![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Sometimes, when doctors check for cancer, they don’t find it, but they find a condition that may lead to cancer. One such breast abnormality is a condition called atypical hyperplasia, in which there is an overgrowth of worrisome-appearing cells. Atypical hyperplasia is generally thought of as a precancerous condition — it isn’t cancer but women who have it are more likely to develop breast cancer in the future.

Atypical hyperplasia can be further subdivided into atypical ductal hyperplasia — abnormal cells that originate in breast ducts — or atypical lobular hyperplasia — abnormal cells that originate in breast lobules. Another precancerous condition called lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) is generally viewed as a more extensive version of atypical lobular hyperplasia. It’s important to note that while LCIS is called a carcinoma, which means cancer, the exact nature of this condition is still being determined. Most doctors don’t consider it a true cancer.

Researchers have many unanswered questions about atypical hyperplasia and LCIS. For instance, it’s not clear if some precancerous conditions are actual precursors to cancer — the first steps before cancer development — or if they’re cancer markers — indicating an increased risk of breast cancer but not the certainty that cancer will develop.

A woman may receive a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia (atypia) of the breast after a biopsy is done to evaluate a suspicious spot on a mammogram. It can take two forms — atypical ductal hyperplasia (see opposite page) and atypical lobular hyperplasia, which is different in appearance but not in behavior. Neither of these conditions is considered cancerous, but both represent an increased cancer risk.

A woman with either atypical ductal hyperplasia or atypical lobular hyperplasia has about a four times greater risk of developing breast cancer in either breast, compared with a woman who doesn’t have atypia. What does this mean in terms of actual risk? Ten years after a biopsy indicates atypia, about 10 percent of women who receive such a diagnosis will have developed breast cancer; at 15 years, about 15 percent will have developed breast cancer.

And women with atypical ductal hyperplasia and atypical lobular hyperplasia can develop either ductal or lobular breast cancer. In other words, the atypia type doesn’t predict the breast cancer type.

At one time, it was thought that having atypia and a family history of breast cancer meant having an even higher cancer risk, but research has shown that’s not the case. Scientists believe that development of atypical hyperplasia in the breast is the result of some underlying risk — which may be family history in some women and other factors in other women. So the increased risk of breast cancer associated with a woman’s family history has already been factored into the equation when atypia is identified.

When atypical hyperplasia of the breast is found on a needle biopsy, the area is generally treated with surgery to make sure cancer isn’t present. Medication also may be an option following surgery. Breast cancer prevention trials evaluating anti-estrogen medications found that women with atypical hyperplasia who received the drug tamoxifen had a much lower risk of developing breast cancer compared with those women who didn’t receive the drug. Risk was also reduced with the medication raloxifene (Evista), but to a lesser extent.

Chapter 6 has more information on prevention strategies for women considered at high risk of the disease.

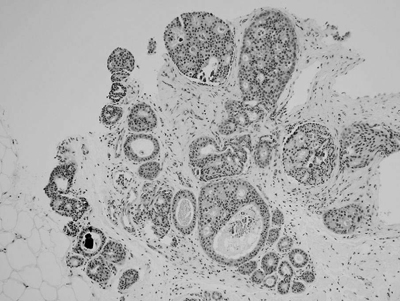

Atypical ductal hyperplasia

The breast ducts seen in this cross-sectional image no longer have a normal, single layer of cells lining them. Instead, there are too many cells that have an abnormal (atypical) appearance. The dark black spot in the lower left indicates calcification of debris that’s collected within the duct.

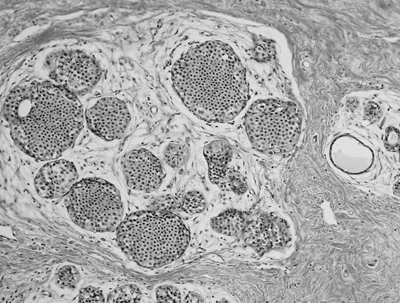

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)

This image shows breast lobules filled with cells that are abnormal (atypical) appearing. A biopsy sample in which similar but less extensive changes were involved would be called atypical lobular hyperplasia.

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) is thought to develop within the lobules located at the end of the breast ducts (see opposite page). LCIS usually doesn’t show up on mammograms but may be found in breast biopsies done for other reasons.

Over the years, most cancer experts haven’t considered LCIS to be cancer in and of itself. Rather, they viewed it as an area of abnormal tissue growth that signals an increased risk of developing invasive breast cancer later on in either breast.

Unlike ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), discussed in the next chapter, LCIS is much less common. And because it’s less common, there hasn’t been as much good research on the condition to determine its long-term cancer risk. It’s often said that a woman with LCIS has about a 20 to 25 percent risk of developing invasive breast cancer in either breast over her lifetime, but the data supporting this estimate are relatively weak. In comparison, the lifetime risk of breast cancer for women in general — those who haven’t been diagnosed with LCIS — is around 12 percent.

In deciding how to treat atypia and LCIS, a number of factors are taken into account, including personal choice.

Watchful waiting

Given the relatively low likelihood of developing invasive breast cancer in the first few years after being diagnosed with these conditions, some women choose the option of close monitoring. This generally involves yearly screening mammograms, monthly breast self-examinations and regular clinical breast exams.

This approach works best in women who have breasts that are relatively easy to examine by clinical examination and mammography, as opposed to women who have lumpy breasts or women whose breast tissue appears very dense on mammograms.

Other women prefer to take preventive measures to reduce their cancer risk. Options include taking cancer-preventing medications or, less commonly, surgically removing both breasts.

Cancer-preventing medications

Two selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) drugs are approved to reduce the risk of invasive breast cancer.

One of those medications is tamoxifen. It can be used by both premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Tamoxifen is typically taken for five years. Raloxifene (Evista) also is approved to reduce the risk of invasive breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women, including those with atypical hyperplasia or LCIS.

Another type of medication called exemestane (Aromasin) also has been shown to reduce the risk of invasive breast cancer. Exemestane is a type of medication known as an aromatase inhibitor.

These medications do carry some side effects, so the benefits of the drugs need to be weighed against their unwanted effects.

Preventive surgery

Preventive surgery (bilateral prophylactic mastectomy) isn’t usually performed in women with atypical hyperplasia. However, it may be considered for women with LCIS.

To obtain the best possible protective benefit from this surgery, both breasts are removed, because LCIS increases your risk of developing breast cancer in either breast. However, there’s debate as to whether removing both breasts is justified, considering the majority of women with LCIS won’t develop breast cancer.

Ultimately, it’s a personal choice, based on a thorough discussion with your doctor. Treatment of LCIS isn’t urgent, so you have time to carefully weigh the pros and cons of the procedure.

To learn more about breast cancer prevention strategies, see Chapter 6.