“I don’t think I’ve been able to be focused the way that I’ve been when I’m climbing. It totally channels my energy in such a way that I completely lose myself. And that is such a good feeling.”

Chris Sharma

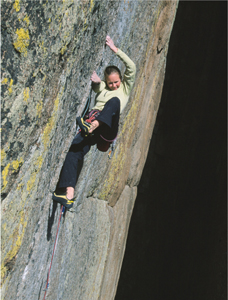

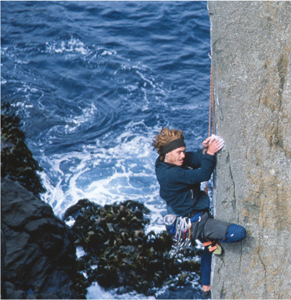

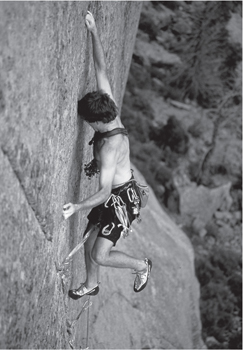

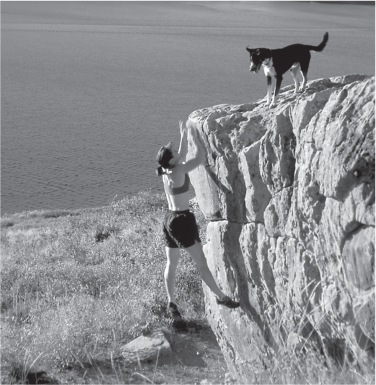

Climbing is a rewarding combination of adventure and gymnastics: finding the best handholds, placing your feet confidently, moving efficiently, using good technique. Climbing challenges you to push the limits of your skill, strength, endurance, and psyche. Climbing with correct technique maximizes efficiency and increases confidence so you can climb harder and use less strength doing it. Think vertical yoga, with the cliff and gravity as the teachers.

How you grasp the handholds or stand on the footholds depends on their size, shape, and orientation. The best way to position your body is determined by the locations of the holds and the steepness of the rock. This chapter covers the most common foot positions, hand grips, and body positions used in rock climbing. These fundamentals are important, but rock climbing is about movement, which is impossible to show with just words and photos.

To improve your climbing movement:

Watch climbing videos.

Watch climbing videos.

Observe good climbers in action.

Observe good climbers in action.

Hire a climbing coach or guide.

Hire a climbing coach or guide.

Train in a climbing gym.

Train in a climbing gym.

Get outside to climb and boulder.

Get outside to climb and boulder.

Rock climbing can be frightening, even when there’s no true danger. That kind of exhilaration is one of the sport’s strange appeals. But it’s hard to climb smoothly and efficiently when you’re scared; fear makes climbers become shaky and flail. So it’s important to sort out and confront some of that fear. There are two kinds of risk: perceived risk and real risk. In climbing it is essential that you learn to tell the difference between the two and act accordingly.

Perceived risk: Learn to suppress your fear when the danger is not real so you can climb more powerfully, maintain mental control, and make safe decisions. Climbers who cannot control perceived risk can potentially make dangerous mistakes while distracted by irrational fear, thus creating real risk.

Real risk: Listen to your fears when danger truly exists and either retreat safely or climb with perfect control. Develop a mental monitor that constantly scans the world around you for real risk. Remember that much real risk is not obvious, and just because other climbers are doing a move or a route doesn’t mean it’s okay for you.

A positive attitude breeds success. Constant doubt—thinking, “The climb’s too steep,” “I’m too short,” or “That climb has a crack, I can’t do it”—is self-defeating. Climbing with confidence is far more productive—and fun. Your mental attitude and confidence are more important than your physical prowess on the rock.

Practicing in a climbing gym builds strength, flexibility, technique, and confidence, but to climb well on real rock, you need to climb on real rock. Holds in climbing gyms are easy to find, generally marked in red, blue, green, and yellow. Holds on real rock are often subtle. Sometimes a foothold is just a patch of rough-textured rock or a tiny edge that requires placing your foot precisely and holding it still as you move onto it. A climbing gym does not train you for these subtleties. Perhaps that’s why we sometimes see huge and ugly chalk tick marks even on obvious outdoor holds, because the climbers who chalked them are accustomed to well-marked gym holds.

Bouldering is excellent practice for improving your climbing. In a single bouldering session you can climb many short boulder routes or problems at or near your limit. Don’t just focus on the hardest boulder problems though. Moderate bouldering helps improve your flow while moving on the rock. Long moderate routes also improve your ability to climb smoothly and efficiently on the rock.

