The good part was the work, the why I was there. Hours alone in my painting studio in Fletcher, hours nearly alone in the printmaking studio. I’d go to Benson Hall to the third-floor printmaking studio in the mornings, long before other students were ready to face work. I spent the whole of one day in the printmaking studio on lettering across Michael Jackson’s face, painting the ground, outlining the lettering in pencil with a stencil, then filling in with red oxide flow acrylic. Another day, Apollo Belvedere, translucent paper on a dark ground.

Hours in the printmaking studio produced minimal results in screen-printing, where I had no experience and the liquid photo emulsion proved recalcitrant. The studio helper got the fucking red stuff out of my wretched screen, leaving me back where I started. I spent so much time over the weeks wrestling with the processes in printmaking that I hardly reached a place where the distinctive characteristics of printmaking—the textures, the contrasts—emerged in my images. Just one snarl after another, hour after hour after hour, week after week. Actually, it wasn’t all that bad, engrossed as I was in the process.

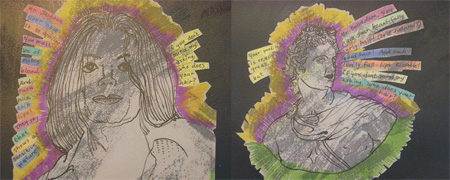

Jackson and Belvedere, 2009, hand-colored screen print, approx. 24" × 48"

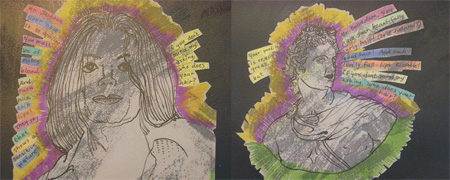

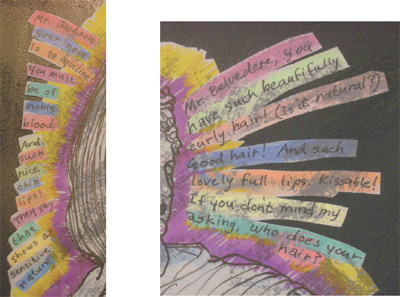

Wrestling with the silk screen, I placed Apollo Belvedere, the very quintessence of classical male beauty, next to Michael Jackson, whose remaking of his physical image into a collection of the most conventional traits of (female American) beauty has fascinated me for a long time. In my prints, they were talking to one another, complimenting each other on their appearance and asking who does their hair—Apollo Belvedere with curlier locks than Michael Jackson. The piece fell flat in crit, but I enjoyed playing with two figures of beauty from different historical eras. I amused myself in the print shop, working steadily and at my own pace alone, listening to Afropop Worldwide, Deutsche Welle, Cassandra Wilson, and Abbey Lincoln. Sometimes the other students played their music out loud.

LEFT: Left detail of Jackson and Belvedere, 2009

RIGHT: Right detail of Jackson and Belvedere, 2009

During one of my printmaking marathons, another student played a song I recognized; usually their music was all news to me, a twenty-first-century education in sound. This time the song was “Try a Little Tenderness,” one of my mother’s favorite songs.

She may be weary

Young girls, they do get weary

Wearing that same old, shabby dress.

But when she’s weary

Try a little tenderness.

I always heard it with sadness, even before her death, as an evocation of the days when my parents were first settling in Oakland and didn’t have much money and their native Californian relatives looked down on them for being from the South—Texas being the South. I imagined the song’s meaning in two ways, as my mother’s wishing my father, her husband, had tried more tenderness, and, in a sunnier version, as my mother’s appreciation that even though they didn’t have much money then, he had tried tenderness. In the print studio I teared up for my mother, her regrets in life, the disappointments she carried to her death. The song ended, my silk screen no farther along.

In light of my silk screen’s withholding, I had to resort to the unusual step, for me, of working in the print shop in the evening. I often lost track of time while painting at Fletcher, staying into the night, but printmaking at night was something new. I climbed one hundred steps from Main Street to Benefit Street and up to the third floor of Benson Hall. The printmaking studio was nearly empty, just a printmaker or two and a student monitor. As I came in, the student monitor stopped me.

