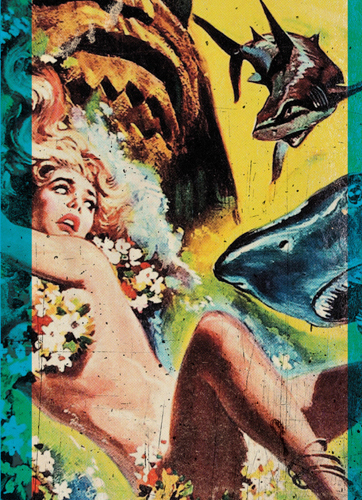

Detail from the U.S. poster for House of Usher (1960), directed by Roger Corman.

ROGER WILLIAM CORMAN was born on April 5, 1926, in Detroit. The first of two sons born to William and Anne Corman, Roger spent his early years devouring Edgar Allan Poe’s tales of terror, building balsa-wood model airplanes in the bedroom he shared with his younger brother, Gene, and sneaking off to the movies to imagine himself as Clark Gable’s Fletcher Christian in Mutiny on the Bounty. During those early years, at the height of the Great Depression, Corman’s father found steady work as an engineer, designing roads, bridges, and dams for McCray Steel. Even though the Cormans were solidly middle class, with a home on a shady, tree-lined street in the city’s Six Mile Road neighborhood, they weren’t immune to the economic hardships that were hitting most Americans. No one was. William never lost his job, but his salary was reduced in order to cut costs at the company. Frugality became a virtue in the Corman household—and was a lesson that young Roger would never forget.

In 1940, when Roger was fourteen, his family moved to Beverly Hills, after a doctor told his father that he had a serious and possibly fatal heart condition. California was like a sun-kissed alien planet to Roger. When he enrolled at Beverly Hills High School, it was the first time he remembers socializing with the sons and daughters of wealth and privilege, many of whom were the children of well-known and well-off movie studio executives. After graduation, Roger was accepted to Stanford University in Palo Alto—three hundred and fifty miles to the north of Los Angeles. There he studied industrial engineering in large part to make his father proud. The subject appealed to Corman’s methodical, problem-solving mind. But after he began reviewing movies for the Stanford Daily, math and science couldn’t compete with Marlene Dietrich and Spencer Tracy.

When Corman graduated from Stanford in 1947, the war was already over and even though he had enrolled in a Navy officer training program, his service was complete. Now he saw the career path laid out before him and shuddered. Engineering was a lucrative and respectable profession, but it wasn’t his passion. His passion was back in the pages of Poe and the hushed darkness of the matinee. Through a family connection, Corman landed a job as a messenger in the 20th Century Fox mail room, earning $32.50 a week. He had finally stepped inside the Hollywood Dream Factory, walking on the same hallowed ground as Tyrone Power, Betty Grable, and studio head Darryl F. Zanuck. Corman knew that he would never pick up a slide rule again. Soon, he was promoted to the position of story analyst; he would synopsize lousy novels and even lousier spec scripts and give his notes, suggesting which properties deserved to go before the camera. One of the few stories that got his attention was a Western called The Big Gun, which was later made into 1950’s The Gunfighter, starring Gregory Peck as a reformed gunslinger who can’t outrun his notorious past. Corman had found the story and had given notes to make it better. And even though his suggestions were used in the finished film, Corman didn’t receive the credit he thought he was due. Instead, his boss got a juicy bonus. If this was how the studio game was played, he wanted out.

Corman left Fox and enrolled at Oxford on the GI Bill, studying English literature. But after six months, he gave up the ivy-covered campus and headed for Paris, where he lived off of his government stipend while hitting jazz clubs with his fellow expats. When his funds ran out, Corman returned to California in 1952 and found steady work at a string of literary agencies. On the side, he began writing a screenplay of his own about a Korean War vet who’s wrongly accused of killing a woman. He called it The House in the Sea, and it sold for $4,500 to Allied Artists, who rewrote the thriller and renamed it Highway Dragnet, to cash in on Jack Webb’s hit TV show. It was hardly an auspicious debut, but it was a debut nonetheless. Corman received his first professional credits, as cowriter and associate producer on the film.

Distraught at how his script had been butchered, Corman started his own company, Palo Alto Productions, with his brother Gene. They didn’t have enough money for a secretary, but they had an address. The shoestring operation was run out of a claustrophobic shared office above the Cock ’n Bull pub on the neon-lit Sunset Strip. Palo Alto’s inaugural film was 1954’s Monster from the Ocean Floor, a ridiculous cheapie about a preposterous one-eyed sea creature. It was shot in six days for $12,000, and it was a success. Just like that, Corman was a successful Hollywood producer. For his follow-up, he chose The Fast and the Furious—a high-speed chase film about an escaped con who kidnaps a young woman and hightails it across the Mexican border. The film got the attention of Sam Arkoff and Jim Nicholson, who were about to start a new company of their own: American International Pictures (AIP). Arkoff was a bigger-than-life, cigar-chomping cartoon of a producer, and he struck a deal with Corman, providing financing for a slate of future movies. At the time, the big studios were still reeling from the one-two punch of television’s encroachment on ticket buyers and the government’s recent anti-trust crackdown, which forced the majors to relinquish their vise-like grip on the theater chains they owned. It was the perfect time to get into business with a ballsy independent like AIP.

AIP quickly found itself in hot demand to fill the exploding number of drive-in theaters with B pictures to unspool before the studios’ ritzier A films. It wouldn’t take long for Arkoff and Nicholson’s company to become the biggest—and brashest—independent distributors in Hollywood. And Corman, fueled by ambition and a Herculean work ethic, became AIP’s star director, cranking out as many as twelve pictures a year. He made them fast and cheap, with an eye on the bottom line and an ear for lurid titles that were like catnip for teenage audiences—It Conquered the World, Attack of the Crab Monsters, and Teenage Caveman. Corman had always had a sweet tooth for science fiction, but the businessman in him knew that these were also the sorts of movies that would click with the growing teenage audience. Corman wasn’t much of a stylist at first. He was working too quickly for that to even be a consideration. But one way he thought he could get better was to start sitting in on acting classes, where he might cross paths with young actors and actresses who couldn’t get their feet in the doors of the big studios—anonymous wannabes with vanilla names like Jack Nicholson, for example.

By the end of the fifties, the bleary-eyed Corman had somehow managed to direct a staggering twenty-four movies. He was making money hand over fist for AIP, but he wasn’t getting rich himself. So he decided to go into the distribution business, putting Palo Alto aside and creating a company called Filmgroup. Roger was working fast and furious now. And on a bet, he proved just how speedily he could work, shooting Filmgroup’s first feature—a subversive, bruise-black comedy called The Little Shop of Horrors—in just two and a half days on a budget of $28,000. It was a remarkable feat. More remarkable still was just how assured Corman had become behind the camera by the time the curtain fell on the decade. He was starting to develop a personal style. His camera set-ups were getting more ambitious. The scripts were funnier. Young, hip audiences were no longer laughing at him, but with him. Soon the critics would discover that Corman was more than just a quickie conveyer-belt filmmaker—especially after he reached back into his past and conjured the macabre stories that haunted his childhood in a series of indelible and incredible Edgar Allan Poe films.

