![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Decreased Arm and Shoulder Mobility

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Relief for night sweats and sleep disturbances

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cancer treatment can save or extend lives. But being treated for cancer also presents a number of challenges — from side effects such as fatigue and nausea, to the ongoing stress of doing battle with a life-threatening disease, to changes in home or work responsibilities.

In this chapter, we look at some of the physical challenges you may face during your treatment, and the emotional stress that often accompanies them. We also discuss ways to help you cope with common treatment side effects. The chapter begins with those challenges most often associated with the treatment of relatively early-stage breast cancer. Later on, you’ll find information on some of the physical challenges associated with more advanced cancer.

When most people think of cancer treatment, often the first things that come to mind are nausea and hair loss. Fatigue, though, is probably the most common side effect of cancer treatment — not just of treatment but of cancer itself. In part, fatigue is a reaction to the physical and emotional toll that cancer takes. It can be one of the most debilitating side effects, interfering with everyday activities, including working and spending time with family and friends.

For individuals who haven’t experienced cancer-related fatigue, it can be difficult to grasp what it’s like. Everyone knows what it feels like to run out of steam after a hectic day, but a little rest usually helps you bounce back. Cancer-related fatigue is more encompassing, and rest may not make it better.

How people with cancer experience of fatigue can be different. Descriptions include feeling exhausted, being worn out, running on empty, feeling weak, having heavy limbs or having absolutely no energy.

Causes of fatigue

No one knows all of the causes of cancer-related fatigue, but we do know that certain conditions can contribute to it. Cancer specialists from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network have identified the following conditions as having a significant effect on fatigue:

If you’re experiencing cancer-related fatigue, talk with a member of your health care team. You should be evaluated for anemia and possibly low thyroid function. If you’re anemic, treatment may include taking iron supplements. For severe symptoms, you may need a blood transfusion. Injections of the synthetic hormone erythropoietin, given to stimulate the production of red blood cells, are no longer used because they may increase your risk of blood clots and stimulate cancer growth.

Low thyroid function isn’t a common side effect from cancer treatment unless you received radiation therapy to your neck. However, it’s a fairly common condition, caused by a number of diseases. Standard treatment for an underactive thyroid involves taking a synthetic thyroid hormone on a daily basis. This oral medication restores hormone levels to normal, easing fatigue.

Other factors that may contribute to your fatigue include medications you may be taking, such as pain relievers or antidepressants, other medical problems, poor nutrition, and inactivity. Be sure your health care team knows of any prescription or over-the-counter medications you’re taking. If poor nutrition is a problem, your doctor may refer you to a registered dietitian, who can help you understand your nutritional needs. For fatigue caused by inactivity, simply getting out and walking — even for just a few minutes — can help.

Accepting your limits

Ignoring your fatigue and pushing yourself too hard may make your fatigue worse. Many people highly value their independence, and needing to ask others for help is a new and unwanted experience. But it’s important to accept that you can’t do it all. Call on friends and family to help with chores and errands.

In a few instances, fatigue may last for years. During the first year after cancer treatment, fatigue is one of the most common complaints.

Self-help strategies

Resting or sleeping more doesn’t “cure” fatigue resulting from cancer treatment, but you can do things to help minimize it:

If fatigue remains a problem, ask your doctor about other therapies that may help you. Over the years, doctors have explored the use of medications to reduce cancer-related fatigue. Most of the drugs studied have been psychostimulant medications. To date, the drugs haven’t been found to reduce fatigue by a measurable amount and they carry side effects.

Some herbal medications may reduce fatigue by a small amount without the side effects of prescription medications (see Chapter 21).

Eating healthy foods while undergoing cancer treatment is good for you. They can help you feel better and maintain your strength. But eating well can sometimes be difficult because cancer treatment can cause nausea, vomiting and changes in how food tastes, which may affect your appetite. There are ways to avoid or reduce these problems.

Nausea medications

Much progress has been made in development of medications that prevent and control the nausea and vomiting that accompany cancer treatment. Anti-nausea medications (anti-emetics) are routinely given before your chemotherapy treatment begins, as a preventive measure.

Chemotherapy drugs typically are rated on a scale of how likely they are to cause nausea. For drugs that tend to cause little nausea, you may not need anti-nausea medicines, or your doctor may recommend a drug such as prochlorperazine, commonly used to treat nausea resulting from a number of causes.

If your chemotherapy treatment involves medications that are more likely to cause significant nausea and vomiting, your doctor may prescribe a corticosteroid medication and one of the newer anti-nausea drugs, such as ondansetron (Zofran), granisetron, dolasetron (Anzemet) or palonosetron (Aloxi). You may takes these with another medication to control nausea and vomiting called aprepitant (Emend).

You take these medications before chemotherapy and sometimes after your treatment, as well. To boost their effectiveness, these medications may be prescribed with other anti-nausea drugs. Side effects of some anti-nausea drugs include drowsiness and constipation.

If you’re taking an anti-nausea drug and still experiencing nausea, talk to your doctor. Together you can try to find a combination of medications to better control your symptoms.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

During chemotherapy treatment, it’s best to avoid foods that are overly sweet, fried, spicy or fatty because they’re more likely to trigger nausea. Foods that are cool or at room temperature may be more appealing because they produce less of an odor than do hot foods.

You may want to cook and freeze meals before your treatment or have someone else prepare your food when you’re not around to smell the cooking odors. Easily digested foods include crackers, dry toast, broth and broth-based soups (such as chicken noodle), hard candy, frozen fruit bars, and flavored gelatin. If you tolerate those, try other mild-flavored, low-fat foods, such as cereals, rice, plain noodles, baked potatoes, lean meats, fish, chicken, cottage cheese, fruits and vegetables.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Self-help strategies

In addition to medications, some self-help strategies may help:

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

After one or more chemotherapy treatments, some people develop a reaction by which they get nauseated and vomit before chemotherapy treatment. The nausea is triggered by something connected to the treatment, such as pulling into the hospital parking lot, walking into the chemotherapy suite or smelling an alcohol swab.

This is called anticipatory nausea, and up to half of all cancer patients who undergo chemotherapy may experience this.

Chances that you’ll experience anticipatory nausea are greater if:

Unfortunately, standard anti-nausea drugs typically aren’t very effective for anticipatory nausea and vomiting. Anti-anxiety medications, such as lorazepam (Ativan), may help a bit. Relaxation techniques and behavior modification techniques, which teach you to remain calm and relaxed when you encounter whatever triggers your nausea, also may help.

