![]()

![]()

When You and Your Family Disagree

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Appetite changes and weight loss

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

When breast cancer reaches an advanced stage, there comes a point when many women realize the time has come to stop treating the cancer. Perhaps you’re facing such a situation.

The decision to stop treatment aimed at killing the cancer (anti-cancer therapy) is generally considered after a woman and her doctor have discussed all of the remaining options, and they’ve determined that:

If this is your situation, your decision to stop anti-cancer therapy is both a logical and an understandable one. Now, instead of trying to kill the cancer or slow its progression, the goals of your treatment are to:

It’s important to remember that just because you’re stopping treatment aimed at fighting the cancer doesn’t mean you’re ending your medical care. You’ll continue to receive regular care from your doctor.

In the beginning, right after receiving your diagnosis, the emphasis of treatment typically is on curing the cancer. If the cancer isn’t curable, treatments are used to slow the growth of the tumor in an attempt to allow you to live longer. When efforts to slow cancer growth are no longer effective, the emphasis shifts primarily to alleviating discomfort and other symptoms. This is known as supportive (palliative) care (see Palliative Care). Supportive care also includes addressing any of your psychological, social, spiritual and emotional needs, as well as providing support for your family.

How do you know when the time has come to stop fighting the cancer? It’s a difficult decision to make. It’s a personal decision that only you can make with advice from your health care team, family and friends. Some women find it difficult to end treatment aimed at destroying or controlling the cancer because it feels like they’re giving up. But if the cancer has become resistant to anti-cancer therapies, such treatments may do more harm than good. For many women, the quality of their lives becomes paramount because they want to enjoy the time they have left.

The time when you may fare better without anti-cancer therapy arrives when the therapy stops working and the downsides of continuing it outweigh the potential benefits. For example, for many people with cancer, there eventually comes a time when the chances that chemotherapy will make them sick — and maybe cause potentially life-threatening side effects — may be far greater than the chances of it shrinking the cancer.

Deciding to stop anti-cancer treatment that’s no longer helping you may be a way for you to take back control. You may feel as if your life has been out of control since you learned that you have cancer. Making the decision to stop cancer treatment and to be free of the side effects of treatment can be a powerful step in taking charge of your life.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Many people with a terminal illness want their doctors to tell them how much time they have left. This is a hard question for doctors to answer, and many may be reluctant to respond to it directly. For one thing, they can make only an educated guess. For another, answering the question requires a difficult balance between being realistic and hoping for the best.

Because doctors can’t help becoming personally connected to their patients and their patients’ families, they may overestimate prognosis in order to maintain hope. This could mean you may not have as much time as your doctor says you do.

Independent of trying to maintain hope, a doctor may simply be wrong in his or her estimate of the manner and speed in which the cancer will progress. Multiple studies have demonstrated that doctors tend to be overly optimistic regarding life expectancy in people with advanced cancer.

If your doctor does give you a time estimate, don’t take it as gospel. Some people live longer than their doctors thought they would, others live less.

Having a time estimate may help you feel more in control, but no matter how much time you may have left, make the best of it. Live each day as fully as possible, doing the things you want to do.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Even as you accept that your cancer isn’t curable, you can still have hope. But your hopes might change as your circumstances change. For example, when you first received your diagnosis, you may have hoped that it was a mistake. Once you accepted the diagnosis, you undoubtedly hoped to beat the cancer. When you learned the cancer wasn’t curable, you may have hoped that your treatment would work well enough to extend your life for several years.

So what do you hope for now that you realize further attempts at controlling the cancer likely won’t work? That depends on your goals. This may be a time to reframe your hopes. They may include spending quality time with family, taking a trip, relieving your symptoms or living in comfort, without pain and suffering. Perhaps your hope centers on leaving a legacy for your children or grandchildren. This might involve putting your financial affairs in order, videotaping or writing family stories, or creating a document in which you write about your values, the lessons you’ve learned from life, and your love for family and friends.

