained,

You see when we was burning that wood, we didn’t know that it was harmful to us. We was burning creosote. We didn’t know … creosote was a cancer-causing agent.

When residents realized that the wood chips contained creosote, another narrative about Hyde Park’s “old days” shifted from emphasizing pride at overcoming hardship to worry over health.

The poisonous chemicals seeping from surrounding factories also had a dramatic effect on Hyde Park residents’ community identity. As David Jackson said,

When they come up with that stuff about pollution and everything else—that killed it. Killed it. Ain’t nobody doing nothing to try to upgrade or do nothing. It ain’t like that anymore. We’re still just downgraded. And people can’t have a say or nothing now … nobody selling because nobody wanting to buy nothing. They aren’t going to pay that kind of money for something contaminated.

Jackson’s statement about still being downgraded illustrates the degree to which Hyde Park residents identified with their neighborhood. In some ways, the land had become a metonym, standing for Hyde Park people. In her book on working-class residents of a midwestern city, anthropologist Rhoda Halperin argues that neighborhoods are not just localities in which daily life occurs but places where “threads of identity … are woven from memories of work, of family and of neighborhood goings-on.”15 In Hyde Park, owning their own homes and cultivating their own land had once identified Hyde Park residents as people who had achieved a particular goal. After 1990, however, the neighborhood’s reputation was “downgraded” as it became associated with contamination.

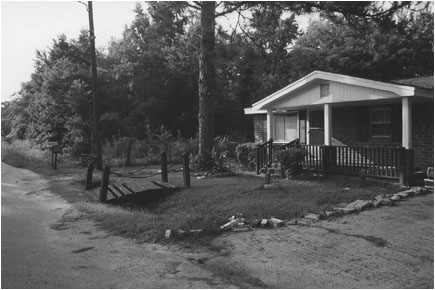

Similarly, other Augustans now associated Hyde Park with decline and destruction. Accordingly, as they waited for relocation funds to come via their lawsuit or the federal government, many Hyde Park residents stopped investing in their homes, and the neighborhood became increasingly run-down. By 1998, a significant number of houses had peeling paint and overgrown lawns, and ditches were strewn with litter. Thus, as the neighborhood declined physically, residents’ pride in it also declined, further “downgrading” their community identity.

House on Horton Drive, 2003. Photo by author.

Importantly, community identities are never uniform, and members of a community rarely agree on all aspects of an issue. On the one hand, some Hyde Park residents firmly believed that their neighbors should spend only the bare minimum necessary to maintain their homes and keep the area looking clean, since they were working so hard on relocation strategies. In this view, relocation might become a reality at any time—why build up your home if you were about to leave it any day? On the other hand, less hopeful residents insisted that as long as they were stuck in Hyde Park, they wanted to live in the nicest home they could afford. David Jackson, for example, told me,

If work need to be done around here, I ain’t going to wait until somebody say that we going to relocate y’all to do it. My house needs to be a decent place to live so I do that.… So people say, “Oh, don’t do nothing to your house.” What do you mean? I live in that.

Porch sitters, 1999. Photo by Maryl Levine.

In 1998, residents thus faced a conundrum: Should they continue to live in downgraded circumstances and wait for relief, or should they try to make their homes as livable as possible, despite contamination?16

Whether or not residents chose to invest money in home improvement, after 1991 Hyde Park did decline both physically and in terms of its reputation. Almost all Hyde Park homeowners agreed that selling was virtually impossible once news of contamination had spread throughout the area. Even though studies on whether contamination had affected residents’ health had varied widely, property law bound Hyde Park residents to disclose the possibility of contamination. After 1991, most homeowners felt trapped on their potentially poisoned land. Bernice Jones, a retired teacher in her fifties, explained this catch-22:

People invested in homes, and now they can’t sell them for anything like what they paid for them or put into them. Ours will be paid for in November, but where will we buy another comparable house? How will we start over at this age?

Where it had once promised prosperity and the opportunity for self-sufficiency, land in Hyde Park now represented disappointment and the dashing of the American Dream.

