Crit: the quintessence of art school. In crit your work gets taken seriously by knowledgeable and experienced teachers and thoughtful peers, people with sophisticated eyes who examine your work intently. They relate it to art history and the work of relevant contemporary artists. There might be disagreements, but all the viewers, teachers and fellow students alike, look at your work long and look at it hard. Crits are why you go to art school instead of just asking your mom and your friends how they like your work. At the end of your crit, you emerge knowing more about your art—maybe even more about yourself—with a sense of your work’s strengths and weaknesses and where it belongs within the long, wide world of art. Crit is art school’s sacred space for learning.

That, at least, is the theory.

Crits hold a hallowed place in art education, and rightly so. Starting out, I thought of crits as art school’s main event.

Crits, I learned in practice, could be just about anything. More exactly, they were the visible fraction of artists’ formation. Mason Gross crits had introduced me to the form.

Mason Gross undergraduate crits took place in the same rooms where we drew and painted. These crits were straightforward, usually with only the one teacher who had taught the class. With only one teacher, the criteria for success and failure were pretty clear.

Even when undergraduate art was thin or hackneyed or students clammed up on the ground that their art “speaks for itself,” thoughtful teachers like Hanneline, Stephen, and Barb talked about the work’s formal and conceptual qualities, finding ways to insert vocabulary we needed to know. When a drawing looked unfinished, parts remained “unresolved.” When colors lacked nuance, mixing in their complements could “unify the canvas.”

In undergraduate crits I was one of the hardworking, dedicated students who had grappled with assignments. I wasn’t the only one talking—Joseph talked, and Keith did more than his part, mentioning artists “to look at,” identifying them not only by name and style, but also by their galleries. Wow! I was impressed. I didn’t know the galleries or where they stood on the scale of coolness. I didn’t even understand how important it was in Art World eyes to belong to the right gallery. Showing in an uncool gallery was like wearing stodgy clothes.

We hard workers filled in for reluctant and silent others. I fulfilled and overfilled my undergraduate assignments, and I talked about them sitting on the floor with the kids (preening myself silently for my suppleness). One time I did a little tap dance to demonstrate my piece for the “mistake” assignment by converting a tape dispenser (one of my favorite objects to draw, with its snail-like curves and negative space) into a tap dance dispenser.

We used pushpins to attach our work to the wall, but there were never enough pushpins. After too many crits delayed by pushpin searches, I bought a box of one hundred pushpins at the little convenience store on George Street. Seven of us painting students were milling around, amusing ourselves while waiting for Teacher Stephen. With nothing better to do, I started sticking the one hundred pushpins I had bought into the wall, mystifying my fellow students.

Why are you doing that?

I continued sticking pushpins into the wall.

Because we always need pushpins to hang our work.

The others warned me, But people will walk off with them.

I kept sticking pushpins into the wall.

That’s okay. They’re here for the taking.

Mystification. Somehow pushpins seemed more valuable and hoard-worthy than the $1.39 I’d paid for a box of one hundred.

Joe, looking at my increasingly pushpinned display, noticed a change on the wall. The box that had held the official Notice of Occupancy was empty. Following the artist’s impulse to mark every blank surface, he began handwriting a Notice of Occupancy.

How do you spell “occupancy”?

Silence. Nobody could spell occupancy.

Pushing pins into the wall next to him, I spelled out in his Jersey accent,

E-C-C-A-P . . .

There came a pause, as everyone reprocessed the question and recognized the ridiculousness of my answer. We all laughed and laughed. I laughed so hard tears ran down my face. When the hilarity subsided, Joseph wrote, “Occupancy limited to 3.”

Teacher Stephen ambled in with his coffee cup (eating and drinking expressly prohibited in the studios) and house shoes, Brooklyn fashion for entering the world as an artist. Our crit began.

Joseph disparaged Diane’s earnest paintings as the pretty pictures in travel magazines. Lesson learned about sophisticated imagery: don’t do pretty; also don’t do glamorous. Jan-Vincent’s dramatic landscapes and beautiful figure paintings, all surface gorgeousness from a how-to book on painting, got thumbs-down. On the other hand, Jason’s faithfully rendered, empty scenes of the Civic Square Building’s interior architecture earned appreciation. Keith led the applause for a “biography of a wall.” Jason’s two realistic stairway paintings succeeded, whereas Jan-Vincent’s lovely woman and detailed street scene failed. JT put up figurative scenes copied from a random selection of photographs from the web, lacking titles, narrative, and concept. JT was advised to work more thoughtfully. My transcriptions of Max Beckmann portraits were duly noted, but their art history origins bored the others. The twentieth century—my twentieth century—was just too long ago to seem relevant (to use a twentieth-century word).