Keep in mind, though, as you set your goals, that cancer’s path can be difficult to predict. The course of your cancer can change abruptly, and it may not be possible for you to meet all the goals you’ve set. Some people think of it this way: Hope for the best while you plan for the worst. Make time to take care of responsibilities and essentials. Sign papers you need to sign, tell friends and loved ones what you want to say to them, and write down whatever thoughts you need to express in writing.

It’s fine to have some longer term projects on your list of goals, but you may also want to be sure that you have a goal for each day, such as reaching out to friends and family or writing notes to people who have touched your life. In Gayle's Story, you can read the notes one mother wrote to her sons as she was in the later stages of her cancer.

Most people don’t want to discuss dying. But rather than approach the subject with fear, why not treat this as a time to think about living and dying with the idea of compassion and kindness for yourself and your family. If you’re interested in finding some peace for yourself, you might consider a couple of these ideas:

Keep in mind that some of your loved ones will feel a strong need to express their feelings at this time, and others won’t feel capable of that. This can be a beautiful time of sharing, and you are the one with the most control over this opportunity. When you’re ready, you and loved ones can share many simple but important words. These may include simple phrases such as: “I love you,” “I forgive you,” “I’m sorry,” “Thank you” and — when the time is appropriate — “Goodbye.”

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Some people with advanced cancer find it difficult, if not impossible, to accept that their treatments are no longer working and that their cancers are terminal. They may employ a defense mechanism known as denial.

Denial may be either harmful or beneficial. It’s beneficial when it enables you to process information about your illness in your own time and in such a way that you can absorb it without being overwhelmed. But continued denial can cause you to insist on receiving anti-cancer treatments when it’s clear they’re no longer beneficial, and more importantly, it can keep you from getting your affairs in order, saying your goodbyes and, ultimately, dying a peaceful death.

In a study of people with advanced lung cancer, individuals who had difficulty accepting their eventual death and who continued to receive aggressive treatment didn’t live any longer than those who stopped their anti-cancer therapy earlier.

Denial can be especially problematic if your family can’t accept your illness and encourages or reinforces your denial. If you or family members are having a difficult time accepting that your cancer is terminal, it may help to talk with a counselor, chaplain, hospice worker or member of your health care team. An opportunity to express your fears, which can contribute to denial, may help you approach your illness more realistically so that you can make informed decisions regarding your future.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Your illness affects your entire family. When you, along with your health care team, make the transition from anti-cancer treatment to supportive care, your family members may not understand. They may say that you’re giving up. Maybe it’s your spouse or your children or a relative who comes from out of town who hasn’t been involved with your illness and treatment who wants you to “keep fighting.”

Throughout your illness, you have experienced many losses. Although difficult, each loss may have caused you to establish new goals and to redefine hope. These losses, in some ways, prepare you for death. While your family members have experienced some degree of loss, too, it’s different from your own. They may not be ready to let you go.

As you face the last phase of your illness, the support you receive from family and friends can influence how well you cope. If your goals are at odds with those of family members, arrange a meeting with them and members of your health care team. Ask someone from your health care team to explain your situation so that your family understands the basis for your decision and to answer questions family members may have.

Be firm in your resolve to do what’s best for you. Don’t be pressured to accept treatment just to keep the peace. That may do you more harm than good. Tell your loved ones that what’s most important to you now is being able to enjoy high-quality time with them.

It’s natural for people with incurable cancer to fear pain and other symptoms the disease may cause. Once you stop treatment intended to kill or slow the cancer, that doesn’t mean your care will end. Your health care team will still take care of you, helping you manage your symptoms and other conditions that may arise. The goal is to help you live as comfortably as possible. Many approaches can be used to manage symptoms and conditions that may develop. Depending on your situation, your primary care doctor or oncologist may enlist the help of an individual who specializes in supportive care.

Pain

Pain can be a major factor in your ability to enjoy life. It can affect your sleeping, eating and other day-to-day activities. For people with advanced cancer, pain is usually caused by the cancer spreading into organs, bone or soft tissue or by the cancer pressing on a nerve. Pain that involves an organ may be difficult to pinpoint and may be described as a dull, deep throbbing or aching or, occasionally, as sharp. Pain that involves skin, muscle or bone is usually limited to a specific area and may be described as sharp, aching, burning or throbbing. Pain that involves nerves (neuropathic pain) is often described as sharp, tingling, burning or shooting.