These phenomena—tainted memories, the inability to sell a home, the destruction of a dream, and the loss of community—are all typical ways that toxic exposure socially contaminates a community, according to environmental psychologist Michael Edelstein. Edelstein finds in these places an “inversion of home” or the “negation of the hopes, dreams and expectations that surround the institution of home in American society.”17 Moreover, Edelstein argues that the closer people are tied to home (i.e., those who work there or who are retired, home-bound, and/or members of clustered extended families), the more acute the effects of contamination. Hyde Park shows us two additional factors in this sense of loss: poverty and racial history, both of which tied Hyde Park residents to their land in profound ways.

From slavery to land loss to sharecropping, owning land symbolized overcoming a history of racial exploitation, as well as a stab at a middle-class life. The chance at ownership thus transformed land from a site of racial oppression into a site for racial autonomy, freedom, and belonging. It is no wonder, then, that Hyde Park residents connected the contamination of their land to their history of racial struggle. As the environment flooded Hyde Park residents’ consciousness, it rode in on a tide of destructive chemicals and years of discrimination.

We didn’t really think about the environment before. We was just too busy trying to live.

Mentioning the term “environment” to adults in Hyde Park prompted them to tell of the dust that covered their walls and reappeared as fast as they could wipe it off. They spoke about the toxic release sirens coming from Thermal Ceramics that sometimes blared for eight hours, forcing residents to go to the mall or the movies to escape the noise (let alone the toxic release). They told of how they had permanent tickles in their throats and how their children were never far from their inhalers. They described how their children could not dig in the dirt around their houses or play in the ditches that lined the streets of their neighborhood. For the residents of Hyde Park and for the activists of HAPIC, the environment was not something to be protected from human intervention and conserved for the preservation of wildlife.

Rather, their environment was poisonous, and they needed to be protected from it.

Hyde Park residents had always connected the fact that their neighborhood lacked urban resources such as adequate police protection, litter control, and refuse disposal to its racial composition. In 1968, they formed the Hyde and Aragon Park Improvement Committee as a civil rights association to demand city water, sewage, streetlights, and paved roads. Although they had deep connections to the land, with very few exceptions, Hyde Park residents paid no attention to environmentalism or environmental matters per se until they heard that their air, water, and soil might be poisoned. Immediately, residents connected that pollution to racial discrimination. They had diverse conceptions of where this discrimination came from, but for all of them the “environment” was attached to words like “racism” and “injustice.”

Even HAPIC’s president, Charles Utley, said that before 1990, he “didn’t even think about [the environment].” One activist reasoned that the environment was “not really an issue because most people just were not exposed to it.” Some residents said that they had heard some things on TV, but most agreed that they never cared about it very much.18 Blacks in the South are all too aware that they face a long list of institutional discriminations, but they have been slow to realize that the siting of hazardous waste facilities is on that list. Not only have African Americans historically viewed the environment as a white, middle-class concern, but also the employment opportunities that these industries promise often overshadow their detrimental environmental effects. Sociologist Robert Bullard describes how residents of minority areas were hesitant to question corporate and governmental polluters because they did not want “to bite the hand that fed them.” In the “black belt,” African Americans are more likely to be unskilled, poorly educated, and intimidated by large corporations.19

In areas like Augusta, intimidation worked well. One man told me that the reason residents stood by as numerous factories located and expanded in their neighborhood was that “people are afraid of the white man.” In another example, Charles Utley explained,

There was no one to tell the community people, you shouldn’t be there. Or to be a watchdog for what chemicals they were producing. It was a way of life that blacks were used to going to work, doing what they were told and not asking why. As a result, damage [was] done to their health and the environment.… They’re [treated like] second-class citizens anyhow.

Although Hyde Park’s own history of activism and fighting against institutional racism belies some of these statements, they do highlight the difficulties of fighting environmental racism, even in areas where education and income levels are mixed. First, confronting large, faceless corporations may be more intimidating than opposing local governmental officials. Second, during the civil rights era, activists challenged blatantly racist laws, but environmental racism was an unexpected form of discrimination, and one that was not easily identified or readily recognized.

For many years, Hyde Park residents had resigned themselves to the conditions that their factory neighbors imposed on them as a part of neighborhood life. They grew used to the residue that covered their cars, the oil that often appeared on the surface of ditch water, and the fact that their water sometimes “had an odor to it.” Annie Wilson, one of Hyde Park’s first residents said,

That water one year, it was stinking. And we really hadn’t paid it that much attention.… In Aragon Park, my niece was living over there, one time, that water was so stinking they couldn’t take a bath in it.