Efficient climbing requires good footwork. Legs and feet are designed to bear body weight; arms are not. As beginners, women tend to climb better than men because women automatically find ways to avoid pulling with their arms, using their legs and feet instead (perfect technique), while men often rely on their natural upper body strength to pull themselves up the rock, neglecting their feet and legs—a recipe for burnout.

To maximize the weight on your feet:

Take the time to find the best footholds.

Take the time to find the best footholds.

Place your feet precisely on the holds.

Place your feet precisely on the holds.

Keep your feet perfectly still as you move your body.

Keep your feet perfectly still as you move your body.

Maintain a body position that keeps your weight over your feet.

Maintain a body position that keeps your weight over your feet.

Make smooth weight transfers using your legs as you climb.

Make smooth weight transfers using your legs as you climb.

Stay relaxed.

Stay relaxed.

When a handhold is beyond reach, you can often solve the problem by moving one of your feet higher. Don’t forget to look to the sides, but the ideal footholds are located in front of your body, at shin to knee level. Keeping your feet under your core puts your body weight onto your feet, where it belongs. Take several small steps when possible, rather than single big steps that require more power; but don’t be afraid of taking a large step to move quickly out of a difficult spot and onto easier terrain.

How you stand on a foothold depends on its shape and orientation as well as the available handholds and desired body position:

As you step from the ground to the rock, improve traction by wiping the dirt and gravel from the bottom of your shoes.

As you step from the ground to the rock, improve traction by wiping the dirt and gravel from the bottom of your shoes.

Because rock shoes are sticky and grip tenaciously, you can stand on tiny edges or rough patches of holdless rock.

Because rock shoes are sticky and grip tenaciously, you can stand on tiny edges or rough patches of holdless rock.

If the footholds are poor, push your feet slightly into the rock to make them stick.

If the footholds are poor, push your feet slightly into the rock to make them stick.

Use the rock geometry in creative ways, not just the holds.

Use the rock geometry in creative ways, not just the holds.

Push your feet outward in opposing directions (stemming) to get weight off your hands.

Push your feet outward in opposing directions (stemming) to get weight off your hands.

On overhanging terrain, pull with your feet (toe hook, heel hook).

On overhanging terrain, pull with your feet (toe hook, heel hook).

Let your inner monkey out—when the climbing is safe, keep moving and experimenting with possible holds rather than obsessing over finding perfect holds.

Let your inner monkey out—when the climbing is safe, keep moving and experimenting with possible holds rather than obsessing over finding perfect holds.

On steep or convoluted terrain, visually locate the next set of footholds before you move up; because once you move up, you may be unable to see them from above. The two foot positions that you’ll use most are edging and smearing. When you have a small-to-medium ledge, standing on the inside edge of your foot is often the most stable and restful foot position. Depending on the shape and size of the hold and personal preference, stand on the ball of your foot or the side of your big toe, with your shoe positioned between parallel and 45 degrees to the wall. Place your foot precisely on the best part of the edge, and keep the foot steady so it can’t slip as you move onto it.

On steep or convoluted terrain, visually locate the next set of footholds before you move up; because once you move up, you may be unable to see them from above. The two foot positions that you’ll use most are edging and smearing. When you have a small-to-medium ledge, standing on the inside edge of your foot is often the most stable and restful foot position. Depending on the shape and size of the hold and personal preference, stand on the ball of your foot or the side of your big toe, with your shoe positioned between parallel and 45 degrees to the wall. Place your foot precisely on the best part of the edge, and keep the foot steady so it can’t slip as you move onto it.

Smearing

As you gain skill and foot strength, using the very tip of your big toe with your foot at 90 degrees to the wall, a bit like a ballerina in toe shoes, is the most powerful and versatile way to stand on a small hold on difficult terrain. This “frontpoint” method has several advantages:

It positions you neutrally, allowing you to more readily turn your body in either direction for the next movement; front-pointed, you’re not stuck with your flank, or foot, leg, and hip, facing in one direction.

It positions you neutrally, allowing you to more readily turn your body in either direction for the next movement; front-pointed, you’re not stuck with your flank, or foot, leg, and hip, facing in one direction.

You can use the smallest holds with precision.

You can use the smallest holds with precision.

You can maximize your reach by extending on tiptoe, just as you do when trying to reach something on a high shelf—standing on the side of your foot can be more comfortable, but shortens your reach.

