Now what?

All done with formal study, MFA in hand, a body of work still groping for its own way of seeing but a body of work nonetheless. That wave of crimson-robe-clad exultation receded, revealing conundrums both familiar and strange. I was a new painter, in the parlance of the day, an “emerging artist,” but in an old body, a body old enough for an emerging artist’s mother or grandmother who would have had more mother’s or grandmother’s skills. Artists who were actually my age—assuming they were still working—many were retired, even already dead—were so much more accomplished than I. My chronological age disqualified me for benefits intended for new painters, and many prizes outright rejected artists over thirty or forty. Other enthusiasms wordlessly discounted artists with more than a few miles on them. My lying eyes had moved into the twenty-first century, but I still couldn’t make right nowness’s grade.

I still had to push down that feeling of being superannuated, of suspecting people wanted me to go away, to disappear along with my disproportioned combination of new and old. Was I making this up? Exaggerating, if not inventing my incongruity? Very possibly. No matter how exposed I felt, there was good fortune in my now. In actual fact I was not homeless as an artist. A residency at Aferro Gallery in Newark offered me a studio to work among new colleagues. Thank heaven for Aferro, this new artist’s new home, with its mix of ages and ways of making work.

Aferro Gallery, a nonprofit, artist-run institution, sits in an enormous former furniture store on Market Street in downtown Newark in a block of stores between the former Bamberger department store, Essex County College, and the Essex County courthouse, with its statue of seated Abraham Lincoln. Some of the stores are still selling furniture to other people’s taste, but most of them are empty, one recently re-darkened after the closing of a new business, a trendy fluorescent-lit clothing store selling tight, short, low-cut dresses for the club, pointy-toed shoes for men, and accessories for giggly women who called themselves girls. Another newly re-darkened furniture store had previously reopened as an art gallery featuring up-to-date installations, huge paintings on unstretched canvas, and iconic sculptures of men’s manly parts. Glenn and I had attended this gallery’s openings before it closed for lack of sales on Market Street and moved to an even bigger space in Paterson.

At one of the old-time furniture stores still operating, the salesman stood in the doorway, regular and friendly, greeting me with his one lazy eye looking the other way. Artists coming and going to Aferro diversified a crowd of Newarkers waiting for the bus. On the other side of Aferro and beyond the huge former art gallery, a mannequin of President Obama sat smiling at passersby, sufficiently lifelike to demand a second look the first time you saw him. Here’s still there now, sitting on his bench, his paint nicked and peeling, a smile still on his face.

Aferro’s space is so long you can’t see the back from the front. The ground and second floors are exhibition space, with bathrooms and water on the second floor. Studios on the third and fourth floors. From my third-floor studio, I had to come down to the second floor to pee or wash my brushes. Dahlia, an experienced artist whose work I admired, was installed in apparent permanence on the fourth floor. Her ironic paintings used text and many shades of blue, making her, in her settled studio, my role model.

The third floor’s five studios connected, so that to reach mine in the windowless front of the building, I walked through two other artists’ spaces. If I turned toward the back as I came up the stairs, I would walk through two other studios. This configuration kept me abreast of my comrades’ work, but not in a New-York-y spirit of competition. We talked. We attended one another’s openings at Aferro and elsewhere. We organized artists’ talks and the most attentive of crits, going down the line of the third-floor studios: Katrina’s charcoal drawings. Ken’s dismembered stretcher bars. Vikki’s prints and drawings. Marcy’s tiny figures made of dryer lint. My paintings.

Aferro crits and conversations felt good, like belonging to a community of artists, something I missed at RISD despite the declaration that our MFA painting classmates would stay community now and forever. Maybe for them. It was actually happening for me at Aferro, in daily exchanges on the third floor, in artists’ talks, in shows where the public came to see our work and talk with us, and, in one instance, to ask me how old I was. Former Aferro residents like Artist Jerry Gant, dean of Newark street artists, showed work there and met me as a comrade.