Are you taking a class?

I had been so carefree going around RISD, so “moonshiny” (to use a word from THWP that was Thomas Carlyle’s dismissal of Ralph Waldo Emerson). The printmaking monitor caught me totally unawares. Concentrating on my work in a protective bubble, I had let my guard down. I had closely focused my gaze on my art and narrowed the peripheral vision I normally shared with the animals of the forest that are prey. I had lost sight of how others, strangers, might be seeing me. My guard was down, way down.

Am I taking a class? Why else would I be up here on the third floor of Benson Hall in the night? Wait, come back to the regular American world, where that isn’t so much a question eliciting information as a hurdle to be overcome. In a second, I was remanded to my country, where race counts all the time. I don’t know what was in her mind at that moment, didn’t know what she meant. It didn’t matter what she meant, what she might really have meant, because her question went straight into a tradition that I recognized, a demand for justification.

I heard her question as: This is America, and you are black. You don’t belong here.

I heard: You are out of place here. Explain yourself before you can gain entry.

I hadn’t been looking at myself through the eyes of others. I hadn’t been looking at myself at all. If I had, I would have seen an older woman dressed casually—still in my white-T-shirt-black-pants outfit from Mason Gross (but having learned from art-world observation that the white New Balance walking shoes would have to go)—not as someone scoping out the place to steal things, an interloper against whom RISD needed protection. Did I look like a thief, like someone who didn’t belong there? Did I look strange? Or did I just look black?

Before my RISD-induced swoon of art-concentration euphoria, I kept at my ready disposal a counter for inappropriate statements. As though I had not understood, I would ask the speaker of ugliness to repeat what had been said. Making an offensive speaker repeat or elaborate would usually clear the air. It’s a tactic that you can use, too. Once at a swanky dinner in the Berkshires next to the drunken lawyer husband of a member of my older women’s group, I ramped up my technique. He had assured me of my great good luck of having ancestors who had been transported to North America in the Atlantic slave trade. Wasn’t I grateful for having escaped Africa!

Oh? As if I had not understood.

Tell me more.

In a kind of nuclear option, I asked him which places were my ancestors lucky to have been delivered from, which one(s)? I dragged the offender through an examination of the current situation of every single fucking country in West Africa, one after the other in geographical order. Country by country around the coast of West and Central Africa, from Senegal right on around the Bight of Benin to Angola. I took him on an excruciating tour through his ignorance, a pitiless examination that left onlookers not simply astonished but totally aghast.

The printmaking studio in Benson Hall did not merit a bomb. Had I been on my usual guard, however, I would have asked the monitor, a young white woman, to repeat her request and clarify it: what kind of proof did she wish to see? Should I pull out my RISD ID? A class roll? But in those early RISD days, in my bubble, I had laid down my bomb, my sword, and my shield.

My guard was down, and all I could say was:

Yes.

She recognized the uselessness of her initial query; unless I really were carrying a class roll around with me or my ID as some kind of pass document, some necessary form of proof for the likes of me, how was she to ascertain I really was taking a class? She began explaining at hapless length that they had to control access to the print shop. Which was practically empty.

Was such policing the regular thing in the print shop in the evening, her question addressed to each person coming in? I don’t know. I do know that such questions routinely serve to inform people that they’re considered out of place, that they need to pass an additional test—are you taking a class?—before being allowed in.

So RISD wasn’t paradise after all. I put on my apron and looked in the drying rack for the print I had been toiling over.

Gone.

My print was gone. Someone had emptied the drying rack. My print was nowhere to be found. Was this all a conspiracy against me? To hell with trying to figure that out. Start over. I ran one hundred steps down to the RISD store on Main Street, squeezed in moments before closing, bought another pad of paper, and ran back up the one hundred steps to the printmaking studio to repeat the endless job of tearing paper and placing registration tabs.

ONCE RISD’S SPELL on me had broken, once my all-art-all-the-time bubble burst, other annoyances appeared, some really quite minor. One evening I trudged up to Woods-Gerry for the opening of a student-curated show. It had more curators—nineteen—than pieces of art.