You can maximize your reach by extending on tiptoe, just as you do when trying to reach something on a high shelf—standing on the side of your foot can be more comfortable, but shortens your reach.

ADVANCED TIP

With a good edge on vertical or slightly overhanging rock, you can pull in with your foot as well as push down. By transferring this pulling force through your leg and body via body tension, you’ll decrease the load on your hands and make them less likely to slip off tiny handholds.

If you’re stepping through horizontally or backstepping, you’ll stand on the outside edge of your foot, just behind your small toe. The outside edge is less intuitive than the inside edge, but outside edging helps position your body to make long reaches and get weight onto your feet on steep rock. The outside edge also works well when stepping past your other foot on a traverse.

Where no edge exists, you may smear a patch of lower-angled or roughly textured rock. Stand on the entire front of your foot to maximize the surface contact area between rubber and rock. Push down with your toes to distribute the pressure across the sole of the shoe. Keep your heels low to reduce the strain on your calf muscles (the sole should be roughly parallel to flat ground or slightly lower).

If the best foothold is off to the side, you can “grab” the hold with your foot. Pull your weight (using your leg muscles) to roll your hips over the foothold. This is often called a rock on.

Sometimes the only good foothold is quite high. Flexibility helps for high-stepping. You will need to move your hips back from the wall and then reach up to the hold with your foot. Now pull with your leg muscles and push off with your lower foot to get up on the foothold.

Don’t move your foot while you’re standing on it. It is tempting to hop your foot, trying to make a hold feel better, but usually this just repositions your foot in a worse orientation and often causes a slip. Instead, practice leaving your foot exactly where and at what angle you placed it the first time. Use your ankle as a hinge so the foot stays still as you move your body.

High step

A subtle weight shift helps when moving your feet up. Imagine standing with your weight distributed almost equally between both feet. To move the right foot, shift your weight slightly left to unweight the right foot. Now move the right foot, and once you have a foothold, shift your weight back to the center so both feet share the weight. Shift your body slightly right to move the left foot, and once it’s set, come back to the center. If your feet are placed too far to the side, it will be difficult to do this.

If the best footholds are wide apart, smear the left foot near the center temporarily to move the right foot up, then move the left foot back to the side. Even pushing on blank rock can help you make this transition.

Toe-in

Toe hook

On pocketed walls you can toe-in, pointing the tips of your toes into small pockets where the inside edge cannot fit. This technique is also useful on severely overhanging climbs.

Heel-hooking and toe-hooking allow you to use your foot like a third hand, to “grab” holds on overhanging rock. Heel hooks are placed high, often above the climber’s head, transferring weight from arms to the leg.

If you have a horizontal crack or pocket that’s slightly smaller than the length of your foot, you can use a foot cam to pull weight onto your leg. Set the sole of your heel against the lower rock surface, and put your toes deeper into the recess against the higher surface. Pull back with your toes to cam the foot in place. Foot cams work great on overhanging rock.

Foot cam

Using footholds in the proper sequence can be critical. Plan the foot moves before you make them. Sometimes you’ll make an “unnecessary” step so one foot ends up on a key foothold, or you might save space on a foothold so you can match feet (place both feet on the same hold). You can also match feet on a hold to change direction of movement and change which leg you step up on.

The weight on your hands and arms increases as the climbing gets steeper and as the footholds get smaller. On low-angled slabs, footwork carries the day and you can grip lightly with your hands, using them only for balance. On vertical rock with good footholds, you can keep most of your weight over your feet. Overhanging rock requires substantial hand and arm strength, core strength, and upper-body fitness; and building power and endurance is an important part of your training program for climbing overhanging rock. Still, on any angle of rock, you can transfer much of the weight to your legs using good footwork, body position, and body tension.

New climbers—and experienced climbers when they’re scared—have a tendency to overgrip. Gripping too hard quickly brings on overworked, swollen arms: a vicious pump from which it can be difficult to recover. Once your strength is drained, your technique falls apart, along with your confidence. Use the lightest possible grip to make the moves.

When choosing a handhold, you may have a choice between pulling down, pulling sideways (a sidepull), or pulling up (an undercling). Pulling down is intuitive; it’s like climbing a ladder. If you have plenty of holds to choose from and no long reaches, pulling down on your handholds is often the best choice.

Sometimes a hold will be oriented for a sideways or upward pull, and you won’t have any choice about how to use it. Other times you’ll choose a sidepull or undercling to increase your reach and help you reach a faraway hold. Sidepulls can also help you keep a sideways orientation, with your flank to the rock, which helps keep weight on your feet. With experience, you’ll learn when it’s best to pull down, sideways, or up if given the choice.