Publicity shot of Corman from the early 1960s. The son of a successful engineer, Corman was a gifted student who attended Stanford and Oxford. But beneath his buttoned-down exterior raged the mind of a maverick who would turn lurid tales of monsters, murder, and teenage rebellion into drive-in gold.

ROGER CORMAN (director, producer): “I was always interested in the movies. I went to Stanford as an engineering major because my father was an engineer and I thought I would follow in his footsteps. But then I started writing for the Stanford Daily and found out that the paper’s film critics got free passes to all of the movie theaters in Palo Alto. That’s when I started looking at pictures in a different way. Rather than just entertainment, I began to analyze them and became more and more fascinated.”

GENE CORMAN (producer): “I remember one afternoon at my fraternity house at Stanford, I read an article in the New Yorker magazine about a motion picture agent who played tennis all day and centered his career around the Beverly Hills Tennis Club. I thought, Holy shit, what a life! He had every girl in town, went to every party. I had no interest in a real career, so when I graduated in 1948, I decided I’d like to be an agent like that guy. Charlie Feldman was one of the most important and powerful agents at the time, and his partner, Ralph Blum, was opening a new office. I went in and the receptionist said, ‘We might actually have something for you.’ I think I got $25 a week. In the meantime, Roger had started life as an engineer, and he was not happy about that. Our father knew that Roger was very frustrated and didn’t want to go into engineering. And like every father, you want your children to be successful and happy.”

ROGER CORMAN: “My first job in Hollywood was in the 20th Century Fox mail room. I delivered interoffice memos on a bicycle. I was the failure of the Stanford engineering class because I got the worst job of anybody. I was making $32.50 a week. At that time, production on the studio lot was six days a week. I volunteered to work for nothing on Saturday if I could work on a film set. That’s when I began to understand my real purpose, which was to learn a little bit about how films were made and also to let them know I was a hard worker. The head of personnel said there was an opening in the story department for an analyst. Basically, you would read scripts and stories that were submitted to the studio for possible purchase. My salary nearly doubled! One day, the story editor called me in and said, ‘Roger, you’ve turned down every single script you’ve been sent. Don’t you like anything?’ I said, ‘I’m the youngest guy here, so you give me all the worst stuff. Give me something that’s worth commenting on!’ And shortly afterward they sent me a Western script called The Big Gun, which I thought was really good. I gave my notes, and it became The Gunfighter with Gregory Peck. The story editor got the praise for my notes. That was frustrating. So with some time I had left on the GI Bill after my time in the Naval Training Program, I went to Oxford to study English literature. I was just there for two quarters, then I left for Paris and had all of my mail forwarded to the American Express office there, including my subsistence checks on the GI Bill. I figured if I spent a couple of months in Paris before coming home, who’s going to check that these checks were cashed in Paris? When I came home, I started working at the Richard Hyland Agency and wrote a script called The House in the Sea. It was the first script I’d ever written. And when I sold it, I offered to go along for nothing if I could get a credit as an associate producer. Even then, I understood that credits were important. They changed the title to Highway Dragnet because Dragnet was a popular TV series at the time. I took the $4,500 I made from that sale and borrowed money from some of my more successful college classmates and made Monster from the Ocean Floor—a monster film about a mutation created from atomic explosions.”

U.S. poster for The Gunfighter (1950), directed by Henry King. Corman was working as a young story analyst at 20th Century Fox when he read and recommended a Western script called The Big Gun, which later became The Gunfighter, starring Gregory Peck. Someone else got the credit for his keen eye. The snub stung and helped push Corman to go into business for himself.

JONATHAN HAZE (actor in more than a dozen Corman films, including The Little Shop of Horrors): “I was working in a gasoline station on Santa Monica Boulevard called Tide Oil, and a little funny guy kept coming in named Wyott Ordung. He kept telling me he was a writer and was going to direct a movie and he would put me in the movie. One night he came in and said, ‘Listen, I want you to go see Roger Corman. He’s doing this movie called Monster from the Ocean Floor, and there are some parts in it you might be able to get.’ So I went to see Roger, and he hired me to play a Mexican deep-sea diver. It was low-budget but a lot of fun. I was happy to be working. I got fired from the gas station because I grew a mustache for Monster from the Ocean Floor, and the owner of the gas station came in one night and saw the mustache and said, ‘What’s that thing on your face?’ I told him I was growing it for a movie. And he said, ‘Either the mustache goes or you go.’ So I went.”

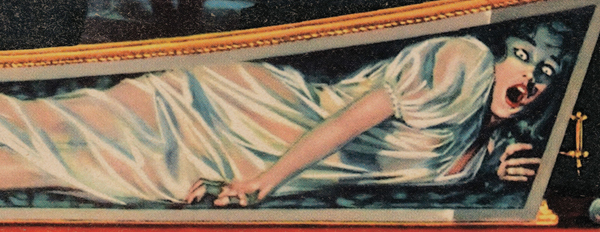

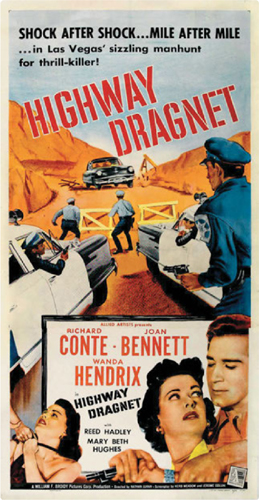

U.S. poster for Highway Dragnet (1954), directed by Nathan Juran. Hugely ambitious and convinced that he could do better than the scripts that were landing on his desk at the Richard Hyland Agency, Corman penned a thriller called The House in the Sea. He was paid $4,500, and it was retitled Highway Dragnet to cash in on the popular Jack Webb TV show.

Lobby card for Monster from the Ocean Floor (1954), directed by Wyott Ordung. Corman hit up a few of his former Stanford classmates to help bankroll this low-budget quickie (it was shot in Malibu in six days) that toyed with Atomic Age anxieties. Their investments paid off: The film grossed five times its budget. Still, the most memorable thing about the film remains its title.

U.S. poster for The Fast and the Furious (1955), directed by John Ireland and Edward Sampson. The high-speed hostage thriller (produced by Corman) got the attention of American International Pictures—the fledgling independent exploitation studio that would become Corman’s on-and-off backer for more than a decade. Proving that even early on he knew how to find actors on the cheap, Corman cast himself as a state trooper. Four and a half decades later, the title would be recycled for a big-budget franchise starring Vin Diesel.