Undergraduate crits were also tests of basic skills, a main purpose of undergraduate art education. And there were recognizable assignments, usually a given number of drawings or paintings on a theme or technique. No problem for me, because I loved making art and was exceedingly productive. For one painting crit, my work covered a nine-foot wall. Another time I put up eighteen drawings. With that much to look at, some of it was bound to work out. Graduate crits, on the other hand, were more choreographic.

CRITS AT RISD assembled several teachers and many students in specially designated crit rooms, one on the second floor, one on the fourth floor of the Fletcher Building. A student would put up many weeks’ work and prepare to talk about it. Faculty and students would dribble in and walk around the room, inspecting the pieces with showy intensity. Then everyone would take a doughnut and an orange drink and sit in rows, faculty in front. The teacher running the crit would set a cell phone timer on thirty-five minutes to make sure everyone got the same amount of time, an excellent practice.

Timer started, the student would present the work, then teachers would talk about the work, then other students would speak up. Though plotted out as theater, the discussion had no firm rules; teachers often conversed among themselves about whatever was on their minds.

For our first crit in our first semester we first-year painters gathered as for a master class. There was the expectation—an eagerness, really—for wisdom to endure for ages and improve our work for good. Thoughtful little Corydon volunteered to take notes and send them to us afterward, a gesture of solidarity we all greeted with deep appreciation in anticipation of its fruits. As the teachers talked, Corydon typed into her laptop. Afterward she sent us lengthy reports that surely would change the way we made our art.

Alone in my studio after crit, I looked at what Corydon had sent me. Her notes were comprehensive, truly excellent. I recognized the phrases. Rereading her notes over, my mind blurted out,

Oh . . .

Oh, I thought, I just must be too tired to grasp wisdom’s meaning. I set the comments aside for later consultation. Later consultation yielded no more wisdom for the ages. Others must have experienced this disillusion. No more careful crit notes circulating breathlessly.

CRITS CONTAINED ESSENTIAL elements. There should be at least a pretense of actually looking at the work, from a distance to get a sense of its overall composition and up close for paint handling and texture. In addition to some formal analysis, there should be commentary on the work’s content and meaning and how the various pieces work together as an ensemble. It helped to mention relevant art history resonances, which usually led to the comment “You should look at . . .” followed by the name of an artist, preferably one in the art history canon or with work currently on show at a cool gallery, but in any case, not so well known as to be hackneyed.

I remembered “You should look at . . .” from Mason Gross, though I hadn’t recognized its talismanic power. I knew so little back then that just hearing about artists new to me opened up my world of visual art. Teacher Hanneline suggested I look at Velásquez as a means of improving my composition. I went and looked at Velásquez, barely grasping the connection between his compositions and mine, but enjoying the exhibition at the Met.

In RISD crits, “You should look at . . .” served multiple functions: adding to the critee’s “influences,” the store of images to draw on and techniques to adopt; demonstrating the speaker’s knowledge of art history, especially obscure art history; prolonging discussions, even competitions, with other faculty or student colleagues on hot and/or esoteric artists and galleries; and advertising exhibitions and shows currently running in New York (elsewhere didn’t count so much unless it was in Berlin, and any show in New Jersey remained beneath notice).

Early on at RISD, my own ignorance appeared in a You-should-look-at . . . lesson on how to talk and whose work to heed. Looking at a piece I had made with text, someone suggested I look at the work of Ed Ruscha. I heard the student say “Roo-SHAY.” I didn’t recognize a name I knew only from reading, pronouncing it in my mind’s ear as “ROO-shah.” Chagrin. How could I not know so important a contemporary artist?! I went to the library and looked at Ruscha’s work, which, yes, did suggest techniques I definitely could use. See, crit worked when my paintings interested my audience.

In one crit I showed a set of drawings that I really wanted to hear people discuss, as I was using photographs prominently for the second time. Were these drawings too slight to count as interesting? As so often in my work, there was a back story as well as surface appearance. Did the back story outweigh the work?

The drawings took off from a photograph in a book by a pioneering black art historian, Sylvia Boone, the first black PhD in art history and the first black woman to be tenured at Yale. Boone specialized in concepts of beauty in African art and published Radiance from the Waters: Ideals of Feminine Beauty in Mende Art in 1986. Boone and I did not overlap in Ghana in the 1960s, for she departed just before I arrived. But I followed her career and sent a copy of her book to my best friend, the Wisconsin literary scholar Nellie McKay. After Nellie’s death, her daughter, a banker, dispersed her library. A Harvard colleague with whom Nellie had collaborated bought the very copy I had inscribed to Nellie. Once she had the book in hand, the colleague recognized my inscription and generously sent me the book in Providence. I made several drawings from one of the book’s photographs as a gesture of thanks.

