REUNION

The great fiftieth reunion of the blue and the gray was being held in July 1911 in Manassas, Virginia, half a century after the first Battle of Bull Run, and the president of the United States was running late. In a gesture signifying that much had changed since the two sides had clashed so long ago, that the age of the horse was ending and the wagon and locomotive too, William Howard Taft decided to drive from the White House to the Virginia countryside in his flashy new motor car, a sporty White steamer.

He brought with him his trusted assistant, Maj. Archibald Willingham Butt. A son of the South born just five months after the Civil War ended, Butt restlessly sought new adventures. He had enlisted in the Army and saw action in the Philippines and Cuba. He never married, giving his all to his career. Eventually he was appointed a White House military adjutant and worked closely with Taft in the White House.

But the art of politics and statecraft bored Butt. He was a man who thrived on danger. A year after this “Peace Jubilee” in Manassas, he would take a rare vacation to Europe. Sailing home in April 1912, his ocean liner struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic. Ever the soldier, Butt was seen by survivors on the deck fighting with men trying to sneak onto the precious few lifeboats. Some accounts have him with drawn pistol, firing at passengers frantic to push their way onto too few rafts. For Butt, it was always chivalry, and always women and children first. He went down with the USS Titanic.

Major Butt did indeed nurture a flair for the theatric. The afternoon drive with the president to Manassas became an adventure as well. They almost never made it.

Along the way, Butt wrote to his sister Clara a few days later, “we met with every obstacle which nature could provide.” They started out at half past noon, four vehicles in a sort of miniature presidential motorcade. They reached Falls Church, Virginia, and stopped for a reception with some fifty attendees. The president drank lemonade and offered a few short remarks. They then drove to Fairfax City and the lawn of the Fairfax County Courthouse. The mayor and other dignitaries met them, but storm clouds suddenly opened up and everyone hurried inside. “It seemed as if the bottom had fallen out of the sky,” Butt wrote.

They pushed on, braving the driving rain, and reached a state senator’s home for lunch. A big man, President Taft was not going to miss his meal. It was the perfect Southern feast: fried chicken, Virginia ham, and hot crisp corn bread. When they had eaten, the sun reappeared. The clock said a quarter to three, and they were due in Manassas in an hour and fifteen minutes. So they drove on, turning onto the Manassas Pike, where they “were bumped and jolted over the worst road I have ever seen,” Butt recalled. They climbed a small hill and spotted a stream below, the water rising. The current was strong and wheel-high. Cross it, or not? Butt hopped out, pulled off his boots, and waded in, testing its depth, searching for a shallow lane. At some points the water reached his armpits, but he found a passable route, and the White steamer huffed through the muck, mire, and the roiling water.

Two miles on they reached Little Rocky Creek, swollen the size of a torrent. Several farmers warned them not to chance crossing it. The president called on the major to wade into this one as well. Off again went the boots, and in he plowed. Too deep, too dangerous, he called out. So they circled back, crossed the first stream again, found an alternate route ten miles out and headed for Centreville. Butt hung his wet socks over the dashboard to dry. No rain had fallen here, but heavy swirling dust picked up and coated the entourage. Still they persisted, finally reaching Manassas at a quarter to six, nearly two hours late. Tired, sweating, dirty, worn, and thirsty—and likely hungry again—the president stepped out of his car and into the crowd.