GENE CORMAN: “Roger drove the truck and did almost everything on Monster from the Ocean Floor. As an agent, I represented the film, and I sold it to Bob Lippert, who had an independent distribution company at the time. I think I sold it for something like $150,000, and the picture cost maybe $30,000. Roger did very well, and that began his run as an independent producer.”

ROGER CORMAN: “Next, I made The Fast and the Furious—a little film starring John Ireland as a wrongly accused man who breaks out of jail and heads to Mexico with a female hostage in a sports car. I had offers from a number of smaller studios because it was a good little picture. But I could see the trap for an independent low-budget producer like myself. If you made a film and you didn’t have much money, you had to wait for the film to be released and earn its money back before you could make the next film. I had offers from Republic and Universal to distribute my films, but Jim Nicholson and Sam Arkoff were starting a new company called American International Pictures, and they were looking for pictures to pick up. I explained my situation, and I said I had a plan that might fit their company: I wanted an advance equal to my negative costs on The Fast and the Furious, and I would commit to make two more films, and I’d pay them back as they opened. From the beginning, we were all in it together. The next movie I made was a Western called Five Guns West. That was my first time directing. I had seen what the directors were doing on the first two films I produced, and I thought, I could do that!”

Frame grabs from Five Guns West (1955), directed by Roger Corman. Corman’s debut behind the camera was a simple but effective story about a quintet of ruthless Civil War outlaws who are pardoned and forced to join the Confederate Army. Jonathan Haze shoots first and presumably asks questions later.

ROBERT TOWNE (writer; post-Corman screenplay credits: The Last Detail, Chinatown, Shampoo, and Mission: Impossible): “Jim Nicholson was a slender man, and Sam Arkoff, who was sort of the archetypical producer, was kind of heavyset. Both men were given to wearing suits. And Arkoff was always smoking a horrible cigar. It wasn’t even a good cigar. And he was given to saying things like ‘artsy-fartsy.’ That’s how he would dismiss movies that had any intelligence.”

ROGER CORMAN: “AIP realized they were in the B-movie business from the beginning. Over time it became clear that our audience was the youth audience, and we began tailoring our films to that. What was normally done was we took something out of the headlines and grafted it onto a science fiction/monster movie premise. So right from the beginning we were either ahead of the curve or right on the curve of what teenagers were interested in. I probably made forty pictures with AIP. They didn’t play it as safe as the studios. They were willing to gamble and experiment. That’s why they rose so quickly. And Sam Arkoff was the smartest negotiator that I ever met in the motion picture industry. In business, of course, you always try to get the edge. And I remember on one picture we were working out the budget, and we were $10,000 apart on my fee. I said, ‘Sam, I’ll flip you for the last $10,000.’ We were all young at the time, and the dollar was worth maybe a fifth of what it is now. So for a couple of young guys who didn’t have a great deal of money, this was an audacious proposal. And Sam immediately said OK. We flipped, and I won the $10,000. On every negotiation from there on in, Sam somehow negotiated to the point where we were always $10,000 apart, and we’d always flip for it. And after my first win, he won every single time. I told him after a while that I wanted to examine the quarter.”

Frame grabs from The Fast and the Furious (1955). The title card promises fiery crashes; the producer card holds a different kind of promise—Corman’s first producer credit. In time, he would rack up more than four hundred of them.

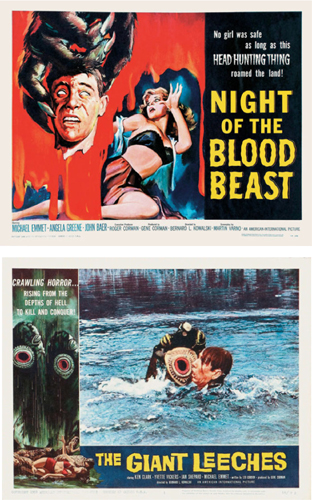

GENE CORMAN: “Roger started to be very successful. We’re brothers, so I said, ‘Roger, do you think there’s any chance I could join your organization?’ Blood is thicker than anything else, so he said, ‘Come aboard!’ And I never looked back. Roger, even at the beginning, was smarter than ninety percent of the people in this town. At that point in time, the drive-in was everything. And to play a drive-in, you had to have something they could exploit. We couldn’t get actors of substance, and you had to have something to hang your hat on, so we felt exploitation and horror was what the marketplace wanted. Movies with titles like Night of the Blood Beast and Attack of the Giant Leeches. You could make them cheaply, and you didn’t need a big name—you just had to have a great poster. That’s how you sold everything!”

Promotional shot of American International Pictures’ James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff showing off some of their exploitation wares. The duo were among the first studio heads to tap into an underserved teen drive-in market with daring double features promoted with huckster flair. Soon they would become the Barnum & Bailey of B movies.

ALBERT RUDDY (producer; post-Corman credits include The Godfather, The Longest Yard, The Cannonball Run): “I worked on one of Roger’s first films, 1955’s The Beast with a Million Eyes. I did everything from production design to special effects. I was going to college at USC, and this girl I was going out with got a job on a Roger Corman movie. They were shooting it in the desert past Palm Springs. I loathed the idea of this girl going away all summer without me, so I called the director and asked if I could get on the movie. I think it was about these surreal monsters who come to Earth because their bodies have decayed in outer space, and they’ve come to get human bodies. They have to work their way up the food chain, so when they first come here, they start attacking the chickens. Then they start to go after goats, then the cows, and then the people. There’s a scene where this woman is feeding the chickens corn, and I’m behind the camera, with a cage full of chickens, and I had to start throwing the goddamn chickens right in her face as she’s screaming! It was a nice scene, took about ten minutes to do. The director asked me to design a monster for $50. I got one of these extended aluminum pieces with a mop at the end, then I got a red rubber syringe that you squeeze in your ear, and painted it all a slimy green. That’s what I had for this goddamn thing! And then I painted on an eyeball with veins. Roger was smart, because he set up a machine. Look, you can’t sell one or two movies on their own in this town. But if you say, ‘Guys, I’m going to deliver twenty movies for you over a period of a year,’ they love that! Roger was smart enough to understand that he was going to deliver in bulk. It was revolutionary, what he did.”

An early incarnation of the AIP logo that appeared before films, boasting titillating tales of “High School Hellcats, Reform School Girls, and Hot Rod Gangs.”

U.S. poster for Night of the Blood Beast (1958) and lobby card for Attack of the Giant Leeches (1959), both films directed by Bernard L. Kowalski and produced by Roger Corman.

Still from The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955), directed by David Kramarsky. Corman executive-produced this cheapie about an absurd-looking monster with an abundance of eyeballs (although a million is pushing it). Albert Ruddy, who would later produce The Godfather, was a jack-of-all-trades on the film and says he was given $50 to design the beast. Not bad for fifty bucks.

