Did I have peers in graduate art school? Good question, and one that didn’t come up at Mason Gross, where undergraduate art majors didn’t model professional behavior, where peers and teacher-mentors didn’t play so crucial a role in our future. As undergraduates, we were fated to be little more than Rutgers alums, maybe wearing little red R pins in our lapels or sticking blocky red Rs on our cars. But a future in art most likely meant commercial art—work for other people. Graduate school was something else again, where we immediately learned in orientation that as visual artists in our own right we were forming bonds to sustain us forever, and that we would learn more from each other than we ever could from our teachers. Our RISD painting cohort would anchor our identity as artists. It would be like belonging to a very select club. No, not like belonging. We already belonged to a club whose roster had closed.

As we made our first acquaintance sitting with drinks around a large table at Tazza, one fact united us immediately: Yale School of Art had turned every single one of us down. We were all ambitious; we all aimed at professional careers and art-world visibility. But we all had to overcome this initial falling short. We all came to RISD to work hard and intensely for two years. We all came to learn, perhaps not so much to learn technique, but to learn how to be artists in today’s Art World.

I can see that now, though I’m not sure I could see that back then, for I had not examined closely why I was in art graduate school. I just assumed I could not be a serious artist without art graduate school, just as I had known I could not be a serious historian—a publishing historian, a scholarly historian—without history graduate school. For history graduate school, I went to Harvard. For art graduate school, I went to RISD. All nine of us shared some version of that kind of reasoning, if not in so many words. We took for granted RISD’s importance in our art without stripping our assumption down to its careerist essentials, without looking hard at the assumption.

We didn’t examine one another’s family background; at least, I never came to know the details. Maybe they were more forthcoming with one another. Three were from professional New York City families, and, of the New Yorkers, one had gone to Princeton, drove an Audi, and had worked as Philip Pearlstein’s assistant, all signs of excellent connections. Another of the New Yorkers came from a family of lawyers, another from a family of doctors. There were two stocky white male Texans, one married and from a modest background. The other Texan’s father was a doctor. At first I had a hard time telling them apart. Then there was one from Maryland and another from Chicago whose backgrounds I never discovered. The one from Korea was evidently extremely well off. But for Juhyun and me, all were white. Besides me, two others—Anna and Keith, the two I got friendly with—were over thirty (them, barely) and feeling old among the twenty-somethings.

AFTER GET-ACQUAINTED DRINKS at Tazza, I got to know my peers through their work. Anna’s theme was memory, its telling and withholding, but always memory of a personal nature, not as history. She tended to work on a small scale, often in trompe l’oeil drawings that looked like photographs but that weren’t photographs, and for that they usually garnered high praise. She showed one piece listing her daily activities, hour by hour, day by day, starting with her morning oatmeal. These lists Teacher David dismissed as banal. They were banal—boring as hell. But endorsed as steps along the right way to make art now.

Keith (a different Keith, not the one at Mason Gross) took his cues from arte povera. After painting motifs from his son’s toys, he reversed his paintings to show the structures and supports, an exploration, he said, of the “objectness” of painting. He worked according to the irregularity of the handmade, creating a personal version of still lifes. His wooden lattices were praised according to their shapelessness, the more distressed ones succeeding the best. The more he made them, the more I thought of the shaped canvases of an artist I liked a lot, the late Elizabeth Murray.

The work of three of my peers seemed unrelated to their individual identities. Of course, that was not true, for even the seeming lack of personal involvement makes its own statement of self-regard. Collin worked in pure abstraction, with color and texture as his themes. He seemed so correct, so conventionally prosperous and successful, that I could not focus on him very well. Katie, the youngest and the star of our class and the only other straight out of undergraduate school, began the semester in representation, with paintings of trash bags and a disheveled apartment kitchen, always in a very wan palette. Later she moved on to abstract three-dimensional pieces made of used building materials with a blazing success that has not abated. Corydon, a physically small person, painted huge empty landscapes based on stock suburban photographs that everyone applauded. Her compositions intrigued me, not because they were unusual in their lack of figures, but because they belonged to a way of working I saw often at Mason Gross and at RISD: a landscape with no people in it. It was as though painting people—what I was valiantly striving to do—was kitschy and old-fashioned. Emptiness was favored, as in Teacher Jessica’s “deadpan abstraction” and “deadpan representation,” both, evidently, very good qualities. This quality of deadpan was not mine.