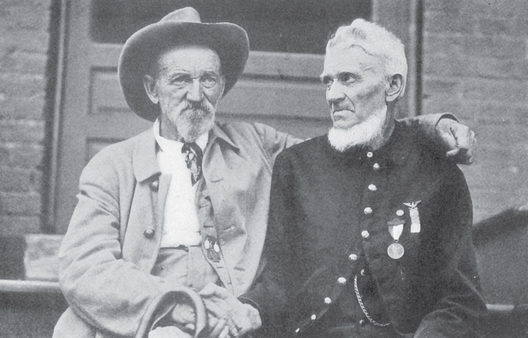

The throng was ten thousand strong, a sight like none of them had seen before. Here the skies were clear and the air steaming, a blistering 90-plus degrees. Red dust kicked up around town. But the air of peace was afloat. Teenage girls waving small American flags wore white gowns and banners, each representing one of the reunited states. The town’s business district near Grant and Lee avenues was decorated with patriotic bunting, and much of it proclaimed “The New America.” A huge banner heralded Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s famous words, “Let us have peace.” Alongside it was a saying from Gen. Robert E. Lee, “Duty is the sublimest word in the English language.” Hotels were jammed, and other guests took rooms in private homes. More guests crowded into two large dormitories at Eastern College, opened just a year earlier. The nearby Prince William County Courthouse, a red brick Romanesque Revival structure also still fairly new, seemed to pitch and sway as the crowd pushed closer and the president climbed to the dais. Peering into the vast audience, he could make out a good number of the 350 faces that had fought a half century ago for the South, and half that many for the North. Many came dressed sharply in old battle uniforms, some with medals pinned to their chests. They were stern, disciplined old men, but hard of hearing. The president would make just a brief address, and he would have to speak loud. But the veterans heard him. Major Butt knew that. Even at a distance, he could see the tears in their eyes.

The president did not need to remind these brave souls that the fighting along Bull Run, in fields, groves, and a line of trees just up the pike from Manassas, became the first major encounter of the Civil War. The Confederates routed the Union army and sent the men in blue retreating pell-mell, following much the same route (in reverse) that Taft and his party had driven that day, fleeing east across the Potomac and home to Washington, D.C. Walt Whitman had chronicled the panicked, distraught, defeated Union army: “The men appear, at first sparsely and shame-faced enough, then thicker, in the streets of Washington—appear in Pennsylvania Avenue and on the steps and basement entrances,” the poet wrote. “They come along in disorderly mobs, some in squads, stragglers, companies. Occasionally a rare regiment, in perfect order, with its officers marching in perfect silence, with lowering faces, stern, weary to sinking, all black and dirty.”

President William Howard Taft addresses Union and Confederate veterans at Manassas, Virginia, in July 1911, fifty years after blue and gray soldiers fought one another in a nearby field. “You who have suffered war,” he told them, “will appreciate what peace means.” (Courtesy of the Manassas National Battlefield Park)

Everyone had predicted a quick finish to this conflict. Instead, the war wore on for four more bloody, agonizing years.

“I deplore war,” the president told the veterans. “I wish it could be abolished entirely. But we may all rejoice that in that awful test the greatness of the American people was developed. There we showed our ability to fight out our differences to the very death and to make the greatest nation in the world after having had the greatest civil war the world had ever witnessed.”

Speaking directly now to those old men in the crowd, he said, “When we look back to that period, a feeling of sadness must overcome us, for that is a period that we dislike to look back upon, a period of discouragement and sorrow, reviving in our minds all the great strain and trial of that awful struggle.… You who have suffered in war will appreciate what peace means.”

More of the veterans cried, leaning on their wooden canes or unable to stand at all. Some raised a feeble whoop and the Rebel yell. Those in blue tipped their black, gold-corded hats in a round of cheers. The applause grew louder when the governor of Virginia, dressed in Confederate gray, rose and shook the president’s hand. William Hodges Mann was the last Confederate soldier to serve as governor of the commonwealth. The president, by contrast, was a Northern man from Ohio, who had been just three years old when the guns sounded at Manassas. The symbolism was lost on no one. The two sides had officially reunited.

The great Peace Jubilee that summer was the brainchild of George Carr Round, a Union officer who at war’s end had moved to Virginia. He came up with the idea after reading a letter to the Washington Post from a South Carolina Confederate who had argued that the fiftieth anniversary of the Civil War should be honored as one of “peace and reconciliation.” Now practicing law and serving on the Manassas school board, Round suggested that the place to pay tribute to the shrinking ranks of blue and gray soldiers who had fought that war was where it began. By the time of the Jubilee, Round was already seventy years old. He would not live to see eighty.