Keep your arms straight as much as possible so you’re hanging from bone rather than your rapidly depleting biceps. Of course, you have to bend your elbows sometimes when cranking the moves.

Avoid overextending to reach for a distant handhold. It’s tough to pull on a hold that’s at the limit of your reach, and if you lean in too far to the rock to grab the hold, flattening your body against the rock, your feet may slip out from under you. Rather than overextending your reach, move your feet up first.

The key to using your hands is to hold on using the least amount of strength. Good technique and gymnastic chalk both help with this. On all types of handholds, consciously ease your grip to relax into the rock’s natural friction. Here are the basic types of handholds and the techniques for using each one:

Jug: The biggest holds on a climb, like a jug handle.

Feel around to find the best part of a jug where you can relax (don’t overgrip) and recover some strength.

Feel around to find the best part of a jug where you can relax (don’t overgrip) and recover some strength.

Relax your hand and body so you’re hanging on your skeleton and not your muscles.

Relax your hand and body so you’re hanging on your skeleton and not your muscles.

Crimp: The smaller holds, usually in the form of small edges.

Put all your fingertips (or all that will fit) on the best part of the edge.

Put all your fingertips (or all that will fit) on the best part of the edge.

Feel around to find the best “fit” for your fingers and hand, then wrap your thumb over your index finger. The thumb adds impressive strength to your grip because it’s the strongest digit.

Feel around to find the best “fit” for your fingers and hand, then wrap your thumb over your index finger. The thumb adds impressive strength to your grip because it’s the strongest digit.

Crimping can be dangerous for your fingers. If you crimp too hard before you develop enough tendon strength, it is easy to injure a finger tendon. Go easy.

Crimping can be dangerous for your fingers. If you crimp too hard before you develop enough tendon strength, it is easy to injure a finger tendon. Go easy.

Consider using an open grip instead of a crimp when possible—it uses less strength and puts your hand in a less injury-prone position.

Consider using an open grip instead of a crimp when possible—it uses less strength and puts your hand in a less injury-prone position.

Open grip: Holding on with an almost fully open hand.

The open grip is the only way to stick to many sloping handholds.

The open grip is the only way to stick to many sloping handholds.

Crimp

Open grip

The open grip is not as powerful as crimping and more subtle, so you need to train if you want to use it occasionally to avoid crimping on small holds.

The open grip is not as powerful as crimping and more subtle, so you need to train if you want to use it occasionally to avoid crimping on small holds.

The open grip often relies on skin-to-rock friction.

The open grip often relies on skin-to-rock friction.

The open grip works best in cool, crisp conditions.

The open grip works best in cool, crisp conditions.

Don’t always use all of the hold. Instead, align the edge of the hold with one of your finger joints, and press the natural folds in your fingers and hand precisely against the subtle changes in the rock’s angle.

Don’t always use all of the hold. Instead, align the edge of the hold with one of your finger joints, and press the natural folds in your fingers and hand precisely against the subtle changes in the rock’s angle.

Pinch grip: Squeezing a fin or knob of protruding rock as if you’re crushing a can.

Feel around to find places where your fingers can cling to small features.

Feel around to find places where your fingers can cling to small features.

Pinch the rock by opposing your thumb against all your fingers.

Pinch the rock by opposing your thumb against all your fingers.

Finger pinch

Two-finger pocket

Mono

For small pinches, squeeze the rock using your thumb and the outside edge of your index finger.

For small pinches, squeeze the rock using your thumb and the outside edge of your index finger.

Pocket: Some rock types are peppered with solution pockets (small holes in the rock).

Since a pocket offers 360 degrees of possible edges, the bottom is not always the best hold. Take the time to find the best “lip” to pull on.

Since a pocket offers 360 degrees of possible edges, the bottom is not always the best hold. Take the time to find the best “lip” to pull on.

If you have choices in which footholds to use, choose footholds that position your body most comfortably and powerfully on the pocket.

If you have choices in which footholds to use, choose footholds that position your body most comfortably and powerfully on the pocket.

Whenever possible, use a pocket with an open grip and align your finger joints with the lip of the pocket rather than burying your hand as deep as possible.

Whenever possible, use a pocket with an open grip and align your finger joints with the lip of the pocket rather than burying your hand as deep as possible.

On pockets that fit only one finger, monos, be careful to keep weight on your feet and not pull too hard to avoid injuring a finger.

