9 Pictures of Nothingness

In late 1956, when construction of the first South Pole station was about to get under way, a cartoon appeared in Parade, a widely read U.S. Sunday magazine: it showed a fur-clad expeditioner with a camera, against a uniformly white background shading into blank sky, instructing his subject, another fur-clad expeditioner: ‘Now let’s get one of you standing over there.’1 The cartoon neatly encapsulates the aesthetic problem facing the visual artist at the Pole, at least in the popular imagination: what is there to see?

The continent’s coastal regions and ice-strewn waters, first encountered in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with their impressive icebergs, calving glaciers, plentiful animal life and rocky edges, fitted fairly readily into existing aesthetic approaches, whether these came out of a natural history tradition or the developing conventions of the Picturesque and the Sublime. George Forster, a naturalist on James Cook’s Antarctic circumnavigation in the late eighteenth century, drew on a proto-Romantic aesthetic in his single Antarctic image The Ice Islands, painted in gouache.2 However, the expedition artist, William Hodges, seems to have been underwhelmed, artistically at least, by his Antarctic encounter. While he produced the first paintings of the region – five watercolours – this was far fewer than he created on other legs of the journey, and none of them was later worked up as an oil: ‘One can only assume Hodges did not think the ice of the Antarctic Ocean was a suitable subject for a major painting.’3 Later sea voyages, such as those led by Charles Wilkes and James Clark Ross, generated artworks and illustrations in the naturalistic tradition, ‘bringing the Antarctic coast into the visual imagination of Western civilization without seriously challenging [established] techniques and without suggesting that Antarctica was, for the visual arts, anything unique’.4 Not all Antarctic art of this early period, however, was produced by those who had seen the continent: some of the best-known images of the region were the Gothic illustrations of an 1875 edition of Coleridge’s poem ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, created by the popular French artist Gustave Doré, whose ‘farthest south’ at this point was a tour of Spain.5

|

Since Cook’s time, fewer than 300 visual artists, according to one estimate, have visited Antarctica.6 They have produced a large and varied body of art, including painting and photography in a diverse range of traditions, installation art, sculpture and fine art objects in the form of jewellery, glass and porcelain. Whole books have been written on the topic, and numerous exhibitions held. Most Antarctic art, however, responds to its coastal regions, with more recent artworks engaging particularly with scientific data and climate change. The interior plateau poses its own set of challenges: first, as an artist, how to get there; second, how to work in its conditions; and third, how to develop an artistic language equipped to respond to – or perhaps to challenge stereotypes of – its scale and bareness.

Kirsten Haydon, ice horizon brooch, 2012. Enamel, copper, photo transfer, reflector beads, silver, steel, 80 × 80 × 15 mm.

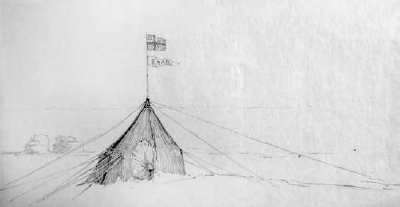

For the first artist to reach the Pole, Scott’s trusted companion Edward Wilson, the first challenge was already moot (returning was the issue); the second he had come to terms with on an earlier, unsuccessful polar journey during the Discovery expedition; and the third would in one sense have been welcome. The problem was that the Pole – the goal of many weeks of struggle and suffering – was not, in fact, bare when Wilson arrived. He thus made sketches of his own forestalment: Amundsen’s black flag, first from a distance and then much closer; a cairn the Norwegian team had left; the tent they had left as a marker. These images joined many he had already made on the polar journey, and would continue to produce on his return. They were found in the polar party’s tent along with the men’s bodies, and a number are reproduced in the first edition of Scott’s journals. As the expedition zoologist, concerned with creating accurate records of his surrounds as much as aesthetic responses, Wilson was highly experienced at sketching in Antarctica. He knew its hazards: the low temperatures would freeze the watercolours he liked to paint in, not to mention exposed fingers, so sketches needed to be made in pencil and worked up later, ideally in the comparative comfort of a hut.7