The son of a Methodist preacher, Round was born in Pennsylvania and raised in New York. He left college before graduating to join the 1st Connecticut Artillery in 1862. After two years he was transferred to the Signal Corps and commissioned a lieutenant. The war proved a long slog for Round, as it did for many during those years of battle, retreat, and battle.

“Dear Mother,” he wrote home in October 1864. He was then at the Signal Corps camp in Georgetown, just blocks from the White House. “It is now ten o’clock in the evening. I have been on the hill close by here all day … in charge of a signal station. It was quite cold and very windy, although the sun shone brightly all day. But I bundled myself in my overcoat and had a first-rate time talking with a man down at the Provost Marshal’s office in the city of Washington.”

Round also served as signal officer for Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman as he carved the last of his famous march up the coast of North Carolina. Round climbed atop the high dome of the capitol building in Raleigh, now held by the Union army, the perfect spot to fire his signal flares. From that perch, he heard below the click of horses’ hooves. Maybe drunken cavalrymen out of camp, he thought. But as the horsemen drew near, he could make out their yelling. Then a lookout shouted, “Hurrah!” Round, a small, young man with a thin beard, a Yankee officer sitting atop the highest point in a captured Southern capital city, knew instantly what it meant. The South had surrendered; the fighting was over. He aimed his signal rockets heavenward, lighting the night sky with what became the last Signal Corps message of the war: “Peace on Earth, Good Will to Men.”

Round returned to civilian life and college and moved to Manassas. He lived in a large antebellum home, and each day around 11 a.m. his wife would step out on their porch and watch for him to depart his law office on Center Street. (If he waved a handkerchief, it was his signal that he was headed home for lunch.) He built community schools and lined the town streets with shade trees. He pushed for a national preservation battle site where Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson made his famous stand near the copse of trees. But his greatest passion was seeing the Jubilee underway. Just as he had done as a signal messenger, he sent out the word. He had ribbons sewn up and honorary badges struck for the veterans. He persuaded the Northern president and the Southern governor to attend. He commissioned poems, prayers, and songs to be sung.

A new peace anthem was drafted. Food, water, and other accommodations were arranged. But the two sides had once been bitter enemies, and not all came together without controversy. Three days before the Jubilee, the Grand Army of the Republic’s chapter in Brooklyn, New York, adopted a resolution of protest and sent it to the White House. They asked President Taft to refuse to appear if the Confederate battle flag, the old Stars and Bars, were unfurled and flown there: “Speaking in the name of the comrades who are living and more earnestly and solemnly for the million maimed and dead comrades of the armies of the Union, we protest most emphatically against such an act and demand that the President of the United States take such action as may be proper to prevent it.”

The Grand Army’s resolution demanded that the Confederate banner be ceremoniously vanquished once and for all, and what better time and place than the Jubilee reunion. “Dig a grave, broad and deep, in the soil of the battlefield and publicly bury the Confederate flag,” the Yankees demanded.

That set off howls from the Southern side. The Manassas Democrat newspaper editorialized that the Union veterans were missing the point of the reunion. The paper lamented that “such sectional feeling still exists and that it should be expressed at the inauguration of a great peace movement, at a time when the North and the South are being united in friendship with all differences cast aside, is indeed regrettable.”

George Round, ever the messenger, sent an urgent press dispatch to the nation’s wire services and told his Northern friends that both blue and gray would be recognized. “The Jubilee decorations floating from every part of our town include a thousand square feet of the National colors to every ten square feet of the Confederate colors,” he wired. “The Confederate battle flag works beautifully into the prevailing design. Abraham Lincoln loved to hear ‘Dixie’ and I love to see the battle flag which represents one of the greatest military powers in the world’s history nestling so quietly and lovingly in the folds of the Stars and Stripes.” “I invite my Brooklyn comrades to come and join our Jubilee,” he added.

Pickpockets were another nuisance, and they smoothly worked the swelling crowds. B. C. Cornwell told police he had lost his pocketbook, including cash and a $25 check. Gone were Wilber Clark’s wallet with $20 and his train ticket home to California. After the celebrations, nine pocketbooks were found wrapped in a discarded newspaper under a warehouse on Railroad Avenue—all were empty.