MONTE HELLMAN (director; post-Corman credits include Two-Lane Blacktop): “I was working as an apprentice editor at ABC Studios, cleaning out film vaults and doing all kinds of things that were terrible for my allergies. I would go up to Griffith Park for lunch to get some fresh air and eat my sandwich out of a paper bag. And one day, I saw Roger up there shooting a scene for one of his movies. He became my instant hero because he was doing what I was dreaming of doing.”

DICK MILLER (actor in more than fifty Corman films; also appeared in Gremlins and The Terminator): “The first movie I made for Roger was 1955’s Apache Woman. I’d come out to California as a writer—I had no intention of being an actor at all. A buddy of mine, Jonathan Haze, had just done an undersea monster movie for Roger, and he had to drop something off at the office. So we went out to see Roger. His tiny little office was over the Cock ’n Bull Restaurant on the Sunset Strip. He wasn’t really sharing an office, he was sharing a desk. He was poor. And in the course of conversation, he says, ‘Where are you from?’ I said New York City. He said, ‘What do you do?’ I said, ‘I’m a writer.’ And Roger said, ‘Well, I don’t need writers. I’ve got plenty of writers. I need actors.’ I said, ‘Fine, I’m an actor.’ He said, ‘Do you want to work in my next movie?’ I said, ‘Yeah, sure.’ They put some dark makeup on me and I played an Indian who got shot in the movie. And after we finished shooting the Indian part, he says, ‘Nice work, blah blah blah. How’d you like to be a cowboy for me?’ I said, ‘Oh, you’re shooting another Western?’ He says, ‘No, the same Western.’ That sort of told me what kind of picture we were dealing with. I said, ‘Oh, God … OK.’ So I played a cowboy and an Indian in the same movie—I think I may have even shot myself! We’ve done forty-nine pictures together since then. For sixty years, Roger and I have basically had a no-contract arrangement. He’d say, ‘You want to work?’ ‘Well, yeah, I want to work.’ That’s it. He’s a remarkable guy. If I never ran into him all those years ago, I’d be sixty years older, telling people I’m a writer. I owe my career to him.”

U.S. poster for The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955), starring Paul Birch, Lorna Thayer, Dona Cole … and the Beast. In Terror-Scope, no less!

U.S. poster for Apache Woman (1955), directed by Roger Corman. Does that mystery man with the gun in the foreground look familiar? If so, that’s because it’s Lloyd Bridges, a few years before his vault to stardom with the hit TV show Sea Hunt. Dick Miller, who would go on to appear in more than fifty Corman films, made his debut in this Western playing both a cowboy and an Indian.

U.S. poster for The Cry Baby Killer (1958), directed by Jus Addiss. Corman executive-produced this tense hostage drama, starring a then-unknown twenty-one-year-old named Jack Nicholson in his big-screen debut. Corman met Nicholson in an acting class and saw something in him—even if he didn’t quite know what at the time. Nicholson didn’t possess traditional leading man looks, but soon any idea of what a “movie star” looked like would be tossed aside.

ROGER CORMAN: “I met Jack Nicholson in Jeff Corey’s acting class. When I started directing, I understood the technical aspects of the job pretty quickly—maybe because of my background in engineering. But I didn’t feel like I knew enough about acting. So I enrolled in a Method acting class and met Jack and started using him in films like 1958’s The Cry Baby Killer. I specifically was looking for the best young talent I could find in every category—writers, producers, actors, cameramen, editors. I did anticipate that they would have good careers, but I had no idea that some of them would have careers as spectacular as they were. One of the reasons I’ve stayed on good terms with all of them is that I never did what I was advised to do, which is sign someone to a two-picture deal so that I could have them tied up on a second picture. I felt that was unfair. I felt that I’m paying them a small amount of money, but they’re getting their first chance—so it’s a fair deal on both sides. I think that’s one of the reasons that everyone looks back fondly. We were all young and we were friends and we were having a good time. Now, in the same acting class where I met Jack, I also met Robert Towne. He and Jack and I all used to hang out together. Like Jack, he eventually moved up the ladder and won an Academy Award for Chinatown.”

Production still from The Cry Baby Killer (1958). Nicholson holds a hostage at gunpoint. It’s unclear who looks more frightened. Nicholson has a smoldering intensity in the film, though didn’t seem sure how to harness it yet. To this day, he credits Corman with discovering him, saying, “Roger’s the only guy who hired me for ten years.”

JACK NICHOLSON (actor, writer; post-Corman credits include Easy Rider, Chinatown, and The Shining): “He came into the class—that little smile when everyone’s serious as a heart attack. When I was first working for him, he told me he had twelve companies, the contracts of which were all in his back pocket. He was a oneman band. … I hadn’t really worked at all before. When I got a lead in a movie, I thought, This is it! I’m here! I’m gonna be big! Then I didn’t even get an interview for the next year. … Cry Baby Killer was just humiliating, but good for me. Hey, Roger’s the only guy who hired me for ten years.”

DICK MILLER: “Jack, he came up the hard way. He wasn’t a star overnight. But the fact that Roger saw something in him. … I mean, anyone would have. But that’s just the nature of the business. You have to take parts. Not the parts you want, but the parts you get.”

F. X. FEENEY (writer, 1990’s Frankenstein Unbound; film critic): “When I think about Roger’s legacy, I think of that line from Shakespeare’s Macbeth: Thou shalt get kings, though thou be none. He helped filmmakers and actors find themselves. He gave starts to so many people. His talent was finding talent and putting talent to work.”

ROBERT TOWNE: “I met Roger in Jeff Corey’s acting class in 1957. Jack Nicholson was there, Richard Chamberlain, Sally Kellerman, the director Irvin Kershner, who directed Stakeout on Dope Street for Roger. It was a colorful class with a lot of characters. Roger studied engineering at Stanford, and he took kind of a systematic approach to things. He was there to learn about acting to help his directing. Pretty smart. I don’t think Jeff Corey was as impressed with Jack as I was. I went up to Jack when he was eighteen and said, ‘Kid, you’re going to be a movie star, and I’m going to write for you.’ It took a while, but it eventually happened on The Last Detail and Chinatown. Outside of class, Jack and I palled around. Eventually, we ended up rooming together at 563 ½ Westford. That must have been 1957 or 1958. It was a tough time. We were struggling. And I remember on Academy Awards night, we’d sit there and bitch about trying to get a job. We were just filled with stories of hilarious disappointment. There were a few women who would come around, but most of the women who were our age, they preferred to date guys who had cars or who could take them out somewhere. The first thing I wrote for Roger was a script called Fraternity Hell Week. It never got made. Monte Hellman was going to direct it, and he and Roger had this idea to cut the script into little individual scenes. So they cut the script into these tiny eight-page sequences. And then they promptly lost them. None of us had an extra copy of it. I didn’t think much of the script anyway, so I didn’t mind. I think that other people did much better work for Roger than I did. Although I do like Tomb of Ligeia. I think that’s one of Martin Scorsese’s favorites.”