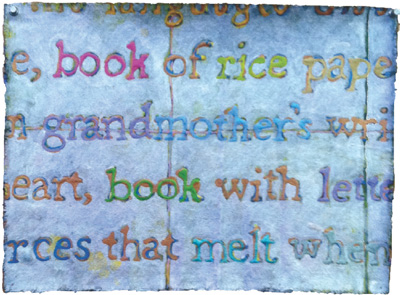

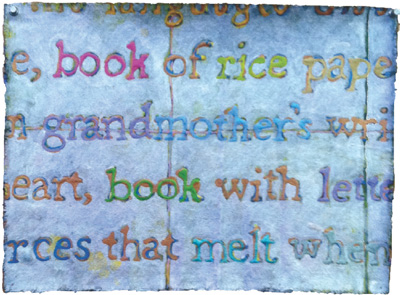

After Glenn built me a closet for my valuables—this was still the city, after all—I made my first post-RISD paintings, eight 12" × 15" works, acrylic ink on unstretched canvas, inspired by text text text!, such as a poem by my Poet Friend Meena, “When Asked What Sort of Book I Wish I Could Make,” perfect for me still with books in my blood and in my eyes. These were painterly little paintings, lush in subtle color and sweetness. Maybe too much sweetness.

Meena’s Book, Grandmother’s, 2011, acrylic on canvas, 12 ¼" × 15 ¼"

After my art-school slaps on the hand for bookishness, my fondness for words broke free. And ran all over my studio. Call it abandon. Call it belated defiance. Felt good at Aferro. Felt very very good, even a little naughty-child-beyond-teachers’-oversight.

Rolling around in text felt great for a month, then the Brooklyn paintings tugged back at me, calling me back to my digital + manual process and to larger formats. I sketched out a couple of 40" × 70" drawings on heavy watercolor paper repurposed from amateurish drawings I had made years earlier at the Studio School Drawing and Painting Marathon, then four canvases on stretcher bars. After the sketches, I went as a short-term Fulbright scholar to the United Kingdom, where I lectured in Edinburgh and Newcastle. I intended to complete these pieces in color on my return.

While I was in Britain, my paintings absorbed the spirit of Aferro’s third floor, where Katrina and Vikki were working in charcoal, no color. By the time I got back to Newark, my sketches were full of themselves in the palette they had learned from the other artists on my floor. My drawings had joined the third-floor club and wanted to belong in the company they were keeping. They said they did not want color. While I was away they had been plotting with other Aferro artists’ work in charcoal and gray dryer lint to get me in line in grisaille.

At first I resisted. Who was the painter here, and who the painted? The sketches held firm. I tried bargaining with them to let me use just a little color. Ooooo-kay. The first result was a disaster, an ornery, sullen image of muddied, grudging color that looked like the compromise that had produced it. I pulled it off its stretcher bars, rolled it up, and hid it behind the one ineffectual radiator in the far corner of my studio. Its only title was (and remains) lowercase bad painting, as in bad dog. A couple of others weren’t so awful, just paintings for other people to like. Only when I gave in to grisaille did the work start living. My Aferro neighbors’ charcoal drawings were conspiring with the gray figurative works of Gerhard Richter, the German painter whose work I had been looking at in Providence.

Richter has been a Very Big Deal as a painter for longer than I’ve been susceptible to art-world enthusiasms. It wasn’t his subject matter of German politicians and the Baader-Meinhof Gang of left-wing German terrorists in the 1970s and 1980s that intrigued me. It was his process and his palette.

Richter came back to me at Aferro as my paintings demanded grisaille. (Using a squeegee, he also makes colored “abstract pictures” he calls simply Abstraktes Bilder. These do not interest me.) On my way to his process I hardly paused over his subjects, banal scenes and ordinary people. It was his gray paintings’ use of photographs that pulled me into his work. Some digging on my part revealed his route to verisimilitude: he projected photographs onto his canvas, traced the photographs with charcoal, and painted the tracings.