But except for these minor distractions, the Peace Jubilee of July 1911 went mostly without a hitch. And while speeches and political hoopla played out on the courthouse grounds, the most somber and memorable moment came earlier in the day at the battle site. There, forming a double line, the 350 ex-Confederates faced north. A dozen yards away, 150 Union veterans faced south. On cue at precisely noon, they advanced toward one another, not with rifles and fixed bayonets but with outstretched arms. Above the Southern line one solitary Virginia state flag waved in the air, the only banner held by either group. They shook hands and patted backs. They recounted old battle tales, and many agreed that their war had been a complete “misunderstanding.”

Next followed the speeches downtown and, that evening, after the politicians were gone and the air was quiet again, the clanging of the dinner bell. The old men shuffled up, headed for long tables filled with plates of fried chicken. At nightfall they sat around the campfire. As the light sputtered out, one of the Rebels sang:

I’m an old Confederate veteran,

And that’s good enough for me.

Another voice heard that night was that of James Redmond, a former slave who lived on the Manassas outskirts, a mile or two southwest of the battlefield. Back in July 1861, when much of this ground was blackened by fire, he had been pressed into burying the dead at Bull Run.

“The Southern soldiers were going about the fields picking up dead men and burying them, but the bodies were still lying around thick,” he recalled. “I saw lots of wounded men, crying for water. So I took a bucket and filled it and carried water to what I could. There were a lot of soldiers and colored men doing the same thing. There were about as many wounded of one side as the other, but it didn’t make any difference to any of us which side they were. They all got water just the same.”

Redmond, now ninety-seven years old, shook his head. “No sir,” he said. “I don’t ever want to see any more war.”

There was another man named James at that Jubilee. He was a white man and a Northerner, and he said he was a Yankee veteran who had come to the reunion from his hometown of Erie, Pennsylvania. James E. Maddox complained to the Washington Post that many of the Manassas women refused to give water to thirsty Union veterans at the reunion.

“If Manassas is typical of the hospitality of the South, then I don’t wonder the Union soldiers ran for Washington in 1861,” he boasted. “It was the best thing they ever did.… From everything that was told me by Confederate veterans, it was plainly evident that the women of Virginia are as bitter as they were ten or twenty years ago. In the midst of this scene, where men were greeting each other and forgetting the wrongs of other days, the women maintained an icy attitude.” He said one Confederate told him that “we men who fought against you are willing to forgive and forget. As far as we are concerned, the friendship we pledged today is real and sincere. But our women will never forgive the North.”

The locals, led by the Jubilee chairman, wasted no time in firing back. George Round posted an open letter “to my fellow citizens of Manassas,” calling the allegations “fabricated and false.” He said it was “Satanic malignity” designed to “fire the Southern heart.” He called for a retraction from the Post. How dare someone, especially a Yankee, impugn the dignity, grace, and gentility of Southern women, the flower of the old Confederacy? He hired H. A. Strong, a leading attorney in Erie, to find out what he could about this “alleged Yankee.” Get to the bottom of James E. Maddox, he instructed.

Strong checked the Erie city directory but could not find Maddox listed. He interviewed three members of the local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), all Union veterans of the Civil War. None had heard of Maddox. The quartermaster of the GAR post checked the membership rolls as far back as twenty-five years, but “no such name appeared.” Strong inquired at the Pennsylvania Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home in Erie. “They never heard of this war veteran,” Strong wrote in his report to Round.

Strong visited all three of the Erie daily newspapers and talked with the editors. None knew a whit about James E. Maddox. The editors did, however, advise Strong that no out-of-town correspondent had been in the city to interview anyone, so this Maddox must have been interviewed at the Jubilee in Manassas.