By Wilson’s time, not only an artist but a photographer was a common inclusion in Antarctic expeditions. Among the continents, Antarctica is unique in that its exploration took place alongside the development of photography and cinematography, meaning that the shots taken of the continent were not preceded by any prior artistic images, indigenous or imported. The oceanographic Challenger expedition (1872–6) captured the first photographs of Antarctic icebergs and a Dundee whaling expedition in 1892–3 took the first of Antarctic land.8 The earliest human settlement of the continent – the huts built by Carsten Borchgrevink’s Southern Cross expedition in 1899 – included a darkroom, and it was this expedition that took the first photograph on the continent: a British flag.9 Photographs had several uses: they served as records of achievements; encoded information about the topography and environment; provided a leisure activity for expeditioners, who sometimes brought their own cameras; and could be used in vital post-expedition publicity, such as newspapers and lectures. Ernest Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition (1907–9) included at least fifteen still cameras – cumbersome but high-quality ones that used glass plates and smaller, more portable ones that took advantage of the newer technology of roll-film.10 Shackleton – who had served as photographer on Scott’s first attempt at the Pole – brought one of the former, along with 36 plates, on his own sledging journey towards the Pole, and it was used to take a photograph of his ‘farthest south’.11 Like the artist, the Antarctic photographer faced numerous challenges in the environment, including the weather conditions, the long periods of darkness during winter, the reaction of the equipment to the cold, the need to wear only one pair of gloves to work the camera, and the long exposure times that required subjects to stay painfully still. These problems meant that photography did not automatically replace art in Antarctica as a means of visual record.12

|

Kirsten Haydon, ice structure brooch, 2011. Enamel, reclaimed steel, photo transfer, silver, 65 × 65 × 12 mm.

Training and equipment from a prominent Norwegian photographer formed part of the preparations for Amundsen’s expedition, but in the end the official camera was damaged and the polar party had to rely on the personal camera belonging to Olav Bjaaland for its visual record of the journey.13 Thus as an image-maker as well as an explorer Wilson was forestalled – by a portable Kodak. On the southward journey Amundsen’s team ‘photographed each other in “picturesque attitudes”’, but the now iconic image shot by Bjaaland shows the team more reverential, hats off, side-on in a rough line beginning with their leader, looking up at their flag.14 This is ‘not merely a picture of someone somewhere’, writes Harald Østgaard Lund, who curates the picture collection at the National Library of Norway: ‘It is the ultimate mental image, the emblem of the proud, independent Norway, stamped, engraved, printed and reprinted again and again in books, magazines and films, on posters, postcards, stamps and packaging material.’ The original negative has disappeared, and many versions – some hand-coloured – exist, with ‘both the flag and Amundsen’s belly’ varying in slackness.15

|

This Norwegian newspaper article from May 1912 boasts the first photographs from Amundsen’s expedition. |

Bjaaland’s photograph of the rest of Amundsen’s team at the South Pole. L–R: Amundsen, Hanssen, Hassel, Wisting. |

|

In the same place a month or so later, while Wilson sketched, Birdie Bowers took photographs, including shots of his companions ranged disconsolately around the same tent. Scott’s men seem dispersed and distracted. The British team took more formally posed shots next to their own flag – all five of them, standing in some versions and sitting in others; the string that Bowers pulled to trigger the shutter is just visible in some reproductions. Having received lessons earlier from the official expedition photographer (the first in Antarctica) Herbert Ponting, Scott himself took many of the photographs on other stages of the journey.16 Ponting was back at the base. He and his heavy equipment could not travel more than the first two days of the journey, and anyway, Scott had reassured him, there would not be much to photograph on the plateau except ‘boundless, featureless ice, with the long caravan stringing out towards the horizon’.17 As it turned out, despite Ponting’s fine photographic record of the expedition, the ‘selfies’ taken by the downcast men at the Pole have become its visual emblem.

Bowers’s photograph of the rest of Scott’s party ranged around Amundsen’s tent. L–R: Scott, Oates, Wilson, Evans. |

|

Amundsen and Scott also brought cinematograph (moving film) cameras, as did other expedition leaders such as Shackleton, Charcot, Mawson, Shirase and even Borchgrevink in the very late nineteenth century. These cameras too could not come on polar journeys. For Amundsen, departing for the Pole, the last sign of civilization was the surreal sight of his endeavour being recorded for posterity: one of the men staying at the base turned the crank of the cinematograph, the machine disappearing below the horizon as the team passed over a ridge.18 Ponting had learned the new technology for Scott’s expedition, and showed numerous versions of the resulting film over his lifetime, to gradually diminishing audiences. His inability to capture the polar journey was significant: the narrative is marred by the gaping hole in its middle, which Ponting could fill only with pre-enactments, illustrations, maps, stills, intertitles and (in the last version) voice-overs. Frank Hurley, another important early Antarctic photographer and cinematographer, suffered a similar problem when Shackleton’s attempt to cross the continent via the Pole (the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–17) went awry before it even reached land. The dramatic footage of the ice-crushed Endurance sinking in the Weddell Sea was some consolation, but Hurley nonetheless appended some footage of animals on the sub-antarctic island of South Georgia, shot on a separate trip, to keep the crowds happy.