If you experience anticipatory nausea and vomiting, tell this to a member of your health care team.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Appetite and weight changes

Cancer treatment can have two effects on your appetite and weight. It may make you lose your appetite, and thereby lose weight, at a time in your life when getting the proper nutrients may be more important than ever. Alternatively, chemotherapy can cause unwanted weight gain in some women.

Weight loss

Once you begin treatment, you may find that food may not taste the way it did before your treatments. You also may have difficulty chewing or swallowing, or your mouth may be dry. Distress, anxiety or depression also can cause you to lose your appetite.

If you’re not hungry or interested in food, don’t force yourself to eat, but do try to get enough nutrients. Here are some suggestions you can try to help make sure you’re getting adequate nutrition:

If you’re having trouble chewing or swallowing, try eating soft foods, such as scrambled eggs, milkshakes, applesauce and mashed potatoes. If you’re choking on your food or coughing it back up during or after your meal, tell your doctor. If your mouth is dry, sip on water, unsweetened juice and other fluids throughout the day. Try eating soups, drinking milkshakes and consuming other foods that have a high liquid content.

Maintaining your weight can be a sign that you’re eating enough. If you’re losing weight and you need to increase the amount of calories you consume, try consuming more high-calorie foods and beverages, such as peanut butter, nuts, ice cream, malts, ice cream floats, milkshakes, nutritional drinks and eggnog. To increase protein and calories, add fortified dry milk to your beverages. Talk to your doctor if you’ve lost 5 or more pounds. He or she might recommend a medication to help stimulate your appetite.

Unwanted weight gain

A few decades back, it became apparent that many women tended to gain weight following a diagnosis of breast cancer, and that weight gain was more prevalent in women who received chemotherapy. There probably are multiple causes for this weight gain:

What can you do if you start to gain weight when you don’t want to? In general, two common-sense steps can lead to weight loss: First, try to reduce your daily calories either by eating less or by reducing the amount of fat in your diet. Second, develop a routine exercise program to increase your level of physical activity.

If you’re still having trouble losing weight, talk with your doctor about making an appointment with a dietitian or enrolling in a weight or exercise program.

On the upside, weight gain associated with chemotherapy is becoming less of a problem than it used to be. This is likely related to increased awareness of the potential for weight gain during treatment, better counseling by doctors and nurses, and shorter durations of chemotherapy medications.

Many people who’ve been through cancer treatment will say that the most distressing part of their treatment was losing their hair (alopecia). In addition to the change in your physical appearance, hair loss is a very public banner that says, “I have cancer.”

Hair loss is most often associated with chemotherapy treatment. The drugs work by destroying rapidly growing cancer cells in the body. But in addition to cancer cells, they attack other rapidly growing cells, such as those that make up your hair follicles. The result is hair loss.

Hair loss from chemotherapy medications depends on the type of drugs used, as well as an individual’s response to the medications. Some women lose all of the hair on their heads in addition to their eyebrows and eyelashes. Others experience only hair thinning, and still others have no hair loss.

If you’re going to lose your hair, it’ll likely begin to shed 10 to 20 days after you begin chemotherapy treatment. Your hair may come out gradually or in clumps. Some women report scalp tenderness when their hair falls out. Keep in mind that your hair should grow back after treatment ends. In fact, it may grow back thicker than it was before you began chemotherapy. For some women, their hair starts to grow back before they finish treatment. It’s not uncommon for the new hair to be different in color or texture.

Radiation therapy to the head also can cause hair loss. Unfortunately, if your hair loss is due to radiation, it may not grow back completely because the hair follicles may be permanently damaged.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

In the 1980s, researchers had an idea for preventing hair loss that involved placing ice caps on the scalp prior to and during chemotherapy treatment. Their thinking was that the ice would cause blood vessels in the scalp to constrict so that less chemotherapy could get to the scalp, resulting in less hair loss. The procedure, known as scalp cryotherapy, didn’t work very well, and there was concern that it could potentially allow cancer cells in the scalp to grow.

In recent years, this procedure has made a comeback. Better means of applying cold to the scalp have been developed, and studies suggest the chance of cancer growing in the scalp is extremely low. Scalp cryotherapy is being used to varying degrees in various medical centers. It’s still quite cumbersome and it can be uncomfortable. With time, better means of preventing hair loss will likely be developed.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Self-help strategies

Your doctor or another member of your health care team can tell you if the chemotherapy drugs you’ll be taking are likely to cause hair loss, which gives you time to make some decisions beforehand. You may opt for a wig or plan to wear hats, turbans or scarves to cover your head. Or you may decide to leave your head bare. It’s likely you’ll choose different alternatives in different situations, such as when staying home or going to a social function. There’s no right or wrong choice. Base your decision on what makes you feel most comfortable.

If you plan to wear a wig, consider getting it while you still have your own hair. That way, the wig maker can match it to the color and texture of your hair. Some shops specialize in creating wigs for women with cancer. To find out if such a shop is in your area, ask a member of your health care team, check the Yellow Pages or call your local American Cancer Society chapter. Many insurance companies will help pay for a wig if you have a prescription for one from your doctor.

When your hair begins to fall out, treat your remaining hair gently. Use a mild shampoo, brush it gently with a soft brush and set your blow-dryer on low heat. Don’t color, perm or chemically relax your hair. Use a satin pillowcase when you sleep because it won’t tug on your hair the way a cotton or synthetic pillowcase might.

Some women opt to shave their heads when their hair starts falling out. If you choose to do so, have someone help you and be careful not to nick your scalp, which could lead to an infection. Be sure to apply sunscreen or wear a hat to protect your head from the sun, and cover your head when it’s cold outside to protect against loss of body heat.

Talking with your health care team about your distress over losing your hair may help you manage your feelings.

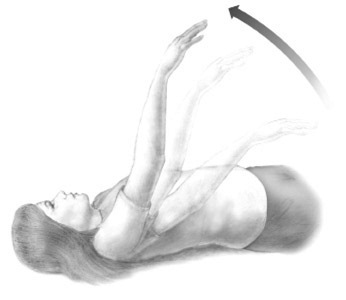

A common concern for women who’ve had surgery for breast cancer is regaining arm and shoulder mobility. Depending on the type of surgery you’ve had, the arm and shoulder adjacent to the breast that underwent surgery may be stiff and sore for a time. Limited movement of the arm and shoulder is most often associated with removal of lymph nodes from under the arm during surgery.