Former Confederate soldiers, their hats doffed, reenact Pickett’s Charge during the 1913 Gettysburg reunion. For the South this was the turning moment in 1863 that ultimately brought defeat. (Courtesy of the Gettysburg National Military Park)

In finalizing his report, Strong urged the Jubilee committee to find Maddox and unmask his true identity. The Manassas newspaper also called for swift vindication. “Let us have this man’s name, please!” the paper cried. But the investigation turned up no further details. At a time when the old warriors had come together in peace to heal the wounds of war, to shake hands and pat backs, this one man had singularly managed to mar their triumph. They dismissed him as a fraud.

THE NORTH HOSTED THE SECOND great reunion. Two years after Manassas, the remnants of the two armies gathered for the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, at a rural Pennsylvania crossroads between Baltimore and Harrisburg. Here Lee had invaded the enemy’s home, hoping to encircle Washington, cut off recruits and supplies, and force a truce. But the Union forces beat him back, especially after Confederate infantry wildly dashed across a sun-dappled peach orchard at one o’clock in the afternoon, led in part by Maj. Gen. George Pickett. This time it was the men in gray who turned and retreated back across the Potomac.

“I went down the Avenue and saw a big flaring placard on the bulletin board of a newspaper office, announcing, ‘Glorious Victory for the Union Army!’ ” wrote the poet Whitman. “The Washington bells are ringing.”

The Gettysburg of July 1863 would best be remembered for names such as Meade and Longstreet, Cemetery Ridge and Little Round Top. First to arrive for the reunion amid these old monuments, what the South would later call its high-water mark in the war, was a veteran who gave his name simply as P. Guibert. He said he had fought at Gettysburg as part of a Pennsylvania regiment. Not wanting to miss the reunion, he had left his home in Pittsburgh on May 26—walking. He strode into Gettysburg on June 13, two-and-a-half weeks early.

President Woodrow Wilson, born in Virginia and schooled in New Jersey, delivered the chief address. His earliest childhood memory was hearing that Lincoln had been elected and that war was afoot. Like Taft at Manassas, Wilson challenged the veterans to become symbols of peace rather than relics of war: “We have found one another again as brothers and comrades in arms, enemies no longer, generous friends rather, our battles long past, the quarrel forgotten. We shall not forget the splendid valor, the manly devotion of the men then arrayed against one another, now grasping hands and smiling into each other’s eyes. How complete the union has become.”

Also like Taft, Wilson’s remarks were not the highlight of the day. The spotlight fell on the veterans, especially when a group of grays reenacted Pickett’s Charge. Feebly, with canes and walkers, some holding onto one another, they limped with backs bent across a small portion of the orchard and joined hands with their old adversaries in blue.

“It’s jest about as hot as the last time we all charged,” said one of the Confederates. A Yankee remembered gunning them down as they raced at him: “We shattered their lines with our fire, and every time they just closed up and closed up again as if nothing had happened and kept right on.”

The old veterans gathered like brothers now around the Bloody Angle, the spot where Confederates had fought desperately to break the Union line. “The place is right here,” recalled one of the Rebels. “I was shot right here where I stand now. I would have died if it hadn’t been for a Union solder who saved my life. I’ve often wished I could see him but I never saw him after that day.”

A Union veteran turned sharply around. “That’s funny,” he said. “I was at the Bloody Angle too, and there was a Rebel there who was pretty badly hurt. I first gave him a drink of water, and then I took him upon my back and carried him out of the line of fire to the field hospital.”

“My God!” cried the Rebel. “Let me look at you.”

The Confederate stared deeply into the other man’s eyes. He grabbed the Yankee by the shoulders. “You are the man!” he shouted. They hugged and traded names. The Confederate was A. C. Smith of Virginia; Albert N. Hamilton of Pennsylvania was his Union savior.

That Pennsylvania summer of 1913 some fifty thousand veterans gathered at Gettysburg. The youngest, who had been a drummer boy at Shiloh, just nine years old when the war broke out, was sixty-one now. The oldest claimed he was a spry 112.

The state legislature authorized $500,000 to help fund the reunion. The money also paid railroad fare for any Pennsylvania Civil War veteran strong enough to make the trip. And they came, 22,103 from the home state alone, including 303 who had fought for the Confederacy. In the South, the Virginia chapter of the United Confederate Veterans supplied UCV uniforms for their war heroes.

