3

CAPTURING SCENT

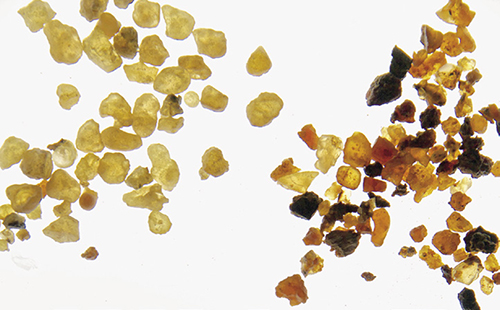

Resins, from the hardened sap of shrubs and trees, include frankincense (left) and myrrh.

Botanical fragrance has been treasured for centuries. The ancient Egyptians grew aromatic plants and placed leaves, flowers, and branches in the tombs of their pharaohs to perfume the afterlife. Many Roman and Greek homes, whether they belonged to wealthy city dwellers or humble farmers, were built around planted courtyards. The openings of the houses faced inward so that the plants’ perfumes, thought to have healthful effects, filled the house.

The word “perfume” comes from the Latin per fumare, which means “to pass through smoke.” The earliest perfumes might have been incense. Early incense was plant-derived, made from dried amber-like resins such as frankincense and myrrh, members of the Burseraceae family of trees and shrubs distinguished by terpenes, a large class of aromatic hydrocarbons.

In medieval monasteries, monks used fragrant herbs to aid recuperating infirmary patients. Tussie-mussies, small bouquets of fresh flowers that ladies carried to mask the smells of the street, have been around for centuries. These were made with plants like violets, lily of the valley, scented geraniums, and Rosa centifolia (the cabbage rose).

Today, plants continue to inspire perfumes, and, in many cases, expensive fine fragrances are made with molecular compounds harvested from flowers, leafy herbs, fruits, seeds, twigs, roots, rhizomes, bark, sap, and resins—precious ingredients. One thirty-milliliter bottle (approximately 1.01 ounces) of Chanel Nº5, the French fashion house’s signature scent, uses one thousand jasmine flowers plus twelve full-size blossoms of R. centifolia.

I was surprised how the fragrance of a spritz of such a perfume changed over time, from the first half hour to the next couple of hours, and on through the rest of the day. Fine fragrances are multilayered, and the passage of time adds to their complexity. Perfumers refer to “strength,” “carry,” and “trail of scent.” We might say a scent has a “note,” meaning a hint of one thing or another. But in perfumes, notes are very specific things related to time as well as scent.

A scent evolves from first blush to “dry down,” hours later. There is a three-note sequence that creates what is called a perfume’s “fragrant accord.” The top note, also referred to as the opening or head note, is the perfume’s first impression. This is generally the lightest scent, which you encounter when you open a bottle, and it is the first to fade once the perfume is applied—usually within a half hour. These notes are often fresh, strident smells, perhaps something like ginger or lime. Next are the middle or heart notes, which come forward as the early scents recede. These might be jasmine, ylang-ylang (pronounced EE-lang EE-lang), or orange blossom. The base notes—the woody smell of vetiver, rich balsamic vanilla, or sexy animalic musk—are the last to die away. The base notes mingle with the heart notes to create the body of a perfume and linger together for hours.

A medieval cloister garden often had a central water feature, surrounded by fragrant healing herbs, as shown here at the Met Cloisters in New York City.

The blossoms of citrus species (here, Citrus medica) have their own unique fragrances. Seville or bitter orange flowers, C. aurantium var. amara, offer a rich floral, green smell, with jasmine, honey, and fruit scent, for perfumes.

The Buddha’s hand (Citrus medica var. sarcodactylis) is all rind and no pulp and is named for its resemblance to the stylized hands of statues of Buddhism’s founder. The fruit’s warm, sweet floral fragrance can fill a room.

A display of homegrown citrus fruits in landscape designer Cevan Forristt’s garden in San Jose, California.

In Ancient Egypt, fragrant plants or ground and mashed flowers, seeds, roots, and chunks of resin were steeped in wine or palm oil, and the mixture was poured into cloth bags that were wrung and pressed by two people using staffs.

Which notes are the first to dissipate or the last to linger is not a product of the imagination; the smells’ molecules may actually have different weights. And the chemicals combined to make up these notes do not have just a few components, of course; they may have dozens or hundreds of ingredients.

SCENT-CAPTURING TACTICS

Your reaction to wonderful flower smells can be profound. Take in a good smell; you’re in for intense sensory gratification. Pleasant smells can alter your physical state. Tom Putvinski, a hybridizer of clove-scented deciduous azaleas, says, “Fragrance bypasses the intellectual part of the brain and speaks directly to the emotions.” Face it: Good smells make us happy.

Finding ways to capture and store plant essences so that we can keep enjoying the pleasure they bring has been a goal for nearly as long as fresh flowers have been used to scent the home (or the body). The simplest way to share botanical fragrance is to bring cut flowers into the house. People who grow food have many options for preserving, from canning to freezing. Herb plant stems and leaves can be hung up to dry, and many will retain their flavor. A few flowers, too, smell after being dried, including lavender and even some roses.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, the French word potpourri, whose literal meaning is “pot of decay,” began to be used to describe an early air freshener: Bowls of dried fragrant flowers, herbs, and spices were placed in rooms to mask unpleasant odors. But most contemporary versions of potpourri are like smelly granola, and often depend on the addition of real or synthetic scented oils to enhance their aromas; I rarely find them realistic or agreeable.