Because of the discomfort, you might be inclined to protect your arm by keeping it still and not using it. But that’s not a good idea. Lack of movement can make your arm even weaker, and it can make your arm and shoulder less mobile.

Breast cancer surgery most often affects the type of arm and shoulder movement that you use when you reach upward (abduction), such as when you lift a brush to your hair. This type of movement is used in many everyday tasks, such as driving, retrieving an item from a shelf, and putting on a shirt or coat.

After breast cancer surgery, women typically are given instructions on exercises they can do at home to regain function of the affected arm and shoulder. If you haven’t received such instructions, ask for them. Exercising is generally recommended once all surgical drains are removed.

Interestingly, one study found that women who participated in a physical therapy program to regain arm and shoulder mobility achieved better shoulder motion than did women who were just given an instructional booklet after surgery. You might ask your health care team about enrolling in a physical therapy program, and if you’re able, find a physical therapist skilled at working with women recovering from breast cancer surgery.

Below are some some basic exercises that you can do yourself. The most important thing is to get your arm and shoulder moving.

Take it easy

Inactivity following surgery can cause your arm, shoulder and upper chest muscles to become stiff and weak. When you first begin your exercises, it’s important to start slowly.

Gently stretching your arm and shoulder muscles will help lessen the stiffness and the feeling of weakness. This gentle movement is the key to maintaining arm and shoulder function.

The exercises shown provide the gentle stretching necessary to keep your arm and shoulder mobile.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Arm raises

Lie on your back in bed with your arms at your sides. Slowly raise your affected arm straight above your head to stretch the muscles. Lower and repeat. If it would be helpful, fold your hands together and use your unaffected arm to help lift your affected arm.

Deep breathing

Sit in a straight-backed chair and breathe deeply in and out to expand your chest muscles.

Shoulder rotations

Sit in a straight-backed chair. Gently rotate your shoulders forward, down, back and around in a smooth, circular motion to loosen your chest, shoulders and upper back muscles.

Hand squeezes

Using an object such as a rubber ball or washcloth, make a fist and squeeze tightly. Repeat several times throughout the day to strengthen your arm.

NOTE: The following exercises are a bit more strenuous. If you’ve had breast reconstruction, wait at least four weeks after surgery to do these.

Wall climb

1. Stand facing a wall, with your toes as close to the wall as possible and your feet shoulder-width apart.

2. Bending your elbows slightly, place both your palms against the wall at shoulder level.

3. Using your fingers, work your hands up the wall — “walk up the wall” — until your arms are fully extended.

4. Work your hands back down to the starting point.

Arm swing

1. With your unaffected arm, hold onto the back of a sturdy chair.

2. Let your affected arm hang in a relaxed position.

3. Swing your affected arm from left to right. Be sure to move your arm from your shoulder, not your elbow.

4. Swing your affected arm in small circles, again making sure the movement comes from your shoulder. As your arm relaxes, the size of the circle will probably increase. Then circle in the opposite direction.

5. Swing your affected arm forward and backward from your shoulder, within your range of comfort.

Pulley

1. Obtain a rope-and-pulley system. These are usually available at medical supply stores and hardware stores. Fasten the system to an overhead beam. Over-the-door models also are available.

2. Sit or stand with the pulley overhead but slightly behind you.

3. Grasp one end of the rope with the hand of your affected arm, or let your hand rest in a loop tied at the end of the rope. Grasp the other end of the rope with the hand of your unaffected arm.

4. With the elbow of your affected arm slightly bent, slowly raise your affected arm forward and upward by gently pulling down on the rope with your other arm.

5. Stop the motion when you feel a pinch, but before you feel any pain in your shoulder.

6. Hold for 10 seconds. Then using the pulley, slowly lower your affected arm to your side.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Surgery, radiation therapy or other cancer treatment that involves removal of or damage to your lymph nodes may cause you to retain lymph fluid in the area where the lymph nodes were damaged or removed. When this happens, your arms or legs can swell, a condition called lymphedema. Edema is a medical term that means “swollen.”

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped structures found throughout your body, about 350 to 500 of them in total. They produce and store infection-fighting white blood cells, called lymphocytes. Lymphocytes are distributed through your body by way of your blood vessels and also through a network of vessels called lymphatic channels. These vessels carry a clear liquid known as lymph fluid from the tissues of your body to larger lymph vessels, which eventually empty into a large vein in your upper chest, just before the vein brings blood back to your heart.

Surgery or radiation therapy for cancer often results in removal of or damage to lymph nodes and lymph vessels. If your remaining lymph vessels can’t maintain the proper flow of lymph fluid, excess fluid can back up and accumulate in the affected limb, causing swelling.

Signs and symptoms include:

If you were treated for breast cancer and you had radiation therapy or had your underarm lymph nodes surgically removed or both, you’re at risk of lymphedema in the arm on that side.

Sometimes, lymphedema occurs right after surgery and is mild and short-lived. At other times, it becomes a chronic problem. It might first occur months or years after treatment. The condition generally isn’t painful, but it can be uncomfortable, due to the heavy feeling it causes in the affected limb.

Reducing your risk

There are no scientifically proven ways to prevent lymphedema, but most doctors believe you can do certain things to reduce your risk. Keep in mind, though, that the following suggestions need to be considered in the perspective of trying to live a full and active life.

Try to avoid infection

Your body responds to infection by making extra fluid to fight it. If your lymphatic system isn’t operating to its full potential because of cancer treatment, this extra fluid can build up, triggering lymphedema. To avoid infection:

Try to avoid burns

Like infections, burns can lead to excess fluid in women whose lymph nodes and vessels have been damaged or removed. To avoid burns:

Other tips

You can also reduce your risk of lymphedema by:

![]()

QUESTION & ANSWER

Q: Can lymphedema be treated with medication?

A: In the early 1990s, researchers published a study in The New England Journal of Medicine reporting that a medication called coumarin (not related to coumadin, the drug used to treat blood clots) effectively reduced lymphedema in a variety of people. Most of the participants in the study had lymphedema for reasons other than cancer treatment.

To follow up, Mayo Clinic researchers developed a clinical trial to evaluate the use of coumarin in women with lymphedema resulting from breast cancer treatment.