Comrades now, veterans in gray and blue shake hands at the 1913 Gettysburg

reunion, much of the old animosity healed after a half century of peace.

(Courtesy of the Gettysburg National Military Park)

Army engineers tramped around the fields of Pickett’s Charge and chose that crucible spot for the main campground. The army built hundreds of tents, benches, and boardwalks, in all encompassing some 280 acres of battlefield. More than 500 lamps lit up the night, and thirty-two water fountains slaked a massive summer thirst. Two thousand cooks and bakers ran 175 open-air kitchens. For old men, the veterans ate well: 14,000 pounds of chicken and 7,000 fruit pies. Pork roast sandwiches proved a particular favorite. Ice cream helped beat the heat.

Makeshift hospitals and first-aid stations were stationed nearby. Boy Scouts escorted the weak and unsteady. But the reunion took its toll. Nine of the old men died during the weeklong festivities; the heat and humidity as much as their age did them in. August D. Brown of Maine was the first to pass, succumbing before an Army surgeon could reach him. Edgar A. Bigsley from Wisconsin died in his sleep in his tent. At the close of the week, H. H. Hodge of North Carolina dropped dead among the crowd headed home from the train station.

News also arrived of veterans who had died at home, too ill to join their comrades and adversaries at the Gettysburg reunion. Gov. Louis B. Hanna of North Dakota, in one of a series of testimonials during the encampment week, told how a Confederate veteran had just passed away in one of the Northern states. He was buried by ex-Union members of the Grand Army of the Republic at a GAR cemetery. At the gravesite, the GAR commandant told the assembled, “We cannot understand why this man fought for the Stars and Bars while we fought for the Stars and Stripes. But it is enough to know that each man fought for the right. And now, in the spirit of charity and fraternity, we lay him to rest, the Gray beside the Blue.”

In Gettysburg they finally broke camp and groups of old men started for home. But as they departed, the peace and goodwill that had sounded throughout the Jubilee was suddenly shattered. In the packed dining room of the Gettysburg Hotel on the town square, seven men were stabbed when a veteran in blue overheard some unkind words about the martyred Lincoln. The fight started suddenly and ended quickly. Knives flashed and bottles were thrown. Women fled for the exits; other ladies raced for the windows, trying to squeeze out. Should there ever be another reunion, they all agreed, let us please close the saloons.

ONE MORE LARGE-SCALE REUNION was to come.

Paul L. Roy, editor of the Gettysburg Times and executive secretary of yet another reunion committee, labored hard to pull off a seventy-fifth anniversary encampment in July 1938. He faced several obstacles. How old and feeble were the men, and how many were left? And would those still living join hands yet again?

“In my years of preliminary preparation and planning, I failed to reckon with certain unreconstructed factions in the South,” Roy wrote afterward, “and equally stubborn and irreconcilable forces in the North.” He found pockets of Confederate and Union veterans “together with allied groups who, for some time, had been trying to guide” their own separate destinies.

The early 1930s had seen a series of state reunions in the South, in places such as Shreveport, Louisiana, and Jackson, Mississippi. In the North, the GAR staged its own get-togethers. What Roy wanted was one final joint reunion of the two colors. The Confederates invited him to discuss it at their meetings, but they always turned his idea down unless they could be assured their flag would be welcome. The Northern men, however, did not want the Rebel flag anywhere near them.

So Roy traveled often to the South, hoping to broker a compromise. In Jackson, at a meeting of Southern veterans, he urged one more joint commemoration, and again the South said no. Then the United Confederate Veterans organization endorsed his compromise of separate sections for separate flags. About to leave the auditorium, Roy at last felt hopeful. Then he stepped outside.

“Several women blocked my way and started to harangue me as a ‘damn Yankee’ who was ‘trying to kill our veterans,’ ” he recalled. “Two women scratched my face and tried to tear my coat off, all while shouting and shrieking unprintable accusations. But I managed to elude their clutches and escape to my hotel room.”

