One evening after Yaddo, after Cousin Diana’s death, I had dinner in the Village with Friends Michele and Charlie from the Adirondacks. An agreeable evening, talking mostly about art and artists we knew. In the most innocuous way, Charlie asked me if I was expecting to have a career as an artist. Charlie is a real artist, making work and selling through a gallery for years, my definition of a real artist. Was I expecting a real art career?

He didn’t say it like that, of course. His words, his tone, all were totally innocent. But here’s what I heard:

Is so baby a painter as you expecting really to succeed as an artist?

Is so crummy a painter and as old a person as you going to get anywhere in art?

Probably he was just curious about the prospects of a newly minted MFA painter as old as I was.

Charlie didn’t know my exact age, or maybe he did, as my age was not only an object of curiosity, but also public knowledge, as I discovered at Jerry’s art supply store in West Orange.

I was standing in line for a demonstration of art printing papers. Printing paper is a hot topic, so the audience exceeded the seating around the expert and his printer. We stood in line fifteen minutes and more, time to strike up a conversation about our art with the woman next to me. She wanted to see my work, so I pulled out my cell phone and Googled myself.

Usually when I Google myself, my own website comes up first without my having to type in the URL, and there’s my art on it. Not this time. Not noticing a change, I clicked on the first link. What came up was a simple site with the photo from my own website—a nice photo—and a few lines of text.

The first line read, simply, age 70.

The second line, born in 1942.

I was mortified.

M O R T I F I E D

There were my age and my date of birth proclaimed for all to see, clear as the sun, stark as death. I hadn’t been able to acknowledge my birthday, so strong my consternation on turning seventy. I didn’t go as far as Jacques Derrida, who called seventy hell and wished for some way to un-age. Still . . .

What? Who? is a woman in her seventies? She is, I was, indisputably old. You can pass for middle-aged in your sixties. And I was looking forward to my eighties.

A woman in her eighties is a sage. She is dignity and wisdom. She inspires the world. She has gravitas. She is elegant. She is Maya Angelou, all eloquence and sagesse.

Eighties? Yeah!

Seventies? Arghhhhhh!

Knowing I couldn’t remove or even bury that page, I left Jerry’s stripped naked and feeling sad. The first thing anyone looking for my work would see was my age. Not that I had ever lied about my age or even fudged it by leaving dates off my CV. No lying for me. If you visit my own website you’ll see that I graduated from Berkeley in 1964. Do the math, and you’ll know how old I am. But you would have to do the math that Google had now pre-done for you.

M O R T I F I C A T I O N

In the morning I felt a whole lot better. Google, in blurting out my age, broke down my chagrin. I felt like my mother once she overcame her reluctance to use a cane (a.k.a. walking stick), because then people would know she was old. Just as her walking stick had restored her confidence, Google’s revelation gave me freedom something akin to the freedom I’d experienced years earlier when I’d stopped dying my hair and let show my gray. Then I had freed myself from the tyranny of youth—or the tyranny of the appearance of youth, of its simulacrum—over physical attractiveness. That gesture was long years behind me, now so comfortably gray haired.

The freedom produced by the bald announcement of my age was one just as precious, a freedom that I had edged up to repeatedly but failed to grasp securely: the freedom to disregard the career path that art graduate school had laid out for all of us. You could have a past, but it had to be in art. You couldn’t have responsibilities to aged parents or children or attachment to a spouse with work of his own. The fact of children had complicated the education and career path of Keith among my RISD colleagues. Keith tortured himself over his selfishness, as he felt it, for dedicating himself to the exalted-but-iffy future of a visual artist instead of providing for his family through a reliable vocation.

Assuming youthfulness, that path was hard for me. But lacking an alternative, I kept trying to walk that path, stayed attuned to that narrative. Google’s announcement of my age made me examine that path and query that narrative, both intended for youth’s lack of obstruction. For me there was family, most starkly in the person of my father, with his alternating confusion, weakness, and great good spirits. He would telephone me in high dudgeon to demand my presence right now. Then the very next day or days later and recuperated from cataclysm, he would hold an unperturbed conversation about the state of the world or his memories of the University of California College of Chemistry or his youth in Texas. He could blast me with flaming anger or thank me tenderly for his care. I never knew what each day would bring, which version of my father I’d encounter, only hoping for no fall and no emergency room.