|

This illustration from a Norwegian newspaper shows Amundsen lecturing to a large home crowd in September 1912, displaying images from his expedition. |

The Terra Nova expedition photographer Herbert Ponting with telephoto apparatus.

These early images of Antarctica were produced at a time when the artistic world was in transition, moving away from established conventions of visual representation and towards the experimentation, formal abstraction and expression of internal states of mind characteristic of modernism. The seminal discussion of Antarctic art in Stephen Pyne’s The Ice emphasizes the irony that Antarctica’s ‘abstractions, minimalism, and abolished perspective’ failed to engage the modernist artists best equipped to handle these challenges. Modernists’ interest, Pyne notes, was focused elsewhere; additionally, there was the challenge of travelling to the plateau after the ‘Heroic Age’ had waned.19 Anyone wanting immediate experience at the Pole, whether artist or scientist, had to wait for several decades after Wilson had departed.

This hiatus meant that, apart from the aerial survey photographs taken on Richard Byrd’s overflight of 1929 – some of which were reproduced in the expedition account, Little America (1931) – any new visual representations of the Pole in the interim had to borrow from other icy landscapes. The film Scott of the Antarctic (1948) heavily referenced Ponting’s work and included some footage (without actors) taken in the Antarctic Peninsula, but its icy action scenes were shot in Switzerland and (somewhat ironically) Norway.20 The film included a score by the renowned British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, later revised as his Sinfonia antarctica. (Antarctic music – including film scores – has its own substantial history, with contributions by well-known composers such as Peter Maxwell Davies, Nigel Westlake and Ennio Morricone.)

It was only with the establishment of the U.S. base in the later 1950s that visual artists were again able to travel to 90 degrees south. They had to do so as guests of the U.S. military, as there was no other means of travel for those not wanting to sledge across the ice. The first painting produced outdoors at the Pole was by an official Navy artist, 70-year-old Arthur Beaumont. Already accustomed to polar conditions from his artistic assignment in the Arctic, Beaumont stayed at the South Pole station for a week in the summer of 1960–61, working outside by mixing his water-colour paints with torpedo alcohol.21 His South Pole Station shows a surprisingly colourful and crowded Pole, dominated by the radar tracking station for weather balloons, with the stripy ceremonial marker attached to a U.S. flag off-centre in the foreground, and seemingly undulating hills in the distance.

Independent visual artists as well as those officially employed by the Navy travelled to the Pole in its early years of settlement. The Swiss photographer Emil Schulthess spent time at several U.S. Antarctic bases over the 1958–9 summer season, producing a book entitled simply Antarctica (1960). Although unable to visit the Pole, he flew over it, taking aerial shots of the year-old station and the cargo-dropping process. Later, he gave a fish-eye camera to a naval sergeant with instructions to shoot long exposures pointing both up and down at the Pole. The upwards image tracked the path of the sun across the sky: ‘surely’, Schulthess claimed in his book, ‘the first photographic record of the “southern end” of the axis of the earth’.22 For Pyne, Schulthess as photojournalist is a ‘successor to the heroic era’, using new technology to conquer some of the plateau’s challenges without departing from representational art.23

A very different visual artist arrived at the Pole five years later. Sidney Nolan – one of Australia’s best-known painters – spent eight days in the continent together with writer Alan Moorehead as a guest of the U.S. Navy, including a trip to the Pole.24 Nolan’s visit was, according to William L. Fox, the point when modernism arrived on the continent: ‘his paintings of glaciers [are] as much about the flow of his emotions as the ice’.25 Nolan produced 68 paintings (mostly oils) from his time in Antarctica, based on now-missing photographs and watercolours made on site. The first images he produced were landscapes of the coast, conceived as ‘a series of abstract configurations or densely knitted patterns’.26 The Pole itself does not seem to have particularly interested Nolan, except to the extent that it informed the ‘Explorer’ figures that emerge halfway through his Antarctic series. Nolan’s diary indicates that Scott’s polar journey provided the specific inspiration behind Camp, in which two featureless men stand behind a tent with a Union Jack flying, the foreground a mess of shattered ice, the horizon one long grey-white block.27 His generic explorers are ‘vulnerable, isolated, sometimes brutalised. In places they are self-depreciating, ungainly and even slightly comic or absurd.’28 Ironically, Nolan’s modernist images of Antarctica, produced between his paintings of the doomed explorers of the Australian interior Burke and Wills and his famous images of the bushranger Ned Kelly, suggest the continent’s similarity to the Australian desert as much as its alien otherness.29