The flag issue continued to vex veterans from both sides. James W. Willett, a ninety-one-year-old former GAR commander in chief from Tama, Iowa, said, “I won’t vote yes if they are to have their flag on display.”

“They can go to hell,” exclaimed his Confederate veteran counterpart, Rice Pierce.

M. J. Bonner, a national leader with the United Confederate Veterans organization, worried that if the two old armies met again without the flag controversy settled, “the war would be renewed.”

David Corbin Ker, the last surviving Rebel in Richland Parish, Louisiana, was so angry that his wife had to hold him back from going to Gettysburg and flying the Dixie flag in defiance. Ker had enlisted at fourteen, he said, in the second year of the war, and had served under both Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee. He said he hailed from a family of “fightin’ Texans,” and that his father and two grandfathers had seen duty in the War of 1812. Ker liked to boast how his father was a major in the Battle of New Orleans. As for himself, he served mostly in Virginia. But “all through the war I tried to get with the Bloody Texans, where I belonged but couldn’t make it. I would have much rather been with them because they knew how to fight and didn’t mind it. Oh, I got a few scratches during the war. Maybe some people would call them wounds, but a fightin’ Texan wouldn’t.” Now he was going on ninety-one and was still ornery. He kept a small farm near the town of Mangham, after moving to Louisiana to be near his daughter. Asked why at his age he still had rosy pink cheeks, he admitted that most of the heavy work around the place was done by an “ancient Negro.” But Ker still got around okay, and he was determined not to go anywhere where the Stars and Bars was banned. “My wife don’t want me to go because she thinks I’ll get in another fight with them d— Yankees,” he said. “And maybe I would.”

Harry Rene Lee, even older at ninety-eight and adjutant general of the national UCV, firmed up the Southern position when he warned, “No flag will ever lead ours. The American flag can be on the right, where it belongs, but it must be even and even.”

The standoff eventually was resolved with Roy’s compromise. Each side would fly its own banners in their own camps at Gettysburg.

There still remained the larger question. By 1938, Civil War veterans were passing away at the rate of 900 a year. It was guessed that a little more than ten thousand were still alive, and no more than two thousand could be expected to make the final trek to Gettysburg, given that all but a few of them were well over ninety.

Organizers found little problem locating and verifying Union veterans. Their service records were intact and many belonged to the GAR, the fraternal body of state chapters for former Yankee soldiers. Finding Confederates proved more difficult. Many records were lost or incomplete, file folders gone altogether. Southern home guards and guerrilla units had enlisted soldiers for short periods to protect communities, and those service rolls had long been misplaced or destroyed—if there ever were records. So the reunion committee’s ground rules stated that if no records existed, or a man was not a member of a veterans’ group or did not receive a Civil War pension, he would not be invited.

Formal invitations were mailed to 10,500 men. In 2,243 cases, the letters were returned marked “deceased.” Others sent regrets. “I am very deaf and my sight is failing, but if I am able I will be glad to come,” William Perrine of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry wrote to the committee. His daughter, Gertrude Van Nest, mailed a follow-up letter the next month to Gettysburg. It would be too much for him, she said. “The excitement of going has upset his mind. He is ninety-four years old and never traveled very much, as he has been very deaf since the war.”

About 1,845 blue and gray veterans eventually crowded into Gettysburg for the final hoopla. The vast majority were Yankees, if only because Pennsylvania was closer. Albert Woolson, the former Union drummer boy who by the 1950s would lay dying in Duluth, was on hand. Walter Williams, his Confederate counterpart, stayed home in Houston, though most of the men in gray who did make it to Gettysburg hailed from Texas.

Roy and his committee set up first-aid stations and wellness centers around the battlefield. A regimental hospital with 140 beds was opened in the dormitory at Gettysburg College. Wooden walkways were installed, and wheelchairs rolled out. Boxes of soap, brushes, and other toiletries were carted in. Sewer lines were dug. Barbers clipped beards short enough to beat the July heat. Each veteran in every tent was given a cot and mattress, and handed a pillow, sheets, and a wool blanket. The tents came equipped with electric lights, wash basins, soap and towels, canes and walkers, and in some cases stretchers. Many of the men dressed smartly in their old battle regalia (if they could still fit into the pants and jackets) and sat on lawn chairs to pass the long afternoons. Most fell asleep.