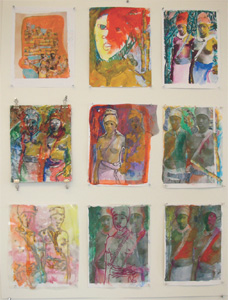

Sylvia Boone Drawings, 2009, ink on paper, each panel 10" × 8"

I selected nine of my twelve Sylvia Boone Drawings to show in crit. Fearing they might be too close to their photographic origin, at the same time, I liked them immensely. In crit, people found the back story interesting. But that was it. No one said anything about the images.

There was nothing said about the Boone drawings as artwork, not that they were visually appealing or that they were slight, not that they were intriguing, not that they might be improved if they were bigger or brighter or more or less saturated in color. Was bright color the problem?

Silence.

Silence before my Sylvia Boone Drawings took me by surprise, because they were figurative and colorful, united in imagery but separated by palette, touch, and support. Still untrusting of my eye, I couldn’t tell whether my Boone drawings were bad or boring. Maybe there just was not enough to them to be interesting. Certainly silence conveys a negative reaction, and without explanation, it discouraged me from continuing with them. I should have been stronger, because pushing on with a series holds the key to development, to moving past where you begin.

I cheated myself as an artist by being discouraged by silence in crit. For a long time, not knowing whether those Sylvia Boone Drawings were good art, only that I liked them, I cherished them as a kind of secret indulgence, as images that I alone cared for. I ultimately concluded that what happened in crit had nothing to do with anything when it came to my Sylvia Boone Drawings.

MIKE’S WORK ALWAYS elicited much more commentary. His paintings were big, 84" × 48", but always pop art objectifying women and based on the same image derived from an advertisement for panty hose. Over the course of two years the work hardly changed, but it engendered extended commentary in crit, skeptical as well as positive, that sounded like conversations about real art that took the work seriously, even though in every single crit, he would show us versions of the same flat paintings of a woman’s leg. In every single crit, students would decry the images as thoughtlessly sexist. Each time, Mike would protest that his work should only be judged formally, that is, on the basis of the surface appearance of the paint and composition. We’d say you can’t separate the appearance from the meaning, the form from the content. Then he’d make more of the same. In crit, the teachers would discuss the work at length. Teacher David said,

You seem to be in a reductive frame of mind. You seem to be painting less and less.

Maybe the paintings were lazy.

Mike half agreed, saying he was trying to distill the real.

I asked him to say more about the real. Mike answered,

They’re about so many things. They’re utterly ridiculous in so many ways, but they’re very telling.

Keith defended Mike’s paintings as really complex.

Teacher Holly, skeptical, posed rhetorical questions: What level of thinness are you insisting on, and what are we to do with that?

Teacher David decided the minimalism of the minimalist paintings worked, that they were engaging, quiet pieces, not wondering what’s not there.

Teacher Jessica agreed with Teacher Kevin, seeing Mike’s leg paintings as a ’60s pop-art package with a place in art history by virtue of Mike’s use of primary colors.

Teacher Kevin announced that although Mike had vacated and vacated, his paintings were not emptied out.

Now there was a substantive crit.

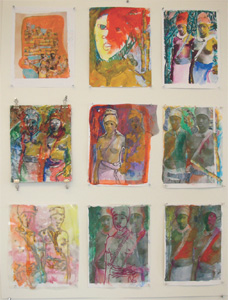

BETWEEN YOU-CAN’T-DRAW-AND-YOU-CAN’T-PAINT AND evasion, my first year of graduate school ground me down into a pathetic, insecure little stump. I made a three-sided piece in plastic that encapsulated my mood. The gray ground came from architecture software. I stenciled the words in colored acrylic ink from text taken from the book of Revelation, all about the end of the world. More of my art of end of the world.

Three-sided Woe sculpture, 2009, ink and collage on plastic, each side 12" × 12"

I should have known better than to succumb, for my mentors had warned me of art graduate school as an experience in humiliation. Artist Emma Amos, for one, had visited me at the Studio School years earlier and described graduate school as one long tearing down. She meant graduate school in general, but in my days at RISD, I felt my wretchedness, my misery, to be uniquely my own. I was wrong. Everyone I’ve talked to about their MFA experience—in poetry, fiction, nonfiction, theater, and visual art, north, south, east, and west—recognizes what I went through. It wasn’t just RISD. It was art graduate school.

During my first year of graduate crits, I couldn’t tell whether my teachers and fellow students were critiquing me, old-black-woman-totally-out-of-place, or critiquing my work, which was not good enough, TOTALLY NOT GOOD ENOUGH, or, as it felt, completely, utterly, stupidly rotten. My self-confidence collapsed.