Some residents, on the other hand, said that they suspected something might be wrong in the neighborhood, but because they felt they did not have much evidence to back them up, they never addressed it. David Jackson remembered,

My yard used to flood out more than anybody in this whole area because all the water from the junkyard would flow right in my yard. And when it leave, it leave all kinds of grease-filled and black-looking dirt with the oil and stuff that just shot up in here. But for years, we know something wrong, but we don’t know exactly what it is.

Some female residents said that they had begun to notice that their neighbors had certain health problems in common. For instance, Johnnie Mae Brown, a sturdy woman with graying hair, was also an active and veteran HAPIC member. Brown quit her job at Fort Gordon long before she was eligible for a pension so she could care for her aging and sickly mother and uncle (who worked at Babcock and Wilcox for twenty years). Brown said,

We knew that there was something, but we didn’t know what it was.… The children were breaking out with these different rashes on their skin. A lot of people in the neighborhood died from cancer. I had a sister to die. She was only thirty-two years old.

Brown’s experience follows a gendered pattern of environmental justice awareness that is especially common among working-class women. A number of environmental studies scholars posit that women activists are prevalent in the environmental justice movement because they tend to be more closely aware of and affected by family illness.20 I do not have the space to discuss this issue in detail here, but in my interviews women frequently claimed to have “always” been suspicious of local health problems. Some people also told me that, before Mary Utley herself fell ill with heart trouble in the mid-1980s, she was gathering information on cancer rates in the neighborhood. However, widespread organizing around environmental issues did not begin until the early 1990s.

Until the institution of federal environmental regulations in the 1970s,21 SWP discharged its residual water into Rocky Creek and Phinizy Swamp, and it burned treated wood waste, producing smoke and fly ash. By 1979, in compliance with new federal regulations (such as the Clean Water Act), SWP had redirected its waste disposal and installed monitoring wells on the plant’s property. In 1983, those wells revealed on-site groundwater contamination from wood-preserving chemicals (including creosote, arsenic, chromium, and PCBs). Investigations over the next five years identified two plumes of contamination. One extended approximately two thousand feet from the plant along Winter Road, and another extended east along the old effluent ditch to New Savannah Road. Five years later, SWP decided to close its Augusta plant, partly because the soil and groundwater contamination could not be adequately remediated as long as the plant remained in operation.22

Residents of Virginia Subdivision were unsurprised at the plant’s closing. At the time, Virginia Subdivision was a mostly white neighborhood right on the border of SWP and across a field from Hyde Park. Several long ditches ran from SWP property through Virginia Subdivision and into Hyde Park. As early as the 1970s, residents of Virginia Subdivision had begun filing complaints with the Georgia Environmental Protection Division about a foul odor emanating from their drinking water and their backyard wells. They also documented the number of residents with cancer and were alarmed by the results.23 In response, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) conducted a health consultation in 1987. Its report discouraged residents from using well water and suggested that certain ditches were potentially contaminated.24 Residents of Virginia Subdivision also joined with several local companies that owned property around SWP and filed a class action suit seeking damages for trespass, nuisance, and neglect. In mid-1990, SWP’s parent company settled the lawsuit for approximately $8.6 million.

Although some Hyde Park residents claimed that their water had always tasted suspicious, unlike in Virginia Subdivision, almost all Hyde Park residents agreed that they did not seriously question the conditions of their neighborhood until around 1990. Around that time, a local environmentalist who monitored emissions from Thermal Ceramics claimed to have found PCBs and creosote running through local ditches and encouraged community leaders to keep track of pollution in the area.25 Even so, many of the Hyde Park residents I interviewed attributed the beginning of their environmental awareness to a large flood in 1990 that swept over Hyde Park and left in its wake a foul-smelling bluish white mud and houses full of corroded furniture. Johnnie Mae Brown remembered the “high water” of 1990:

Most people in the neighborhood didn’t even think about [the environment] until we had that flood. After the flood we knew that something was wrong because that water, everything that the floodwater touched, it was no good no more.

Ollie Jones also recalled,

That would have been about when that high water was … in the nineties.… My water was so high it was all in my porch and stuff, and a lady from Channel 12 was interviewing me about the contamination because of the water and all that and I said, yes, it’s been like that for quite a while cause the water would come up from the sewers and things. And that was when I first really got into it, you know.… [The water] had a funny color and an odor.