By the time the influential American landscape photographer Eliot Porter reached the Pole in the mid-1970s, the old station had been replaced by the Dome, and the military by the National Science Foundation. The side-flap of Porter’s collection Antarctica (1978) promises ‘such majestic images as the desolate South Pole’, but in fact he conspicuously avoided the Pole itself, and shows comparatively little interest in the plateau. What for Schulthess was a ‘fascinating endless snowscape’ of which he could not tire was for Porter a ‘dreary landscape’.30 It features in his collection only when punctured by more traditionally spectacular mountains and nunataks. Porter had established his reputation as a wilderness photographer and frames his Antarctic collection in terms of potential environmental threat, describing the myriad ‘predictable consequences of economic exploitation of the last untouched land’.31 For the critic Elena Glasberg, it is Porter’s desire to produce ‘dramatic and anachronistic images of seemingly untouched nature’ that led him to eschew the Pole: ‘within the Porter aesthetic there would be nothing to see there but the significant evidence of U.S. colonization’.32 At the same time, she argues, Porter’s work, which packaged the continent for a U.S. audience in the same visual terms as the American west he had so famously photographed, ‘marked the Antarctic as an object of U.S. concern, and possibly ownership’.33 Where Nolan’s art draws artistic connections with Australian deserts, then, Porter’s joins Antarctica to American landscapes: everyone, it seems, finds their own familiarity within strangeness.

Sidney Nolan, Camp (Captain Scott’s 1912 South Pole Expedition), 1964, oil on hardboard.

For the Minnesotan Stuart Klipper, whose oeuvre displays a horizontal, wide-field and elemental aesthetic, the Antarctic plateau was an obvious fit. Some of his photographs of the far south are collected in his book The Antarctic: From the Circle to the Pole (2008). In his South Pole images, human traces disturb the otherwise confident sweep of the panorama. The Geographic South Pole – an image taken moments after Klipper first arrived at 90 degrees south – shows the familiar sign in the centre foreground dominated by a fluttering U.S. flag (itself cut off by the frame), with a series of marker flags visible in the vague whiteness behind, distracting the viewer from the central object. In Spryte Tracks, the imprint of a vehicle heading out into the faintly sastrugied plateau stops unaccountably just where a shaft of refracted sunlight penetrates the image, so it appears that the aliens so ubiquitous in Antarctic mythology have beamed up the machine. The U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) evidently liked what it saw, because, after an initial trip south with a private sailing expedition, Klipper travelled with the Program to Antarctica five times between 1989 and 2000, making four separate visits to the Pole. Having taken more than 10,000 Antarctic images, Klipper has produced ‘by far the largest and farthest-ranging body of visual work by one person in this area’.34

By the late twentieth century the USAP’s intermittent support of particular artists and writers wishing to travel to the South Pole and its other stations had developed into a systematic programme, minuscule compared to the scientific programme but with its own application process and criteria. While even into the twenty-first century the U.S., like other nations, has tended to send ‘traditional painters or straight-ahead nature and landscape photographers’ south, room opened for more experimental approaches.35 And although the Artists and Writers Program in one sense acts as the ‘cultural wing’ (to use Glasberg’s term36) of broader U.S. activities in the region, effectively excluding projects that are obviously hostile to this effort, work that complicates or resists official discourse and representation nevertheless emerges.

Stuart Klipper, The Geographic South Pole (1989).

