My historian’s life seemed to recede while I was in art school, disconnected from art as a foreign country with its own native tongue. Values that governed my work as a historian—clarity, coherence, and representativeness—looked all wrong in art. If not wrong, then not very useful, almost as bad as “academic.” The two halves of my brain, one orderly, the other spontaneous, connected only tenuously, the remnants of connecting tissue more hindrance than help. Frowning on historical subject matter, my teachers encouraged the disconnect. Leaving history seemed like what I absolutely had to do, because history was dragging me down. I knew for certain historians’ attachment to scientific truth was cramping my painting hand and misleading my eye.

Publication of my book The History of White People while I was in graduate school disrupted an already uneasy coexistence, for my tasks as an author competed with art school. Starting with an appearance on The Colbert Report the very week The History of White People was published, book promotion took me away from Providence on a regular basis. In that instance, absence increased my standing, for arm wrestling Stephen Colbert gave me impressive RISD cred. What was that like? Fun, like doing improv. Undergraduate RISD students in my digital tools class watched the video together and applauded my return to Providence. RISD’s hip young president posted my Colbert clip on his blog. My book had been favorably reviewed on the front page of The New York Times Book Review, along with a stunning graphic image of the tangled taxonomy of the idea of white people. That review awed some New York–based RISD faculty—some, hardly all—for reviews of history books didn’t count for much in the art world. I certainly did not feel any increased stature in the MFA painter’s club in Fletcher.

Between book-promotion talks and interviews, I drew and painted with the purposeful resolve of my inner worker bee, drawing and painting and painting and drawing with the discipline that was ever my forte. Immersion in work always transported me to a better place, a higher plane, a truer zone. I enjoyed every moment, all right, but beyond my studio, I still felt like an alien. While I bore down on my work over solitary hours in the studio, I imagined my fellow painters lolling about together, pleasuring themselves in Matisse-like volupté, drinking, smoking, turning up late, and schmoozing from one studio to another. They were making the work the teachers applauded, painting with knowing hands, seeing with clever eyes. They knew what I didn’t. They could drink and drug without paying a price—or so I thought. They were young enough for exemption, fresh enough not to owe alcohol’s tax in sleeplessness and looking totally rotten in the morning.

We weren’t supposed to eat or drink in our studios, but what the hell. Eno Fine Wines and Spirits, a combination wine bar–corner liquor store on Westminster Street, facilitated our drinking. Its sophisticated decor, expensive liquors, and wine tastings gave it upscale cachet, while its long hours and stock of cheap beers made it an all-hours convenience store. I wouldn’t know about all hours, but I wasn’t the only one fueling my art with alcohol. Well, I ate, too. Tazza, a self-consciously cool art-school hangout on the corner of Eddy and Westminster Streets, projected obscure European movies on ceiling monitors with music the cognoscenti recognized. Tazza served pretty good food as well as drink. Food and drink nearby, I worked steadily in my pitiful isolation. By the time of my crit with Teacher Irma, I had too many drawings to fit on my studio walls.

For her studio visit, I had put up a score of new drawings inspired by Ingres’s Grand Odalisque, Michael Jackson, and Apollo Belvedere, with two large paintings and some etchings. A lot was just regular drawing, regular painting, not objects of great beauty. But some was ambitious. I was trying to make paintings that exceeded my skill, drawing on art history and history history and trying to cram too much into my images. I might have been away from Providence a great deal, but I made up for it with a lot of work. No one, not even Teacher Irma, could accuse me of slackness. She did not accuse me of slackness. Quality, not quantity, was my defect.

She walked in as usual, reminding me,

You can’t draw, and you can’t paint.

I fell for it every time: she had plumbed the truth of the matter; she knew the real deal; I couldn’t draw, and I couldn’t paint. It didn’t occur to me that she might be saying exactly the same thing to other students, that other students might be torturing themselves as I tortured myself. I should have grasped the possibility that it was all psychological-warfare poppycock. She was probably one of those diabolical people who can sniff out each person’s particular insecurity. I had a history colleague at Penn who could do that. He’d pass on a comment impugning the teaching of one who was insecure in the classroom and whisper a critique of his book to one worried about publication. It’s a gift some people have. Maybe she had it. She tortured me, and she knew it. She did it on purpose, I just know. In my pathetic insecurity, I felt her judgment applied to me alone and feared she was right. Some of it was just for me, because I was the one juggling so many lives. Teacher Irma hastily looked around my studio, pausing over nothing. She dismissed all but one small, light-colored print as,

The only interesting thing in here.

She wasn’t there to talk about my work; she was there to complain: Why did you choose to go to graduate school when the biggest book of your career was coming out?