Ditch on Golden Rod Street, 2004. Photo by author.

Shortly after the flood, stories about the SWP closing appeared frequently in the local news, and residents also realized that the prison crews working on Hyde Park’s ditches had not been around for “quite some time.” Indeed, at least a year before the flood, Richmond County officials had halted ditch work in Hyde Park because they were worried about the possibility of contamination.26

Also around the time of the flood, HAPIC leaders first heard about the Virginia Subdivision lawsuit. Although the subdivision was adjacent to SWP, whereas Hyde Park was located about a half mile from the factory, it seemed obvious to Hyde Park residents that the ditches lining both sides of their streets carried water directly from SWP through their neighborhood. They quickly linked own smelly drinking water and foul-smelling mud to those ditches. Moreover, the same chemicals found in Virginia Subdivision were discovered within fifteen feet of Clara E. Jenkins Elementary School at Hyde Park’s entrance.27 And some Hyde Park residents alleged that they had seen SWP trucks dumping waste into nearby fields at night.28 Residents were then incensed when they were excluded from the settlement. Although they had not yet filed any legal actions against SWP, they believed that offering them a settlement would have been “the moral thing to do.”29 In addition, Virginia Subdivision residents had not included Hyde Park in their lawsuit. Because at the time Virginia Subdivision was a mostly white neighborhood and Hyde Park was an entirely African American neighborhood, Hyde Park residents interpreted their exclusion both from the original lawsuit and from the settlement as a clear-cut case of racism.

Just after the Virginia Subdivision settlement, Bill McCracken, a local attorney, approached HAPIC leaders and began organizing a class action lawsuit, asking African American civil rights attorney Harry James to join him. Along with HAPIC leaders, the two lawyers began signing residents on to the suit. Soon former SWP workers agreed to issue statements indicating that they had dumped waste into Hyde Park. McCracken and James also found a medical study produced by SWP that addressed the issue of skin cancer prevalence in dark-skinned individuals compared with that in fair-skinned individuals. However, finding enough proof to satisfy legal standards that SWP deliberately contaminated Hyde Park because its residents are black has never looked promising. The lawsuit, then, makes allegations similar to those in Virginia Subdivision’s suit (i.e., trespass, nuisance, and neglect). Connecting their strange, intermittent rashes, asthma, and cancers to environmental contamination led residents to categorize the environment as something dangerous and even deadly, in sharp contrast to their understandings of the land. It also catapulted them into environmental action.

I ran into one of the organizers of the Love Canal. And when we compared the Hyde Park story with the Love Canal, theirs was white and ours was black. And that was the biggest issue.

In 1998 and 1999, Hyde Park faced a twofold problem. First, some studies had shown, and residents certainly believed, that toxic chemicals had contaminated the neighborhood and threatened the health of those living in the area. Second, residents lacked the financial resources to move out of Hyde Park, and selling a house was nearly impossible. In addition, lawyers on both sides of the lawsuit continued to file multiple motions, which had the effect of delaying the trial date.31 Attorneys McCracken and James were working on contingency, so the time they could devote to Hyde Park’s lawsuit became increasingly limited as the years wore on. Eight years after filing their lawsuit, most residents had given up hope that they would ever see a legal victory. Despite the tireless efforts and indomitable spirit of HAPIC leaders, the possibility of receiving a governmental remedy for their situation also seemed bleak.

While Hyde Park residents faced the double whammy of being black and poor, they overwhelmingly agreed that racism, not classism, was the primary reason for their situation. For example, Charles Utley once told me that Hyde Park’s situation had “95 percent to do with race.” In numerous interviews, residents stated why they thought their neighborhood had been contaminated and why they had not received any help. Occasionally the initial answer was that Hyde Park was a poor neighborhood. Yet once I encouraged interviewees to be frank, or once my research assistant, Michelle, told them to “go ahead” because I was “okay,” they admitted that they felt race was “the biggest part” of the reason. The more residents I interviewed, the clearer it became that racism was the framework from which they viewed their circumstances. (It also became clear that residents were not entirely comfortable blaming their problems on racism in front of a white audience.) Certainly, Hyde Park residents believed that their neighborhood’s image as a low-income area contributed to their situation. Yet Virginia Subdivision’s settlement confirmed for them that the presence of white (if low-income) people had elicited a series of positive responses from the judicial system, which led to compensation. That Virginia Subdivision residents actually received very little did not mitigate Hyde Park residents’ sense of being discriminated against.