EASY AS IT was to recognize the part family played in my past that was still with me, it was harder to see how art school had redefined my relation to history. What I heard in art school soundly rejected my history and what history meant in me.

Academic.

Academic as bad.

Academic as what things meant rather than how things looked.

Fussiness.

Tired images.

Technique in place of freshness.

Me with my lying twentieth-century eyes and my attachment to meaning.

I TAMPED DOWN that part of my past and tried to believe it no longer connected to me as something I actively thought about. This misconception ensnared me at Yale.

While I was at Yale, my Host Elizabeth chaired an interview between me and Crystal, one of my favorite former graduate students who was on the faculty. Crystal asked how art school had changed my thinking about history. Not how history entered my art, but how art entered my history.

I said I no longer thought about history.

What I meant was I no longer conducted research in historical archives and no longer wrote scholarly books. I wasn’t agile enough to give this explanation, so my answer to Crystal’s question was basically,

Duh.

Key Jo, one of the smart art history graduate students, tried to help me out by pointing to my odalisque project, so rooted in history. But for myself, I couldn’t see the connection between the images forming in my imagination and what I thought of as history, an undertaking in scholarly research that took no liberties with the archive. I felt dumb, and I sounded dumb. A few weeks later, after my talk at the Beinecke, Friends Laura and Rob posed questions much like Crystal’s. Once again, I lacked a good response. Finding that answer, I mean being able to formulate it in words, took me years. But find it I did through talking about history.

ART SCHOOL HASTENED, not initiated, my move beyond straight history. I had already embraced new tools like psychology’s attachment theory while writing on the Georgia plantation mistress Gertrude Thomas8 and the New Yorker Sojourner Truth. I was already less interested in generalities and representativeness. I was already going deeper into particularities, even where conventional historical sources failed. Now, with images in my eyes, I wanted to ask questions even when I knew I could not answer them, but when the mere asking let me focus my attention on particular individuals in the past.

In a talk in Germany I concentrated on the individuals whose skulls Blumenbach turned into the embodiments of the varieties of humanity we call races: American, African, Malay, European, and Asian. Who were these people in their own lives, I wondered. In The History of White People I had delved into the Georgian slave background of the woman whose skull made white people “Caucasian.” But what of the others? Only one, the Siberian warrior who became the Asian, had a name, Tschewin Amureew. The Malay had fallen victim to Captain Cook’s men in Tahiti. The American was a Carib chief whom Englishmen had sacrificed to empire. I said this in my German talk, taking the skull with the name only of “Ethiopian” as one example.

I knew from the archive that the skull had belonged to a woman from present-day Ghana who had died at twenty-seven in Amsterdam, where she lived with a Dutch seaman. Her missing teeth said she was a mother.9 The Dutch professor who had sent her skull to Germany called her a concubine. Was she a concubine? Was she a wife? Was she a slave? I didn’t know the answers, for the archive did not offer the information I sought. Even so, I was asking the questions in public.

Painting had taught me to slow down, to tarry over details that might seem insignificant. I lacked answers, for archival documentation failed me. But I could heed painting’s prompt to pause over what I could not know and imagine this individual woman’s existence. Making images to accompany my German lecture accorded her historical resonance that words alone withheld.

DURING THE YEARS I needed to find an answer to Crystal, Laura, and Rob about art school and history, I enjoyed myself reprising my former occupation of making books. Not in the way I had written books for other people to publish, but with little books I drew and painted in the spirit of narrative, of one thing after another, even when the narrative wasn’t apparent or coherent.

At Jerry’s—the same art supply store where Google outed me as seventy—I bought little blank accordion books that I drew and painted on just for the hell of it. I made one in colors and collaged roads with writing on them to celebrate the birthday of my Dear Friend Thad and our years together. Thad’s birthday book stretches landscape textures and lighthearted, non-landscape colors across accordion pages, with roads of text recalling places she has been and we have shared. The road strips of text trace the lengths of this friendship.

Happy Birthday Thadious Davis, 2014, accordion artist book on paper, 6" × 38 ½"

I made a simpleminded little book with text to congratulate myself for swimming thirty-three laps in the pool of the Newark Y, to say in image and repeat for emphasis that this happened on this particular day.