One example is the photography of An-My Lê, a political refugee to the U.S. from the Vietnam War best known for her work dealing with war and military activities. Her aim in travelling to Antarctica – she visited McMurdo as well as the Pole – was to look at the role of the military in providing science support (transport and logistics) in the USAP.37 Lê’s approach, however, is a long way from that of the official naval artists and photographers who were part of the program’s early days. Her Events Ashore series, first exhibited in 2008, ‘examine[s] intersecting themes of scientific exploration, military power, environmental crises, fantasies of empire and the vast ungovernable oceans that connect nations and continents’.38 Alongside images of military activity around the globe, Lê placed photographs of Antarctic stations. Works such as Abandoned Dome and Storage Berms at the South Pole ignore the station’s glamorous icons – the Ceremonial Pole, the new state-of-the-art station – in favour of discarded, marginal and utilitarian structures. Her ‘vision of Antarctica’, in Glasberg’s analysis, refuses ‘the overexposed, official view’ of the continent as an exceptional place and instead positions it as ‘a site in the global economy’.39

Most of the South Pole images produced by the Los Angeles photographer Connie Samaras also focus on human infrastructure, although her lines are cleaner and starker than Lê’s, as befitting a project that she entitled (referencing science fiction writer Philip K. Dick) ‘Vast Active Living Intelligence System: Photographing the South Pole’. Samaras has commented that ‘It’s very hard not to go Ansel Adams’ when confronted with the plateau,40 but she resists the urge. Her photographs of the half-finished new station (Samaras visited in 2004) present it in sections rather than as a whole – a series of detached, impenetrable boarded blocks on stilts.41 Samaras’s project was to investigate ‘the liminal space between life support architecture and extreme environment’.42 Underneath Scott-Amundsen Station does this quite literally, showing the area beneath the building designed to be scoured out by wind to prevent accumulating snow – the camera occupies the protective space that separates human artefact from encroaching ice. Samaras’s photographs of the earlier stations, however, ironically inflect this image. In Domes and Tunnels, the NSF station is nearly swallowed by snow drift, and the promise of the brightly lit, glossily red, neatly symmetrical Dome Interior (Samaras mirrored the image) is undermined by the knowledge of its engulfment by ice. The aerially shot Buried Fifties Station shows a few just-discernible marks on the sastrugi-strewn plain. For all its jack-uppable, aerodynamic assurance, the newest station is not the end point of human occupation at the Pole, just the latest in an ongoing expendable series. Samaras felt ‘a poetic relief’ as she ‘observed and documented the geological timeline indifferently erasing attempts to colonize the polar plateau’.43

An-My Lê, Abandoned Dome, South Pole, Antarctica, 2008. Archival pigment print. 101.5 × 143.5 cm |

|

Not all contemporary visual art dealing with the South Pole is created at the South Pole. Anne Noble has travelled to Antarctica three times, on a tourist cruise and with the New Zealand and U.S. national programmes, with the latter including a visit to the Pole. Even before this time, however, the photographs in her Southern Lights exhibition (2005) present Antarctica’s symbolic centre in both playful and telling ways. These are not so much images of the South Pole as images of how humans make images of the South Pole. One shows a CD inscribed with the shape of the continent, a button in the middle labelled ‘push’ marking the place where the South Pole would be. Another offers a close-up of a children’s blow-up globe, with the stopper at the Pole. A third shows a signpost indicating distances from the South Pole to major cities of the world – but the signpost is not at the Pole but in the Fuji Antarctic Museum in Nagoya, Japan. By selling copies of the images on jigsaws and postcards – her Antarctic Collectibles – Noble added another layer to her examination of the way in which representations of the continent are repackaged and circulated.

Connie Samaras, Underneath Amundsen-Scott Station from the exhibition V.A.L.I.S.: Vast Active Living Intelligence System (2005).

Connie Samaras, Dome Interior from the exhibition V.A.L.I.S.: Vast Active Living Intelligence System (2005).

One representation to which artists seem to be repeatedly drawn is the famous set of photographs taken by Bowers at the Pole in 1912. Noble took one of these shots as an inspiration for a ‘re-photographic project’.44 Her series of five images Had We Lived (2012) – photographs of a photograph – present the five men separately rather than together, each seeming to peer through a circle of soft, blurry light, obscured and yet caught in a spotlight. Although they continue to ‘live’ in the circulation of their images, the men in the individual portraits are divorced from both each other and the ‘tale they had to tell’, yet the viewer is invited to read their faces with an intimacy discouraged by the formality of the original shot. In the book/CD collaboration These Rough Notes (2012), which Noble produced together with the composer Norman Meehan and the poet Bill Manhire, these images are juxtaposed with re-photographs of the Erebus air disaster of 1979, which dwarfs in scale and thus recontextualizes the polar tragedy, putting the focus on loss and memory rather than heroism and achievement. The British artist Paul Coldwell, in a series of images produced for his Re-Imagining Scott expedition (2013), also manipulates Bowers’s images as a reflection upon memory and time passing. Coldwell took digital images of Terra Nova photographs – including those from the Pole – and reduced their visual information before printing them out and working on the surface with paint or gouache: ‘My intention was to heighten the sense of surface so the viewer needed to look through this to the photograph beyond … too close and the image becomes unreadable, too far away and the image becomes lost.’45