Pain may be severe but last a relatively short time (acute pain), or it may range from mild to severe and persist for a long time (chronic pain). Certain pain may also be associated with specific movements or activities and may be predictable (incident pain). There’s also a type of pain known as breakthrough pain. It occurs when moderate to severe pain “breaks through” the medication that’s controlling it. Breakthrough pain usually lasts a short time but may occur up to several times a day.

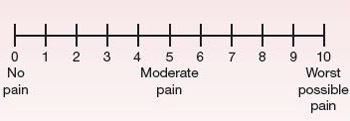

You will likely be asked to rate your pain on several occasions. This is so that your health care team can provide you with the right dosage of medication to keep on top of your pain — to control it adequately, but not provide you with so much medication that you have difficulty functioning.

For some people, rating their pain is a difficult thing to do. People’s perception of pain is different, and what one person may consider mild another person may rate as severe. Still, your input is important. It’s easier for your doctor to manage your pain with some input from you, than with none at all.

Using a pain scale can help your doctor determine how much pain you’re in and measure how well your treatments are working. You rate your pain from 0 to 10. A rating of 1 to 3 generally means mild pain, while 7 or above indicates severe pain.

Seeing your doctor

Many medications can effectively manage pain, but your doctor needs to know the specifics of your pain to be able to treat it. To help your doctor assess your pain, provide him or her with as much information as possible, including the answers to the following questions:

It might help to keep a written record of your pain so that you can give your doctor an accurate report. Besides answering the questions above, keep track of your pain medication and the effect it has on your pain, and for how long. Let your doctor know if the medication is causing unwanted side effects, such as interfering with your activities or your ability to sleep or eat.

To assess your pain, your doctor will likely perform a physical examination and may request some tests, such as blood tests or X-rays, to determine the cause.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Studies have shown that many people with cancer are reluctant to take strong pain medications, such as opioids (narcotics), for two reasons. They’re afraid of becoming addicted to the medications, and they’re afraid that if they use strong medication too early in the course of their disease, it won’t work for them later when their pain becomes more severe. These fears are understandable, but neither of them has a medical basis.

Addiction is a type of behavior where a person compulsively seeks drugs for the mental high they might provide. When opioid medications are used to treat cancer pain, addiction to these drugs is rare.

For people who take opioids for a long time, though, it’s common for them to develop tolerance to a drug. With tolerance, the effects of the drug decrease with regular use, and the person taking the drug may need higher doses to achieve the same effect. Fortunately, doses of these drugs can be increased. There’s no maximum dose that can be given (“ceiling effect”). Therefore, if you become tolerant of a certain dose, your doctor can increase the dose until your pain is relieved or prescribe a different medication.

In addition, your body may become used to receiving the drug at regular intervals, a condition called physical dependence. If you stop taking it abruptly, you may experience withdrawal. Withdrawal can be avoided by slowly tapering off the drug if it’s no longer needed. It’s important to know that tolerance and physical dependence are not the same as addiction.

Tell your doctor about any problems with pain medication you’ve had in the past. Follow directions for taking your medication. And let your doctor know if it isn’t providing enough relief.

Pain management is vital to maintaining a good quality of life. Cancer pain may require strong medications such as opiods. Work with your doctor to find the medication or combination of medications that works. Don’t let fear of addiction keep you from getting relief from your pain. Ask your doctor to refer you to a pain specialist if needed.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Treatment

The primary goal is to treat the source of the pain, if possible. This may include use of treatments such as radiation, surgery and targeted medication. With advanced cancer, though, it’s not always possible to treat the specific cause. Then treatment typically involves use of analgesic pain medications, which range from simple pain relievers to opioids, also known as narcotics.