Unfortunately, results of this study, which included 150 women, found no benefit in taking coumarin. In fact, a few women receiving the drug developed liver toxicity, a condition that may be life-threatening.

Presently, there isn’t a medication known to effectively treat lymphedema.

Treating lymphedema

Fortunately, lymphedema is less of a problem today than it was previously. Use of the sentinel node biopsy procedure (see sentinel node biopsy) has reduced the need for removal of the underarm (axillary) lymph nodes during breast cancer surgery.

Despite your best efforts to prevent it, lymphedema can still become a problem when lymph nodes are removed. If you do experience arm swelling, early intervention is key. It’s easier to keep the swelling from getting worse than it is to reverse it once it has advanced.

The most common way of managing lymphedema is to wrap the affected arm or leg with elastic bandages and, once the swelling is reduced, to wear a compression sleeve or stocking, which is a special garment made of elastic material.

There’s considerable debate about the best way to get fluid out of the limb. Some doctors prescribe various compression pumps to try to help the fluid flow out of the affected arm or leg. These pumps often put pressure on the furthermost part of the arm or leg and try to milk the fluid toward the heart. There’s some concern that this might put too much pressure on already-compromised lymphatic vessels, making the problem worse.

Some doctors suggest massage as a better means of getting the fluid out of the limb. The massage begins at the hand, working the fluid out of this area, and then proceeds up the limb, helping to get the fluid out in a stepwise fashion. Some massage therapy treatments include extensive daily therapy over two weeks. Other times, the treatments are done periodically for an indefinite period of time.

If you’re seeking treatment for lymphedema, your best bet is to visit a medical facility that has staff with extensive experience in treating the condition. The doctors and therapists there can help decrease the amount of lymphedema in your limb, teach you how to keep the fluid under control, and provide appropriately fitted elastic sleeves and stockings and ongoing therapeutic recommendations. Look for medical centers that have specialized lymphedema clinics.

To keep fluid from reaccumulating, exercise the affected arm regularly. Women who had axillary lymph node removal as part of breast cancer surgery were once told to avoid exercising the affected arm, due to concerns that the movement and stretching might lead to swelling. However, studies have found just the opposite — that use of arm muscles helps return excess fluid into circulation.

Menopause occurs naturally in women at midlife. It begins when your ovaries start making less of the hormones estrogen and progesterone, which regulate your monthly ovulation and menstruation cycles. Eventually — when hormone production ceases — your ovaries don’t release any more eggs, and your menstrual periods stop. Certain surgical or medical treatments for cancer can bring on menopause earlier than it would normally occur, which is generally about age 51.

A hysterectomy that removes your uterus but not your ovaries doesn’t cause menopause. Although you no longer have periods, your ovaries still produce hormones. However, an operation that removes both your uterus and ovaries (total hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy) does cause menopause. If you’re premenopausal, your periods stop immediately and you’re likely to have hot flashes and other menopausal signs and symptoms. This is known as surgical menopause.

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the pelvis also may induce premature menopause. In addition, many of the hormone treatments for breast cancer can cause menopausal signs and symptoms. Premenopausal women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer may experience a relatively abrupt decline in ovarian function. The effects of sudden menopause are often more intense than are those of natural menopause. Unlike the more gradual hormonal changes of natural menopause, which usually occur over several years, hormone changes associated with surgical menopause are abrupt, often making the signs and symptoms more intense. Premature menopause also puts you at risk of other conditions, such as the bone-thinning disease osteoporosis.

Effects of sudden menopause

The signs and symptoms of menopause can range from mildly uncomfortable to severe. Some women experience several signs and symptoms, and others experience few, if any. The most common are hot flashes, sleep disturbances, night sweats, vaginal changes and emotional changes.

Hot flashes

Reduced estrogen in your bloodstream can cause abnormal regulation of your blood vessels, causing your skin temperature to rise. This can lead to a feeling of warmth that moves upward from your chest to your shoulders, neck and head. You may sweat, then feel chilled as the sweat evaporates. You may also feel slightly faint. Your face might look flushed, and red blotches may appear on your chest, neck and arms.

Sleep disturbances and night sweats

Hot flashes during the night can lead to night sweats. You may awaken from a sound sleep with your sleepwear and bed linens soaking wet, which may then cause you to feel chilled. In addition, you may have difficulty falling back to sleep, preventing you from achieving a deep, restful sleep.

Vaginal changes

Lack of estrogen can cause the tissues lining your vagina to become drier, thinner and less elastic. Decreased lubrication may cause burning or itching and may lead to increased infections of the vagina and urinary tract. These changes may make sexual intercourse uncomfortable or even painful.

Emotional changes

You may experience mood swings, be more irritable or be more prone to emotional upset. In the past, these symptoms were attributed to hormonal fluctuations. But the stress of having cancer and other life events understandably may contribute to changes in your mood, too.

Relief for hot flashes

If you’re bothered by hot flashes, a combination of self-help strategies and medication often can reduce their severity.

Self-help strategies

Most hot flashes last from 30 seconds to several minutes, although they can last much longer. The frequency and duration of hot flashes vary from woman to woman. You may experience them once every hour, or you may be bothered by them only occasionally.

If you’re experiencing hot flashes fairly regularly:

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Loss of fertility is a possibility for some younger women who undergo cancer treatment that produces menopause. Infertility may be related to surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

If you were planning to have children, loss of fertility can be devastating. Some women experience grief and loss similar to that after the death of a loved one. When your friends and family members become pregnant, you may feel jealous and resentful — and then guilty for feeling that way. (See "If you still want to have Children" for information on ways to preserve your ability to have children before starting cancer treatment.)

Even women who weren’t planning to have any more children may feel some grief at becoming infertile. They may feel they’re less whole or less feminine.

To cope with infertility caused by cancer treatment:

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Medications

A variety of medications may reduce the effects of hot flashes. Discuss your options with your doctor, to determine what’s right for you.

Hormone therapy

The most established treatment for hot flashes is the hormone estrogen, used in hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Estrogen reduces hot flashes by up to 90 percent. The hormone progesterone also can reduce hot flashes to a similar degree. However, because breast cancer and some gynecologic cancers are fueled by hormones, oncologists are often reluctant to prescribe HRT, and many women are reluctant to take hormones.