For example, I interviewed Ollie Jones, a bus driver for Richmond County Public Schools who had lived in Hyde Park for forty-two years, and his wife, Ruth, a thirty-year Hyde Park resident, in the large, immaculate living room of their trailer.32 Mr. Jones’s carefully ironed khaki shorts and plaid shirt barely hinted at the heat of the day. Mrs. Jones, wearing shorts and a T-shirt, had just gotten off from work cooking lunch at the Jenkins summer school and was a bit breathless from a morning spent with elementary school children on summer vacation. I asked the Joneses to name the reason for the Hyde Park situation, prodding them to be “frank.” Ollie Jones responded,

You want me to be frank with you? If this was a white neighborhood, now I’m being honest, government would’ve stepped in here and wouldn’t have been about two or three words said. Another thing is if this had been a rich neighborhood, it wouldn’t have been nobody in here, they would have moved them out of here. But most of the people are poor, black people.

Jones went on to compare his neighborhood to Virginia Subdivision:

If you look at [Virginia Subdivision] over there, for instance, the majority of the peoples over there is white people, right? And Piedmont is connected to this place too, but they were complaining over there, they didn’t hesitate, they bought them out. ruth jones: But they wouldn’t do that for us.

For the Joneses, when white people complained about contamination, SWP “bought them out.” However, when the black residents of Hyde Park complained, SWP ignored them. Totsie Walker agreed:

[Being black is] the biggest part. If we was in a mixed-up neighborhood, they would’ve done something. But you see it wasn’t. Now, you see, that’s the way I feel about it … they just don’t care, you see.

Other residents pointed out that, while not everyone in the neighborhood could be considered low-income, everyone in it was African American. Johnnie Mae Brown said,

Yeah, I think we’re black, low-income people in the neighborhood. And not everyone is on the poverty line, you know, but we’re still in the neighborhood. And I think it’s because we’re black first of all. That’s the most important. We’re black, poor people. And they just build anything they want around us and we don’t have no say so.

Brown’s statement highlights her perception of the powerlessness of blacks in Augusta, regardless of income level, profession, or homeownership.

Many fine books and articles enumerate the multiple and complex problems that contribute to environmental injustice. As a cultural anthropologist adding to this body of literature, I aim to explore in detail exactly how and when African Americans talk about race, especially in the context of the environment. All Hyde Park residents I spoke with believed that some kind of racism was the reason for their situation. Even the few residents who did not accept that their neighborhood was contaminated still believed that no one had responded to Hyde Park’s call for help because the people living there were black.33 For example, Deacon Saulsberry (who denied the presence of contamination) said, “It’s hard for the white people to say yes to something and stick to it.… They don’t want to help. They won’t help.”

Thus, while all residents attributed their situation to racism, the sources they named ran the gamut between specificity and ambiguity—some mentioned local government, some corporations, some federal policies, and some stereotyping. As described earlier, some of the factories and plants surrounding Hyde Park were there before it became a neighborhood. Yet some residents reasoned that it was because of racism that they could only afford to live in the midst of factories in the first place. Others answered that, although SWP and Babcock were there when they moved in, at least four other factories appeared over a thirty-year period. Arthur Smith pointed to racial stereotypes: “I think with Hyde Park and Aragon Park, it was the arrogance again of big companies saying, ‘those people are not educated. Those people do not vote.’” Other HAPIC leaders cited more systematic practices of racism, referring to their situation as “environmental apartheid” or “residential holocaust.” Charles Utley called it “a form of genocide.” For Utley, the “genocide” of environmental racism stems from a deliberate, planned, and systemized racism made up of both corporate greed and discriminatory political institutions. In this view, each aspect of the system facilitates the other—corporate greed initiates environmental racism, and institutional racism perpetuates it. The economic and social roots of racism thus go hand in hand in a tangled and mutually constitutive system of discrimination.