Simple pain relievers include acetaminophen (Tylenol, others), aspirin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen (Aleve). Steroid medications also may be helpful in some situations. Opioids, the strongest pain-relieving medications, include codeine, oxycodone (OxyContin, Roxicodone, others), morphine, fentanyl (Duragesic) and hydromorphone (Dilaudid), among others. For severe pain, opioids are the best medications. Sometimes, regular doses of aspirin, acetaminophen or ibuprofen may be recommended in addition to an opioid medication to boost pain relief.

Opioids can be either long-acting or short-acting, referring to the period of time that they remain active in your system. Generally speaking, short-acting medications take effect quickly — within 30 to 60 minutes — and provide relief for up to two to four hours. Long-acting opioids, on the other hand, may take several hours to reach peak effectiveness, but their effects generally continue for about 12 hours.

For some people on long-acting opioids, taking an intermittent short-acting opioid can help relieve breakthrough pain that arises between scheduled doses of the long-acting drug. If you’re experiencing breakthrough pain, a rapid-onset, short-acting opioid in addition to your long-acting medication should give you relief. If you know from experience that a particular activity triggers the pain, taking a short-acting opioid beforehand may block or significantly diminish the pain.

If you have continued pain, it’s best to keep the pain under control by taking your pain medication at regular intervals rather than intermittently or as needed. This is especially true for the strong opioids. Steady dosing may diminish the side effects of the medication. Taking your medications on a regular schedule also provides better and more even pain control, and you actually may end up needing less medication than if you take the drugs intermittently.

Opioid medications may be given orally, by way of patches placed on the skin, by rectal suppositories or by injection.

Another method of receiving medication is by way of a pain pump. A pain pump can be implanted under the skin of your lower abdomen with a small tube placed in the spinal canal next to the spinal cord, where pain signals get transmitted to your brain. Though delivered to your spinal cord, the medication may help eliminate pain elsewhere in your body. Your doctor may suggest this method if you have severe pain that isn’t controlled with regular opioids or if you’re experiencing excessive side effects from the medication that can’t be controlled.

Opioid medications may cause side effects such as drowsiness, dizziness, nausea and confusion. Most of these side effects are easily managed and, with steady dosing, they often diminish after a few days. One of the most common side effects is constipation. This occurs in almost all individuals who take opioid medications on a regular basis. Generally, only with appropriate treatment, does the condition improve. Your doctor will likely start you on a regimen of stool softeners or bowel stimulants or both, as soon as you begin taking an opioid. It may be easier to prevent constipation than to treat it.

Other medications may be useful for specific types of pain. Anti-seizure drugs or other related medications may be helpful in individuals who have nerve damage. Medications called bisphosphonates that are used to treat osteoporosis may be helpful if you’re experiencing pain from bone damage due to the tumor. Your doctor also may suggest other means of pain control, such as nerve blocks by injections of chemicals or radiation therapy to a localized area of pain.

If you find the side effects of a drug intolerable, if your medication isn’t working well enough or long enough, or if you have frequent breakthrough pain, you may need to try another medication or other pain control methods.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Stress and anxiety can make your pain worse by creating tension in your body. Techniques designed to help relieve anxiety and help you relax may also help control your pain. These include deep-breathing exercises, meditation and progressive relaxation. See Chapter 21 for more information on relaxation techniques.

In addition, try to get your mind off your pain by doing activities that you enjoy, such as listening to music or engaging in a hobby. If you’re able, exercise may make you feel better and help you relax and sleep. Try to get some exercise daily, even if you only feel well enough to walk for a few minutes on the arm of a family member or friend.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Shortness of breath

Another condition that can occur is shortness of breath (dyspnea). It has multiple causes, including cancer spreading to the lungs, heart problems, muscle weakness, anemia and generalized fatigue. At times, the underlying cause of shortness of breath is treatable. To determine the cause of this condition and how best to treat it, your doctor will likely perform a physical exam and request some tests, such as a chest X-ray, blood tests or heart tests.

If the cause can’t be determined or if your doctor can’t treat the underlying cause, he or she will try to relieve the discomfort of shortness of breath. Having oxygen or cool air blown across your face may be helpful. Opioid medications, such as morphine, also provide relief by blunting the sensation of being short of breath. An inhaler or nebulizer that delivers medication to your lungs may provide relief.