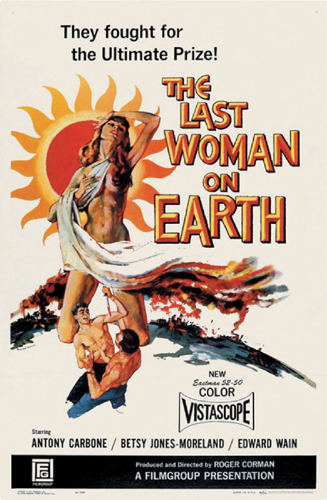

U.S. poster for The Last Woman on Earth (1960), directed by Roger Corman. Always looking for ways to save a buck, Corman would often try to squeeze two movies out of a single location. This apocalyptic love story was piggybacked onto the production of 1961’s Creature from the Haunted Sea in Puerto Rico. Robert Towne, who would later win an Oscar for his script for 1974’s Chinatown (starring Jack Nicholson), did double duty as both Last Woman’s screenwriter and one of its stars (credited under the name “Edward Wain”).

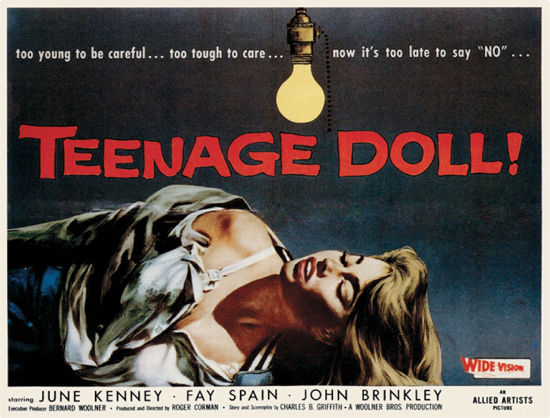

MARTIN SCORSESE (director; post-Corman credits include Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and Goodfellas): “Me and my friends from Mott Street, we spent a lot of time at the movies as teenagers. We saw everything. Whether it was Last Woman on Earth or Creature from the Haunted Sea—I mean, come on, with a title like that, how can you not want to go? We saw Machine-Gun Kelly, Teenage Doll, Rock All Night, and we began to notice that there was a different style with his films. They were different from other B or C movies at the time. They may not have all been great films, but we knew that there was something happening behind the camera. We knew there was something special—a kind of vision behind them. They got our attention. Watching something like Attack of the Crab Monsters, which is a hilarious title but an even funnier film, you realized the whole genre was being sent up and you were in on the joke. I’ll never forget going to see one film playing on a double bill—the bottom half of a double bill—She Gods of Shark Reef. We thought that was hilarious. We weren’t laughing at it. We were laughing with it. The whole idea, the way it was made, you never really see the She Gods of Shark Reef, you know? But we accepted it. Of course we’re not going to see the She Gods! Of course not! I think it’s in Not of This Earth where they had the alien talking about having some kind of transformation that had to take place with the humans, their blood supply, or something like that. And they ask him why, and he goes, ‘No, it would be too difficult for you to understand.’ And then they move on! We were like ‘OK, we accept that. Let’s go on with the rest of the movie.’ Corman’s films didn’t look as if they were coming out of the studios. They had these preposterous plots and wild acting. And once we were let in on the joke, we embraced it. Anytime his name came up on the poster outside of the theater, we said, ‘All right, we’re going with this guy.’ I was seventeen or eighteen when I saw House of Usher. That was a revelation. The use of wide-screen and color. The conviction with which he made it. He was serious. And he created an atmosphere. We could see that he was going for something new.”

U.S. poster for Teenage Doll (1957), directed by Roger Corman. Look at the bare lightbulb; it’s like something from the cover of a hardboiled Mickey Spillane novel. Now look at the blood-red lips of that teenage doll with her eyes closed and a hint of bra strap playing peekaboo with … you. Is she dead, or has she just been ravaged? Corman knows, but he isn’t saying. And if you want to find out, you’ll have to pony up for a ticket.

U.S. poster for Machine-Gun Kelly (1958), directed by Roger Corman. A pre-fame Charles Bronson (née Charles Dennis Buchinsky) goes on a bullet-riddled B-movie bender.

Attack of the Crab Monsters 1957

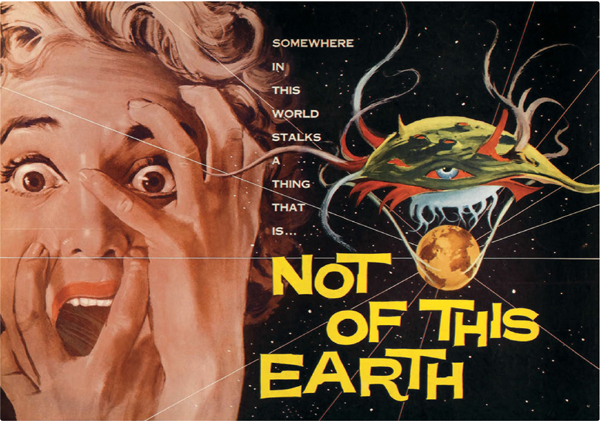

In 1957, Roger Corman directed nine movies. Shot on the cheap and usually cranked out in ten caffeinated days, Corman’s output during that Eisenhower-era annus mirabilis included such drive-in diversions as Rock All Night, The Undead, and The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent. All of these films (well, most of them at least) have their merits. But there’s one that stands out for its willingness to grapple with weightier questions than the fates of bobbysoxers and bargain-basement bogeymen—the luridly titled Attack of the Crab Monsters. Distributed by the Poverty Row studio Allied Artists, Crab Monsters was released on February 10, 1957, as part of a Corman sci-fi double bill alongside Not of This Earth. Taken together, these two cautionary tales form the backbone of Corman’s early obsession with the apocalyptic power of the A-bomb and the hubris of well-meaning scientists who, a short decade earlier, had unleashed a new form of wrath on the world in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Production shot from the set of Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957). Pamela Duncan practices running in terror, lest she become the next entrée in Corman’s seafood smorgasbord.

Written by Charles B. Griffith, who would go on to pen several other Corman classics like 1960’s The Little Shop of Horrors and 1975’s Death Race 2000, the $70,000 Crab Monsters kicks off with a crew of scientists arriving by seaplane on an unnamed deserted island in the South Pacific. They’re there to find out what happened to a previous research team that went missing. Could it have something to do with the fact that the island is smack dab in the middle of a nuclear testing zone? Before they have a chance to find out, things go disastrously wrong: One of the seamen bringing them ashore by raft falls overboard, only to resurface missing his head. Then, as the seaplane lifts off to return to the mainland, it explodes in midair. The table is set.