The keynote speech was again delivered by a president. Franklin Delano Roosevelt phrased all the right sentiments about peace and brotherhood for a once divided nation. An Eternal Light Peace Memorial was set aglow, and the president proclaimed that all the old men in their old colors “stand together under one flag now.”

Perhaps more poignant were the words from Dr. Overton H. Mennet of California: “I see here before me a beautiful national military park where once men lay in agony.” The commander in chief of the GAR and a former Indiana infantryman, he appeared resplendent in his double-breasted blue Union jacket, gold-corded, broad-brimmed hat, and bow tie.

The Southern cause’s words were put to music, as the bands played “Dixie.”

Suffering aches and arthritis, ears that did not hear and eyes that could not see well, legs no longer sturdy enough to manage their failing, ailing bodies, many of the veterans nevertheless had arrived in Gettysburg in high spirits. John Milton Claypool, a ninety-two-year-old retired preacher and Confederate commander of the UCV post in Missouri, joked that “since the Lord has put up with the Yankees all this time, I guess I can also for a few days.” Alvin F. Tolman, a ninety-year-old Union man who still drove his own car, motored up from his home in Florida, arriving early at the encampment. He teased that he wanted “to get my pick of the Gettysburg women.” Charles W. Eldridge, wounded five times by Confederates, celebrated his 107th birthday during the reunion. “Never had an ache of pain,” he claimed. “I’ll feel good for another ten years at least.”

From California 121 veterans had boarded special trains and headed east to Pennsylvania. From Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, and Missouri came 450, mostly Confederates. Louis Quint drove down from Minnesota at ninety. Ninety-two-year-old A. G. Harris, once a Confederate major general, was escorted by his son, Homer, who had soldiered in World War I. Warren Fisher of California, a Union soldier in two dozen engagements, was ninety-two years old and brought Daisy, his sixty-four-year-old wife. A North Carolina man brought his bride too; he said he was 105, and his wife thirty-eight.

Many of them achieved incredible feats of endurance. Ninety-six-year-old M. A. Loop from Sacramento, California, climbed the stairs to the top of a seventy-foot steel observation tower on Oak Ridge. The ex-Yankee wanted a panoramic view of the battlefield and encampments, but also to escape the autograph seekers down below. He came down the steps without stopping to rest. James Handcock, who had traveled to Gettysburg from the Confederate Home in New Orleans, snuck off for a day of sightseeing in Philadelphia. Police found him sound asleep at a ball game, his pipe in his mouth. He told the police he was 104.

Despite all the health precautions, by the time the reunion ended five of the veterans had died in Gettysburg. One was John W. Weaver Sr., a Tennessee cavalryman during the last year of the war, who later farmed, ran a saw mill, and shoed horses. He had married twice and outlived both wives. He was eighty-nine now, and his heart gave out in a Gettysburg hospital. Another veteran died on the last day of festivities at a hospital just outside of town. Six more collapsed returning home.

Rumors floated about plans for an eighty-fifth reunion. “I wouldn’t put anything past this crew,” said ninety-seven-year-old Samuel B. Hanson of Philadelphia, a Union veteran. “Some of the boys are struttin’ around here like they’re fifty.”

Some veterans did not want to leave the reunion at all. A small band led by William W. Banks of Alabama refused to depart the federally owned battlefield park. They sent a telegram to the quartermaster general’s office in Washington asking permission to stay for as long as they wanted, or at least until the Lord sent his angels. “We have been the humble guests of the greatest nation on the earth and as such have walked on and viewed again the sacred ground and shrines at Gettysburg made Holy by the blood of patriot martyrs, North and South,” they wired. “We desire to remain here on this hallowed hill till Gabriel shall call us to that eternal party where there is no strife, bitter hate, nor bloodshed. We are one for all and all for one. Please wire immediate that we shall stay.”

Washington did not respond, and the veterans returned home.