Voilà! Another drawing technique that was perfectly acceptable when done in German.

I adjusted Richter’s process so that the images I projected were my own handmade drawings and paintings, hence “manual,” plus images created from them with Photoshop, hence “digital.” I had already named this way of working—my process—manual + digital. But it was really becoming more established as a process of repeated toggling back and forth and back and forth between my hand and my computer, a manual + digital + manual + digital + manual process. Settling into grisaille, I made big drawings, one I called Back Man + Cook 1. I laid down a ground in powdered graphite over a masking-tape grid, erased to create pixelated lines, and went back in with charcoal for volume and texture.

Back Man + Cook Drawing 1, 2012, graphite and acrylic on paper, 30" × 60"

“Cook” came from one of Lucille’s photographs that I had not used at RISD, though “back man” survived from my last RISD painting. Some of the paintings were very dark, others very light. None looked like anything I had made before. I could work this way for a very long time, varying my mediums and tones.

AS I WAS making a series of Back Man + Cook drawings and welcoming a stream of visitors to my studio, there came another Oakland crisis. Once again, my father was in Kaiser’s ER with elevated blood pressure and confusion, having fallen on his way to the bathroom. After a few hours in the ER, his blood pressure had subsided, and he was sent home. Was there anything else wrong with him? Evidently not. This was turning into a familiar circuit, from Salem to ER with elevated, then normal blood pressure, and home to Salem. Home to his complaints about one thing to the next. For gouging him on price. For aides treating him roughly. I couldn’t know which complaint was merited, the matter of price gouging most certainly not.

There was more. He was lonely; again, loneliness. No family around him. His eyesight was failing him, and what would he do when there was nothing left? Friends signed him up for low-sight workshops that his depression prevented his attending. They brought him audiobooks he wouldn’t listen to and apparatuses requiring more initiative than he could muster. He lay immobilized in his heartbreak hotel.

NEWARK WAS ANNOYING me now. I waited for my 27 bus on the crowded corner of Market and Broad Streets, Newark’s fabled “Four Corners” of the olden days when Newark was New Jersey’s booming retail, manufacturing, and distribution hub. That was before Paramus’s malls snatched away retail, before manufacturing went overseas, and before Exit 8A on the New Jersey Turnpike captured warehousing. So many empty offices testifying Newark’s loss.

The evening darkened, the now strictly working-class crowd at Market and Broad was thinning; yet enough foot traffic remained to prompt an amplified orator to set up below the police surveillance tower. The orator stood before five Fruit-of-Islam-looking protectors, young men so clean-cut as to appear menacing. As the light faded, the orator addressed Latinos in the no-longer-dense crowd:

You Latinos think you better than the black man because you have light skin.

You no better.

You bastards. Bastards of the white man.

You only closer to our European oppressors.

Wake up, you Europeanized bastards!

The orator was preaching black-brown unity through a detour of insult. My Newark didn’t usually seem so hostile to me. Maybe it was the season, the holidays with their impending visit to Oakland. There was Christmas music’s aggravating cheeriness. Even Nat King Cole roasting chestnuts over an open fire sounded futile in globally warmed New Jersey. We hardly had winter anymore, except for catastrophic dumps of twelve inches of snow that shut everything down for days of excavation. Did anyone roast chestnuts or even know what they were?

Oakland for the holidays just made things worse. My father, bitter in his bed, accused me of doing “nothing” for him, alternating with thanks for reading him Sherwin Nuland’s The Art of Aging. But mostly my father muttered and griped and circled back to renewing his demand to move to New Jersey.

Move him to New Jersey! What a huge, expensive, impossible undertaking! My stomach ached at the thought. The dressing and undressing. The baggage. The medications. My indentured servitude for the rest of his days.

After we left he got better. He perked up to tell his friends that moving to New Jersey was my idea, that he was only going along for my sake.