That’s what she said.

I heard, You stupid fart! You never should have gone to art school!

The terrible painter in me flinched.

The nincompoop that I was struggled to answer.

During undergraduate art school, I managed more than one thing. I finished my book . . .

Actually, I thought I had finished my book. I really hadn’t.

My plan had been to finish The History of White People before starting art school. I had made tremendous progress the year before, then Glenn broke my writing rhythm by dragging poor little me to Paris for the month of May, where I griped about how hard it was to work there. A chapter that had practically been writing itself in April bogged down in June. No one, not one single friend of mine, empathized. Oh, jeez! I’d been finishing this book for what felt like forever; it had, in fact, gone on for years and years. I wrote steadily all summer, but I started at Mason Gross with my book still in pieces and an intention to finish the following summer. My historical organization presidency disrupted my writing for an entire year.

Teacher Irma saw THWP as an obstacle, a fatal distraction from art school, and she was right. But she didn’t know about the obstruction that had truly disrupted my plan to complete my book before graduate school. I tended also to sublimate the obstruction, because it was so ridiculously, agonizingly, enragingly time-consuming. My book was a screen memory repressing the real distraction in my second year at Mason Gross, the real absurd drain of time and energy that dragged me down. I was president of the Organization of American Historians—OAH, the international professional organization of scholars of American history—a test in the guise of an honor.

I had belonged to the OAH for thirty years before being elected president, as I had belonged to the Southern Historical Association, of which I was also elected president, the American Studies Association, of which I was defeated in an election for president, the Association of Black Women Historians, of which I served as director, the American Historical Association, which gave me an award for distinguished graduate teaching, the Southern Association of Women Historians, the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, and organizations you had to be elected to, such as the Society of American Historians, the American Antiquarian Society, the American Academy of Political and Social Science, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. I felt it was important to be active in the historical profession, so for thirty years I faithfully attended annual meetings, served on committees, and wrote my share of reports. I did not mind taking part in professional organizations, not at all. It was the right thing to do. I was a good citizen of my profession. You get the idea.

Along with my History Department and programs in African American Studies and Women’s Studies, professional organizations had comprised my intellectual community, where I was known and respected. Some colleagues became close friends. We became leaders in our fields, and our students grew up to write important scholarship. The history profession, history history, was my intellectual home. This home opened the door, the jaws of a trap.

Only now do I recall the year when my book fell off schedule, for my memory had thrown out the endless conference calls, the wrangling, the verbal struggles, the hand-to-hand combat with only the dull bayonet of my presidency to fend off my adversary, the executive director, a man whom the sweetest of historians called “a sleazy son of a bitch.” The saving grace of that time was the comradeship of struggle forged between me and the presidents before and after, solid historians with a sense of humor, stick-to-itiveness, and guts. We proclaimed ourselves a Gang of Three forged in combat. Thank heaven for my dear presidential comrades.

The closest metaphor I can think of to describe my OAH presidency is the boulder Sisyphus had to push up the hill every day, only to have it roll back down in the night.

Here’s the morning, sunny, warm, and clear, and here’s the day’s boulder, a financial plan. You roll it up the hill. It rolls back down. The next day the boulder is a conference call. You roll it up the hill. It rolls back down. The next day the boulder is a mission statement. You roll it up the hill. It rolls back down. The next day the boulder is a strategic plan. You roll it up the hill. It rolls back down. The next day the boulder is another conference call. You roll it up the hill. It rolls back down. The strategic plan was no mere boulder. It was an eagle pecking out my liver every night.

In art school I didn’t talk about the Organization of American Historians. No one had ever heard of it, so even if I had bragged about being OAH president, people would have rolled their eyes at me in a netherworld of No Interest Whatsoever, a totally uncool realm of squares. So I have suppressed that time of travail. My presidency ended, and with its ending, the history profession passed, I assumed, into my anterior life. For years I proclaimed myself a former historian, and when asked how art school influenced my thinking about history, I maintained I no longer thought about history. Which was so very wrong.

TONGUE-LASHED IN MY studio crit by Teacher Irma, I forgot the OAH but countered with my ability to juggle several tasks at once:

I finished my book . . .

And I looked after my parents in California as my mother was dying and my father disintegrated.

That was undergraduate, Teacher Irma countered. Graduate school is different. You’re hardly ever here.

This I disputed, though I had to admit to all the entanglements of my life. I felt like I’d been in Providence a lot. I knew I’d done a lot of work, more than some other painting students. Like a chump, I carried on explaining myself as though exculpation were needed in a moment of surpassing triumph. I’m embarrassed to admit that I even sent Irma an email with the abject subject line, “It Came as a Surprise.” None of my other books had attracted so much attention, even though they’d been favorably reviewed in the New York Times and done well. At a dinner at President Ruth’s at Brown, Novelist John noted my new celebrity. He said I had finally found the right people to write about. Technically this was not true, as two of my other books had been about Americans in general. But he was right in the spirit of the thing.