Collin used spray paint and brilliant color to make what he called “virtual vacancies,” abstract pieces that used texture and negative space to convey a sense of depth as in landscape. Teacher Irma censured Collin’s abstract painting for being too “decorative,” that is, for being too good looking, like work you’d see in a hotel, she said, where the work has to be pleasing to the untutored eye. “Ambiguity” would have been better. I agreed with her, though the work looked ambiguous enough to me. Did she want images that seemed to incorporate mistakes? I never found out and felt that as a weakness on my part.

Field explored the effects of physical forces like gravity and inertia, which made her a process artist. She spoke little in crit, but the faculty loved the impressions she made by mashing coffee filters and swinging a pendulum over her paper to leave oval tracings. Teacher Holly liked the “trustworthiness” of the process. Even so, the teachers urged Field to take a second step after the trace of the pendulum in order to turn the drawing “into something else.”

Juhyun made detailed, abstract installations in the corner of her half of our studio and a video that played on the South Korean fascination with farts. The video needed too much cultural explanation to work in our context as anything other than slapstick. In mid-semester, Juhyun left to get engaged, to get married in a lavish ceremony in her father’s factory, and to have a baby.

Of the eight of us remaining, Mike looked the most like a stereotypical RISD artist, tall, lanky, cute, blond, and lopingly relaxed in apparent self-confidence and awesome professionalism. Mike built his stretcher bars from scratch, using scores of screws (not the ordinary nails or staples like the rest of us) and special quarter-round molding to finish them off. The stretchers alone were goddam things of beauty. He photographed his work painstakingly, balancing reflected lights with multiple readings of a light meter.

I LEARNED A great deal from my peers, from how to talk about painting to what processes could lay down color and line to new drawing techniques. I adopted Collin’s and Mike’s use of a projector to scale up images to trace or paint from whatever source we wanted to take them. They told me about David Hockney’s book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, on artists’ use of pinhole cameras to produce images of previously unimaginable verisimilitude. Collin’s and Mike’s instruction helped me gain an insight on drawing, one initially prompted by Teacher Judy’s drawing exercise.

In one class Teacher Judy told us to draw her as she struck a series of quick poses as an exercise to loosen us up and open our eyes. We were to draw the old-fashioned way, with charcoal on paper, like undergraduates.

I cringed. Uh-oh, here would be my undoing.

One of my RISD teachers began every studio visit with the mater-of-fact declaration that I could not draw, and I could not paint. Like the ninny I was then, I flinched every time, believing the statement surely to be true. Now Judy was going to reveal my disability before all my peers. Anxiety. Fear. Dread. Trepidation. Palpitation.

Judy posed. We drew. After eight or ten poses, we pinned our drawings on the wall. Tensed against disclosure, I compared my drawings with the others’.

They were just as good.

My drawings were no worse than theirs.

I drew just as well as they did by hand.

Aha! My alleged inability to draw and paint was not about any failings of my hand or my eye. I just didn’t have techniques such as tracing and projection that other artists used all the time. And not just my classmates. Gerhard Richter, for example, one of the most renowned of contemporary artists and German besides, used projection as his means of creating paintings that looked like fuzzy photographs, the very paintings that established his reputation and the outsized reputation of German painting in the museums of New York City.

I finally figured out that the ritual of belittling my technique related to how art is made now. As I learned from my peers, artists commonly trace and project. All sorts of art finds its audience somewhere, no matter how—or how expertly—it is drawn or painted. The teacher’s ritual of belittling my drawing and painting meant I didn’t draw and paint the way I was supposed to. I was too stuck on subject matter. I didn’t make piles of things or paint shower tiles or empty landscapes.

Graduate school did not bind me very closely to my peers, even though they were usually quite correct toward me. I sensed they saw me, when they saw me, which wasn’t all the time, as someone inconsequential and apart from them. I never felt animus from them, just an assumption of my inconsequence and, sometimes when they focused on me, their inability—a good-natured inability, it must be said—to say very much about my work. My work walked off the beaten track. Before learning better, I thought my own autobiography made for interesting art.