On pockets that fit only one finger, monos, be careful to keep weight on your feet and not pull too hard to avoid injuring a finger.

On two-finger pockets, try the middle and ring finger, though sometimes the middle and index finger will fit better.

On two-finger pockets, try the middle and ring finger, though sometimes the middle and index finger will fit better.

Remember where the pockets are because you’ll likely want to use them as footholds later, and they may be difficult to see from above.

Remember where the pockets are because you’ll likely want to use them as footholds later, and they may be difficult to see from above.

Sidepull: A vertically oriented hold that’s off to the side of your body.

Lean away from the sidepull and pull to the side to make the grip work, because you can’t pull down on a vertically oriented edge.

Lean away from the sidepull and pull to the side to make the grip work, because you can’t pull down on a vertically oriented edge.

If the hold is on the right, lean left so your body weight opposes the hold.

If the hold is on the right, lean left so your body weight opposes the hold.

Whichever direction you are sidepulling, position your feet to push in opposition.

Whichever direction you are sidepulling, position your feet to push in opposition.

Gaston: The opposite of a sidepull—pushing outward on a hold relative to your body.

Gaston

Usually you’ll crimp the hold and pull outward, with your elbow pointing away from your body like you’re trying to open an elevator door.

Usually you’ll crimp the hold and pull outward, with your elbow pointing away from your body like you’re trying to open an elevator door.

The Gaston is named for the pioneering French climber Gaston Rébuffat, who ascended cracks by pushing outward on their edges rather than jamming. A much better way to climb cracks is covered in the next chapter.

The Gaston is named for the pioneering French climber Gaston Rébuffat, who ascended cracks by pushing outward on their edges rather than jamming. A much better way to climb cracks is covered in the next chapter.

Using a Gaston effectively requires experience to place your feet properly relative to the handhold. Bouldering is one of the best ways to learn to use the Gaston.

Using a Gaston effectively requires experience to place your feet properly relative to the handhold. Bouldering is one of the best ways to learn to use the Gaston.

Palm: Using the palm of your hand rather than your fingers.

Palm both sides of a corner to oppose your hands against each other, or you can palm one hand and oppose one or both feet on the other side of the corner.

Palm both sides of a corner to oppose your hands against each other, or you can palm one hand and oppose one or both feet on the other side of the corner.

Palming

Practice using your palms frequently on easier terrain, so you will feel comfortable using this insecure but effective technique on harder climbing.

Practice using your palms frequently on easier terrain, so you will feel comfortable using this insecure but effective technique on harder climbing.

Sometimes you can palm a coarse patch of rock above you, almost like an open grip, and pull down on it.

Sometimes you can palm a coarse patch of rock above you, almost like an open grip, and pull down on it.

The angle of the rock and the location of the handholds and footholds determine the optimal body position. The idea is to adapt to the rock.

Good body position helps you:

Minimize the weight on your arms.

Minimize the weight on your arms.

Extend your reach to grab faraway handholds.

Extend your reach to grab faraway handholds.

Pull on holds that face the “wrong” way.

Pull on holds that face the “wrong” way.

Gain a stable stance from which to rest or place protection.

Gain a stable stance from which to rest or place protection.

There are three basic types of face climbing, described based on the rock angle: slabs, vertical rock, and overhanging rock. Climbers tend to enjoy, and focus on, one type more than the others, but many individual routes or climbs cover all three types of terrain. Practicing on the terrain you are less comfortable with will make you a much better climber than always staying in your comfort zone.

A slab is a rock face that is less than vertical. Slab climbing requires balance, smooth movement, and trust in your feet, because there’s often little for your hands to grip. Because climbing gyms are usually steep and even the smallest artificial holds are large compared to the small holds on real rock, learning slab-climbing skills requires intentionally practicing on slabs out-of-doors. Here are some pointers for climbing slabs:

Leaning forward is a common error made on slabs. If you lean too far forward, lying almost flat on the slab, your feet will slip out from under you. Push your hips out and away from the rock to keep your weight directly over your feet.

Leaning forward is a common error made on slabs. If you lean too far forward, lying almost flat on the slab, your feet will slip out from under you. Push your hips out and away from the rock to keep your weight directly over your feet.

Focus 95 percent of your attention on your feet, and choose handholds that help you transition your weight onto the next foothold.

Focus 95 percent of your attention on your feet, and choose handholds that help you transition your weight onto the next foothold.

Usually on slabs, you’ll maintain a frontal body position, with your body facing the rock; but sometimes shifting your hips sideways to the rock can save the day.