Okay, I said to him by phone. Are you ready to move?

I had found the place.

Are you ready to move to New Jersey?

Not yet.

I put my moving-my-father-preparations on hold and went to New Haven for an artist-scholar residency at Yale.

THE ENTHUSIASM OF my Yale welcome stunned me, even after the warmth of my Newark world of artists and my community at Aferro, for I hadn’t completely overcome my felt identity as the worst painter in the world. Yale people didn’t care. They embraced, even celebrated the genius of the new project I called Odalisque Atlas. Yale people, unlike my recent art-school contingent, applauded its growth out of history and art history and current events. My turning the figure of the odalisque—the beautiful, young, sexually available slave girl at the root of the term “Caucasian” for white people—into visual art seemed absolutely original and positively inspired in New Haven. They didn’t mind at all that the research came out of my book The History of White People. What a productive notion!

Yale was my Elysian Fields, my hog heaven. I could take books out of the Haas Family Arts Library. The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library let me examine pictures and manuscripts on the world’s many slave trades. Teacher Sam in the Yale School of Art invited me to pit crits and a presentation of drawings at the Yale Center for British Art. In Sterling Library I plodded through the details—and I do mean the details—of a multivolume history of Ukraine from Soviet times full of analysis of institutions and categories of objects, all mercifully translated into English. I presented a first draft of my odalisque project to the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition to an appreciative audience of graduate students and faculty. They told me,

We’re so glad you’re here.

I luxuriated in Yale’s embrace, ready to render my thoughts as images. I set up in an unused faculty office, tacked paper to the wall, and pulled out my graphite and ink. I had time and space and the encouragement to take advantage of all Yale offered me. Who could ask for anything more?

MY FATHER CALLED me in tears. Again. It must have been 8:00 a.m. in Oakland, him crying,

I can’t live alone any longer.

His call jerked me back from anticipation to my real life, from shining promise to bleak depression. From expectation to responsibility, eagerness to duty, self-centeredness to empathy.

By now I had heard “can’t live alone” many times before and knew how to interpret it. It meant I should move to Oakland. I should, as family, answer to his needs and care for him full-time. He knew by now this would not happen. That yearning was in vain and totally not to be. It meant his moving to New Jersey, even though he said he wasn’t ready, and even though his concept of moving from Oakland to New Jersey was on the order of traveling up to the Oregon border.

Okay, was he ready to move right now?

No, not yet.

I returned to my project at Yale, met my friends, ate and drank and talked. I made drawings inspired by Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, whose Penguin Classics edition I had edited a decade earlier. Jacobs’s observation on beauty in slave girls had stayed with me over the years:

If God has bestowed beauty upon her [the slave girl], it will prove her greatest curse. That which commands admiration in the white woman only hastens the degradation of the female slave.

Jacobs was writing about her North Carolina, but she knew she shared a condition with thousands of others. She was from the American South, but her words applied to Georgia in the Caucasus, the home of the odalisque.

I included Jacobs’s words in my Odalisque Atlas, even though enslaved black girls weren’t ordinarily considered odalisques. I wanted to make connections, to emphasize the kindredness of women’s experiences, of women’s vulnerability despite color-line habits of thought that would separate them. Youth, beauty, plus subjugation imperil a girl, no matter where she lives and no matter who enslaves her.

If God Has Bestowed Beauty, 2012, conté crayon and graphite on paper, 24" × 18"

I rewrote Jacobs’s words in graphite exactly as they appeared on page 46. Then I scanned my writing. Using Photoshop, I re-scaled and recomposed the image, superimposing layers of different sizes. I projected my new composition and redrew it in conté crayon and powdered graphite on paper.

In a technique I repeated later in images I made using projection, my Harriet Jacobs drawing depicted the icons at the bottom of the projected frame: “Rotate,” “Slideshow,” “Return.” Unlike sneaky Gerhard Richter, I was candid about projection as one step in my process and a feature of my sense of composition.