The team of stranded brainiacs include Dale Drewer (Richard Garland in an ascot), Martha Hunter (Pamela Duncan, wearing more makeup and tighter sweaters than one might expect in the jungle), and Hank Chapman (a pre–Gilligan’s Island Russell Johnson). Soon, they discover a journal filled with ominous entries of distress and hear the mysterious disembodied voices of the dead summoning them to the island’s caves, where they finally come face-to-face with … huge, radioactive, papier-mâché crustaceans with claws operated by piano wire able to absorb the thoughts of any human brain they nosh on! At one point, a crab monster telepathically warns: “So, you have wounded me! I must grow a new claw, well and good! For I can do it in a day! But will you grow new legs when I have taken yours from you?”

As the victims of this atomic retribution start to pile up, Corman’s chilling allegory of nuclear folly becomes a briskly paced meditation on our most destructive impulses. We’ve played God and must now pay for our sins. In more ways than one, Attack of the Crab Monsters is a B movie with bite.

U.S. poster for Stakeout on Dope Street (1958), directed by Irvin Kershner. The stark and controversial film was financed by Corman and future Oscar-winning cinematographer Haskell Wexler, who remembers using porno movie sets for the low-budget film because they were cheap to rent.

Production shot from the set of the gangster film Machine-Gun Kelly (1958), directed by Roger Corman. Corman rehearses a scene with female lead Susan Cabot. French critics were quick to recognize her brooding, granite-faced costar, Charles Bronson. He would soon become one of the globe’s most iconic action heroes—another Corman alumnus who graduated to bigger and better things.

ROGER CORMAN: “To my surprise, the French New Wave critics picked up on a little ten-day picture I did in 1958, Machine-Gun Kelly, starring an unknown actor named Charles Bronson. They gave it very good reviews. And they started to review my films without my knowledge because I wasn’t reading French magazines and newspapers.”

HASKELL WEXLER (cinematographer; post-Corman credits include In the Heat of the Night, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest): “I started my career as a cameraman on a TV show called Confidential File with the director Irvin Kershner. And after a while I told him I wanted to get into feature films. He had a script for a crime drama that I liked called Stakeout on Dope Street, and I agreed to put up half the money to make the film. I put up $15,000, and Roger Corman put up the other $15,000. I liked him immediately, but mostly because he was putting up half the money. We shot in this place where they shot some porno films. And when the union rep came by I would have to hide behind the scenery because I wasn’t in the union and I wasn’t supposed to be making the film. Roger managed to sell Stakeout on Dope Street to Warner Bros. for $75,000 or $80,000—a big profit.”

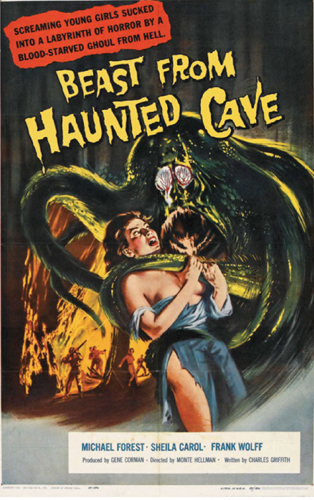

MONTE HELLMAN: “I first met Roger through my wife, Barboura Morris, who had acted in some of his movies. I got him to invest $1,000 in a theater company that we put together. Eventually, we were shut down, and Roger said, ‘You should take this as a sign to do something else.’ He hired me on the spot to direct Beast from Haunted Cave. He paid me $1,000. We didn’t have a contract or anything. Just a handshake. And Roger’s handshake was better than most people’s contracts. Roger’s brother, Gene, produced the film. Gene’s a lot of fun. A good guy. Not quite as tightfisted as Roger—but almost. We shot it in South Dakota, and it was below zero. I think we had Velveeta sandwiches for lunch every day on the set. Pretty luxurious. Velveeta sandwiches and a cup of hot chocolate. That was a big deal.”

Production still from The Last Woman on Earth (1960), directed by Roger Corman. Antony Carbone, Robert Towne, and Betsy Jones-Moreland are two guys and a girl staring down the end of the world. Towne, who acted in and wrote the film, quickly realized that his future was behind a typewriter rather than in front of a camera.

ROBERT TOWNE: “Roger said to me, ‘I want you to write a script with the title The Last Woman on Earth.’ That’s the amount of instruction I was given. Nothing about the plot or anything else. That’s it. Mercifully, I can’t remember what I wrote. We went down to Puerto Rico and shot it in six weeks. I was living in a rented house there with Roger, and I remember when I first got there, I went to take a shower, and there was Roger with a wet towel whacking hundreds of silverfish that were in the shower, trying to clean it out for me. Roger is nothing if not a gentleman. Then he got me to act in another movie called Creature from the Haunted Sea. I didn’t really see myself as an actor. And that movie confirmed my suspicions. It underlined that I most definitely did not have a career as an actor. And I was beginning to wonder if I had a career as a writer, too.”

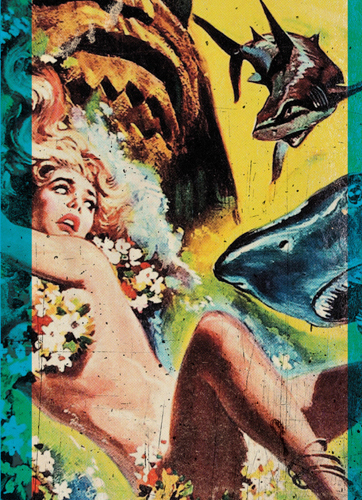

U.S. poster for She Gods of Shark Reef (1958), directed by Roger Corman. Menacing tiki idols, bloodthirsty great whites, and a bevy of pearl-diving beauties with discreetly placed leis. Corman knew how to get young moviegoers to part with their hard-earned cash—even if, as in the case of this lightweight Hawaiian lark, the film didn’t quite live up to the action-packed one-sheet.

U.S. poster for Beast from Haunted Cave (1959), directed by Monte Hellman. Corman tapped his friend Hellman to direct this subzero monster mash, paying him the royal sum of $1,000. Hellman would prove to be more of an auteur than his silly debut for Corman suggested. His existential road movie, 1971’s Two-Lane Blacktop, remains one of the great films of the New Hollywood generation.

U.S. poster for Not of This Earth (1957), directed by Roger Corman. Corman directed nine films in 1957. This sci-fi flick, about aliens hungry for human blood to send back to their home planet Davana, was one of the best … and most confusing. Martin Scorsese remembers seeing the movie as a kid and being confounded by its logic, but he admits he was hooked nonetheless. Little did Scorsese know that a decade and a half later he’d be on a Corman set, directing a movie of his own.