Usually on slabs, you’ll maintain a frontal body position, with your body facing the rock; but sometimes shifting your hips sideways to the rock can save the day.

ADVANCED TIP

Body tension can help on a slab when the footholds are poor. By pushing your feet into the rock through tension in your core, you can stand on bad or nonexistent footholds. Because every action has an equal and opposite reaction, any weight applied to your footholds must be countered by weight pulling out on your handholds. Making good use of body tension is a fairly advanced skill; fortunately, it’s rarely important on easier climbs.

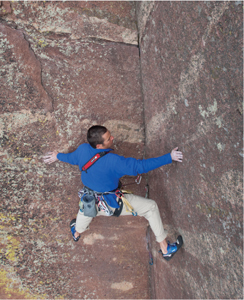

Climbing vertical rock is some of the more dance-like of climbing’s wide range of techniques. Because the rock is oriented almost perfectly in line with gravity, the smallest changes in your body position make a big difference in how easily you can move. Focus on the orientation of your hips, the direction your feet are pointing, and stemming technique.

Beginners often make the mistake of keeping their bodies facing forward and their hips oriented parallel to the wall at all times. The holds and your personal climbing style will determine which hip orientation is best, but most good climbers when on vertical terrain will spend much of the time sideways to the rock, flank to the wall and hips oriented perpendicular to the rock.

To learn to climb with your hips perpendicular to the rock:

Point your feet and knees in the same direction, so you’re standing on the outside edge of one foot and the inside edge of the other.

Point your feet and knees in the same direction, so you’re standing on the outside edge of one foot and the inside edge of the other.

Standing on the outside edge of one foot, or backstepping, allows you to use footholds on either side of your body with either foot.

Standing on the outside edge of one foot, or backstepping, allows you to use footholds on either side of your body with either foot.

Look for sidepulls; these more vertically oriented handholds often allow you to reach much farther than horizontal holds.

Look for sidepulls; these more vertically oriented handholds often allow you to reach much farther than horizontal holds.

If the hand- and footholds are aligned so your body tends to rotate awkwardly, you can flag one leg out to the side to counter the rotation. To do this, use your leg like a monkey uses the counterweight of its tail, and consider swinging it in any direction and placing it against even blank rock to keep your body in the ideal orientation.

If the hand- and footholds are aligned so your body tends to rotate awkwardly, you can flag one leg out to the side to counter the rotation. To do this, use your leg like a monkey uses the counterweight of its tail, and consider swinging it in any direction and placing it against even blank rock to keep your body in the ideal orientation.

Backstepping

Stemming

When climbing in a corner, stemming—where you oppose your feet against each other across the corner—allows you to get weight off your arms, even on steep terrain. Stemming can provide a great rest or allow you to climb where the holds are slim by using opposing pressure against two rock walls. Try palming the rock in conjunction with stemming. Good climbers stem frequently even when not in a corner, by using footholds that may require a stretch of the legs but face somewhat toward each other.

Overhanging rock is strenuous and often technical. Climbing steep rock requires fitness, tenacity, and imagination. On overhanging rock:

Think fast and commit to the moves before your arms melt.

Think fast and commit to the moves before your arms melt.

Rest when possible, even if you don’t really need to rest.

Rest when possible, even if you don’t really need to rest.

A variety of contortionist positions help climbers rest and maximize the weight on their feet on overhanging rock.

A variety of contortionist positions help climbers rest and maximize the weight on their feet on overhanging rock.

Keep your arms straight whenever possible, even while moving, to save energy.

Keep your arms straight whenever possible, even while moving, to save energy.

The backstep combined with the twistlock minimizes the effort required to move on steep rock. For example, while grabbing a handhold near chest level with your left hand, backstep and turn your right hip into the wall, so your arm folds tightly across your chest. The twistlock minimizes the leverage on your arm by keeping it near your body.

Another useful technique on overhanging rock is the drop knee, where you edge the outside of your foot on a hold, turn your hip into the wall as in backstepping, and twist your knee so it’s almost pointing down (but be careful not to overstrain the knee joint). This pulls your hips in so they’re nearly over your feet. The other leg, which should be kept straight if possible, is planted on a good foothold and bears much of your body weight. The legs work together during the drop knee by opposing each other, as in a stem.