In addition to my drawings from Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, I was envisioning an Odalisque Atlas of imaginary maps to pull together many slave trades, starting with the Caucasus and Georgia and Ukraine, the sources of the millennia-old Black Sea slave trade that was already so old that Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BCE, couldn’t trace its origins, a slave trade into the eastern Mediterranean that didn’t end until about 1900. There was also Thailand, with its present-day sex slavery, and western and central Africa, of the Atlantic slave trade to the Western Hemisphere’s islands of the Caribbean Sea and the U.S. American South.

I would invent a new geography of submission, taking apart and reassembling the lands of the odalisque around a reconfigured Black Sea. I couldn’t wait to start drawing, to get back to painting.

Another phone call.

A family friend in Oakland was in a drugstore buying the ACE bandage my father wanted for his wrist, sore and swollen after a fall. I called my father, who offered an explanation. He had fallen, he said, walking outside by the railroad tracks in Texas. Railroad tracks in his hometown in Texas. Yes, he had been a boy beside the railroad tracks in his Texas hometown. In the 1920s.

Now add the railroad tracks in Texas to the territory my family life needed to administer:

Newark. New Haven. Oakland. Texas.

While I ricocheted between my places, the New York Times asked me to write an op-ed column on poor white people, who were becoming a hot topic. In succeeding years they got even hotter, and as the author of The History of White People, I became an expert on white people. My Times op-ed appeared while I ran between my places, now adding West Orange, New Jersey, where we were preparing to move my father with his constant need for my presence. Oakland, Texas, Newark, West Orange.

New Haven?

New Haven was ceding place to my father. His mind had moved on from walking and falling along the railroad in Texas to a series of lurid, pitiful, enraged fantasies about his wife, my mother, who had died three years earlier. She had had a baby by another man. The baby was white. She was riding on a bicycle holding the white baby. She was riding on a bicycle down Piedmont Avenue with the white baby from the Key System’s bus terminal at 40th Street. The baby was female. The baby was dead. I tried not to encounter myself in his fantasies.

Worried for my father’s life and, given his imagination, for my own, I went to Oakland. A move to New Jersey would have to come now, not later, or I would have to return to Oakland every single week.

Goodbye, New Haven. Farewell, Elysian Fields. Au revoir, hog heaven.

It seemed like forever that my father had been emotionally impaired. For the last seven years or more, never-ending scenes of tears, accusations, anger, and self-pity, but interspersed with returns to the sweet generosity of spirit, of openness, of attention to others that had made my father universally beloved.

Now depression enfeebled his physical body. He no longer walked Salem’s grounds, didn’t even go down to the dining room to eat with the tablemates he had cherished. His physical appearance degraded. His hands looked dead, doughy-colored and scrawny, with all the veins standing out over the bones, the deadly colorlessness a defect of light-colored skin. My mother’s dark-skinned hands never looked lifeless in that way, even in her mortal illness. It was as though my father’s hands had been butchered and all the blood drained away.

In Oakland with my father about to move, I was tired tired tired to death, emotionally wrung out and flattened by his complaints. The generous soul he remained glimpsed my fatigue intermittently and tried to do his part toward his move. There was so little he could manage to do that his gestures saddened me further. How to recover from his move to New Jersey? I was already so tired, and so many tasks remained. No way could I reconnect with my project in New Haven.

My spring semester’s project was moving my father, not my Odalisque Atlas. Arrangements, money, arrangements, more money, more and more and more money, starting with a check for $8,000 to my father’s New Jersey assisted-living facility. The money coursed out a Mississippi River through countless delta channels.

Saintly Husband Glenn was to fly overnight with my father from San Francisco to Newark. On our drive from Oakland across the Bay Bridge to SFO, Glenn remarked to my father that he was leaving the Bay Area after seventy years. My concentration on details had blocked that ending from my mind. Sure enough, I realized, crossing the Bay, my father was leaving the Bay Area to die in New Jersey. He knew that. The point—half the point of his move—was not to die alone. The other half was having me close at hand for trips to the ER, though Glenn, too, did major ER duty in New Jersey.