I misinterpreted the “embarrassment” assignment by making a big drawing of myself as a person who was embarrassed by being the wrong kind of black person because I was comfortable financially. I made a collage I called Embarrassment of Riches, reflecting my embarrassment over being an un-poor black American. I have never felt totally, authentically black within American society, because real black Americans, authentically black Americans, are supposed to be poor, or at least formerly poor, and to have good stories to tell about overcoming adversity. I could never do that. In some ways, my inability felt like a personal shortcoming.

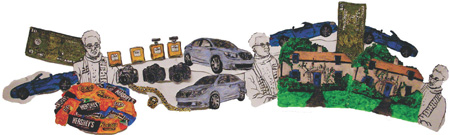

Laughing at myself in contradiction, I combined a ridiculous number of repeated images of consumer items of plentitude: multiple cars, candies, perfumes, cameras, and houses, along with a drawing of myself repeated three times. The piece was about two feet high and four feet wide, charcoal on paper, with colored objects. I left the drawings of myself in gray to contrast with the blues, greens, yellows, and oranges of the articles of consumption.

With its repetition and unnatural use of scale it certainly stood out as different from what others produced. It was dismissed as an example of illustration, illustration, a naive, unironic, straightforward, and downright twentieth-century notion. You could say that it was a work of illustration because I was visualizing an idea: one of my sources of embarrassment, my identity as a middle-class black American expressed visually in material terms.

Embarrassment of Riches, 2009, ink and acrylic paper collage, approx. 24" × 48"

My predicament as a black American wasn’t a theme that engaged my student cohort or my teachers. Well, then. Time for readjustment. In my delirious early RISD days, I thought I could let down my guard and make art in perfect candor. I was mistaken. I was wrong to think this would be seen as art. My peers and teachers were not curious about my embarrassment. Did it seem more sociological than purely personal, when the purely personal was called for? My definition of personal, my sense of myself as an individual, was too tied up in notions of blackness for the others to care. One aspect of my autobiography, however, interested them.

ONE AFTERNOON, MONTHS into RISD, I was painting away in my studio wearing a yellow German T-shirt that says “Ich bin mit der Gesamtsituation unzufrieden” (I’m unhappy with the whole situation). This was very much my thought when I bought it in Dresden in the early 2000s, when George W. Bush was president. I still have it, still unzufrieden. Right at that moment it summed up my mood in my studio, when Field, who hardly ever noticed me and never visited my studio, burst in to ask,

What year were you born?

Like Tina on George Street at Rutgers, Field had disconnected from the students’ gravitational field to enter into mine to let me see myself through her eyes. She spoke without preamble or context. No setting me up with small talk. This was not a conversation; it was a quest. How long had they wanted to know? Had they been curious, like Tina at Mason Gross, since we first met?

I imagined a student committee had deputized Field to carry out the mission, perhaps because she had gone to Princeton and we had Princeton in common. The question belonged to our art milieu, for we were professionalizing in graduate school, and the question came from the familiar formula for identifying an artist: Name (date and place of birth). Their curiosity demanded of me, as an artist, essential information.

She only asked once.

I answered, 1942.

No phone call to Mom this time, but, info secured, an immediate departure, a return to the committee in another studio breathlessly awaiting my birth date. Who won the antiquity wager? I never heard. Why didn’t they invite me into their studio to talk about our generations? Or just figure it out by themselves from the dates on my website? They told me early on they’d looked me up. How to make me feel like a specimen, to remind me I was an outsider! Ich war mit der Gesamtsituation unzufrieden.

With the exception of Anna and Keith and Mike a little bit, they seemed largely to have felt as detached from me as I from them. I did form a bond with Anna, who, like me, felt significantly older than the others—she was, what, thirty-two, as was Keith, another thirty-something old-timer. Bit by bit through speaking with Anna, I glimpsed another system of art professionalization, one as crucial as crits.

I learned that Anna and (perhaps) other painters had received multiple studio visits from visiting art stars like Nina Katchadourian.

Oh . . . ?