Drop knee

On steep rock, body tension—keeping your torso rigid by using your core strength—enables you to make the handholds and footholds work together. Allowing your body to slump and your core to relax on overhanging rock puts most of your weight on your arms and may cause your feet to pop off the footholds. Using body tension, which originates from your abdomen and back muscles, you can transfer weight to your feet and keep them on the rock. Body tension also allows you to use holds creatively—for example, using two sidepulls in opposition creates a combined hold that works where neither hold would work alone.

All the fancy footwork, huge arms, and perfect body position in the world won’t help you climb if you don’t know how to move. That’s why this book can only take you so far: We can explain the footwork and handholds and illustrate them with photos, but we can’t show you how to move. Moving on easy rock is akin to climbing a ladder, but as the climbing gets more difficult, the moves become a combination of gymnastics, vertical dance, and full-on monkey maneuvers.

All climbers eventually develop their own style for moving over rock. The style often depends on experience, body type, strengths, old injuries, kinesthetic awareness, and mentors’ style. Old-school climbing favored slow, static, pretty-as-a-swan moves. This style of climbing works fine on moderate routes and it’s preferable on hard-to-protect routes; casually tossing for unknown holds is dangerous when the consequences of falling are bad. For today’s harder routes, it’s all about the movement, and a dynamic style of moving is often the most efficient.

In the early 1960s, John Gill invented hard bouldering and brought gymnastic movement to climbing. Gill wasn’t fascinated by hand, foot, or body positions; he was drawn to climbing movement. He trained fiendishly to enable his body to make visionary moves on his climbs, and he made a bigger leap in climbing standards than any climber before or since. He was doing the equivalent of 5.14 gymnastics over 20 years before 5.14 became established as a climbing grade. If you watch the best climbers of today, it’s not just their amazing grip strength or flawless body positions that bring them success; it’s the way they move.

A static climbing style suits beginners well because complicated gymnastic movement is unnecessary on easy or moderate terrain. One thing to avoid, though, is “doing pull-ups” to make upward progress. As we’ve already said, let your legs do the work. The leg crank is a standard move that we do every time we walk up and down a flight of stairs—we put our foot on the higher step and use our leg strength to raise our body onto that step. If you make a little bounce off the lower foot to get your momentum started, which we call the bounce step, you can make the step with less effort. Try it on a set of stairs. Walk up a flight of steps statically, fully cranking all your weight with only the upper leg. Now try the same thing, but bounce slightly off your lower foot to get your weight moving. It’s much easier when you use the bounce step.

Another technique for moving up is the frog move: With your hands on holds, move one foot up, then the other, before cranking your body weight up using both legs. This requires less power than cranking all your weight up on one leg.

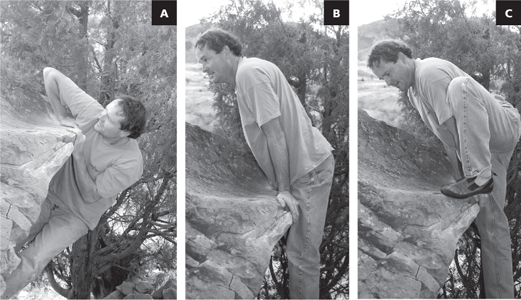

A mantel move is often the solution when you have a flat ledge with no more reachable holds above (or when you’re topping out on a boulder or big ledge). Many variations exist.

Frog move

Mantel

To crank a mantel:

1.Place one hand onto the ledge, then the other.

2.Pull with your arms, push with your legs, and walk your feet up until the ledge is at about chest level.

3.Flip one elbow up so it points straight up (A), while your hand palms the top edge of the ledge; follow suit with the other elbow and hand.

4.Push down with both arms while walking your feet up until both arms are straight as they push down on the ledge (B).

5.Bring one foot up onto the ledge and stand up to finish (C).

Turning the lip of a roof can often be difficult because the footholds are in awkward places. Each roof presents its own challenges.

Here is a general set of roof moves:

1.Work your hands over the lip of the roof while using the best footholds under the roof.

2.Move your hands farther above the lip if possible, onto the best handholds.

3.Try to find a hold to hook your heel on, to pull weight onto your leg.

4.Move your hands up farther while pulling on your heel hook, and then get your knee up and edge the foothold.

5.Rock weight onto your foot while pulling with your arms. Stand up, using your leg strength and balance.

Instep rest

Finding creative rests on strenuous climbs can make the difference between recovering and moving through, or pumping out and falling off. Rest whenever possible, and climb through when no rests are available. The instep rest gives your foot a break if you have a large edge to stand on. Stand with your leg straight and bear all your weight on the instep or heel so you can relax your foot and leg muscles. If you can’t get weight off your hands, try to shake out your arms one at a time. Find a bucket or a jug to grab onto, lift one arm, and shake your hand to get the old blood flowing out of it. Now drop the hand and shake it to get fresh blood in. Switch hands and repeat. It may take several iterations of shaking out to feel somewhat recovered.