Vitamin E

Research suggests that taking 800 international units of vitamin E a day reduces hot flashes a little bit more than does taking a placebo. What does that mean? In many clinical studies, women who took a sugar pill (placebo) daily reported about a 25 percent reduction in hot flashes after four weeks. Women receiving vitamin E reported about a 35 percent reduction in hot flashes four weeks later.

Clonidine

Clonidine (Catapres), a pill or patch developed to treat high blood pressure, also may help alleviate hot flashes to some degree. It does, however, have side effects, such as dry mouth, sleep disturbance, dizziness, drowsiness, lightheadedness and constipation, so doctors don’t prescribe it as often as other remedies for hot flashes.

Antidepressants

Some antidepressant medications have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing hot flashes. Research indicates that a low dose of venlafaxine decreases hot flashes by about 40 percent. A slightly higher dose decreases hot flashes by about 60 percent. Venlafaxine is well tolerated by most women, although a few women taking it experience significant nausea or vomiting. For some women, the initial nausea goes away after a few days, despite continued drug use.

Venlafaxine has other side effects, such as mild dry mouth, decreased appetite and some constipation. If you have uncontrolled high blood pressure, your doctor may not recommend this drug because it may increase your blood pressure.

Other antidepressants also appear to relieve hot flashes. Medications such as paroxetine (Paxil) and citalopram (Celexa) appear to work as well as venlafaxine. Fluoxetine (Prozac) also may reduce hot flashes, but not as well as other anti-depressants.

Anti-seizure medications such as gabapentin (Neurontin) and pregabalin (Lyrica) have been shown to reduce hot flashes. These medications can produce side effects such as lightheadedness and mild swelling, which some women find more bothersome than those associated with venlafaxine.

Relief for night sweats and sleep disturbances

Night sweats are usually the nighttime equivalent of hot flashes. You may awaken from a sound sleep soaked in sweat, followed by chills. You may have difficulty falling back to sleep or achieving a deep, restful sleep. Lack of sleep may affect your mood and overall health. If you experience night sweats or have trouble sleeping, try the following strategies:

Relief for vaginal dryness

As your estrogen level declines, the tissues lining your vagina and the opening to your bladder (urethra) become drier, thinner and less elastic. With decreased lubrication, you may experience burning or itching, increased risk of vaginal or urinary tract infections, and discomfort during intercourse.

For vaginal dryness:

If these measures don’t work, you might ask your doctor about vaginal estrogen replacement therapy. Because vaginal dryness results when your ovaries no longer produce estrogen, vaginal estrogen therapy can help relieve signs and symptoms. Vaginal therapy increases the amount of estrogen in the vagina, helping to relieve vaginal dryness.

Although doctors may be concerned about prescribing estrogen treatment in pill form to women with breast cancer, in some cases they may feel it’s reasonable to use local estrogen treatment, such as a vaginal cream, to treat vaginal dryness (see “Concerns About Vaginal Estrogen”).

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Over the years, there has been much debate about the use of vaginal estrogen therapy. Most doctors and cancer survivors opt against oral estrogen therapy because of concerns about increased estrogen in the bloodstream and associated breast cancer risk. With vaginal estrogen therapy, a small amount of estrogen is absorbed and enters the bloodstream. Theoretically, this could cause some concern. However, many oncologists and gynecologists believe that breast cancer risk associated with vaginal estrogen use is likely very small.

Vaginal estrogen therapy is a reasonable choice for controlling vaginal signs and symptoms associated with cancer treatment. If you’re concerned about possible cancer risk from the therapy, it’s OK not to use it.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Vaginal estrogen preparations

Vaginal estrogen cream (Premarin, Estrace, others) can help relieve vaginal dryness and itching. You insert the cream into your vagina with an applicator, daily for five to seven days. You can continue using it one to two times a week to control symptoms.

A vaginal estrogen ring (Estring) is a soft, plastic ring that you or your doctor insert into the upper part of your vagina. The ring slowly releases estrogen over a period of 90 days.

Vaginal estrogen also comes in the form of a tablet (Vagifem). You use a disposable applicator to regularly place a tablet in your vagina — every day for the first two weeks and then twice a week.

All of these methods increase the amount of estrogen in your vagina and should relieve vaginal dryness for as long as you use them.

Cautions

Virtually all vaginal estrogen preparations appear to get absorbed and travel to other parts of your body to some degree. One situation when it doesn’t make sense to use a vaginal estrogen preparation is if a woman is taking an aromatase inhibitor. This type of medication is designed to decrease the body’s estrogen to as low a level as possible. It’s more reasonable to use vaginal estrogen treatment if you’re receiving tamoxifen or if you have an estrogen receptor negative cancer.

Talk to your doctor about whether estrogen treatment is an option and, if so, which type might work best for you.

After treatment for cancer, your sex life may be affected in a number of ways. Studies have shown that about 25 to 35 percent of women diagnosed with breast cancer experience some type of sexual dysfunction.

Sexual changes that women may experience after cancer treatment include painful intercourse, difficulty reaching orgasm and decreased interest in sex.

Talk with your doctor or another member of your health care team if you’re experiencing sexually related problems. Often, sexual problems can be treated.

Painful intercourse

Painful intercourse is a common sexual complaint after cancer treatment. The medical term for this problem is dyspareunia. It’s most often caused by estrogen loss that leads to vaginal dryness. Chemotherapy and hormone therapy can, in part, lead to sexual problems by decreasing estrogen.

Fortunately, there are things you can do to help make intercourse less painful:

If your doctor recommends a vaginal dilator to stretch your vagina, use it as directed. Vaginal dilators are latex, plastic or rubber cylinders that are made in a variety of sizes. They’re lubricated and inserted into the vagina and left in place for about 10 to 15 minutes at a time, three times a week or every other day.

![]()

QUESTION & ANSWER

Q: What is vaginismus?

A: Painful intercourse, whether caused by vaginal dryness, vaginal stenosis or a shortened vagina, can sometimes trigger a condition called vaginismus. The muscles around the vaginal opening become clenched in a spasm. With vaginismus, a woman’s partner can’t enter the vagina with his penis. The harder he pushes, the greater her pain becomes.

Difficulty reaching orgasm

Almost all women who are able to reach orgasm before cancer treatment continue to do so afterward. However, you may find that the steps necessary for you to become sexually aroused have changed. For instance, if a part of foreplay was stroking sensitive areas that have since been affected by cancer treatment, such as your breasts, you may need to find new areas that provoke sexual arousal when touched.