A total ninny with scolding Teacher Irma, I was actually achieving a height of accomplishment. I had not only survived the devilish OAH, I had parented my parents and published a book that came in at five hundred pages in hardcover and gotten the review of a lifetime. Back at Mason Gross, I had already turned my multiplicity into art, as a collage, Chapter Revised, based on a page of my book manuscript. The ground was a wash of dark green under a page of manuscript I had shaped according to lines of text. On top of the shaped manuscript, I had sewn by hand in thick orange thread hand-cut strips of a dark red man’s tie bought at Newark’s Salvation Army. Basting the tie’s strips to the manuscript at angles to lines of typing, I obscured the text and created competing lines and conflicting narrative messages in lines as though to be read. The black-and-white manuscript, though edged organically, expressed the orderliness of scholarship; the strips of red tie, unraveling and adhered by an unsteady hand, talked over the type, posing the old riddle, What’s black and white and red/read all over?

Chapter Revised, 2006, manuscript page,

fabric, and thread on paper, 12" × 9"

So, yes, I had held it all together for years now. But, just as true, I was exhausted all the time—pressed, harried, rushed, squashed, smashed, and impossibly stretched all over the place, barely hang-ing on.

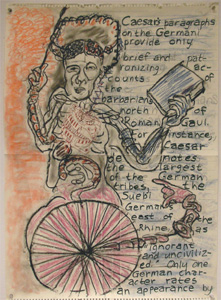

Wait, now. I was also all-powerful. Omnipotent, practically. I didn’t question whether I could balance book and art school. I even made a three-foot-high drawing in charcoal and pastel of myself doing both, with text from my book manuscript beside me, a brush in one hand, a book in the other, a Duchampian bicycle wheel for power, and a precisely drawn red alternator in place of a heart for converting one form of energy into another.

Alternator Self-Portrait, 2007,

graphite and colored pencil on paper, 33" × 23 ¼"

I had and would continue to balance book, art school, and declining parents. I’d already proven my powers. If only I had stood up to Irma with the conviction of the abilities I really had! As for mollifying her, that was pissing into the wind. Even as her hostility was turning me against graduate school, she was right about at least one thing: The History of White People, my seventh authored book, was the biggest book of my career.

ART SCHOOL INFLUENCED The History of White People, but art’s influence on my writing of history had originated years earlier. When did my turn toward the visual begin? When I was faced with Sojourner Truth, a biographical subject who did not read or write. My book Sojourner Truth, A Life, A Symbol did not turn to art history out of respect for the image. No, I was grappling with a failure of written language, a deficiency of text. The paucity of Truth’s own words documenting her life, not pure attraction to pictures, led me to art. Focusing on image in its own right came later, with art school.

The History of White People is a visual book. In the first instance because human taxonomy, though fetishizing bodily measurement, usually turns on how people look. In the second instance because race scientists have used what they call science to prove racial superiority, and racial superiority often rests on the claim that the superior race is the most beautiful. Desire is all over beauty, as in the classical judgment of Paris that I have taken you through at self-indulgent length.

WHAT BECAME The History of White People sprang from a simple question prompted by a photograph on the front page of the New York Times in 2000. It showed bombed-out Grozny, the capital of Chechnya, in another round in the endless wars between Russia and the Caucasus, and looking like Berlin in 1945. Wikipedia says, “In 2003, the United Nations called Grozny the most destroyed city on Earth.” It certainly looked that way. Knowing that Chechnya was part of the Caucasus, I couldn’t help connecting devastation over there to a common notation in the United States. Why on earth, I wondered, are white Americans called Chechens?

You hear the name Caucasian practically every day—maybe not every single day, because calling white people “Caucasian” is like calling your car your “vehicle.” “Caucasian” proclaims an elevated purpose, like scientific truth. Medical researchers and sociologists are prime users of “Caucasian,” and they don’t use it sardonically. How, I wondered, did we get from the Caucasus, between the Black and Caspian Seas, just barely in Europe and thousands of miles from the Western Hemisphere, to “Caucasian” in American usage?

The great thing about having already written many books is that you can pursue whatever question sticks in your mind. So I pursued “Caucasian” as a euphemism for the too bald-faced label of white people. Answering my question took me to Göttingen, Germany, where I found Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, an eighteenth-century professor who picked out five skulls as embodiments of what he called the “varieties” (rather than the “races”) of mankind.