We know that most flavors are soluble in water. Similarly, plant fragrances can be absorbed by oils and fats. Temple and tomb paintings depict ancient Egyptian ladies wearing on their heads unguent cones, made of beeswax or tallow impregnated with fragrant leaves and flower petals; as the cone melted, the lotion would run down and scent their hair and faces.

The Greeks and Romans not only traded plant parts but also prepared aromatic oils in the way, today, we might flavor vinegar with herbs. Concentrated infusions may have come from steeping flowers, leaves, seeds, twigs, bark, fruits, tree secretions, and roots over heat. Once it cooled, the scented oil was poured off, ready for use as perfume; it might be stored in alabaster urns for future use.

Essential oils are aromatic liquids in plants obtained through steam distillation, which has been practiced for millennia to capture plant fragrances. Five thousand years ago, the Mesopotamians used earthenware apparatus for this purpose. By the tenth century, Persian chemists were distilling scents such as rose oil, also called rose attar, from fresh flowers. Modern steam distillation involves laying plant parts on a perforated rack inside a vat, above gently boiling water. The vat has a special lid that allows the vapor to flow through a cooled tube, condense and drip into a new container. The essential oil floats on the surface of the distilled water, to be siphoned off. The remaining water is called the “hydrosol” or “hydrolat” and can be used for aromatherapy. The hydrosol left over when the Persians made rose oil was the famous rosewater, used for flavoring.

OTHER PREPARATION METHODS

There are ways to obtain fragrance from flowers and plants besides burning, infusing, or distillation. Maceration consists of steeping flowers in a bath of hot grease, letting them infuse, and renewing them until the grease (called the pomade) is completely saturated.

A decoction is like an infusion, but the liquid is heated and reheated to extract harder-to-process ingredients such as bark, berries, or roots. Most commercial infusions use warmed chemical solvents like alcohol to extract the essential oil.

Expression, or “cold pressing,” involves squeezing natural oils out of things like orange rind. Small pieces are cut up, mixed with some water, and pressed in a machine. In industrial applications, the oil is separated in a centrifuge.

The heat of distillation is good for rugged plants like lavender, but delicate flowers such as jasmine and mimosa have to be treated with chemical solvents. Flowers can be exposed to an organic solvent such as hexane. This yields a waxy substance called a “concrete.” The concrete is then mixed with ethyl alcohol, which separates the wax from the plant oils. The alcohol evaporates, leaving what is called the “absolute.” This highly concentrated product is used in perfume.

Carbon dioxide extraction is an environmentally friendly method because no harsh chemicals are used. Pressurized liquid or gaseous carbon dioxide also has the advantage of working at lower temperatures and, therefore, not “cooking” and changing the essential oils.

Lavenders (clockwise from farthest left): Lavandula ‘Compact White’; fern-leaf L. multifida; L. × intermedia ‘Grosso’; L. × intermedia ‘White Dwarf’; L. × intermedia ‘Lullingstone Castle’; fringed L. ‘French Variegated’; L. angustifolia ‘Hidcote’ (horizontal); L. ‘Silver Sands’.

A familiar way to capture scent is by bringing cut flowers into the home, such as this arrangement of peony flowers in a Japanesque vase with the leafy stems of yellow-green Spiraea thunbergii ‘Ogon’.

In the enfleurage process, fresh flowers or petals are spread over clarified animal or vegetable fat, which absorbs their fragrance. The blossoms are removed and replaced repeatedly, yielding a highly scented product.

The petals I used came from the small centifolia or cabbage rose ‘Petite de Hollande’, admired since the 1790s for its intense old-rose, powder, and spice fragrance.

PRESERVING WITH ENFLEURAGE

How can we preserve fragrance without building a laboratory in the basement? There is an age-old method, the principle of which can be applied today when dealing with especially delicate floral sources. It is best known by the word “enfleurage.”

Old accounts of this process called for clarified lard or tallow to be spread in a thin layer on a pane of glass mounted in a wooden frame or sash. Fresh flowers were strewn over the grease, and the frame was placed in a cool, dark place. After about twenty-four hours, the flowers were lifted off the grease and replaced. This procedure could be repeated for up to three weeks. Ultimately, the flower-scented fat was scraped off the glass for processing.

Enfleurage can be practiced with flowers, like jasmine and tuberose, that continue developing and giving off their aromas after harvesting but do not stand up to heat. The result is a fresh, clear scent.

Once the fat is saturated with fragrance, it is called the “enfleurage pomade.” In the past, the pomade would be sold as a moisturizing cream. But it may also have been soaked in ethyl alcohol, which dissolved the fragrant molecules and separated them from the fat. The alcohol was poured off and allowed to evaporate, and what was left was another version of an absolute.

I tried my hand at making my own enfleurage, using my favorite dwarf antique cabbage rose, Rosa × centifolia ‘Petite de Hollande’. I melted vegetable shortening on a jelly-roll pan in the oven and allowed it to congeal into a quarter-inch-thick layer. Then I pulled petals from fresh blossoms and laid them on the shortening. I covered the surface with petals, lightly pressed them into the fat, and covered the pan with a slightly larger one. I placed the pans in a cool spot away from sunlight for twenty-four hours, after which I removed the petals. I scraped the shortening off the tray, and voilà! It smelled just like my favorite rose. Come January, it was a dream come true to have this precious rose smell while the snow fell outside.

(I imagine that, if using flowers that were not as strongly scented as the old roses, I would have had to repeat the process as long as blossoms were available.)

One way to capture scent is by collecting and drying the aromatic petals of a rose like ‘Soeur Emmanuelle’, with its anise and lavender fragrance.

Roses, lavender, scented geranium leaves, silvery artemisia, and lemon balm are fragrant plants to collect.