Appetite changes and weight loss

With advanced cancer, you may find your appetite diminishing and your weight dropping. Your loved ones may be disturbed by your inability to eat, perhaps because we tend to equate a hearty appetite with good health. There’s no evidence, however, that a person with advanced cancer will live any longer if he or she eats more. Pressuring someone to eat can cause stress and nausea, which is an unnecessary burden if he or she is already experiencing the effects of advanced cancer.

If you’re bothered by your loss of appetite, try these methods to possibly stimulate appetite:

In addition to trying these self-help tips, you might want to talk with your doctor about a prescription appetite stimulant. Perhaps the most widely prescribed and best studied is megestrol acetate (Megace). This drug also has an anti-nausea effect.

Nausea and vomiting

Loss of appetite and weight may be related to nausea and vomiting. Nausea and vomiting can result from many causes, such as spread of the cancer to the liver, interference with normal digestive functioning due to cancer spread to the intestines, constipation, and use of pain medications. Eating only those foods that appeal to you and eating frequent, smaller meals instead of three large ones may help. Anti-nausea medications may help to some degree. Those commonly prescribed to stimulate appetite (megestrol acetate and corticosteroids) also may help to decrease nausea and vomiting. Some people find patches for motion sickness that contain the medication scopolamine to be helpful.

If you experienced nausea and vomiting while receiving chemotherapy, you may have gotten relief from drugs designed to treat chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. These same drugs may also help when nausea and vomiting are caused by advanced cancer rather than chemotherapy.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Palliative care is a relatively new specialty that aims to reduce pain and improve quality of life for people who have advanced illnesses, as well as provide support for their families. Palliative care takes into account the emotional, physical and spiritual needs and goals of the person who’s being treated and his or her family. Palliative care doesn’t replace primary medical treatment. Instead, it’s provided in conjunction with other medical treatment.

Palliative care grew out of the hospice movement, but it differs from hospice in that it’s available at any time during a serious or life-threatening illness, while hospice care is available only during the final months of life — when curative or life-prolonging treatments have been stopped. You don’t have to be in hospice to receive palliative care.

Who can benefit from palliative care?

Anyone who has a serious or life-threatening illness can benefit from palliative care, either to treat signs and symptoms of the disease or to ease the side effects of treatment. In addition, palliative care can help if you or a loved one needs help understanding more about an illness or coordinating medical care.

Palliative care is available whether you or your loved one is being treated as an outpatient, in a hospital or nursing home, or through hospice. Often, palliative care specialists work as part of a multidisciplinary team to coordinate care. The team may be comprised of various specialists, including doctors, nurses, social workers, psychologists, counselors, chaplains, registered dietitians and pharmacists.

A palliative care specialist works with your primary care doctor and other members of your medical team to create a care plan that eases symptoms, relieves pain, addresses spiritual and psychological concerns, and helps maintain dignity and comfort. Together, these steps can lead to an improved quality of life.

A palliative care specialist can also help you or your loved one communicate with doctors and family members and create a smooth transition between the hospital and home care. If necessary, a palliative care specialist can help coordinate financial and legal assistance.

Research shows palliative care has a number of benefits including less time in the hospital, more time at home among family and friends, better control of symptoms, increased satisfaction with medical care and a reduction in the cost of care. People who seek palliative care also have a higher likelihood of dying at a place of their own choosing, such as at home instead of in a hospital.

If you’re interested in obtaining palliative care for yourself or for a loved one, ask for a referral to a palliative care specialist.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Hospice is the term used to describe special programs in which a group of individuals — the hospice team — works together to provide optimal supportive care for terminally ill individuals and their families. The hospice team usually includes doctors, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, therapists, chaplains, volunteers and others. Hospice programs strive to enhance quality of life, while neither delaying nor hastening the dying process.

For some people, hospice care means the end of hope. It’s true that hospice care can begin only after hope of a cure is gone, but initiating hospice doesn’t mean that all hope is lost. The goal of hospice is to help you live well during the time you have remaining and to help you die with peace and dignity.