A gigantic painting dominated the show, a life-size, 6' 7" × 11' 9" copy of the Russian artist Ilya Repin’s 1881–1891 Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, which Clement Greenberg’s classic 1939 article “Avant-garde and Kitsch” had used as its example of kitsch.7 You had to know the back story, a totally obscure back story, to understand the painting’s meaning. The undergraduate painters were free to evoke art history and history history and to come away from it with praise. How cunning of them, how clever. But this was the kind of history-based work no one wanted me, the former historian, to make. Talk about a double standard.

The rest of the show presented a hodge-podge: a large video installation of the ocean projected behind bunched-up plastic, three found paintings (one actually bought, a charming nineteenth-century seascape with a spouting whale), and sound-art and sculpture. There were nineteen different press releases. Total incoherence. Totally approved.

I was such an old fuddy-duddy among the frolicking youth, a twentieth-century relic, a repository of useless knowledge, of experience no longer interesting, a fogy wanting art to be artful.

More incoherence confronted me in the AD Colab class that had so delighted me. Collaboration—“Colab”—was a crucial part of the course, and I, always on time, always organized, always ever so disciplined, was working with young people with—how shall I say—dissimilar work habits. Yes, I was a tight-ass. Three of us planned our collaboration: a white architecture student named Greg, a jewelry maker from Taiwan named Lisa, and me. We talked and talked and talked and talked and talked. I thought we were talking in circles. Like heedless children in a playground, Greg and Lisa romped around in ideas impossible to materialize. Their suggestions would require enormous expenditures on materials, or we would have to photograph or video a performance involving an audience deeply committed to our project. Such was the incoherence. Oh, hell, I thought, what a proud ignorance of narrative and skill, naïveté proffered as cute innocence. This was so hard on my sense of clarity, but I tried to talk myself out of crankiness.

We finally produced a paper sculpture embodying the changing state of disintegration through writing in black ink on paper left out in the rain. Not so bad after all. Even better, I learned a lesson I badly needed to learn.

Letting their imaginations ramble, Lisa and Greg were absolutely right. I was absolutely wrong to focus from the outset on how we might actually pull the piece off. My AD Colab collaborators helped me unwind some, to let go and let up. I took a step away from how Glenn and I as scholars had thought for years.

Before this class, with its collaborative projects, I would have agreed with Glenn wholeheartedly that,

What isn’t coherent is bullshit.

How very twentieth-century.

How so not true.

Thanks to Lisa and Greg and AD Colab, I was losing my reverence for coherence. It was hard for me, oh god excruciatingly hard for me, to let go of reasoning that had been mine for so long. But I had to move on and adjust. I had to adapt to the DIY aesthetic prevailing at RISD and in The Art World generally, where mistakes are to remain and accidents are to be embraced.

Here were two solvents diluting my commitment to coherence—one solvent social in nature, calling up past experiences as a black American, the other solvent related to my personal proclivities, my history of thinking like a scholar, and, most likely, the organization-man leanings of my Silent Generation. Incoherence and disorganization seemed liked a test; “are you taking a class?” reminded me that RISD was as seeded with snares as life beyond art school.

So what the hell else is new, you ask.

Of course! You should have known better than to think you could escape.

Right. But I confess to have been bopping along naively, wordlessly assuming myself in a protected realm of art.

Another AD Colab experience plopped RISD smack in the middle of life in America. Once again, it was my architect collaborator, but now it was his refusal to engage with our only reading by a black author, “An Aesthetics of Blackness: Strange and Oppositional,” bell hooks’s 1990 essay on art and beauty.

hooks’s essay has three main parts. The first and third, on her grandmother’s aesthetic, open and close the essay. The central portion explains and critiques the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s. This middle section invites a discussion beyond the white mainstreams of art and design that had been our class’s subject matter up to that point. You could say that part would only interest some people. I’m trying to be generous here. I wouldn’t be one to say that, of course, because I consider black art an integral part of American art, that if you want to think about American art, you have to include black art. That’s what I think.