Let me repeat that: Professor Blumenbach, working according to scientifically recognized methods, picked out five skulls—skulls from five individuals—and turned them into varieties of mankind. It was as though I lost my head, you boiled all the flesh off it and the brains and eyeballs out of it, and you called it “New Jersey Variety of Mankind.” I would stand for all nine million people in New Jersey. My husband, Glenn, whom I love dearly and who lives in the same house with me, would not count. It would be my skull, not his, and not yours, that personified New Jerseyans as a whole.

Blumenbach’s prettiest skull—no dings, all its teeth, nicely symmetrical—came from a young woman from Georgia in the Caucasus, a part of the world subject to slave raids over several millennia. Blumenbach (in translation) called hers “the really most beautiful form of skull, which my beautiful typical head of a young Georgian female always of itself attracts every eye, however little observant.” The Georgian who had possessed the head that became the skull had been enslaved, brought to Moscow, and raped to death. I kid you not. Her skull, the skull of a young Georgian woman raped to death, became the emblem of white people as Caucasian.

Blumenbach’s beautiful Georgian sex slave’s skull stood for a figure that art history calls the odalisque. This is where art history and art school deeply influenced my writing. At RISD I drew by hand in colored ink a small map of the land of the odalisques, a work of conceptual rather than terrestrial geography and color. Violet and green made conceptual sense for the two seas, Black and Caspian. Bleached-out yellow and orange came purely from imagination.

Wonky Black Sea Map, 2009, ink on paper, 14" × 17"

From art history I knew the countless museum paintings of odalisques, the most famous by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Grande Odalisque, who is not wearing clothes, followed by countless others, more and less clothed, by painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme and Henri Matisse. Their titles allude to slavery, slave markets, and harems, with young, mostly female beauty the constant. In the nineteenth-century United States, Hiram Powers’s The Greek Slave allowed viewers to ogle a naked white girl in the interest of high art. There is no such thing as an ugly odalisque or an old odalisque. Tipped off by art history, I chronicled the way themes associated with the odalisque, enslavement and beauty, made their way into science. I began my chapter 5, “The White Beauty Ideal as Science,” with the pioneering eighteenth-century art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who established the hard, white aesthetic for the art of ancient Greece.

Having answered my original question of why white Americans are called Chechens, I needed thousands more words and nearly a decade to complete my book. In order to refute the all-too-common notion that ancient Greeks and Romans thought in the same racial terms as we use today, I began in antiquity. Yes, yes, they could see that some people had darker and lighter skin than others. But they didn’t turn those distinctions into race, which wasn’t invented until the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. Upper-class ancient Greeks, who staged their manly games in the nude, derided their Persian enemies for being pale. In Greek eyes, Persians’ lack of suntan presented physical evidence they spent too much time indoors; paleness impugned Persians’ manhood.

After correcting errors about the ancients, my book had to come up to the present time to explain how we got to where we are now. This all took much longer than I had planned. Mounting travail exacted its toll on my own body, whose writing machine demanded peanuts and wine. I was getting fatter and fatter. My body could stand the puffing up, but the gain, oh no! made my face look its age, its old age. Either I push on with the book or I slow down, rest up, do my exercises, and, once rested up, eat right. I pushed on with everything.

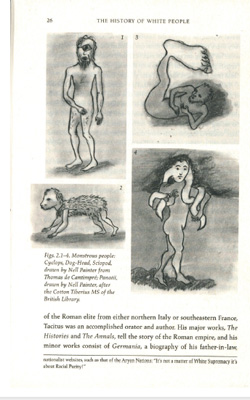

During my time at Mason Gross, my own art made its way into The History of White People has four graphite drawings on page 26, images of the so-called monstrous races of people thought to exist in the Middle Ages.

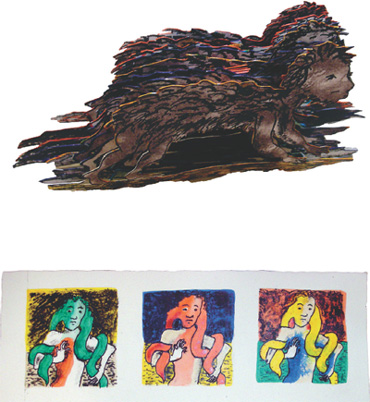

At Mason Gross, I turned two of those drawings into litho-graphs, one three-dimensional in dark forest colors, one a Warholesque multiple in Warhol-esque brightness.

TOP: Dog-head, 2009, lithograph, approx. 5" × 7" × 2"

BOTTOM: Golda’s Sciopod, 2009, lithograph, approx. 5" × 12"

History into art.