Most hospice care is provided at home, but it may be provided in nursing homes and other residential settings. A few hospice programs have their own hospital or clinic facilities. In a home setting, although nurses and other members of the hospice team make visits as needed, the program is designed so that the person who’s dying receives much of his or her care from loved ones, who can get advice and support from the hospice team 24 hours a day, seven days a week, whenever they need it.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

In the United States, modern-day hospice care began in Connecticut in 1974. The Connecticut Hospice in New Haven was modeled after a concept developed by Dame Cicely Saunders, a social worker who in 1967 opened the renowned St. Christopher’s Hospice in Sydenham, England. Dame Cicely was so committed to providing high-quality, compassionate care for people near the end of their lives that she became a doctor to realize her goal. Her model of palliative care has since been replicated many times over in England, the United States and throughout the world.

Although hospice services initially were designed primarily for people with cancer, today they’re available to people with other terminal illnesses, too.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Services offered

Hospice programs are designed to give access to around-the-clock support to terminally ill people and their families. The hospice team works with you and your loved ones, adjusting the services provided according to your needs and those of your family. Physical, social, spiritual and emotional needs are addressed throughout the last stages of illness and during the period of bereavement that follows a death.

Hospice programs provide comprehensive services, including management of symptoms, emotional support for you and your family, and spiritual care. Emotional (psychosocial) support is intended to help you and your family members deal with issues or problems you or they may be facing, such as depression, anxiety and fear. The intent of spiritual care is to help you maintain hope and address any questions you may have, perhaps about the meaning of your life.

Depending on the individual, hospice services may include:

The hospice staff generally provides bereavement services to family members for up to a year after a loved one’s death.

Eligibility

You’re eligible for hospice services when you stop treatment aimed at curing or controlling your cancer and your doctor indicates that — if your disease follows the expected course — you’re expected to live six months or less, a criterion established by Medicare. As long as you continue to meet the criteria, you may continue to qualify for hospice care. This may be longer than six months for some individuals.

Although hospice care is widely acknowledged as being very worthwhile for people nearing the end of their lives, only 20 to 50 percent of people with cancer who are eligible for hospice services receive them. And for individuals who do enroll in hospice, the average time they receive hospice services is just a few days to a few weeks, too little time for them to receive the full benefit of the range of services hospice offers. This is partly because of some people’s reluctance to call hospice or because of their family member’s inability to accept that a loved one is dying.

In addition, some doctors are reluctant to refer people to hospice, not because they don’t see it as worthwhile but because they’re hesitant to give up on anti-cancer treatment, or they don’t want to tell individuals that they’re dying.

Do-not-resuscitate status

The best time to make decisions about emergency care is before you need it. An example is when to decide on do-not-resuscitate (DNR) status. If you stop breathing or if your heart stops beating, do you want doctors to use extreme measures to try to bring you back? Extreme measures include performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), shocking your chest to try to restart your heart or putting you on a machine that breathes for you (ventilator).

If you decide that you don’t want to be resuscitated, it’s best to convey that information to your health care team as soon as you make that decision. Requesting DNR status doesn’t mean that you or your doctor will give up on your care, or that you cannot receive care for unrelated or potentially reversible conditions. DNR means that you don’t want extreme or heroic measures taken to extend your life, if you were to die.

Attempting resuscitation in people with advanced cancer usually isn’t effective at helping them get stronger, live longer or get out of the hospital. Doing so may prolong the dying process and it may cause more pain and suffering. Even if a person is “successfully” resuscitated in the short term and placed on a breathing machine, he or she may not be able to breathe independently again. And the family may then be faced with the decision of when to take the individual off the ventilator.

Doctors are mandated to discuss DNR status with all people who enter a hospital. Otherwise, the subject might not come up unless you were to initiate it. Some people hesitate to sign a DNR order because they’re holding onto the hope that coming back to life will give them another chance at beating their disease. Unfortunately, this is very unlikely with advanced, incurable cancer. They also believe that if a DNR order is in place, they may not receive routine care or they’ll be abandoned, both of which are not true.