To help yourself reach orgasm, talk to your partner and make sure your partner knows which types of touch excite you. You might even have a sexual fantasy during lovemaking to distract you from negative thoughts.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Kegel exercises can help you learn how to tense and relax your pelvic floor muscles, which may help lessen discomfort during intercourse. To do Kegel exercises, contract the muscles you use to stop urine flow, hold for a count of three, and then relax. Repeat 10 to 20 times, a couple of times a day. If you’re feeling pain during intercourse, stop and take a moment to relax your pelvic floor muscles.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Decreased interest in sex

Just as cancer treatment causes physical changes, it often packs an emotional wallop, too. You may experience several different feelings after cancer treatment or, perhaps, just a few.

A common problem following cancer treatment is loss of desire for sexual activity (libido). You may lose interest in sex for many reasons. It may be because of all the changes you’re going through. You may be recovering from surgery, radiation therapy or chemotherapy, and perhaps you’re tired or you don’t feel well. Chemotherapy and other medications can disrupt your hormone balance, reducing your sex drive.

You may be fearful, anxious or depressed. These are common responses to a life-threatening illness. Many people find that their fears decrease with time and their libido improves. But for some, the emotional distress becomes overwhelming and medical intervention becomes necessary. Some medications used to treat depression and anxiety can interfere with your sex drive.

You may also have concerns about how your body has been altered by cancer treatment and whether your partner still finds you sexually desirable.

Women who have a mastectomy are particularly vulnerable to this problem. For both women and men, the breast represents a significant aspect of sexuality. Removing an entire breast (mastectomy) or changing its look and feel (lumpectomy) can alter a woman’s perception of herself as a sexual being. According to some researchers, mastectomy leads to more post-cancer sexual problems than do many other treatments.

If you have a loss of interest in sex, and if it concerns you, try these suggestions:

Talk with your partner

One of the best ways to improve sexual intimacy is to open the lines of communication. For example, your partner may think you’ve lost interest. You may believe your partner isn’t interested in you. A conversation about the issue can clear the air and restore emotional and physical intimacy. Begin by telling your partner how you feel about your sex life and what you would like to change. Explain why you think your sex life is the way it is and how it makes you feel. Avoid blame, and try to stay positive.

Set aside time for romance

When you’re ready, make a date with your partner. Create a sensual mood using lighting, music and fragrance. Go slowly at first, focusing on foreplay. Slowly reacquaint yourself with your partner. Sometimes agreeing not to include intercourse can help you relax and focus on pleasurable activities.

Focus on new ways to make yourself feel sensual and attractive. Try a new haircut or color. Buy some beautiful new pajamas or a nightgown to help you feel more desirable.

Talk with your doctor

Sexual problems may not improve on their own. If you’re having troubles and your doctor or another member of your health care team hasn’t discussed sexual issues with you, take the lead. Your doctor can help determine if you need a referral to a specialist or, perhaps, suggest new ways to express sexual intimacy. If you’re going to discuss your sex drive with your doctor, you might want your partner to attend the appointment, too. Having your partner with you will ensure that both of you receive the same information.

![]()

QUESTION & ANSWER

Q: I’ve heard that testosterone may increase a woman’s libido. Is this true?

A: Evidence suggests that decreased sexual desire in women may be related to lowered concentrations of the hormone testosterone. Women’s bodies do normally produce small concentrations of this male-associated hormone. After menopause, the levels are reduced. The administration of testosterone has been studied as a potential treatment for decreased libido. Some studies suggest it may be beneficial, especially when given to women who still have some estrogen in their bodies (premenopausal or taking estrogen replacement). However, most evidence suggests that it’s not helpful for postmenopausal women with a history of breast cancer.

As more women survive cancer, the long-term effects of cancer treatment on bone health are becoming more apparent.

Osteoporosis is a condition in which your bones become brittle and weak, leading to an increased risk of fractures. Women who’ve been treated for cancer are at increased risk of osteoporosis for several reasons. Some breast cancer treatments inhibit bone formation. And medications used to control some of the side effects of chemotherapy, such as steroids, can lead to bone loss. In some cases, the cancer itself may cause bone loss.

Cancer treatment can also have indirect effects on bone loss. Aromatase inhibitor medications decrease estrogen concentrations in your blood, and this leads to bone loss. Surgical removal of the ovaries — sometimes a part of treatment for breast cancer — initiates immediate menopause. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy for cancer also may cause the ovaries to stop functioning. During the first few years after this occurs, you lose calcium from your bones at a much faster rate than normal, increasing your risk of osteoporosis.

Prevention and treatment

Several options are available for preventing and treating osteoporosis.

Calcium and vitamin D

Two of the most straightforward, highly recommended strategies are to get adequate calcium and vitamin D and to take part in weight-bearing exercises. Women at risk of osteoporosis should aim for 1,500 to 2,000 milligrams a day of calcium and 400 to 800 international units of vitamin D. The calcium and vitamin D can be from food sources or from supplements.

Exercise

Weight-bearing exercise can be as simple as walking and jogging. Non-weight-bearing activities, such as swimming, are helpful for general fitness, but they’re not adequate for maintaining bone strength.

Estrogen

Estrogen therapy has been shown to be useful in preventing bone loss. However, given concerns about its use in women who’ve survived breast cancer, other options are more frequently recommended for these women.

Raloxifene

Raloxifene (Evista), a medication somewhat similar to the cancer drug tamoxifen, is taken to help maintain bone strength. It may also decrease breast cancer risk. However, there’s some concern about prescribing raloxifene for women who’ve already taken tamoxifen for five years. Therefore, raloxifene generally isn’t recommended for breast cancer survivors who’ve had tamoxifen. Raloxifene also may cause hot flashes.

Bisphosphonates

Medications known as bisphosphonates also can help preserve bone strength. These drugs appear to be as effective as estrogen in terms of promoting bone health. Bisphosphonates currently on the market include alendronate (Fosamax), risedronate (Actonel) and ibandronate (Boniva). You take these medications either once a day, once a week or once a month in a larger dose. Bisphosphonates should be taken first thing in the morning, on an empty stomach. Be sure to avoid lying down for at least 30 minutes afterward to avoid acid reflux into the esophagus.