I felt perfectly awful and alienated. There was no strength in my alienation, no saving grace. It was abject. I was P A T H E T I C.

Pathetic was precisely how I felt. Even so, misery was not all there was to me in my first year at RISD. Some of what was much more about me than misery was being an old person with a long history in the world. My much more paid off, and handsomely. With a wide circle of contacts outside my art school, I sought education in my own network of support. That network saved my life as an artist. I piled my paintings into my station wagon and drove down to New Haven, where friends in the art school and art history looked carefully at my work and talked to me about it. They gave me a crit.

In New Haven, Friends Sarah and Key Jo looked and assessed strong points and weaknesses. I said I didn’t know if the silence indicated that my Sylvia Boone Drawings were too slight—they are just small drawings, after all. No, they said, no, the drawings were nothing at all to apologize for—as I was practically doing. My friends recognized the silence before my drawings as a common reluctance of non-black viewers to engage with black figuration, a silence I shouldn’t take personally or hear as a weakness in my art. What a relief! I liked those drawings immensely and had shown them despite my uncertainty. My friends gave me permission to close my ears to viewers who were working off their own issues. To hell with you-can’t-draw-can’t-paint.

Friend Sarah, who was teaching at Yale School of Art, recognized my frustrations as a normal part of art graduate education. She also knew from experience that so many of our fellow citizens couldn’t resist the temptation to take us down a peg. Sarah and Key Jo urged me to continue with my Michael Jackson and beauty paintings, which needed work, they definitely needed work. And my friends said so. But my paintings weren’t hopeless. In New Haven I heard what I needed to hear, essential advice every art student needs to hear:

Keep on.

Keep making art.

Keep making your art.

Nonetheless, I drove back to Providence from New Haven feeling I truly did need to have my head examined for starting down the long road of visual art.

IN THE SUMMER after my first, wretched year at RISD, I gave a book talk on Martha’s Vineyard and stayed with friends from Paris. My artist host took me to see her friend, the painter Irving Petlin. In a half-underground studio, Irving worked on big pastel drawings inspired by the writing of W. G. Sebald, whose work I also admired—not just the prose, but also the use of images within the prose.

Irving sat with my digital portfolio and gave me a crit from his long years’ experience making and teaching art. My work wasn’t randomly scattered, as one RISD teacher had decreed. Irving saw a unifying hand in my work, representational and abstract, and a coherent vision of the world. On my perpetual struggle with the bane of “illustration,” he advised me to speak of “visualizing” rather than “illustrating” the concepts on my mind. Like Sarah, Irving reinforced my habit of working serially, for repetition is how art finds its way. He encouraged my work on the human figure in social context, but reminded me to stay loose. Stay loose. As a tangled-up jangle of wound-up worry, I needed that advice.

Irving sent me on to his artist friend Joyce Kozloff in New York. Joyce spent good time with me, commending my industry and my self-portraits. I share her attraction to maps, which she has been painting magnificently for decades, maps and the concept of territory, plus the process of collage, place as a fertile concept for art making. Bless her, bless him, for taking good time with my work. Life could go on.

THE ALTERNATIVE CRITS that saved my life continued with Artist Friend Denyse Thomasos, who had already helped me prepare for graduate school. She examined my work closely, explaining what she found stronger and what she found weaker, and why. Denyse reminded me that visual thinking was a language new to me and different from verbal thinking. After three hours in her New York studio, I was starting to understand what she meant. It was a matter of learning rather than of some mysterious gift of talent or inherent ability. How fortunate I was to have that extraordinarily generous, individual crit, with attention paid to my particular issues.

I didn’t have any crits at Brown, but friends there offered companionship around a welcoming dinner table. My old friend from Harvard graduate school and Princeton, the earth-shaking intellectual-administrator Ruth Simmons, was president of Brown at the time. Ruth, bless her heart, would invite me to dinners at her presidential residence, where I ate and drank like I did in my good old days. I chatted with other friends like Chinua, Toni, John, and Tricia, people who spoke language familiar to me and shared my concerns.

Even at RISD, all was not alienation, for I could take refuge with Claudia, Anthony, and Donna, African Americans who recognized the cultural baggage I was carrying in so blinkered an institution. Art historians in RISD’s liberal arts department spoke language I recognized and encouraged me.

Looking back, I can see there was more to RISD crits for me than silence and niggling fault-finding. Teachers Holly and Donna and David approached my work openly, even though they seemed not to know what to do with it or with me. They tried. Crits everywhere are as much about the person of the artist as about the art. The person I was in art graduate school was a misfit several times over.

It was my own alternative crits that carried me through. My alternative crits conferred the crucial endowment that only crits can provide—the thoughtful, well-informed focus on your work.