If you have these concerns, talk with your doctor and your family members about DNR status and what it does and does not mean regarding your care.

![]()

As a person faces the prospect of death, he or she is likely to experience a host of feelings, including fear, concern about those left behind and possibly anger. Some people don’t understand the concept of a good death. The following true story may help.

Gayle’s Story

Gayle was diagnosed with a large breast cancer that had spread beyond the breast at the time of her diagnosis. For the next two and a half years, she was treated with surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy and hormone therapy. At times, as part of her treatment, she needed to have catheters placed in the tubes that lead from the kidneys to the bladder (ureters).

Although the chemotherapy was hard on her, she continued to live her life, enjoying time with family and friends until her final moments. Throughout her treatment, she had open discussions with her oncologist regarding the pros and cons of various treatment approaches. She and her family were actively involved in her treatment decisions. Eventually, she reached the point where she was no longer responding to a number of anti-cancer treatments, such as hormone therapy and chemotherapy. She chose to spend her final days at home with her family, receiving hospice care.

Three weeks before her death, on the day she, her family and her doctor concluded that treatments aimed at slowing the cancer’s growth were no longer working, Gayle attended a high school football game with her family. One week before her death, one of her sons and his wife invited many close friends and family members to their home for a celebration of life, to allow Gayle and her family and friends to reflect on the many good times they had shared. It was also an opportunity for words of thanks and heartfelt goodbyes.

Several days before her death, with her youngest son’s encouragement, Gayle wrote to each of her three sons. Her inspiring words provide an excellent example of making sure that loved ones know what they mean to you at the end of your life. Her children, reading her words at her funeral, called it “a special gift from an incredibly special woman.” This is some of what she wrote:

To Our Firstborn — Jeff

We’ve always loved you best because you were our first miracle — the fulfillment of young love, the promise of our infinity. You sustained us through the hamburger years, the first home — furnished in early poverty — the many monthly payments, trying to make ends meet.

You were new, had unused grandparents and more clothes than a Barbie doll. You were the “original model” for unsure parents trying to work the bugs out. You got the strained lamb, open pins, tiptoe treatment and three-hour naps. We have always expected a great deal from you, and you have not disappointed us. God has blessed us because you’ve been a fine example to your younger brothers — and we love you for it.

You were the beginning.

To Our Middle Child — Jim

We’ve always loved you best because you drew the dumb spot in the family, and it made you stronger. You cried less, had more patience, wore faded clothes and never did anything “first.” With you, we realized you could kiss a dog or miss a nap and not get sick. You crossed the street before you went to kindergarten, and we didn’t get an ulcer about your using a hammer.

You were the child of our busy, ambitious years. Without you, we never could have survived job changes and the house we couldn’t afford. You’ve always endured the pressures of an older brother’s achievements and a younger brother’s gregariousness. And we’ve loved you for it.

You were the continuance.

To Our Baby — John

We’ve always loved you best because endings are generally sad, and you are such a joy. You readily accepted the milk-stained bibs and the secondhand toys, skates and bikes.

You are the one we hold on to so tightly. For, you see, you are the link with the past that gives reason to tomorrow. You quicken our steps, square our shoulders, restore our vision and give us humor that security and maturity can’t give us. And we’ve loved you for it.

You are lucky to have two older brothers who have taught you so much and set fine examples for you. When you are older, even when your children tower over you, you will still be “the baby.”

You were the culmination.

In the last week of her life, Gayle told her husband that she needed to plan her funeral. Using the excuse that he was older than she, he said they needed to plan his funeral first. So that day, they planned both of their funerals, first his, then hers.

On the day she died, she called her children and grandchildren to be with her that afternoon. They all said their goodbyes and shared some last moments with her. When her oncologist came to visit her, he found her resting comfortably, her home filled with three generations of her extended family.

Shortly after the oncologist’s visit, Gayle’s parish priest arrived. With Gayle’s family present, the priest asked if she felt safe. He told her she was about to go to a better place and asked if she was ready to die. She replied to both questions with a smile and a nod of affirmation. She died peacefully six hours later.

![]()