Glenn’s comment on my father’s departure from his adopted home after seventy years meant I was doing something of the same thing. For decades after my move east for graduate school and faculty appointments, my parents had anchored me in the Bay Area for at least two visits a year, more, for increasingly frequent emergencies. I’d see my parents’ old friends, my old friends, and my new Bay Area artist friends like Mildred and Anna. This was a goodbye for me as well, a kind of an ending.

After Glenn and my father left for New Jersey, I returned to his apartment. In my father’s definitive absence, a decision I had made years earlier came back to me. I was with my mother at Salem as my father was undergoing electroconvulsive therapy. In the course of ECT, his heart stopped. My father had a do-not-resuscitate order, but the doctors called my mother to ask whether they should honor it or restart my father’s heart. My mother froze and handed the phone to me. Was she afraid of what she might answer? Phone in hand, I hesitated a moment, figuring he was healthy except for having a heart that had stopped beating. I didn’t figure in his depression, which had sent him to ECT in the first place. I said, Restart his heart.

Which they did. But the heart stopping set out-of-bounds the only therapy that fixed my father’s depression, even temporarily. He was alive. He was still depressed.

That was years ago.

It was my mother who died.

Now she was dead, and he was alive and on his way to New Jersey. I made the wrong wrong wrong decision, I said to myself in his empty room. If only I could take it back and spare my father this misery. My mother, after grieving, would be a happy widow, emancipated from her husband’s depressed negativity, free to pursue her writing and play bingo in the Salem living room as often and as long as she wanted. When I had that phone in my hand, I should have taken another moment to think what “healthy” meant for someone so severely depressed. Would that I had thought more before making that wrong wrong wrong decision. The wrong parent was living, I thought now. The wrong parent had died.

EMPTYING MY FATHER’S apartment at Salem, I acted on his permission to give away cherished possessions he had held on to for years. He still had friends, good and old friends in Oakland who could share his belongings. One friend brought her teenage granddaughter, who delighted in my father’s fountain pens and a notebook whose wooden cover he had carved. Her pleasure gave me pleasure, though my pleasure was burnt-umber sadness in the darkness of earth tones.

Still, delight in a young person’s discovery of the unknown: fountain pens drawing ink from a bottle! Woodworking made by someone right there in Oakland! The pens had been instruments of my father’s pride in calligraphy and the notebook a product of his art before glaucoma compromised his eyesight and depression drained his creative spirit.

Departure changed my father’s feelings toward money. Although he had always been generous financially as well as helpful to family and friends, he had always hedged his generosity with judgments as to his recipients’ ability to use his gifts wisely. He always preferred a thrifty receiver to a spendthrift, educational expenses to consumption. And he let his preferences be known.

Now he judged less, gave more, musing on the irony of having saved more money than he could spend in the time remaining to him. That irony proved vain, for his life in New Jersey cost money by the fistfuls, even for non-Alzheimer’s care. He had probably expected lower expenses—his notions of what things cost aligned with 1970s and 1980s prices. In his mid-nineties, he was living longer than any of us expected, himself included. He had enough money for assisted living in New Jersey, but there would hardly be leftover fortunes for him ruefully to enjoy giving away.

YALE OVER. AFERRO ended. What to do now? In Newark’s Ironbound district, I rented a studio of my own whose outfitting brought back my father as he used to be, before depression, before frailty. He offered—dear old man—to help me cart a flat file weighing five hundred pounds from Frenchtown on the Delaware River to my Newark studio. That offer was my father’s old impulse speaking, his love of pitching in. By now he was too weak to manage even the few steps down to my basement studio. Back when he was only eighty-five, he could actually have helped me; he actually had helped move us to the Adirondacks from Vermont. No longer. Still, in his nineties, a sweet recall of how he used to be.