U.S. poster for Teenage Caveman (1958), directed by Roger Corman. The original title for this sci-fi timewarp was Prehistoric World. But after scoring at the box office with I Was a Teenage Werewolf and I Was a Teenage Frankenstein, AIP changed the title. Robert Vaughn, who would later star in The Magnificent Seven and The Man from U.N.C.L.E., plays a primitive man who discovers that his Stone Age world is actually a post-apocalyptic future.

Frame grabs from Creature from the Haunted Sea (1961), directed by Roger Corman. A lovers’ kiss is interrupted by one of the worst-looking (or greatest, depending on your sweet tooth for schlock) monsters in movie history.

ROGER CORMAN: “AIP developed a sales strategy to send out two ten-day black-and-white pictures together as a double bill, with the idea that you would get two pictures for the price of one—two horror films, two science fiction films, or two gangster films. It was successful, but I could see—because I had a percentage of the profits—that the sales gimmick was starting to fade a little bit. They were still profitable, but they were making less money, I could see the peak of the cycle had hit and it was starting to turn down. I explained my interpretation of what was going on to Sam Arkoff and Jim Nicholson. I said, ‘What I’d really like to do is make one fifteen-day horror film in color that could be sold on its own.’ They asked me what I wanted to make, and I said The Fall of the House of Usher. I had no thought of doing a series of Poe films, I just wanted to do Usher. And one of the executives at AIP said, ‘But there’s no monster in the house!’ I had to think fast, and I said, ‘The house is the monster.’ And they said OK. I had read The Fall of the House of Usher in school, and I asked my parents for the complete works of Edgar Allan Poe for Christmas. They were delighted to give it to me because I could have asked for a shotgun or who-knows-what. And I read all of Poe’s stories. That was the picture that really jumped AIP.”

RICHARD MATHESON (writer of several of Corman’s Poe films; author of I Am Legend): “I was writing for The Twilight Zone when I hooked up with Roger. He hired me to write four of the Poe films, beginning with House of Usher, which I was pleased with because I regarded it as a classic. Anyway, it seemed like a classy venture. I had to improvise more story, though, because in Poe’s story, there was no girl and no romance. I had to add all of that. I think it turned out quite well. Plus, I got the chance to meet Vincent Price—he was the nicest man I ever met in the business.”

U.S. poster for The Brain Eaters (1958), directed by Bruno VeSota. Another Corman sci-fi quickie. Sharp-eyed audiences may spot a young Leonard Nimoy.

ROGER CORMAN: “I sent Vincent the script for House of Usher through his agent. And he read it and said he’d like to meet with me. We talked about the picture and my ideas about how to do it, and he told me his thoughts. We got along very well together, and he agreed to make the film. And the way we worked on the Poe pictures was we would discuss the film in advance and talk about his character and his motivations, because even with fifteen days, I did not have time to stop and have long character analyses with the actors on the set. So when we shot it, it required just a little bit of discussion before each scene because we’d already done the work. And Vincent took it very seriously. He didn’t think that he was dropping down in the caliber of films he was starring in. They were good parts. He took every film very seriously.”

Still from It Conquered the World (1956), directed by Roger Corman. Beverly Garland tries to hide (good luck in that sweater!) from a foam-rubber Venusian beastie. Yes, the monster looks like an angry pickle. But the film, clocking in at a svelte sixty-eight minutes, flies by.

RICHARD MATHESON: I went to the set of Usher. It was gorgeous—[production designer] Danny Haller really did a wonderful job on all of those pictures, especially with how little they had. Roger was such a quick and efficient director. When he finished a shot, he would always say, ‘We’re on the wrong set!’ Meaning, let’s move onto the next shot right away. And Roger’s boss at AIP, Sam Arkoff, he was cheap! When he would come back from lunch, he would buy a stick of gum and bill it to the budget of whatever film he was making. I don’t think AIP or even Roger expected House of Usher to do as well as it did. It ran on double bills with Psycho all summer and made a lot of money. Next thing you know, AIP wanted more Poe movies fast.”

JOHN SAYLES (writer, director; post-Corman credits include Matewan, Eight Men Out, and Lone Star): “By the late fifties, there was a little Roger Corman cult in Europe. But no one here reviewed the movies he directed. The Poe movies, beginning with House of Usher, really had style and a sense of humor. Roger knew his movies were going to play to teenagers. Teenagers are into rebellion, so anything that’s transgressive they’re going to eat up. And his movies really move! If you just look at them with the sound off, which is what I often tell film students to do, they really are very, very efficient—especially a movie like Little Shop of Horrors, where he was taking advantage of a set he had for two days!”

ROGER CORMAN: “There have been a lot of stories about Little Shop of Horrors being shot in two and a half days and starting as a bet. But it was really just sort of a joking thing on my part. I was having lunch with the head of a small rental studio in Hollywood where I had my office, and he mentioned that they had a rather nice set built for some picture that was finished, and nobody was coming in and it was just sitting there. And I just had the idea: I could go in and shoot for the fun of it. I had an idea that horror could be combined with comedy in a new way. And I thought, I’ll give it a try on a two-day schedule and half a night. There was a night of exterior shooting as well. So the studio manager laughed and said, ‘Sure, if you want to rent it for two days, I’ll give you a deal.’ So I did it as a joke. And a friend of mine bet me that I couldn’t do it. One of the reasons the picture was successful, I think, is because Charles Griffith’s script was funny. But also everybody took it as kind of a joke. So everybody was laughing and making up lines. I’ve always felt that the spirit of the cast and the crew affects the picture. And I think that helped the picture—the fact that we all took it in a joking sort of a way.”

U.S. poster from House of Usher (1960), directed by Roger Corman. As a boy, Corman devoured Edgar Allan Poe’s tales of terror and never shook them from his nightmares. By 1960, he had already directed more than twenty movies at a furious clip. It was time to slow down and make something … important. So Corman returned to his youth for a series of big-screen Poe adaptations with his partner in the danse macabre, Vincent Price. The Poe films would make movie lovers and critics reconsider Corman as a filmmaker. Maybe there was more on his mind than cheap thrills.

Frame grab from House of Usher (1960). Vincent Price senses something sinister in the air as the accursed Roderick Usher.

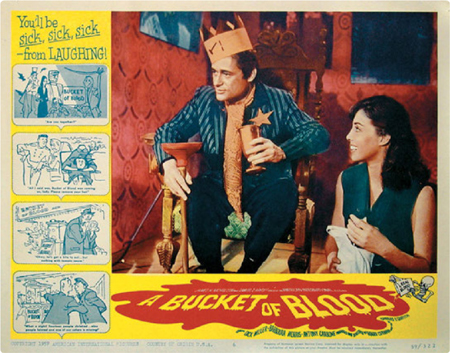

DICK MILLER: “I was supposed to play the lead in Little Shop of Horrors, and like an idiot, I read it and said, ‘This is like A Bucket of Blood,’ which I had just been in. I didn’t think of it as a step up furthering my career. Now, I could kick myself! You think back on all the things you’ve turned down and then said, ‘Oh, God … .’ It turns out to be a big hit. You win some, you lose some. I never thought the idea to shoot it so quickly was insane. If Roger said he was going to make the picture in two and a half days, then he was going to make it in two and a half days.”