Zoledronic acid (Zometa) is another form of bisphosphonate. It’s different in that it’s an intravenous medication, meaning it’s administered by injecting the drug into a vein. Evidence suggests that receiving intravenous doses of this drug at six- or 12-month intervals may help maintain bone strength.

Denosumab

Denosumab (Prolia) is a newer type of osteoporosis drug. It’s a type of antibody treatment that works in a different way but produces similar or better results, compared with bisphosphonates. Denosumab is delivered via a shot under the skin every six months. This same medication is also used to prevent bone complications from metastatic breast cancer. When used for cancer treatment, the medication is known as Xgeva.

Calcitonin

Calcitonin is an intranasal medication taken as an inhalant. It’s another option for reducing bone loss in women with osteoporosis, but it’s not as effective as bisphosphonates.

Some chemotherapy medications can cause nerve damage (neuropathy), which can result in poorly defined pain throughout the body and in numbness and tingling in the feet and hands. Taxane drugs, such as paclitaxel, used in the treatment of breast cancer are most commonly associated with neuropathy.

Some women who receive chemotherapy medications don’t experience any problems with neuropathy. In others, it can become a substantial problem. New research suggests people affected by neuropathy may have a genetic makeup that predisposes them to these problems.

Acute pain syndrome

Taxane medications can cause a type of pain syndrome which peaks about three to four days after receiving the medication and then disappears a few days later. The pain is located throughout the body and it can be difficult to define — likely because most women have never had nerve pain like it before.

Women receiving lower, more frequent doses of taxane medications usually have less of a problem than do women who are given the drugs less often and in higher amounts. In recent years, the trend has been to administer taxane medications in smaller doses more often — weekly instead of every three weeks.

Peripheral neuropathy

Another side effect of some chemotherapy medications is peripheral neuropathy. It’s a problem that affects the far (peripheral) extremities — the feet and hands. Often, the feet are affected more than the hands.

Peripheral neuropathy tends to become apparent the longer taxane medications are taken. Initially, symptoms include numbness and tingling in the hands and feet, which can make it difficult to button a button or manipulate small objects. Sometimes the symptoms will remain mild. Other times, they may worsen, and in addition to the numbness and tingling, sharp, shooting or burning pains may develop in the extremities. If the symptoms become too severe, the medication is generally stopped and replaced with a different type of chemotherapy drug.

Unlike acute pain syndrome, symptoms of peripheral neuropathy generally don’t improve in between treatments, but they often get better once chemotherapy treatment is complete. Unfortunately, a few people experience symptoms for years after their treatment is complete.

There’s no way to prevent chemotherapy-induced neuropathy other than to reduce or stop the medication. Sometimes prescription medications may be used to relieve pain associated with the condition.

In addition to nerve pain, some medications taken to treat breast cancer can cause aches and pains in the joints.

Post-chemotherapy rheumatism

Some women who undergo chemotherapy as part of treatment for their cancers develop pain and stiffness in their muscles and joints, typically one to two months after completing treatment. This condition, which appears to be triggered by chemotherapy medications, is called post-chemotherapy rheumatism. Doctors estimate the condition may affect up to 5 percent of women who receive a combination of chemotherapy medications.

The most common complaint of post-chemotherapy rheumatism is stiffness in the morning or after periods of inactivity. The hips and knees are most often affected. In most cases, symptoms of post-chemotherapy rheumatism go away without treatment, usually within six to 12 months. Researchers theorize that the condition may be a type of withdrawal from chemotherapy. Many questions about this condition remain unanswered.

Over-the-counter pain relievers haven’t been found to provide much relief for this condition. But there are some things you can do that might help. If you’re experiencing musculoskeletal pain after cancer treatment, avoid long periods of sitting. If you must sit for a long time, reposition yourself often to prevent or lessen stiffness. Turn your head at different angles, shift the position of your arms, and bend and stretch your legs. These slight movements may help prevent excessive stiffness. If you’re able, get up and walk from time to time.

Aromatase inhibitor arthralgias

About half the women who take aromatase inhibitors experience joint aches and pains. The symptoms may be new or they may be a worsening of joint aches and pains that existed before your cancer was diagnosed. For mild symptoms, over-the-counter pain relievers may help. In severe cases, an aromatase inhibitor may have to be stopped. After a few weeks to a couple of months, your doctor may recommend that you try another aromatase inhibitor to see if the problem still persists. Sometimes a different medication is more tolerable than the first one.

As discussed earlier, some cancer survivors who’ve received chemotherapy drugs or are taking certain hormone medications have problems with weight gain. Unfortunately, in many cases, the extra weight stays on even when treatment ends.

Some studies suggest that weight gain is greater among premenopausal women treated for breast cancer than among women who’ve already gone through menopause. This could be because chemotherapy causes premature menopause in younger women, and menopause often is accompanied by weight gain. Women who were postmenopausal when treated for cancer may have already gained the weight associated with the onset of menopause.

Some women also report weight gain while taking the drug tamoxifen. However, about an equal number of women report experiencing weight loss. Again, weight gain associated with tamoxifen may have more to do with a woman’s age than with the medication. Women tend to gain weight when going through menopause, and breast cancer — and the treatment that follows — is often diagnosed around the age when women start to experience menopausal symptoms.

Reducing your risk

Most doctors point to exercise as the best way to prevent or minimize weight gain after cancer treatment. In addition to helping you lose weight, exercise helps reduce fatigue, insomnia and anxiety, all of which can be consequences of cancer diagnosis and treatment.

If you’ve found that you’ve lost muscle and gained fatty tissue in your arms and shoulders during your treatment, you may find strength training exercises for your upper body to be helpful. Strength training exercises for your legs may be helpful, too.

Talk with your doctor about starting an exercise regimen that includes both aerobic exercise and strength training. And ask for a referral to a dietitian who can help you develop a healthy diet that won’t add extra pounds.

Some people treated for cancer report having problems with memory or concentration after receiving chemotherapy or radiation. Studies suggest that people who’ve been treated with chemotherapy are at greater risk of having such problems. Higher doses of chemotherapy seem to lead to greater problems. However, even people who receive standard doses can report memory or concentration difficulties. This problem is known as cognitive dysfunction and has been labeled by some as “chemo brain” or “cancer brain.”

Most women who receive chemotherapy don’t experience significant cognitive changes following their treatment, and they continue to effectively perform complex mental tasks.