Nina paid studio visits to us painters?

Anna also had a crit from visiting artist Richard Meyer and from mega-critic David Hickey, though Hickey’s visits turned out to be more sexist insult than critical enlightenment. He had asked Emilia, a favored student in printmaking, her bra size. I further learned quite by chance from Anna and Mike of the existence of independent study classes with various faculty, like Dawn Clements, that I did not even know were available, and of conference calls I had been left out of.

What I saw as preferential treatment did not necessarily feel good to the colleagues I thought had been favored. One afternoon as I was stretching canvases in my studio, lanky arty Mike—the very image of the New York–Brooklyn artist—came into my studio to talk, ostensibly to thank me for taking his work seriously in my paper on Johanna Drucker for art criticism class. I didn’t kick him out, so he settled down to moan about his paintings’ reception. We students bitched everlastingly about the narrowness of his repertoire and the thoughtless sexism of his images. Which were superficial. In the extreme. Teachers were much less harsh, finding pop art and irony in Mike’s work.

I was mistaken, it turned out, to see favoritism in Mike’s independent study with Teacher Kevin. Teacher Kevin, exquisitely attuned to appearances as well as practices of up-to-the-minute New York art, seemed totally uninterested in me and my travails. Mike, in contrast, seemed to me to literally embody Kevin’s kind of artist. I assumed Kevin was taking care of Mike as the promising artist he favored, more grooming for success that left out Duhirwe and me.

I was wrong.

True, Mike was taking the kind of independent study I had missed. But Kevin wasn’t favoring Mike. Kevin disapproved of Mike’s painting and would only drop by on the fly to hector Mike to do more and better work. In fact, Mike was not Kevin’s pet. I was wrong, and not only in the case of Mike and Teacher Kevin.

Anna really was the teachers’ pet. They praised her, granted her studio visits from all the hot artists and visiting critics, lined her up with people who could ensure her success. What more could she ask?

She could ask for meaningful crits that addressed weaknesses as well as strengths of her work in terms she could understand and actually implement. When she and I had dinner together in a small, obscure restaurant on the other side of the river from RISD, she asked me for advice in getting through life—what? The star pupil looking to the class dumbbell. She said I seemed to live life knowingly, parrying RISD’s blows and deflecting its arrows, balancing all the various parts of my life. And she asked me how old I was.

Was I feeling old? Not so much right then, but orphaned, ending the first whole calendar year without my mother. Bereft. Alone. As in the disconsolate Negro spiritual, like a motherless child.

LIKE ME IN painting, Duhirwe in printmaking learned of multiple instances of being passed over for opportunities to work with prominent artists like Pat Steir. The system seemed to work like this: each department’s faculty chose its favorites, who got to meet distinguished visitors. Duhirwe and I weren’t on the lists. Emilia was on the printmaking list, Anna on the painting list. They got everything; we got nothing, even though Duhirwe was a presidential fellow, which supposedly opened The Art World to minorities. The Painting Department’s presidential fellowship went to a white male artist who knew how to draw. How it worked was how it actually worked.

Duhirwe and I were excluded from this patronage system. Lacking crucial contacts, we entered The Art World at a relative disadvantage, for personal contact with senior artists is essential to professional success. The patronage system that bypassed us disturbed Duhirwe more than me, because I had already seen it—though in attenuated form—in my previous life as a historian.

So it turned out that studio visits and crits were just the visible portion of graduate art education in a system by no means limited to RISD. An entire network of preference, favors, and connections grew up apart from classes, separating out who counted, the sheep from the goats. I figured faculty favoritism cued students into whom to consider a peer and who did not belong. This classification emerged as we eight painters were taking our class photograph. We convened in the second-floor crit room to be photographed. I was present at the appointed time, spoke to people, and set out a plate of Oreos for everyone. Then nothing happened. More nothing was happening. With things to do in my studio, I asked to be fetched when they were ready to take the photograph. I went to my studio for a moment. In that moment, they took the picture. Back downstairs, I expressed my displeasure. Vividly. They took the picture again.

A few years later I discovered a different version of the class picture on Facebook, one I was not in. My peers, my so-called peers, managed to capture their sense of themselves—without me.