Indeed, environmental racism stems from complex causes. While naysayers argue that siting decisions are market driven, not deliberately racially motivated,34 even if corporations do use race-neutral criteria when they locate hazardous waste sites, or when a neighborhood grows up around existing hazardous sites, other kinds of institutional discrimination contribute to environmental racism and make it almost impossible for residents to leave and escape contamination. First, the generally white racial makeup of local zoning and planning boards gives African Americans little say in factory or incinerator siting decisions. Second, despite the Fair Housing Act and other civil rights reforms, realtors continue to steer African Americans toward existing “ghettos,” and mortgages and home improvement loans are allocated most often to white neighborhoods.35 Racially differentiated neighborhoods produce uneven property values—that is, black neighborhoods tend to have lower property values. In turn, our education systems, which are financed through property taxes, are vastly unequal. Poorer educations give African Americans less access to the kinds of jobs that would enable them to move out of a contaminated neighborhood. Finally, many of those who could move to a white neighborhood are reluctant to do so because of historical experiences of racism and persistent white antipathy toward integration.36 Again, all these factors make Hyde Park’s situation different from those of middle-class white neighborhoods, whose experiences of contamination are also tragic, but which do not necessarily face the added complications of historical, structural racism in America.

Across the country, African American environmental justice activists similarly insist that, whatever the complex chains of events that have led to their toxic situations, they result from long-standing racism. The overwhelming commonalities of these beliefs point to the continued salience of race for African Americans in the United States, especially for those who bear the brunt of racism on a day-to-day basis.

The environment? I don’t know, but it used to be awful.

In striking contrast to the lack of environmental concern in Hyde Park prior to 1990, in 1998, 79 percent of residents surveyed admitted to being “very concerned” about the environment.37 Yet the “environment” that residents referred to was of a specific nature—their dramatic introduction to environmental awareness had fixed residents’ associations with it as a dangerous, deadly, and racist entity. Residents thus created a framework for environmental organizing that resonated with their experiences as southern African Americans.

When I asked people about their environmental awareness prior to hearing about contamination, intending to find out whether they had been concerned about issues such as recycling, nature preservation, or endangered species, the answers I received referred only to contamination. As one man said, “The little I thought about it was my Daddy was talking about how his garden wouldn’t grow no more. Then I started thinking something was wrong.” In all my interviews with non-HAPIC leaders, only one resident, who had once worked at a recycling plant, spoke about the environment in global terms. Overwhelmingly, residents’ frame of reference for the environment was restricted to the dangers it presented. For instance, when I asked her to define the environment, Totsie Walker replied,

I heard lots about [the environment]. Sometimes it would be in the paper, but they’d block it out.… Some said arsenic, and some said this. Different things. [Those politicians] talk about it, but they never do anything about it.

Similarly, David Jackson defined the environment by proposing solutions to Hyde Park’s specific environmental problems. He said, “Pick up the trash. I would relocate, but you know it’s a lot of memories here. My Daddy worked hard to have this and I remember how hard he worked.”

In addition to defining the environment as a source of contamination, residents associated it with racism. For example, HAPIC’s treasurer, Melvin Stewart explained what most people in Hyde Park thought of the environment: “I don’t think it’s just chemicals, but a lot of people just think that. Racism is not just chemicals.” Although Stewart himself had traveled to a number of conferences on behalf of HAPIC and maintained a broader view of the environment, his immediate association of the words “chemicals” and “racism” with “environment” underscored the way the environment had come to be defined in the Hyde Park community. In turn, these definitions made the environment a locally salient issue.

Environmental justice means doing unto others as you would have them do unto you.

In the spring of 1999, I sat next to Arthur Smith in the crowded sanctuary of the Unitarian Church in west Augusta. For the first time for each of us, we were attending a meeting of the Augusta–Richmond County Sierra Club. This particular Sierra Club chapter acted more as an outdoor activity and hiking club than a political group and had not been very involved in Hyde Park’s struggles.38 In fact, of the fifty or so people at the meeting, Arthur Smith was the only African American. He leaned forward in his chair and jotted notes on the back of a flyer as we listened to Augusta’s recently elected mayor speak about his environmental agenda. The mayor’s talk focused on litter control and cleaning trash off roadways. During the question-and-answer period, Sierra Club members pursued his themes and asked about starting a mandatory recycling program, garbage pickup, and bicycle lanes. Next to me, Smith raised his hand. Somewhat startling the other meeting attendees, he stood to ask the mayor to explain his “theory about violence in the inner city.”