Thirty-three Laps Book, 2014, accordion artist book on paper, 6" × 38 ½"

And I made one in graphite and collage from the shadows in my downstairs bathroom for Poet Friend Meena. Bathroom Book for Meena has no meaning beyond the visual presentation of the daily passage of time. Only later did I connect my little book to Jun’ichiro Tanizaki’s 1933 essay “In Praise of Shadows,” a meditation on classic Japanese aesthetics that value the interplay of light and shadow. My book as a physical gift appreciates Meena’s presence as I move through the visual contrasts of my everyday life.

Bathroom Book for Meena, 2014, accordion artist book on paper, 6" × 38 ½"

I gave them away.

Around the same time I was making my little books, the New York Times once again brought me back to writing about white people. It felt very good to reach a large audience, but I couldn’t yet put together my writing history and my art. Two books in particular helped me along, reminding me of my fondness for the combination of text and image and for the drawn books of Maira Kalman, who, I had argued back at RISD, is yes indeed a painter.

One book I pulled out of my Dear Friend Thad’s bookshelf, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, by her eloquent English professor colleague, Saidiya Hartman. A poignant travel account by a gifted writer, Lose Your Mother traces Hartman’s trip to Ghana in search of the Atlantic slave trade that had ensnared her ancestors—some of them, for like most black Americans, her ancestor tangle included some who had not been enslaved and some of European descent. All by itself, Hartman’s language makes her book memorable. What caught my eyes were the photographs.

Hartman scattered photographs throughout her pages, some of her family, others of places she had been. The photographs did their work, more autonomous than simple illustration that said, “This is what that looked like.” In silent call-and-response with the text, her images sang their own song, not exactly telling their own story, but not exactly telling Hartman’s text’s, either. Oh my god! I said to myself. These images are making visual meaning apart from, but from within the covers of the book. Lose Your Mother demonstrated the possibilities of juxtaposition of text and image to make larger, broader, deeper meaning than scholarship alone.

My other text-plus-image guidebook was W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz, also presenting a traveler, European this time, exploring another historical trauma, the Holocaust/Shoah. Photographs appear throughout the book, unexplained and conveying their own indeterminate meaning. Fictional Jacques Austerlitz, like nonfictional Saidiya Hartman, fails to find his ancestors. Austerlitz reaped rewards denied Lose Your Mother. But these two books projected a contiguity of image and text that I might use.

I COULDN’T YET imagine making such a book on my own, for Odalisque Atlas remained tethered to the text of The History of White People in a spirit of illustration, as in illustration = bad. An invitation from the Metropolitan Museum of Art offered just the opportunity, just the prompt that I needed. I was invited as Nell Irvin Painter the historian to comment on “African Art, New York, and the Avant-Garde,” a small exhibit in one of the Met’s galleries, an invitation that of course I accepted. Of course, if I were going to present at the Met, I would show my own artwork. But what to show? Neither of my two bodies of work, my Brooklyn MFA paintings or my Odalisque Atlas, related to the topic at hand. What could I make to show on African art and the New York avant-garde? How about African art in the Harlem Renaissance?

Though hardly a specialist, I had already made a start with my general knowledge of U.S. history and my research for Creating Black Americans. A Pyrrole-orange flash took me down to Princeton to Marquand Library for research. I discovered a German source for European primitivism, that early-twentieth-century conviction that over-civilization had sapped Europeans’ vitality (often phrased as their virility) and that a remedy lay in art made by non-Europeans deemed “primitive.”

Primitivism conveyed Leo Frobenius’s photographs and drawings and Karl Einstein’s book of African sculpture into the studios of Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Amedeo Modigliani via the Parisian art dealer Paul Guillaume, and from Guillaume to the rich white collector from Pennsylvania, Albert Barnes. In Marquand Library I found the German graphic artist Winold Reiss, illustrator of the Harlem issue of Survey Graphic and The New Negro, and mentor of the quintessential Harlem Renaissance artist Aaron Douglas.

My research revealed that while Alain Locke, a Howard University philosopher and a godfather of the Harlem Renaissance, sought to endow black American art with the ancient pedigree of African art as the “ancestral arts” of African American artists, black artists did not necessarily go along. For one thing, the African art Locke touted was sculpture, while most black American artists of the time were painters. In Marquand I was looking at what artists were actually painting, not merely heeding an idealized theory of the role, in the parlance of the era, of “the Negro artist.”