Sticking a dyno

Momentum is a huge part of climbing, and dynamic moves, like the bounce step above, are important to master. If you move steadily upward with confidence, the climb will go easier. Once you bog down, lose confidence, and start to hesitate, the climbing becomes much more difficult. Dynamic climbing is another way of using momentum to save energy on steep climbs and allow passage between distant handholds. How much momentum you need depends on your strength and the moves you choose.

Sometimes the holds are so small that you can’t hang on with one hand while moving the other. In this case, the fast grab may get you to the next hold. With a small thrust from your legs and arms, quickly and precisely slap your hand to the next hold. The hold better be good enough to grasp and you’d better hit it spot-on, because if you can’t hold it, you’ll fall.

This is one potential disadvantage of dynamic moves: You may have to commit to a hold before you know how good it is. If you climb statically, you can reach the hold, feel around on it, find the best hand position, and try another hold if it’s not good enough. But if you lunge for a hold and it’s not good enough, you’re outta there.

If the hold is too far away to reach statically, a dyno may be in order. Eye the hold you want to hit and focus on it. Sink down on your legs to set up for the dyno, then push with your legs and pull with your arms to get your body moving toward the hold. Most of the thrust comes from your legs. As your body reaches its apex, move your hand quickly to the hold and latch it. It’s best to hit the hold at the deadpoint—the top of your arc, when your body is essentially weightless. If you overshoot the hold, you’ll have to catch more weight as your body falls back down onto it.

A dyno is much easier if you can keep your feet on the original footholds. If the handhold you’re shooting for is beyond reach from the footholds, you’ll have to jump to make the reach. In this case, your hands must catch all your weight when you latch the handhold. Concentrate on grabbing the hold with authority, fully prepared to catch your weight, to stick the dyno.

Double dyno

On occasion, dynamic moves may require a double dyno, where you fly with both hands simultaneously reaching to the next handholds. Here you’ll need powerful thrust from your legs, a perfect trajectory toward the handholds, and a good, strong latch when you grab them.

Find an easy low-angle boulder with small footholds. Put a crash pad at its base or set a top-rope.

Climb up and down the face. Place your feet precisely on the best part of the holds, holding them steady as you move. Keep most of your weight on your feet and use your hands only for balance. Notice the weight shift as you lean slightly left to move the right foot up, and slightly right to move the left foot.

Climb up and down the face. Place your feet precisely on the best part of the holds, holding them steady as you move. Keep most of your weight on your feet and use your hands only for balance. Notice the weight shift as you lean slightly left to move the right foot up, and slightly right to move the left foot.

Climb the same face using only your right hand for balance. Keep your center of gravity directly over your feet. Repeat with the left hand. Try making the steps completely static, and also try bouncing off your lower foot. Notice how the bounce gives you some momentum to propel you through the move.

Climb the same face using only your right hand for balance. Keep your center of gravity directly over your feet. Repeat with the left hand. Try making the steps completely static, and also try bouncing off your lower foot. Notice how the bounce gives you some momentum to propel you through the move.

Now climb the face with no hands. This teaches you how much you can trust your feet and improves your balance. If your feet slip, try maintaining more downward pressure on your toes. Practice until you can smoothly climb the face without hands.

Now climb the face with no hands. This teaches you how much you can trust your feet and improves your balance. If your feet slip, try maintaining more downward pressure on your toes. Practice until you can smoothly climb the face without hands.

Find a steeper face with small edges. With both feet on the starting footholds, eye a small edge up and to the side. Bring your foot to the best part of the hold and hit it dead-on. Now smoothly transfer your weight onto the new foothold. Practice until you can consistently hit the foothold on the first try and smoothly transfer your weight between the holds.

Find a steeper face with small edges. With both feet on the starting footholds, eye a small edge up and to the side. Bring your foot to the best part of the hold and hit it dead-on. Now smoothly transfer your weight onto the new foothold. Practice until you can consistently hit the foothold on the first try and smoothly transfer your weight between the holds.

Climb without looking up for the handholds. Instead, focus completely on your feet. Strive to stay balanced and press your weight up with your legs.

Climb without looking up for the handholds. Instead, focus completely on your feet. Strive to stay balanced and press your weight up with your legs.