Be that as it may, the first and last sections of “Aesthetics of Blackness” raise obviously fundamental issues of class and consumerism that affect everyone, no matter their race or their interests in art. hooks says consumer capitalism has corrupted most Americans’ concepts of art and beauty, turning art into a commodity to be possessed. She says her poor, unlettered, quilt-making grandmother taught her “to see,” and that way of seeing reveals the connection of art to inner well-being. hooks concludes that beauty should have a purpose, to foster critical social engagement and the experience of pleasure. Quoting John Berger and Hal Foster as critics offering useful guidance, she doesn’t limit her wish to black people or black art. In AD Colab, Greg, the architecture student, didn’t see things that way.

He wouldn’t read the piece, he said; he couldn’t relate to it, because the author was black. (Gasp!)

I responded in a very, very, very even voice that did not judge my student colleague.

This isn’t an unusual response among Americans, I said, because racial difference often seems like an unbridgeable chasm.

Phoebe, a British student, joined in with, I’ve noticed that about Americans and find it shocking. In the UK, she said, all Britons are Britons, no matter their race or ethnicity.

I did not reply, Just try to tell that to black Britons.

I said the refusal was regrettable, because hooks was making useful observations about the art of people without formal education. So in addition to not pulling his weight in our collaborative project, the architecture student was a narrow-minded little twit.

I started feeling relieved not to be young in that environment, where you have to pretend that art is above material concerns, above race, class, and gender, things we didn’t talk about. I pined for a university. I wished I could have gone to Yale.

WORKING EVENINGS AT painting and printmaking, I was often eating in RISD’s imaginatively designed dining halls, a smaller one in the Fleet Library building, the larger one called the Met up the hill. These dining halls’ high ceilings magnified their importance, and the student art on their walls was engaging. Like museums that proclaim their artiness through audacious architecture, RISD’s eating halls belong to a school of design. They reminded me that I was within an artists’ realm, a place where I was starting to feel out of place.

Day after day after day I ate alone among undergraduates laughing uproariously and commiserating dramatically over what was Technicolor red-orange hilarious and what was acrylic cyan-green catastrophic. Everything new. Everything just born. Drama, always. Undergraduates’ lives were so vivid. I, on the other hand, was living in a shadowed realm in ink—black, gray, walnut. In their arty costumes and fabulous tattoos, they nuzzled one another, arms on shoulders, kisses on cheeks. They laughed some more. They chose their vegetarian meals together, paid up together, sat down together, fed off each other’s plates, and left together arm in arm. Everything mattered so deeply. I heard one man ask a woman why she was alone. The people she had eaten with had just left, she explained. She wasn’t essentially alone.

I was essentially alone. At the Met for my dinner after cleaning up and preparing my silk screen, I sat by myself, knowing no one. I always ate and did everything else by myself. I was starting to get tired of being so much alone, so different from everyone else in so many ways and so always alone.

NO MORE BUBBLE. I was now firmly back in America, where vexation accumulated. Teacher Kevin brushed off my query about Adam Pendleton, a black conceptual artist who made paintings and used text and might be helpful to me. Teacher Kevin, shifting around his Nicorette gum and rolling up the sleeves of his artfully worm-eaten cardigan, said he’d heard the name, then let it drop with a verbal shrug as though to say,

This is of no interest.

The shrug from Teacher Kevin, who could append to every noteworthy artist (to him) the name of his (usually his) gallery. What counted as interesting? Not what I thought was interesting.

And there was my exchange with Mimi the Canadian photographer over Lawrence Weschler’s profile of the Los Angeles artist Robert Irwin, a love letter to Irwin and Irwin’s 1950s LA car-culture art. I mentioned the gendered dimension of Irwin’s story. Mimi accused me of “attacking” Irwin and Weschler.

That was the word she used: attacking.

Sure, sure, this was a small contretemps, but it widened the space between me, probing a reading, and my youthful counterparts, resisting too critical an approach. I was once again out of place and dismissed as aggressive.