The exact cause of cognitive changes and the degree to which they affect people aren’t clear. Using radiologic imaging techniques, researchers have been able to visualize brain changes in women who received chemotherapy. They hope that within a few years — when more results of current research become available — they’ll have a better understanding of the situation.

People who talk about the cognitive effects of cancer treatment tend to describe a blunting of their mental sharpness, fuzziness in dealing with numbers, trouble finding the right word and short-term memory lapses. Some people report changes in memory or concentration beginning sometime during cancer treatment. Others report symptoms sometime after their treatment ended.

At this time, there are no ways to prevent cognitive changes from chemotherapy. But there are some things you can do that can help you manage the situation:

If you’re really bothered by your symptoms, talk to your doctor.

![]()

Shirley Ruedy and her husband, George, In Washington, D.C., for a national breast cancer awareness luncheon.

Shirley’s Story

Shirley Ruedy has stared breast cancer in the face not once, but twice. The first time she was 43. The second time — 15 years to the day after her first diagnosis — she was 58. The first time was a terrible blow. The second diagnosis “felt like a comet hitting the earth.” Instead of a cancer-free anniversary celebration, Shirley sat in her doctor’s office coming to grips with a nightmare of every cancer survivor — another cancer.

Unlike the first cancer, which was caught early, the second one was more advanced. It had spread to a lymph node and her chest wall. Shirley underwent a second mastectomy, followed by six rounds of chemotherapy and 35 radiation treatments. It has now been about 17 years since her second breast cancer, and each day that Shirley wakes up, she knows that she’s fortunate to be alive. She tries to live life to the fullest, not dwelling on the past or worrying about the future.

“I figure you do everything you absolutely can, and then you forget about it. I don’t think that God has given you another chance at life to live it in misery. Worrying about it all the time is hellacious.”

Shirley Ruedy knows cancer well — too well. She cared for her mother as her mother died a slow, agonizing death from colon cancer. She watched as her brother endured repeated treatments for breast cancer, until the cancer took his life. And she has stood by as good friends have received diagnoses similar to hers, and some haven’t been as fortunate.

Shirley also knows cancer well because it became her life’s work. Sometime after her first experience with breast cancer, Shirley returned to her writing career, accepting a job at the local newspaper in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. She proposed a regular column on cancer, feeling readers wanted, and could benefit from, more cancer information. For many years, until her recent retirement, Shirley wrote her award-winning “Cancer Update,” a platform for anything to do with cancer. She shared the latest information on cancer screening and treatment. She encouraged readers to be proactive — to get second opinions, to challenge doctors if they felt it necessary, and to take steps to reduce their cancer risk. She also exposed the emotional side of cancer: common fears, feelings and frustrations.

Some of Shirley’s most touching and popular columns were those in which she reflected on her own cancer battles and those of dear friends — putting into words the weighty surge of emotions in the power struggle between life and death.

Shirley Ruedy knows cancer well, but it’s her sincere hope that future generations won’t have to.

Here’s one of Shirley’s columns.

It’s so good to feel good

By Shirley Ruedy

Gazette columnist

It’s been a year.

A very mottled year. In a way, it seems like a lifetime since I was told, one stunning Tuesday, that the breast cancer which had beat its drum so loudly in my life 15 years ago, dying to a dim sound in the distance, now beat violently once again.

It was back, they said. A brand new one. A new one to lick, to contend with, to watch its shadow, to sleep, it seemed, with one eye open.

And in another way, it’s impossible to believe that a whole year has gone by. To think how innocently I tripped into last November, thinking of the holidays, thinking of finishing the work on our newly refurbished kitchen — certainly not thinking of another cancerous visit.

So busy was I that I forgot the follow-up appointment I had made with the oncologist for that funny “blip” on my rib. After a reminder call, I went blithely off; after all, the tests had been negative so far, right?

Ah, yes. So much for the “best laid plans of mice and men.” Once again you are brought to your knees, made to recall that puny humankind has no firm grasp on the reins of life. What looks so leather-sturdy is as a dream, and you wake up holding only gossamer strands.

For that is, after all, all that life is: The most delicate thread (not the rope we fancy) tethering us to a final life — and we become so caught in our daily rushing about that we forget that at any given moment, the tether can reel us in to our eternal destination.

That is what I was abruptly reminded of last November. And I recalled that once there is the precedence of cancer cells in your body, in the family, one has to be forever the watchful sentinel.

REFLECTIONS: I did not have chemotherapy or radiation with my first mastectomy, as many readers know. So the “chemo” I began on Jan. 3, 1995, was a brand new world to me. My regimen, as I noted before, was not the most severe ever given, nor the lightest. I did what most of you would do: I endured, I prevailed, and I am here.

As I look back, what was most interesting, in light of the fear that so many people have worked up on the subject of chemotherapy, was simply, the chemotherapy suite.

It was, really, human nature at its best: Duty, love, compassion. The people —young, old, short, tall, fat, thin, rich, poor, men, women, white, black, brown, yellow — showed up dutifully at their appointed times. They marched like soldiers to recliner chairs or beds (their choice), sitting or lying there quietly. They thought ... or read ... or talked with companions.

The patients were on the front line, but those steadfast companions were right at their sides — husbands, wives, parents, adult children or friends, loyally accompanying their beleaguered loved ones through the weeks and months of therapy. They never asked for credit, they never sought attention, they were just there: Love aflower, love abloom, love majestic.

Mostly, it was quiet in the rooms. Whatever fears, wishes or apologies that were tucked away in the corners of souls — well, they had already been talked about before going there. Or, perhaps the thoughts would stay in their niches, never to come out. But everyone, patient and companion alike, knew why they were there. This was The Big Time. This was The Fight of Their Lives.

There was, of course, the silent drip-drip-drip of the IV — man trying anew to arrest one of the world’s oldest diseases. The nurses went in and out, swiftly performing the mechanics of their trade, sometimes sensing a flagging spirit, sitting down to dispense some soft words of encouragement.

I learned that chemicals can teach you a lot about humans.

It’s so good to feel good again, to see the hair on my head again. Do you want to hear something funny? It’s curly! It’s just a stitch! Little curls racing around my neckline. At times, I felt like the chemo was enough to curl my toes, but instead, it curled my hair.

Shirley Temple reincarnated! Wheeeee! Let a new year ring!

Reprinted with permission © 1995 The Gazette, Cedar Rapids, Iowa

![]()