For Smith, it was perfectly appropriate to address inner-city violence at a Sierra Club meeting because violence was an environmental concern for his neighborhood. As noted earlier, in the 1980s and 1990s, employment rates in Hyde Park declined significantly, and drug dealing (mainly crack cocaine)39 became a fixed local industry. Every two or three months, I would hear that the sheriff’s department had staged some kind of “sting operation,” and the streets would clear for the next week or two. Eventually, however, the dealers would be back to business as usual.

Drug dealing certainly brought violence with it. Only a few weeks before the Sierra Club meeting, Anthony Ruffin, a neighborhood drug dealer, shot and killed his rival, Michael Young, who lived part-time at his grandmother’s house on Golden Rod Street. Seven years earlier, Ruffin and Young had gotten locked in a shoot-out until they were both on the ground and bleeding. After recovering, they made peace. However, one afternoon in early March 1999, Ruffin sneaked up on Young while he was lifting weights in his grandmother’s backyard and shot him several times in the back. After the shootout, Arthur Smith, a few other neighborhood activists, and I organized a prayer vigil and candlelight march to “stop the violence.” In gathering information for the event, we established that nine people had been murdered in Hyde Park over approximately twenty years, almost always related to drug selling.

The belief that drugs and violence were connected diminished residents’ feelings of safety. For example, since crack dealing took root in the 1980s, many senior citizens were afraid to venture out at night, and those residents who could afford them, installed alarm systems in their homes. Yet, aside from a few exceptions, violent incidents mainly arose from domestic disputes. For example, in 1999, one man set his ex-girl-friend’s porch on fire (no one was hurt), and another man stabbed his brother in the eye. Other than that, I heard about very few crimes. In fact, at one HAPIC meeting, attendees expressed their pleasure that basketball nets, installed the year before, had remained attached to their hoops, and no attempts were ever made to steal the four computers donated to the community center in the fall of 1998. Even so, most residents constantly worried for their own safety and that of their families and their possessions, especially when dealers were around.40

At the same time, drug dealers had grown up among Hyde Park’s elders. Describing the period when the dealers were operating outside her house, Johnnie Mae Brown remarked,

It was frightening; they had guns and all that stuff. But they was very respectful. They called me Miss Johnnie Mae; everybody calls me Miss Johnnie Mae. And they’d never disrespect me. If I’d go out there and tell them to move their car, they’d say, “Man you better move that car for Miss Johnnie Mae.” And they would be out there cursing and using profanity, and I’d be out there, “Hey, what’s y’all’s problem?” And they’d say, “I’m sorry, Miss Johnnie Mae.”

Some drug dealers also occasionally became involved in neighborhood activism. For instance, Arthur Smith told me that back in the 1970s, when drugs first established a toehold in the neighborhood, dealers would walk into Christian Fountain Church, place some money in the collection plate, and leave. A few years after I conducted my fieldwork, some of the neighborhood’s drug dealers decided to revive the softball league started by Mary Utley. In 1999, one local addict tried to revitalize another of Mary Utley’s institutions and hold a fashion show, with local children as models.

Drug dealing, then, was not an acceptable aspect of neighborhood life, but it was part of a much larger and more complicated picture. Many residents realized that drugs provided a singular access to revenue, and while they abhorred the negative effects of dealing on their neighborhood, they also ultimately blamed its stronghold on a lack of choice. Arthur Smith once told me, “I’m not going to go up to [those dealers] and judge them and try to stop them until I can give them a job.” Activism focused on drug dealing and violence, then, was as much about education and employment as about “cleaning up the streets.”

And efforts to “clean up the streets” were as much about crime as they were literally about trash and litter. In 1998, 65.1 percent of Hyde Park residents surveyed named trash and litter as a very serious problem in the neighborhood.41 Yet most people believed that no matter how hard they tried to keep the neighborhood clean, the city’s inattention to it undermined their efforts. For instance, Johnnie Mae Brown said,

I like to keep my street clean. If I see paper, I pick it up. And I know, sometimes I hire people to clean around the properties next to me. Clean the ditch. And every day I clean paper out of the ditches because the police, they come through here, but they don’t really control our area like they should. The only time they patrol it real often is when we keep calling them about the drugs being sold in front of our property. Then they will send somebody out and they will come around often.

For Brown, the city’s refusal to take care of its trash paralleled its refusal to help control criminal activity. Moreover, Hyde Park residents’ common concerns about trash and litter, and their efforts to stem it, belie stereotypes that link unkempt neighborhoods to lazy, apathetic, and unkempt neighbors.