I paid attention to individual proclivities, going past notions of what black people or black artists represented as an undifferentiated mass. In the work of two pioneering, prizewinning painters, Palmer Hayden and Hale Woodruff, I found art in the tradition of Western art. Woodruff collected African art, but he painted like an American painter of his time. Hayden made one painting on African motifs but said he preferred to paint the people around him, his people. Aaron Douglas’s success in incorporating African motifs, Locke’s “ancestral arts,” appeared as only one way, one of many, of making art while black. In Marquand I found controversy, and I incorporated controversy into illustrations of my talk at the Met.

I loved this work.

I loved the research.

I loved making the art that went with the research.

In my Met presentation I showed my own digital collages along with my art history research. I reworked Winold Reiss’s drawing of Alain Locke to put Locke into a suit (my husband’s), filling in the blank space in Reiss’s portrait to stress Locke’s identity as a sophisticated Howard University professor, as contrasted with “the Negro” working-class figure of the southern migrant to the North. I set Locke in his/Glenn’s suit before Romare Bearden’s The Block, a twentieth-century Harlem scene. I showed Palmer Hayden and Hale Woodruff within their own paintings, which resembled Western painting of their time. I showed Aaron Douglas’s Africanity.

After my Met presentation I continued to work on the images I had created for my talk, elaborating some, jettisoning others. Images too closely tied to the work of illustration fell away. Others survived, becoming an artist’s book I called Art History by Nell Painter Volume XXVII Ancestral Arts. There was no volume XXVI; I began with XXVII. I had it printed at Staples, hence the “Staples Edition.”

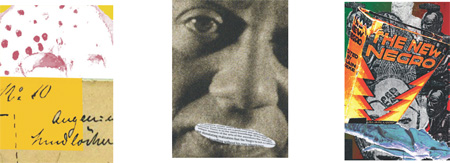

LEFT: Art History by Nell Painter Volume XXVII #10 Frobinius, 2015, digital collage, 48" × 34"

MIDDLE: Locke Ancestral Arts, 2015, digital collage, 48" × 35"

RIGHT: New Negro Stomps Fuller, 2015, digital collage, 48" × 32"

One digital collage began with my reworking and coloring a page of Leo Frobenius’s sketchbook and his drawing of a Congo sculpture. Another inserted Alain Locke’s text on ancestral arts into his mouth in a close-up photographic portrait. Another put together an African piece from Albert Barnes’s collection with the cover of Locke’s The New Negro anthology stomping on a sculpture by Meta Warrick Fuller, an older woman artist whom Locke virtually ignored, even though African imagery inspired her.

A year later I returned to images from Volume XXVII and created new ones from Leo Frobenius’s photographs. The new series became Art History by Nell Painter Volume XXVIII. One of the Palmer Hayden drawings that I had already simplified from the Met talk into Art History by Nell Painter Volume XXVII underwent further alteration. The Volume XXVII version placed Hayden with a looming silhouette of the philanthropist William Harmon in the dark background and Mary Beattie Brady, the administrator of the Harmon Foundation, in the lower right. In Volume XXVIII a fractured image of Brady swamped a fractured Hayden on one page, and on another page, a simplified Hayden repeated in negative in a tint of alizarin crimson and cerulean blue.

Palmer Hayden + Harmon, 2015, digital collage, 48" × 38 ½"

Art History by Nell Painter Volume XXVIII, page 6, 2015, 12" × 12"

and

Art History by Nell Painter Volume XXVIII, page 3, 2015, 12" × 12"

After Volume XXVII, with its cast of characters at the end, text lost its purchase. No such guidance in Volume XXVIII.

Art History by Nell Painter melds history and image in ways that feel right to me and that let me answer the question that Crystal, Laura, and Rob had posed in New Haven. Image lets me concentrate on detail and particularity, on what makes a person or an event or an image unique unto itself. For viewers in search of corroboration—consolation? comfort?—in declarations of community, my stress on singularity can feel wrong, even suspect. An embrace of individual uniqueness can also disappoint the American audience that asks black artists to speak for black people as a whole and to show art whose main role is black identity. To speak to individuality can even seem anti-black within constructions of American identity that equate blackness with community and individuality with whiteness.

In my history books I have already had my say in clear language and discursive meaning about community. Now what history means to me in images is freedom from coherence, clarity, and collective representation. My images carry their own visual meaning, which may or may not explicate history usefully or unequivocally. For me now, image works as particularity, not as generalization. That is how art school changed my thinking about history and how visual art set me free.