In painting I was groping, my work of no interest to others. The lack of concern for what I was groping toward, for what I was trying to do, deflated me. My mood seemed part of a shared discontent. Daniel, a rich Columbian second-year painting student, pronounced RISD “annoying,” so annoying that he had run off to Miami and the Bahamas with his boyfriend for a week in the middle of the semester. Even Anna, whose work Teacher Irma fulsomely praised, said she just wanted to go home. I didn’t think her dismay or Daniel’s impatience could equal my funk, but I, too, just wanted to go home. But I couldn’t just go home now, because home was feeding my wretchedness.

THINGS AT HOME—at home with my father in Oakland, I mean—were degenerating. My father, his jaunty musical outings to the university at an end, had retreated to his bed. He was driving to distraction his circle of caring friends. They would try to visit him at Salem, but he wouldn’t let them come up to his apartment. Distrusting taxis and car services, he would ask his friends to take him to his doctors. They would volunteer to take him out, but after they rearranged their schedules to accommodate him, he’d break every date, just staying home feeling sorry for himself. In our telephone conversations, he would rail and weep and pity himself as totally alone. He was not alone. He was extremely well cared for by an army of people, paid and unpaid. No one was more beloved. No one had so many people attending to him. I called him every day. All to no avail. No one could be more wretched.

Like a tapeworm traveling through the feet to the gut, like a virus jumping from one stranger to another in a subway car, my father’s depression-tapeworm-virus penetrated through the phone. He hadn’t infected me lethally, but his funk deepened my purple pall. Abbey Lincoln sang to me as I painted,

It wasn’t always easy learning to be me . . .

Being me, I guess, to be myself alone

It was lonely, sometimes, sometimes it was blue . . .

There in my painting studio, Abbey Lincoln’s “Being Me” brought on a tearful migraine and transmogrified all I was going through at RISD into grief over my mother.

My god, how I missed my mother! My mother had done what I was trying to do, my brave little mother who had reinvented herself as a writer against her husband’s obstructions. How courageous she was to come out from behind the veil of respectability to write openly and honestly about her life. I balled up my mother and Abbey Lincoln and myself into self-pitying confusion; I wept for us all—older women, older black women—in this alien place. I was wretched.

It made no objective sense, of course. Abbey Lincoln was a singer, composer, actress, and civil rights activist who shared little beyond black female beauty with my mother, who was more than a decade older and darker skinned. Lincoln had endured some hard times, harder, I think, than my mother’s. Certainly Lincoln’s entertainment-world glamour of movies and music remained distant from my mother’s local identity, which reached no farther than brief appearances with my father in Essence Magazine and Oprah as attractive, long-married elders.

I knew my mother had painstakingly reinvented herself as a writer, a vocation my father frequently undermined even before depression embittered him. She persisted, through physical illness and with the burden of an unremitting struggle against my father’s depression. I was thinking about my dear mother, and how brave she was to reinvent herself as an older woman. How hard it must have been.

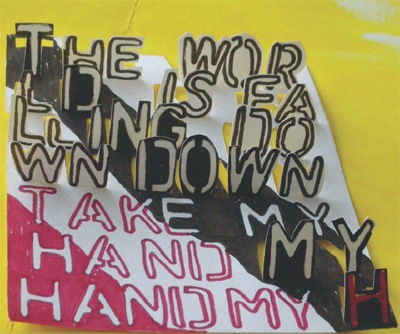

The World Is Falling Down Take My Hand, 2010,

ink on paper collage, approx. 15" × 18"

My father’s complaining, so constant, so unreasonable, pushed me into resentment. I railed to Glenn that the wrong parent had died, even that my father’s depression had killed my mother. Why had she been the one to go, she who had so much to live for, who wanted so much to live and to do. Which one had survived? The angry, depressed one, now wasting precious days in bed, now complaining about his situation and every single person seeking to help him.

Glenn and my Dear Friend Thad knew both my parents well and disagreed. My mother died at age ninety-one of congestive heart failure, they said, and that was certainly true. Death at ninety-one is not premature death. But I know depression poisons life. An Abbey Lincoln song’s plea inspired my World Is Falling Down, a print in graphic design class, still in subdued colors. It felt like me, the motherless, oldest person of all.

The motherless oldest person in this whole goddam world, eating alone, living alone, feeling alone. I hated fucking RISD, and I knew RISD fucking hated me.