JONATHAN HAZE: “I liked Little Shop of Horrors, of course, because it made me pretty famous. He was a good director based on the fact that he made his movies cheap and fast and that kids wanted to see them. It was the height of the drive-in era, and he made movies that were good double-feature movies. Jack Nicholson didn’t work that long on Little Shop—he worked part of a day, I think. I had known Jack—he was a regular at Schwab’s Drug Store where a lot of actors hung out. Jack was a good actor and studying with a good teacher at the time. And he got good breaks after that, so he didn’t stay being a Corman actor. I stayed being a Corman actor, which was kind of like having a disease as far as anyone else wanting to be around you. If you had done a lot of Corman movies and you went on an interview at MGM, they held it against you.”

Frame grab from The Little Shop of Horrors (1960), directed by Roger Corman. Screenwriter Charles B. Griffith makes a cameo as a thief who messes with the wrong plant.

JACK NICHOLSON: “I wasn’t exactly Roger’s favorite leading man because other guys were doing movies that—how do I put this?—came out better. So Roger thought of me for the wilder things. But I knew that this was very funny. He knew I wanted it, and he said, ‘Well, I can’t keep you from reading it.’ … I went into the shoot knowing I had to be very quirky because Roger originally hadn’t wanted me. In other words, I couldn’t play it straight. So I just did a lot of weird shit that I thought would make it funny. … Jonathan Haze was up on my chest pulling my teeth out. And in the take, he leaned back and hit the rented dental machinery with the back of his leg, and it started to tip over. Roger didn’t even call ‘Cut.’ He leapt onto the set, grabbed the tilting machine, and said, ‘Next set, that’s a wrap.’ I went to the opening of Little Shop at the Pix, at Sunset and Gower. It was, oddly, a full theater. I had had a horrible experience at the opening of Cry Baby Killer because the audience just went absolutely berserk. So I was a bit nervous going in there. I took a date. And when my sequence came up, the audience went absolutely berserk again. They laughed so hard I could barely hear the dialogue. I didn’t quite register it right. It was as if I had forgotten it was a comedy since the shoot. I got all embarrassed because I’d never really had such a positive response before.”

Lobby card from A Bucket of Blood (1959), directed by Roger Corman. Corman perennial Dick Miller stars in this dark comedy about a failed artist who finally finds success when he kills a cat and covers it with plaster. To keep up with his newfound fame, he has to find other subjects to kill and turn into sculptures. Miller was offered the lead in Corman’s follow-up, The Little Shop of Horrors, but passed because he thought the two films were too similar. Says Miller, “Now, I could kick myself!”

MARTIN SCORSESE: “Little Shop of Horrors, which is a movie that’s beyond tongue in cheek, is a film that totally enjoys itself, and the audience is in on the gag. And part of the gag is that it was made in three days! Now, whether you like the films or not, he proved that a film can get made in three days! Which, when you think about it, is really quite amazing.”

Frame grab from The Little Shop of Horrors (1960). Jonathan Haze, Mel Welles, and Jackie Joseph behold the flesh-eating flower, Audrey. “Feeeed meeee!”

Lobby card from The Little Shop of Horrors (1960). Jonathan Haze and Jackie Joseph share a sweet moment between bouts of man-eating mayhem.

Lobby card from The Little Shop of Horrors (1960). Jonathan Haze’s lonely nebbish, Seymour Krelboyne, watches helplessly as things get out of hand in the flower shop.

The Little Shop of Horrors 1960

Over the past fifty years, the legend behind the making of The Little Shop of Horrors has eclipsed the film itself. Which is a shame, because it remains one of the most subversive movies that Roger Corman ever made. Initially conceived as a quickie follow-up to 1959’s more straight-faced A Bucket of Blood, Little Shop sprang to life when Corman was offered the free use of an existing office set for a single weekend. That’s all he would need—he shot the entire film in two days and a night. Corman has called the bruise-black comedy (originally titled The Passionate People Eater) “an experiment in just how cheaply a film could be made.” And by any motionpicture metric, that experiment was a triumph. Little Shop cost a mere $28,000, thanks to the round-the-clock efforts of his bleary-eyed crew and tireless turns from his stock company of players (Jonathan Haze, Mel Welles, Dick Miller, and a young Jack Nicholson). If anything, the movie’s madcap pace behind the scenes helps rather than hurts the movie—it gives Little Shop its dizzy, fizzy kick.

Jonathan Haze stars as Seymour Krelboyne, a meek nebbish who works in a Skid Row floral shop run by a blustery blowhard named Gravis Mushnik (Mel Welles). Seymour is a perpetual victim—his overbearing, bedridden mother (Myrtle Vail) smothers him with a laundry list of daily demands, his boss belittles him, and his beautifully ditzy coworker Audrey (Jackie Joseph) winds him into a constant state of pent-up sexual frustration. Seymour is a little man—a neutered mama’s boy being pulled at from every direction. Something’s gotta give.

Then, one day, Seymour breeds a strange new plant in an attempt to lure customers into the failing floral shop. It looks like a Venus flytrap, and he christens it Audrey Jr., after his secret love. But soon she, like all of the other people in his life, wants something. And what Audrey Jr. wants is human flesh. As the plant begins to wilt, she cries out, “Feeed meeee!” Seymour has no choice but to find fresh victims to fill her carnivorous maw and sate her appetite. Beat cops, dentists, prostitutes, no one is spared from the tongue-in-cheek feeding frenzy when Audrey needs Freudian nourishment. In a minor but marvelous role, Jack Nicholson virtually leaps off the screen and into your lap as a cackling, masochistic dental patient named Wilbur Force. The actor, who got his first big break in Corman’s 1958 film The Cry Baby Killer, provides one of Little Shop’s most memorable gags after he refuses Novocaine (“It dulls the senses”) and finds ecstasy on the business end of a dentist’s drill: “Oh my God, don’t stop now!!!”

Little Shop was only a modest hit when it was released. But it wouldn’t take long for its mad streak of merry-prankster mayhem to earn cult status with a generation of hip college students looking for rebellion on the big screen. By the end of the decade, New Hollywood directors like Mike Nichols (The Graduate), Arthur Penn (Bonnie and Clyde), and Dennis Hopper (Easy Rider) would bring this same sentiment to mainstream moviegoers. But, as ever, Corman was there first.