All this discussion is intended to convey the point that activism in Hyde Park was broadly conceived—drugs, violence, education, employment, police protection, litter, and pollution were all tied together in an intricate knot bound up in historical discrimination. Thus, not only did residents define the environment as a civil rights issue, but all the civil rights issues HAPIC addressed had also become the “environment.” For instance, in 1998–1999, its activities included an after-school environmental education and tutoring program, computer training for adults, showing a series of videos on drug education, conflict management, and teen pregnancy, a prayer vigil and march to stop violence in the community, applying for environmental cleanup grants, and continuing to pursue the class action lawsuit against SWP. From this wide-ranging list, it is apparent that HAPIC continued its original mission to advocate for the civil and social rights of its constituents. As Melvin Stewart said, “HAPIC deals with whatever comes up—crime, drugs, contamination. Contamination is an extension of what [we’ve] already done.”

Although contamination had become HAPIC’s main focus, it did not preclude engagement in more traditional organizing activities. Charles Utley explained,

It’s like I tell the kids. The environment is everything you can’t see.… It is your home. It starts with your home as the world and narrows to your room and to your bed. It includes your messy bed, your messy room.

When HAPIC activists said that they wanted to clean up their environment, they meant that they were working to remediate the ecological damage left by toxic contamination, as well as the social damage left by a legacy of institutional racism. Arthur Smith elucidated,

[Environmental justice] is health, prosperity. How can you prosper if you’re sick? How can you have prosperity if you’re deprived of economic values? How can you have the American Dream? … I was brought to this house and my father built this house before he met my mother. And I think that goes back to what we were talking about environmental justice and the family.… That was a part of the American Dream.

Smith’s discussion of environmental justice leads back to his vision of homeownership. For Smith and other environmental justice activists, achieving environmental justice meant the chance to rebuild their lost American Dream and attain the social opportunities that they had historically been denied.

To achieve this goal, HAPIC leaders decided to focus on relocation rather than cleanup. Ideally, they envisioned the relocation of the community as a whole and sought to create a replica of the old Hyde Park.42 Arthur Smith went on to say,

I’d like to see everybody move. All the streets out here, re-create them somewhere in the city.… And we got the next generation coming up one, two, three. Why not re-create this and then make it the dream I think Mother Utley had for everybody. Make it the dream that Reverend Roundtree had for everybody.43

By relocating as an intact community, Hyde Park residents could set themselves back on the road to the American Dream that they had originally envisioned. Achieving environmental justice then meant reestablishing a place that provided the opportunities required for social mobility along with the warmth and friendship of close-knit community life.

Early on, living in Hyde Park meant that you were someone on the move, someone who had overcome hardship and worked hard to buy property to provide your family with a better way of life. Back then, the opportunity to own land had transformed it from a site of the oppression of slavery and sharecropping to a site of promise. After 1990, however, being a Hyde Park resident meant that your dream was endangered and your family’s health might be threatened. In short, the environment had permeated and despoiled your dreams, and you were trapped in a neighborhood where no one wanted to live.

Environmental psychologists tell us that upon discovering their toxic conditions, these communities undergo “lifescape shifts,” or a process of reinterpreting their health, their past dreams, and their future prospects.44 But in Hyde Park, such shifts did not generate a full-scale paradigm change. Rather, while residents were well aware that their neighborhood was no longer a place of promise and dream fulfillment, they also continued to associate it with a proud, active past throughout which they had fought for their rights as American citizens. When they found out about environmental degradation, then, Hyde Park activists just added clean air, water, and soil to the long list of resources to which they were already fighting for access.45

The ecological circumstances that transformed a social environment of gardens and dream homes into one of toxic contamination and unsellable property were not simply acts of nature; they were the result of a complex combination of economics and politics.46 Environmental justice activists thus teach us that the environment is both social and ecological, and that everyday categories such as “land” and “environment” may seem transparent but mean very different things for different people. In places like Hyde Park, where people have faced the tyranny of slavery, sharecropping, and Jim Crow laws, and where they continue to face various kinds of institutional and individual discrimination, race is the primary lens through which such definitions are perceived. The environment, then, represents both toxic poisons and the social poison of racial discrimination, and seeking environmental justice means overcoming a long and vicious history of racism in America.