|

Site-specific art is not easy in Antarctica, because of the weather conditions as well as the limited (if captive) audience, but it does have its own history there, recorded in photographs. In 2007 the Miami artist Xavier Cortada arranged 24 shoes around the Ceremonial Pole as one of a series of installations. Because longitude lines converge at the Pole, the shoes, although in a tight circle, were all at different longitudes. At each shoe, Cortada read a statement from a person affected by climate change elsewhere in the world at the same longitude.46 It is tempting to wonder what the locals made of his efforts; as is sometimes noted in their accounts, writers and artists tend to be considered supernumerary in a place where accommodation is pushed to its limit.

Polies of course produce their own visual responses to place, as evidenced by the innumerable images available on the Internet. Samaras suggests that, given the relatively small number of visitors to the Pole, ‘per capita it may be more photographed than Disney World’.47 Polies also hold their own ‘South Pole International Film Festival’ (SPIFF) to display their efforts, some of which are accessible online, and (like the personnel of other Antarctic stations) they can enter the larger film festival organized by McMurdo base. Unsurprisingly in an environment where outdoor activities are highly constrained, the station includes its own arts and craft room. Occasionally, a home-grown sculpture of sorts will appear, such as the appealing ‘Spoolhenge’: in a postmodern take on ancient astronomy, a series of stacked giant spools – some of which, according to online accounts, originally held the cables (miles long) attached to the IceCube neutrino detectors – became a line of cylindrical menhirs. Local and visiting artistic impulses meet in Noble’s series of photographs of the object, Spoolhenge Antarctica, exhibited in 2008.

Anne Noble, Had We Lived … #2 (Bowers) (2012).

‘Spoolhenge’ in early September 2013: a stack of spools from cables used for the IceCube detector, illuminated from behind by the rising sun with a faint aurora visible on the right.

|

Paul Coldwell, At the Pole I, 2013, ink gouache, enamel onto inkjet, 20 × 28 cm (produced for the exhibition Re-Imagining Scott: Objects and Journeys, Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge). |

While still photography seems to have dominated artistic responses to it in recent years, the Pole is also the subject of numerous films and television documentaries and docudramas. Often it plays a small part in a bigger story: Werner Herzog’s Antarctic documentary Encounters at the End of the World (2007), for example, includes a couple of brief segments at the Pole, which the director regretted was ever reached. ‘At a cultural level’, he reflects, the arrivals of Amundsen and Scott meant ‘the end of adventure’, which thereafter ‘degenerated into absurd quests’. The Pole is the occasional setting of feature films, from the intriguing fictional documentary The Forbidden Quest (1993) to the unremarkable action thriller Whiteout (2009), and of television dramas – a 2008 episode of the hospital series House, evidently influenced by physician Jerri Nielsen’s real-life emergency, features the eponymous medical genius attempting the long-distance diagnosis of a researcher at the Pole. Logistics and expense, however, mean that Antarctic drama is seldom filmed on site.

Visual representations of a place inevitably affect humans’ relationship with that place, no matter how familiar it is from their everyday experience. When it comes to the South Pole, a place comparatively few people have ever directly seen, images become even more potent. The point is made humorously in the novelist Wolcott Gibbs’s satire of the relationship between the press, publicity and polar exploration, Bird Life at the Poles (1931). In the novel the newspaper magnate ‘Mr Herbst’ (read Randolph Hearst) convinces a British explorer to lead an expedition to the South Pole and produce 400 press articles on his return. Before leaving, the explorers pose before a backdrop of snowy mountains borrowed from a Ziegfield ballet set. Questioning whether the image matches ‘the idea people have of the South Pole’, the expedition leader is informed that ‘In this country … people think everything looks the way they see it in the Herbst papers.’ In the twenty-first century most people still have to rely on others’ representations for their visual image of the South Pole, but at least now there is a diverse range from which to choose.